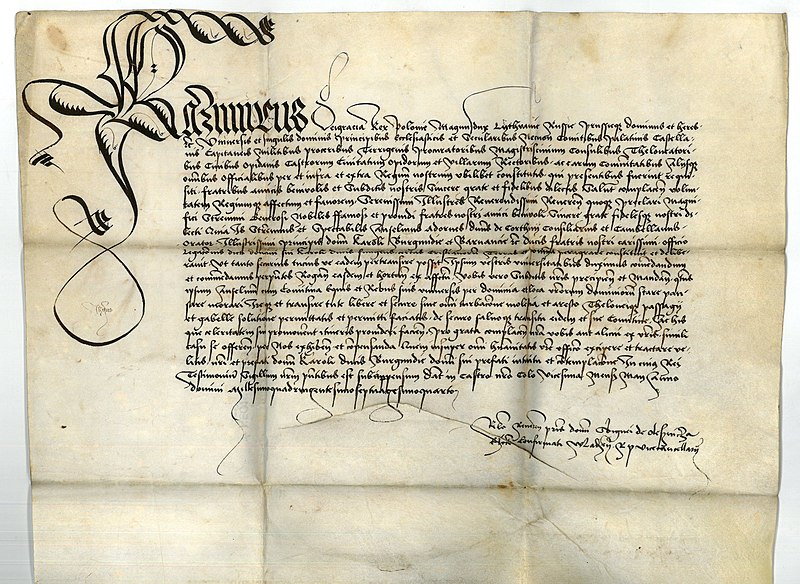

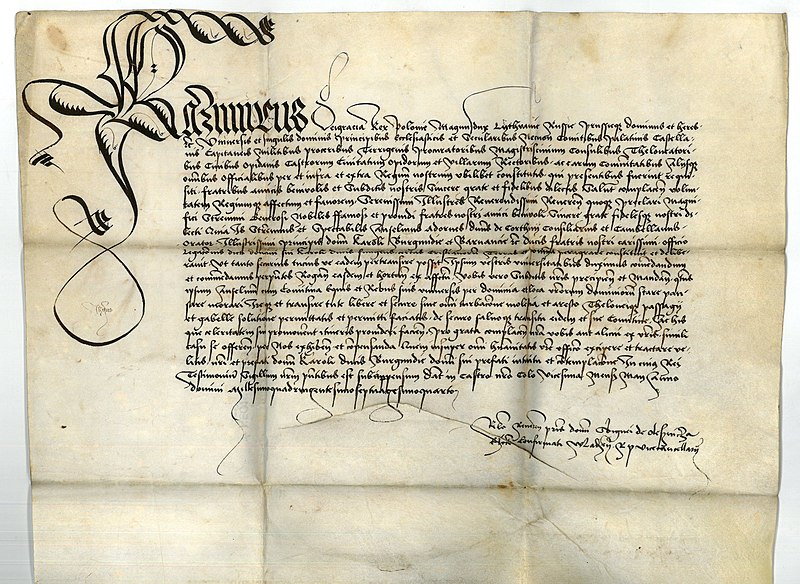

Durable passport books that can easily fit in a pocket are a relatively recent invention. Prior to the 20th century, travel papers were just that: letters or single-page documents from a monarch or government requesting safe passage for their citizens. These travel documents can be traced back millennia to about 450 B.C.E. in ancient Persia. Other early instances of such documentation have been found in India and China as early as the third century B.C.E. In the Middle Ages, travel documents for moving between regions within a country, or to visit colonies or foreign nations were issued in many places around the world, including the Islamic Caliphate, Italian city-states and England. An example of one such document is the secretarial letter of safe conduct issued in the name of King Casimir IV Jagiellon of Poland and given to Anselm Adornes, a merchant from Bruges acting as a diplomat for the Duke of Burgundy, on his way to Persia in the 15th century.

