Image traveling through a forest so thick that you could do it without ever touching the ground. You could go from tree limb to tree limb, with very little visible grass or flowers, just climbing along. Now imagine this area being Indianapolis, circa 1780. Up until around 1820, the area we now know as the capitol of Indiana was exactly that, a massive dense forest. Settlers then moved in, cleared land, began farms and started to form a community.

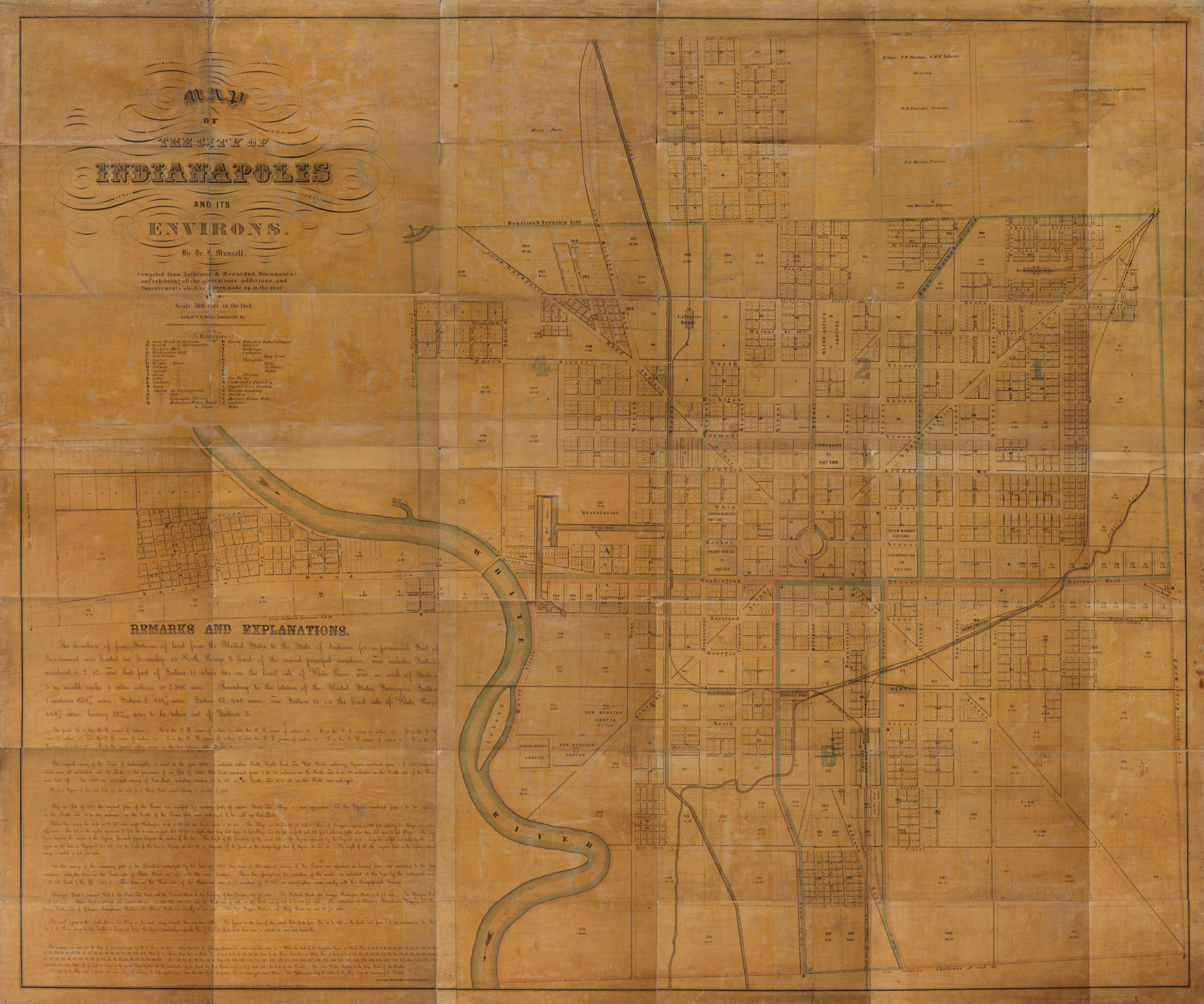

Several maps of early Indianapolis show the layout of the mile square, but it wasn’t until 1852 that we saw the first map of the city with any detail.

When we first got this map out and saw exactly what we had to deal with, we knew it wasn’t going to be an easy task to digitize it. In fact, the two pictures below show what the book looked like. It had been dissected, glued onto linen and folded to fit on the shelf, which was a very common library practice early on. Nowadays, we don’t do that.

