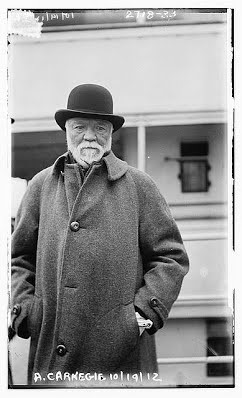

“There is not such a cradle of democracy upon this earth as the free public library.” -Andrew Carnegie

One of my favorite parts of my job as a regional coordinator at the Indiana State Library is traveling around to the public libraries of Northwest Indiana. Though I value and appreciate each and every unique library, Carnegie libraries have always been my favorite. It is for this reason that I chose to research Carnegie libraries of Indiana as one of my projects for my library master’s program. I hope you’ll appreciate the interesting history which I discovered during my research.

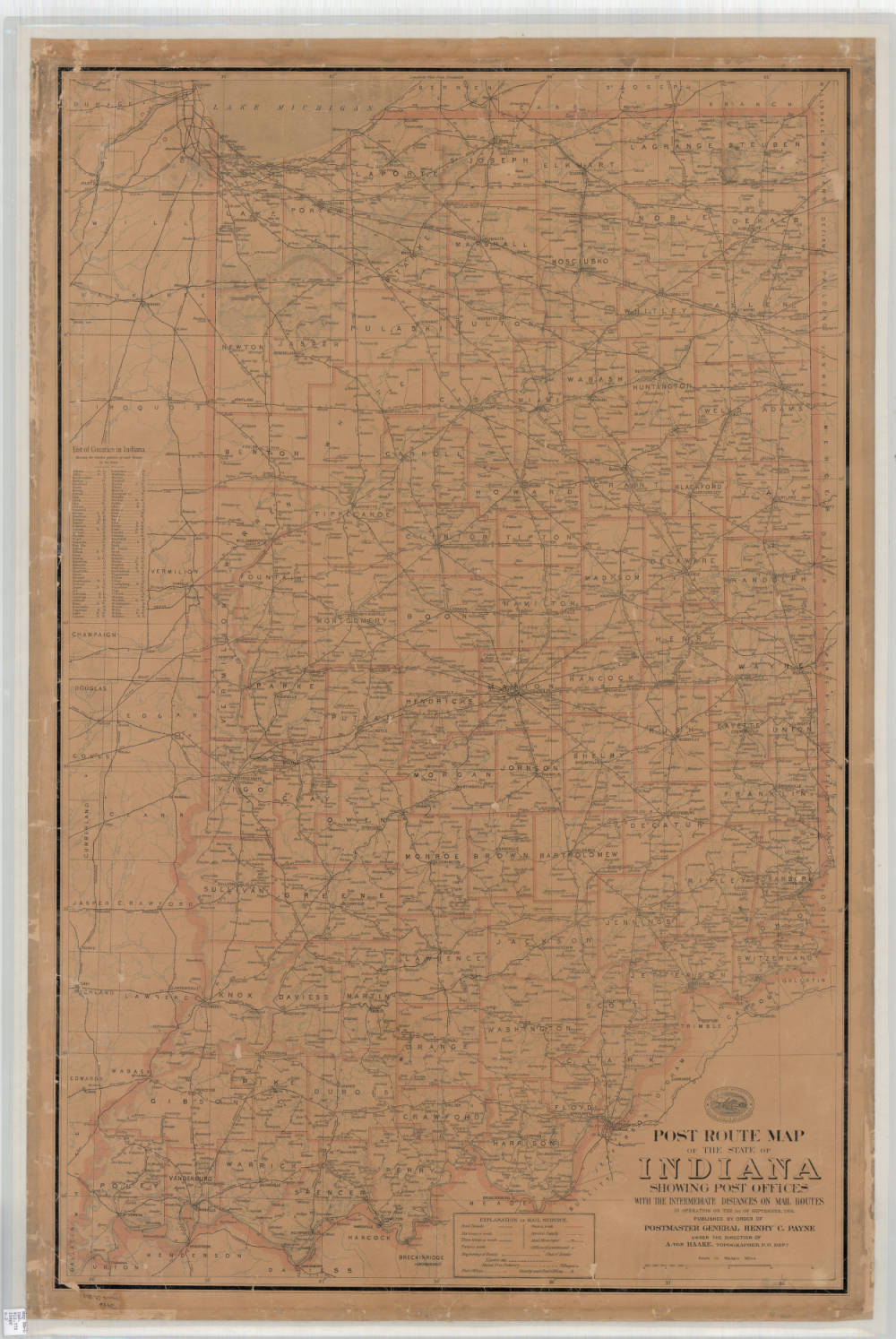

The state of Indiana received the greatest number of Carnegie library grants of any state. Between the years of 1901 to 1918, Indiana received a total of 156 Carnegie library grants, which allowed for the creation of 165 library buildings. Indiana received a total of over $2.6 million from the Carnegie Corporation. These library buildings were constructed from 1901 to 1922. Goshen received the first grant in 1901, and Lowell received the final grant in 1918. Additionally, Indiana was provided two academic libraries funded by Carnegie, at DePauw and Earlham. Indiana also has their own “Carnegie Hall” located at Moores Hill College. The Carnegie grants received by Indiana ranged in size from $5,000 given to Monterey – a community of under 1,000 residents – to $100,000 given to Indianapolis to construct five library branches. The year that the most Indiana Carnegie grants were given was 1913, wherein 19 grants totaling $202,500 were awarded. One thing Indiana can be proud of is that none of the communities receiving a Carnegie grant defaulted on their pledge to provide for the library building once it was initially constructed.

Goshen Carnegie Library sign. Courtesy of Groundspeak, Inc.

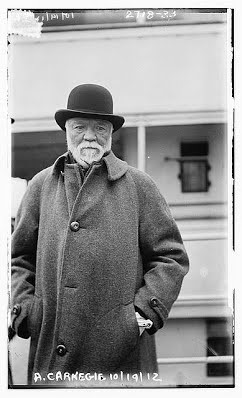

“A. Carnegie.” 19 October 1912. Bain News Service. Courtesy of Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Prior to receiving grants from Andrew Carnegie, the public-funded township and county libraries in Indiana were “limited in literary selection, poorly housed and often meagerly staffed.” However, libraries were in high demand by literate, reading Hoosiers. The only public book collections in the state before 1880 were William Maclure funded Mechanic and Workingmen’s Libraries, and most Indiana counties had one. William Maclure was the first