Anselm Adornes secretarial letter of safe conduct from King Casimir IV Jagiellon of Poland, ca. 1470. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

King Louis XIV of France popularized the modern use of passports – still a letter of request for safe passage – by providing a personally signed “passe port” to many of his court favorites. The English word “passport” derives from the French term meaning “to pass through a seaport,” harkening to the days when ship travel was the dominant means of journeying between countries. Most European states likewise developed systems to issue passports to their citizens and visas to visitors.

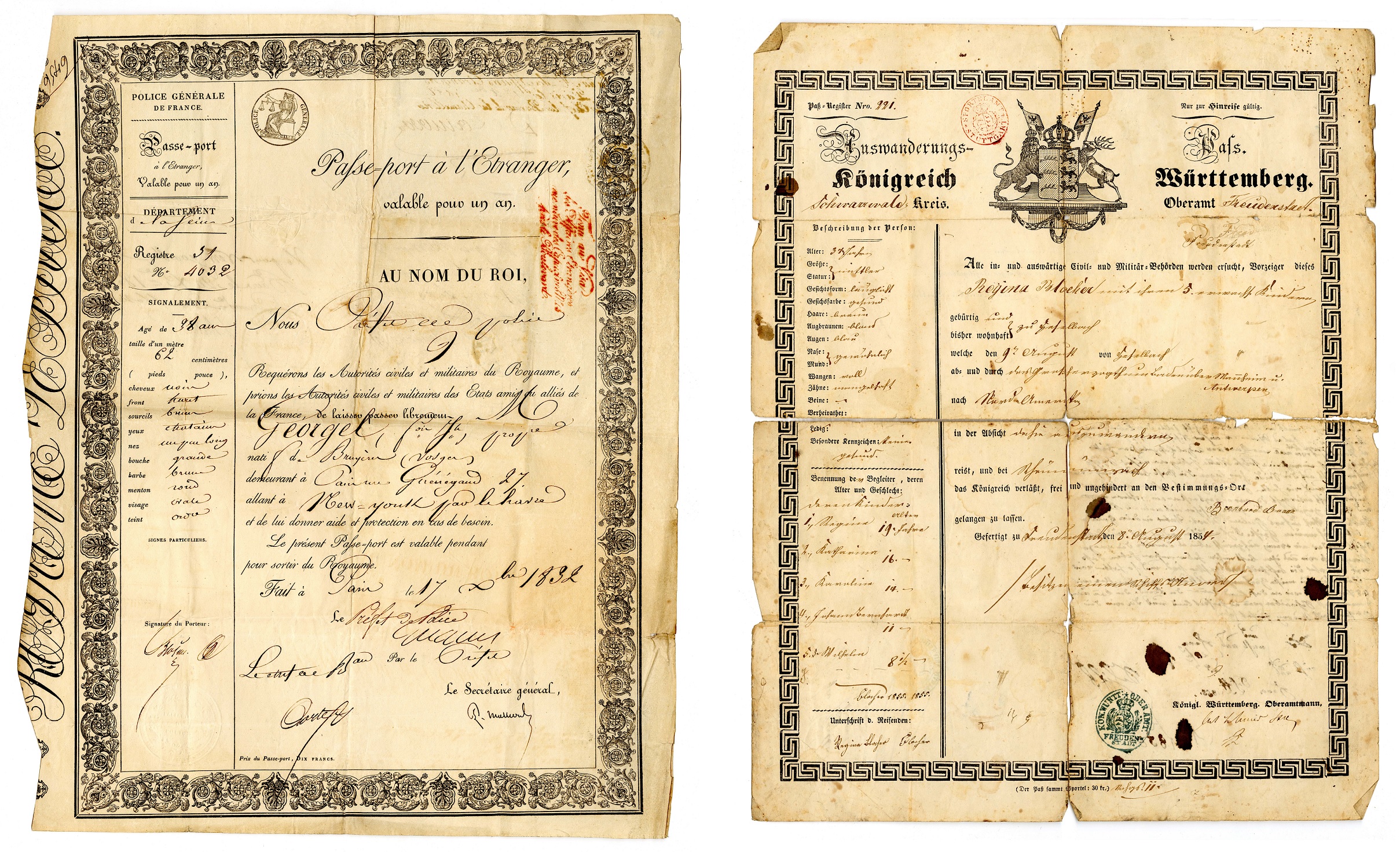

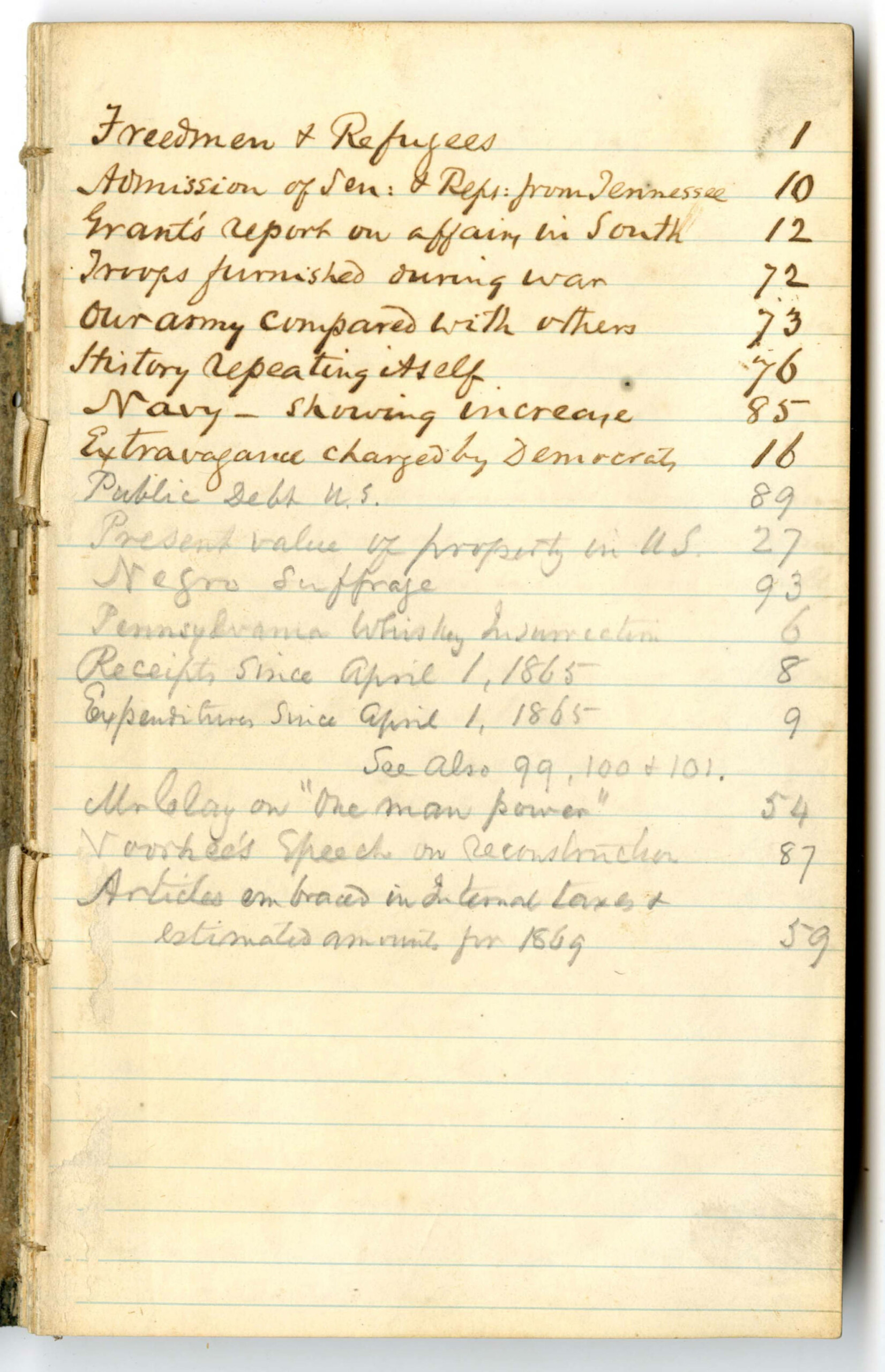

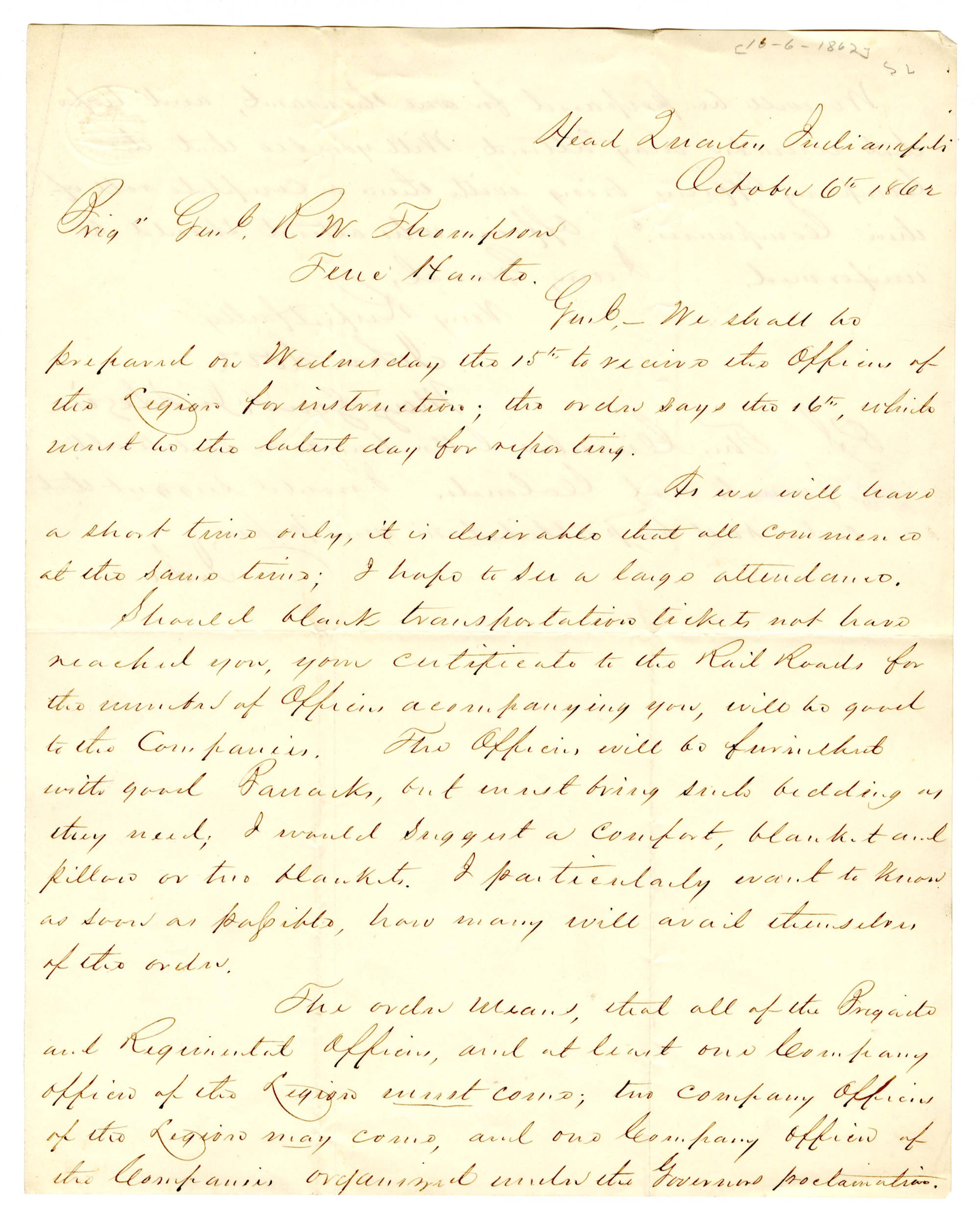

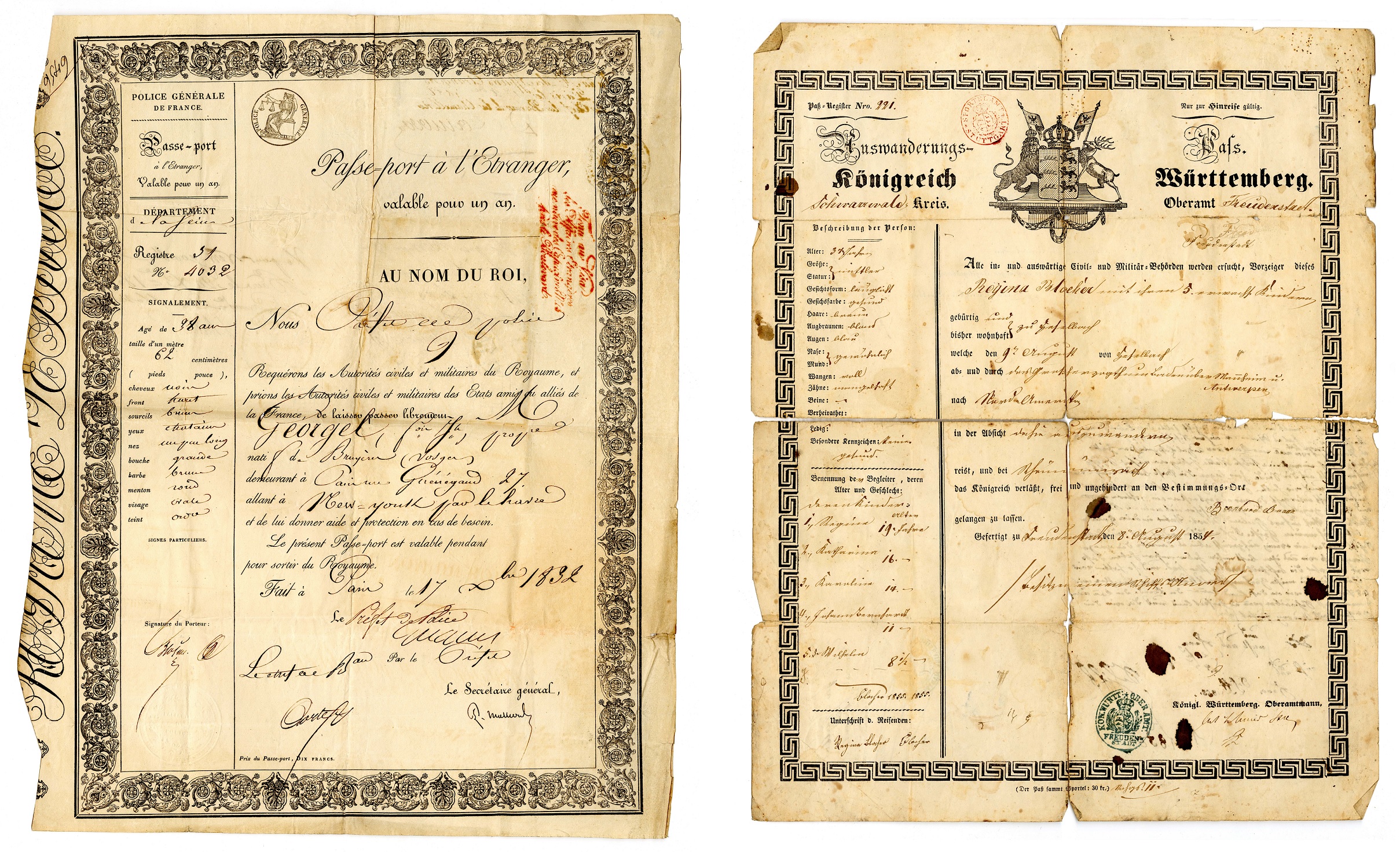

By the 19th century, passports in European countries had evolved from personally granted letters from monarchs into large, one-page documents issued by authorized government entities. In the United States, passports could be issued by states, cities and notaries public in addition to the Department of State until 1856, when the latter became the sole authority by an act of Congress.

