Dec. 7, 1941 is the day the Japanese military bombed Pearl Harbor. The event and America’s subsequent entry into World War II are a part of our history, but it is a history many only know from a high school class or from movies. The materials in our collection could be used to add depth to your knowledge of the day “that will live in infamy” or even change your understanding of it.

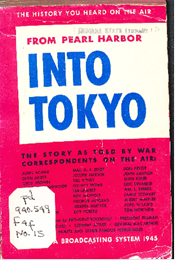

The Indiana State Library has over 200 items on Pearl Harbor in various formats throughout our collections. The Federal Government Documents Collection includes hearings and reports on, and by, the Pearl Harbor Survivors Association, as well as materials such as “Pearl Harbor revisited: United States Navy Communications Intelligence, 1924-1941” by Frederick D. Parker and the United States National Security Agency/Central Security Service Center for Cryptologic History, which is part of the United States Cryptologic History series. Of particular interest is the book “From Pearl Harbor Into Tokyo: the Story as told by War Correspondents on the Air.” Published in 1945, it is best described by the following information, which is on the title page:

“The documented broadcasts of the war in the Pacific as they were transmitted by CBS throughout America and the world, are taken verbatim from the records of the Columbia Broadcasting System.”

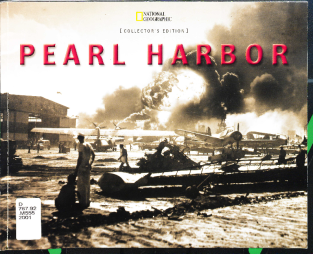

The library’s general collection has a wide variety of materials on Pearl Harbor written from different angles and viewpoints. These include the book “Remember Pearl Harbor” by Blake Clarke, published in 1942. This book has accounts of the attack in snippet style, firsthand viewpoints of military and civilians, that give the feel of what happened that day. There is also “Pearl Harbor,” a 2001 National Geographic Collector’s Edition book that along with quotes from survivors, has photographs of a time leading up to that day, the attack itself and its aftermath.

So, if you’re interested in “the date that will live in infamy,” according to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, or simply want to impress your teacher or professor with your next history project, come to the Indiana State Library and we’ll help get you the resources you need.

This blog post was written by Daina Bohr, Reference and Government Services librarian. For more information, contact the Reference and Government Services Division at (317) 232-3678 or via email.