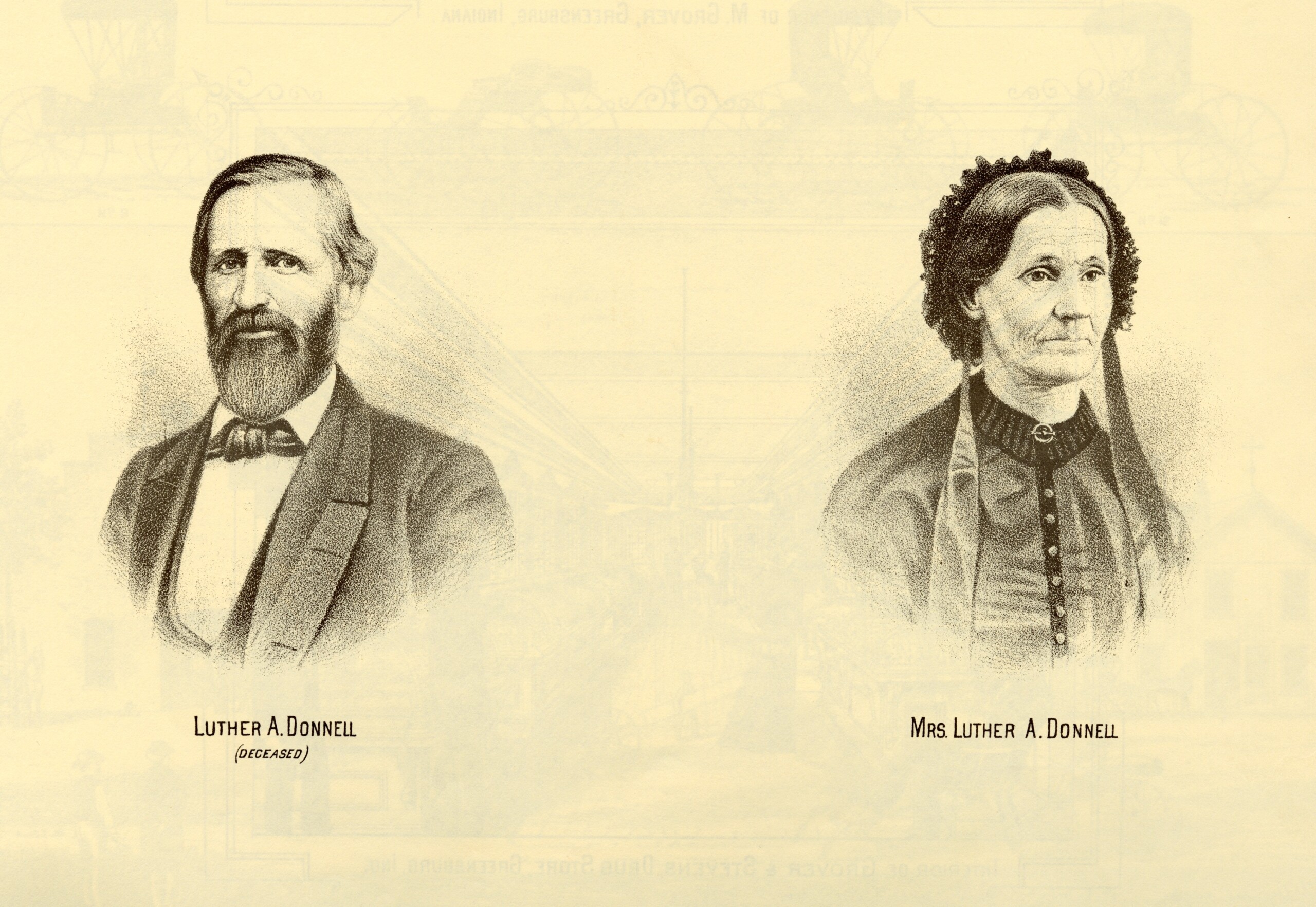

Luther Addison Donnell was born July 6, 1809 in Nicholas County, Kentucky. His father, Thomas Donnell and uncle, Samuel Donnell, were involved in the Kentucky Abolitionist Society at its onset. By 1823, the Donnells and other abolitionists had moved to Decatur County, Indiana. In 1836, Luther Donnell established the Decatur County Anti-Slavery Society and helped found the Indiana Anti-Slavery Society in 1838.