19th century European passports, 1832, 1854. Sources: DuFour family papers (L046) and John B. Stoll collection (L149), Rare Books and Manuscripts, Indiana State Library.

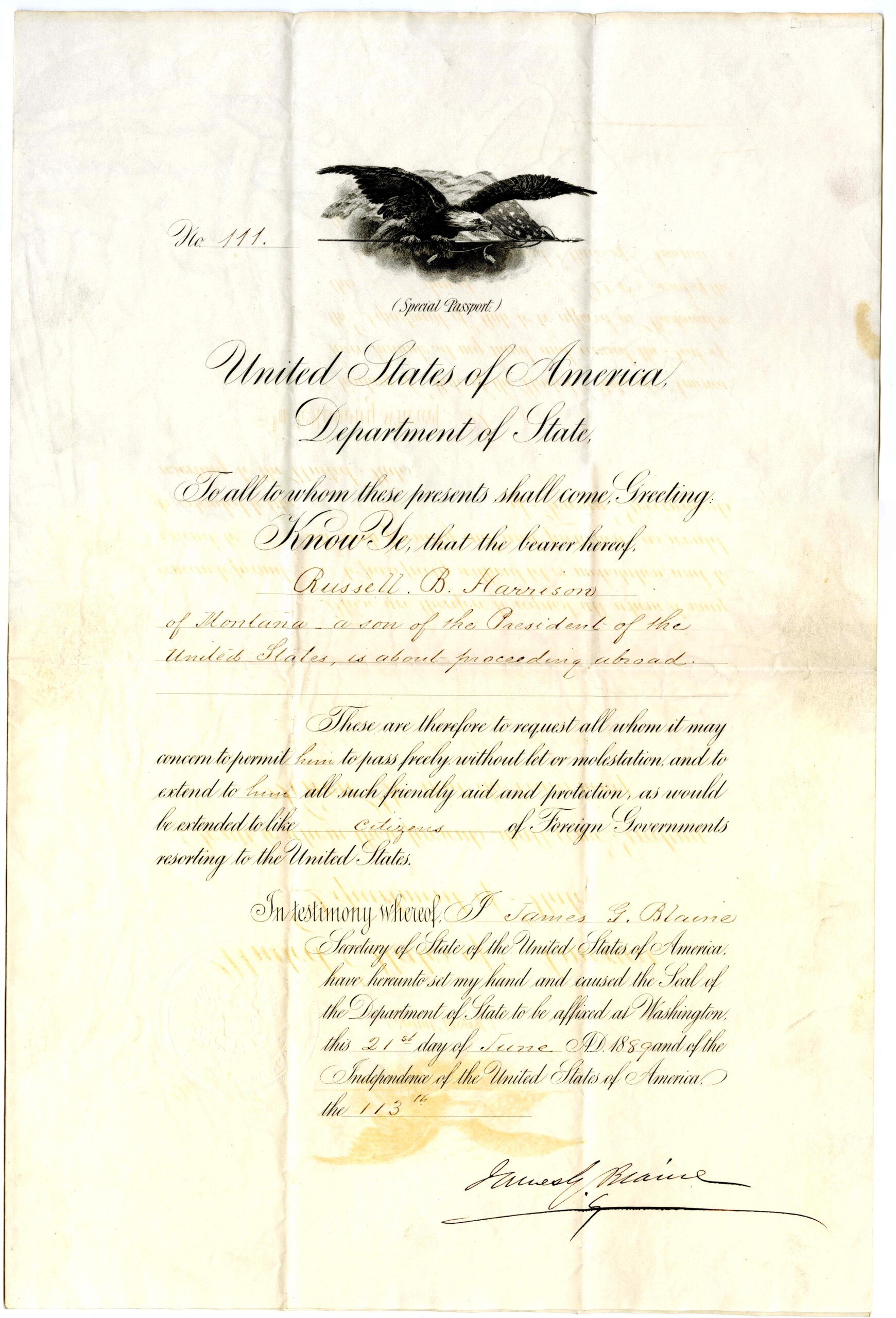