library philanthropist in Indiana, providing for 146 libraries in 89 counties by the year 1855. However, it is believed that without Andrew Carnegie’s philanthropy, many of the smaller Indiana communities would have experienced long delays in establishing public libraries, or not even have had a public library at all. Andrew Carnegie was invited to many of the library building dedications in the state of Indiana, but he never attended any. Carnegie’s library grants ended the day that the United States entered World War I, on Nov. 7, 1917. The last Carnegie building to be completed in the state of Indiana was in 1922 at North Judson.

While researching this topic, I came to wonder why the state of Indiana had so many Carnegie grants; more than any other state. Part of the reason is due to the variations in branch donations. Many communities, including Indianapolis, Gary, East Chicago and Evansville, received grants to divide up among multiple branches. Also, once Goshen received the first library grant – and the General Assembly passed the Mummert Library Law which permitted “local units of government to levy tax for the perpetuation and maintenance of all libraries built in Indiana by Mr. Carnegie” – other Indiana communities were able to secure Carnegie grants, while meeting Mr. Carnegie’s stipulations, with not as much tedious effort as Goshen. As more and more communities received Carnegie grants and constructed public library buildings, neighboring towns would take notice and then start the application process for their own Carnegie library grant. From the time period of 1900 to 1929, “a strong public library fervor rolled across Indiana.” At this time, Indiana became “culturally ready and geographically positioned for more libraries.” The Indiana Library Association began in 1891. Later, in 1899, a legislative act permitted towns to levy taxes for library purposes and also established the Public Library Commission. The Public Library Commission, in operation from 1899 to 1925, was paramount in assisting Indiana communities to apply for and secure library funding from Andrew Carnegie during what was known as the Carnegie Era. McPherson writes that “libraries were landmarks of public and private achievement and pride.” Hoosiers especially cherished libraries as “intellectual and democratic institutions that were ‘free to all.'” Women’s literary clubs also played an invaluable role in the amount of Carnegie libraries established in Indiana.