Donnell aided a woman – identified in court documents as Caroline, but who later changed her name to Rachel Beach – and her four children in their flight from enslavement. They escaped Oct. 31, 1847, from Trimble County, Kentucky and were in Decatur County the next day when they were assisted by Donnell and other residents. After crossing the Ohio River into Madison, Indiana, they were transported by a man named Waggoner to Douglas McCoy at McCoy’s Station before attempting to make it to Clarksburg under the cover of night. The woman and her children were housed with Jane Speed, a black woman who unfortunately lived near a refuted “slave-hunter,” Woodson Clark, who spied Speed’s son delivering food to the family in an un-used building on the property. Clark lured and entrapped Caroline into a building on his son’s property, insisting that she was unsafe and with promises to deliver her to the African American settlement near Clarksburg. African American residents who had been expecting the family, tracked them to the home of Woodson Clark and enlisted the assistance of Donnell to reunite and free the family. Mr. Donnell and a Mr. Hamilton applied for a writ of habeas corpus to search Clark’s property for the detained woman. Not finding her on Clark’s property, the search was extended to include the property of his sons. Caroline, bewildered and searching for her children, was found on one of the sons’ farms. George Ray and several slave-hunters appeared in town with their own writ allowing them to search for the family, however they had been hidden in a deep ravine. The usual route of the Underground Railroad from that point had recently been discovered and in order to evade the men hunting for her, she was disguised as a man and separated from her children, who were couriered on to the next point. Donnell, Hamilton and several other local men then escorted the family via carriage to William Beard’s home in Union County, Indiana. According to Canadian census records and a reference to a letter made by Hamilton, the family did make it across the Detroit River to Ontario, Canada.

Donnell aided a woman – identified in court documents as Caroline, but who later changed her name to Rachel Beach – and her four children in their flight from enslavement. They escaped Oct. 31, 1847, from Trimble County, Kentucky and were in Decatur County the next day when they were assisted by Donnell and other residents. After crossing the Ohio River into Madison, Indiana, they were transported by a man named Waggoner to Douglas McCoy at McCoy’s Station before attempting to make it to Clarksburg under the cover of night. The woman and her children were housed with Jane Speed, a black woman who unfortunately lived near a refuted “slave-hunter,” Woodson Clark, who spied Speed’s son delivering food to the family in an un-used building on the property. Clark lured and entrapped Caroline into a building on his son’s property, insisting that she was unsafe and with promises to deliver her to the African American settlement near Clarksburg. African American residents who had been expecting the family, tracked them to the home of Woodson Clark and enlisted the assistance of Donnell to reunite and free the family. Mr. Donnell and a Mr. Hamilton applied for a writ of habeas corpus to search Clark’s property for the detained woman. Not finding her on Clark’s property, the search was extended to include the property of his sons. Caroline, bewildered and searching for her children, was found on one of the sons’ farms. George Ray and several slave-hunters appeared in town with their own writ allowing them to search for the family, however they had been hidden in a deep ravine. The usual route of the Underground Railroad from that point had recently been discovered and in order to evade the men hunting for her, she was disguised as a man and separated from her children, who were couriered on to the next point. Donnell, Hamilton and several other local men then escorted the family via carriage to William Beard’s home in Union County, Indiana. According to Canadian census records and a reference to a letter made by Hamilton, the family did make it across the Detroit River to Ontario, Canada.