Rebecca, our conservator, painstakingly took pictures of each section, then recreated the completed image that you now see in our digital collections. This was a several day process. Now this extremely rare map has come back together and we can study it and learn what the layout of the city was like in the early 1850s.

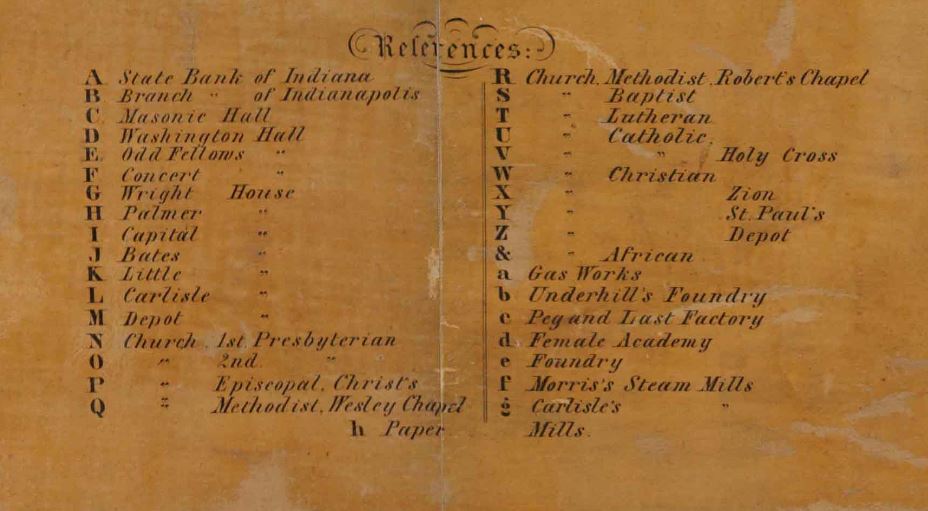

For example, the railroad lines and their depots beeline the map, showing how the trains moved merchandise, goods and passengers in all directions. Passengers might have seen a map like this hanging at the train station. Checking the legend, they could have found several houses for accommodations, such as The Palmer House (H) or The Bates House (J), both at the corners of Illinois and Washington Streets, just a few blocks up from the station. After getting settled in, they might have walked up to the governor’s residence to pay a call on Joseph Wright, Indiana’s governor in 1852.

The map also shows the small portion of the massive 296-mile planned canal system and its path through the city; only eight miles of the canal were completed. Beginning at the White River, the canal ran east, then headed north and south. The canal helped facilitate interstate commerce and also provided alternative transportation for passengers.

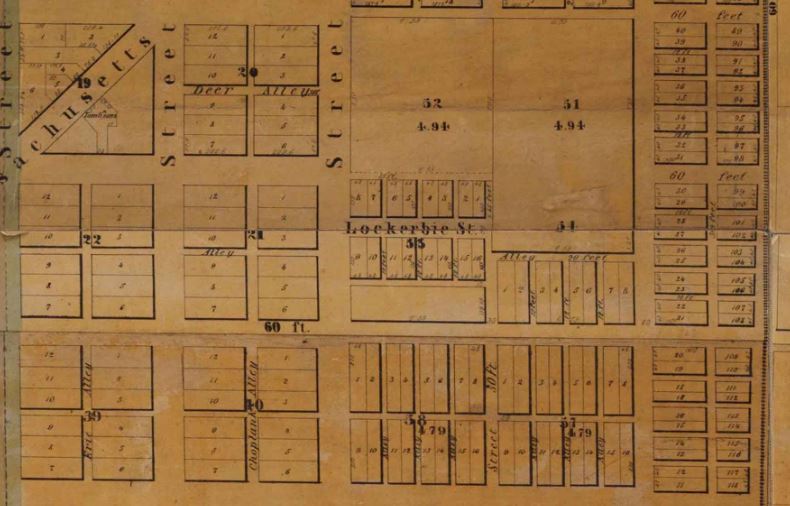

Most of the transportation routes, such as the canals and railroads, are south of the residential areas, including the current Lockerbie Square and the old Northside neighborhoods. Oftentimes, residential areas grew north of the industrial areas as winds would blow the smoke and pollution south.

Later maps, such as those published in 1855 and 1866, show fewer details. Both maps can be viewed on the Library of Congress’s website. We have the maps at the state library, but the Library of Congress has done such a great job digitizing their copies that we just refer researchers to those digitized maps. Our copies, sadly, are in need of much repair.

This post was written by Chris Marshall, digital collections coordinator for the Indiana Division at the Indiana State Library.