Very few of the towns requesting grants from Andrew Carnegie were refused, as long as they agreed to his terms. However, there were still some Carnegie grant requests that were denied, and usually for administrative reasons. For example, Greenfield requested a Carnegie grant and received a response from James Bertam, Andrew Carnegie’s private secretary, stating that “A request for $30,000 to erect a library building for 5,000 people is so preposterous that Mr. Carnegie cannot give it any consideration.

Most of the Carnegie funded libraries were designed to have a community meeting space on the main floor and the library’s book collection on the upper floor. In 1908, the Carnegie Corporation circulated a pamphlet called “Notes on the Erection of Library Buildings,” which standardized the design of Carnegie buildings “in order to prevent costly design errors.” Therefore, prior to 1908 when library boards had more leeway on building design and spending, “the more grandiose and elegant building were constructed.” Carnegie emphasized simplicity, functionality and practicality in order “to reduce wasteful spending of the earlier years” and in turn had the final sign-off on any architectural plans. An Indianapolis architect, Wilson B. Parker, designed over 20 of the Carnegie funded libraries in Indiana, more than any architect of Carnegie libraries in the state. The most widely used architectural styles of the Indiana Carnegie library buildings were the Neoclassic Greek and Roman style and the Craftsman-Prairie Tradition style. The buildings were normally constructed along or near the main street of town, where community members were likely to gather. Intentionally built with steps, Carnegie libraries encouraged “patrons to ‘step up’ intellectually when they walked up the main entryway, entering ‘higher ground’ through the temple like portal into the rooms of knowledge.” Once a Carnegie building was completed, the community would hold a dedication, especially around a holiday. Many of Indiana’s Carnegie library buildings have been added to The National Register of Historic Places, as well as the Indiana State Register of Historic Sites and Structures.

Corydon Carnegie Library, 2006. Courtesy of Indiana Landmarks. Accessed through Indiana Memory Database.

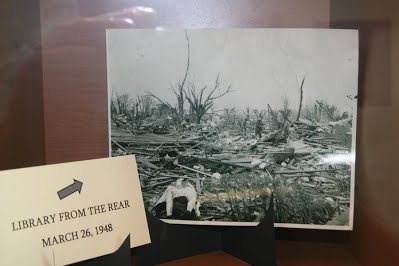

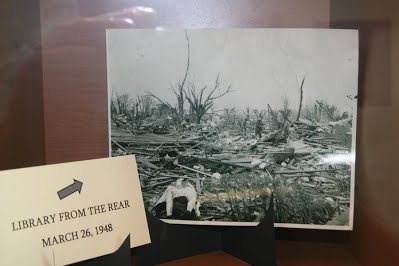

As a strong testament to the lasting legacy of Andrew Carnegie, 100 of the original 164 buildings are still in use as libraries today. Many have been renovated or have additions, but continue to serve the community out of at least some part of or all of the original Carnegie funded library building. The buildings not currently serving as libraries have a wide array of purposes, including two restaurants, six town or city halls, museums, three historical societies, four art galleries, condos, a police station, a fraternity headquarters, courthouse, a church, private residences and various commercial offices such as real estate, law and an architectural firm. Sadly, 18 of the original Carnegie library buildings in Indiana have been destroyed through the years; one by the tornado of 1948, three by fire and the rest demolished or razed. Click here to see a list of Indiana’s Carnegie libraries and their current status.

Coatesville Library Destruction from 1948 Tornado. Courtesy of Coatesville-Clay Township Public Library.

Woody’s Library Restaurant, present day. Courtesy of Woody’s Library Restaurant.

Sources

McPherson, Alan. “Temples of Knowledge: Andrew Carnegie’s Gift To Indiana.” Indiana: Hoosier’s Nest Press, 2003.

“Goshen Public Library Beginnings,” retrieved form the Goshen Public Library website.

Bobinski, George S. “Carnegie Libraries: Their History and Impact on American Public Library Development”. ALA Bulletin, 62.11 (1968):1361-1367.

“Carnegies 2009 Update.” Indiana State Library. 6 June 2012.

Indiana’s Carnegie Libraries website, created by Laura Jones.

Submitted by Laura Jones, Northwest regional coordinator, Indiana State Library.