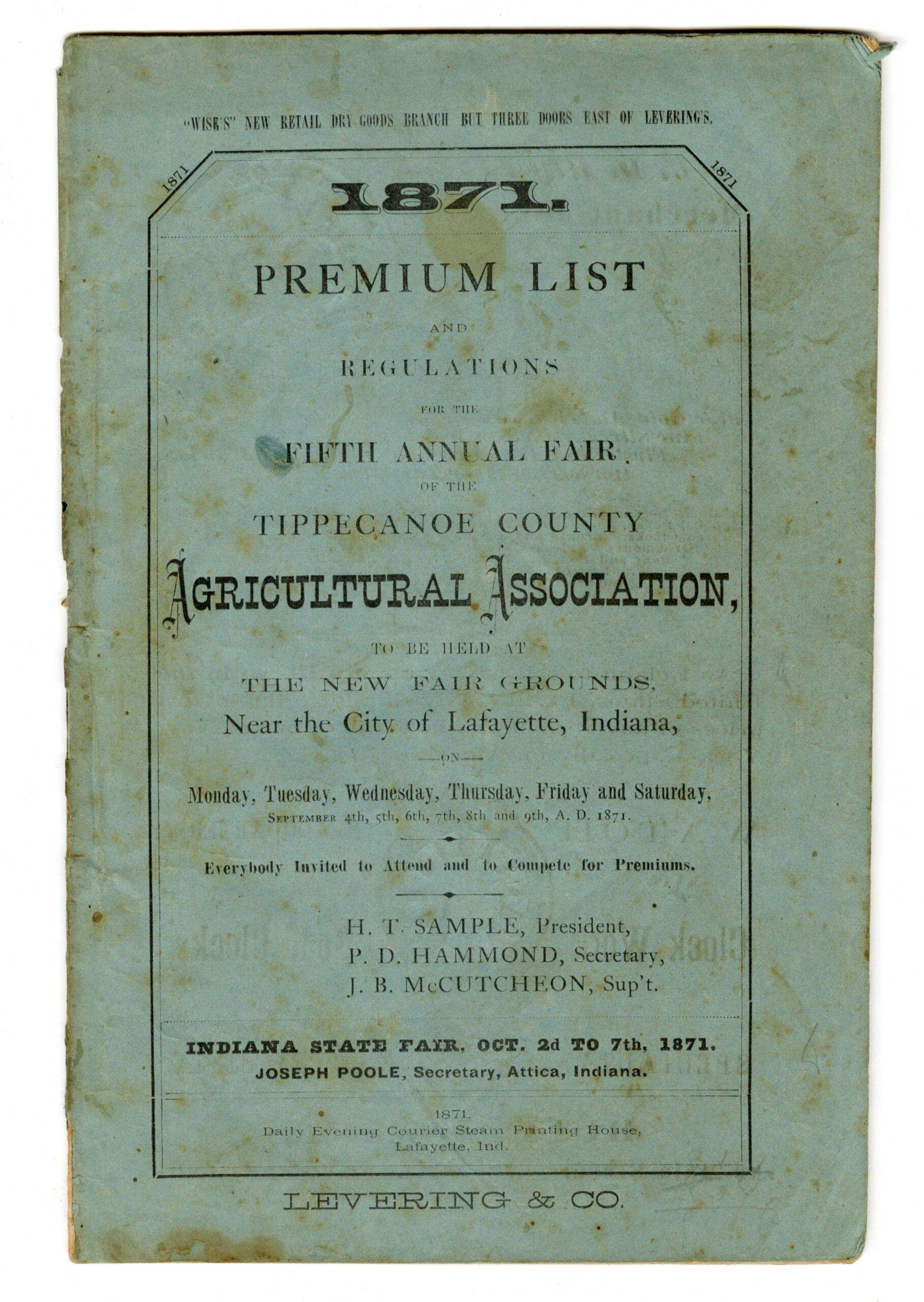

Donnell was convicted in 1849 in Decatur Circuit Court of aiding fugitive slaves. The document in the Indiana State Library’s collection is an early 1848 affidavit which identifies only Amanda, one of Caroline’s daughters. George Ray also filed a civil suit against Donnell for the “value of his property” and received a judgment of $3,000 including court costs. In 1852, Donnell’s appeal went to the Indiana Supreme Court and he was a defendant in State of Indiana v. Luther A. Donnell which overturned the verdict against him based on the unconstitutionality of the earlier law.

This blog post was written by Lauren Patton, Rare Books and Manuscripts librarian, Indiana State Library. For more information, contact the Indiana State Library at 317-232-3678 or “Ask-A-Librarian.”

Related digital collections: https://indianamemory.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p16066coll31/id/2462/rec/3

https://indianamemory.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p1819coll6/id/81818/rec/2

Sources:

Luther A. Donnell court document, 1848. S3480. Indiana State Library, Manuscripts Division, Indianapolis, IN. 17 June 2024.

Atlas of Decatur Co. Indiana. Knightstown, Ind.: Decatur County Historical Society, Inc., 1976.

“State of Indiana v. Luther A. Donnell collection, 1848-1849.” University of Michigan William M. Clements Library. Accessed June 17, 2024. https://findingaids.lib.umich.edu/catalog/umich-wcl-M-7175sta.

“The Story of Luther Donnell.” Indiana Department of Natural Resources. Accessed June 17, 2024. https://www.in.gov/dnr/historic-preservation/files/donnell.pdf

“Escape of Caroline 1847.” Indiana Historical Bureau. Accessed June 17, 2024. https://www.in.gov/history/state-historical-markers/find-a-marker/escape-of-caroline-1847/

Eliason, Laura. “Luther A. Donnell court record.” Indiana State Library. Last modified October 7, 2021. https://archives.isl.lib.in.us/repositories/2/resources/6179

“Donnell v State 1852.” Indiana Historical Bureau. Accessed June 17, 2024. https://www.in.gov/history/state-historical-markers/find-a-marker/donnell-v-state-1852/