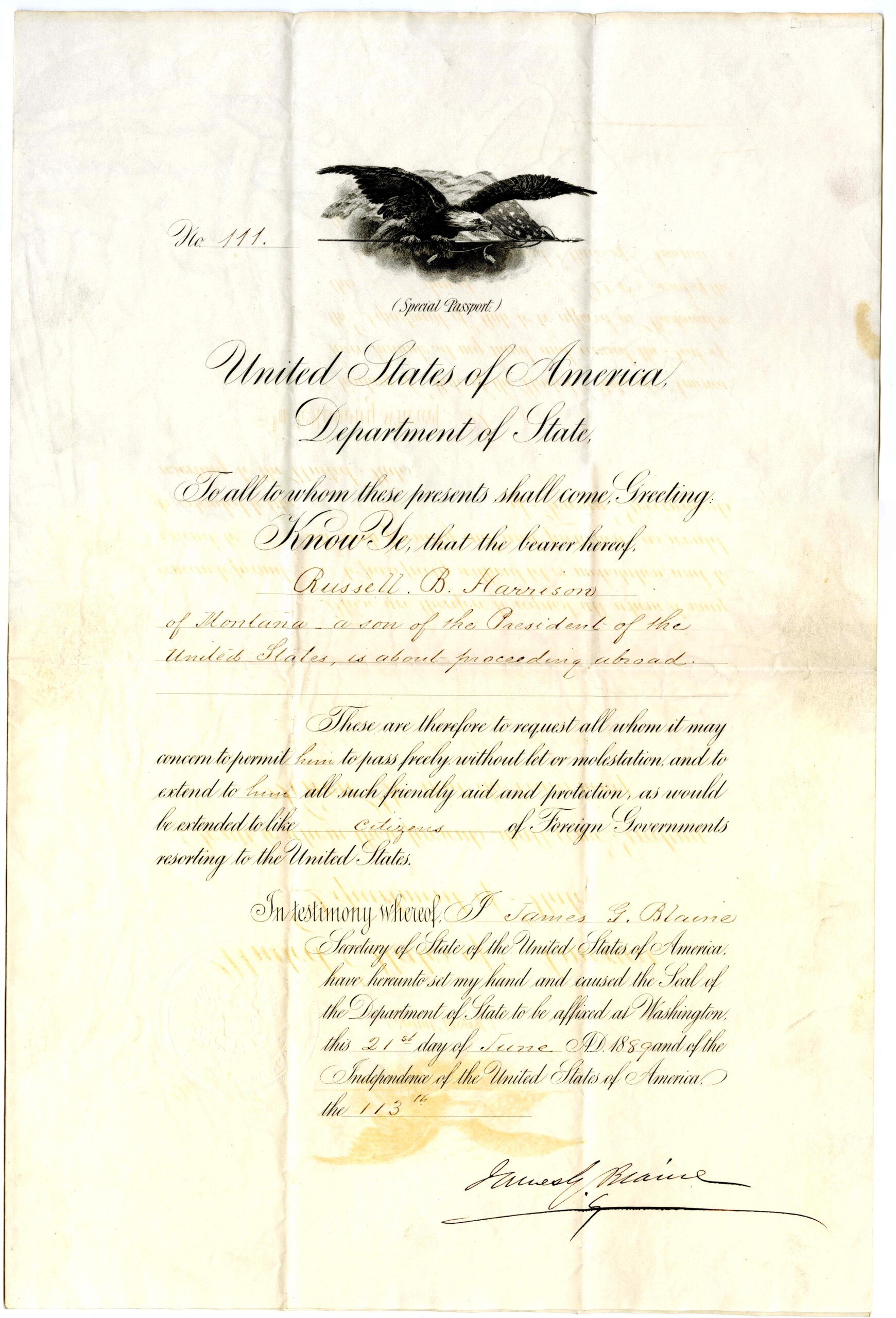

At that time, the United States and most European countries did not require their citizens to obtain passports to traverse national borders except in times of war. Passports were issued on an ad hoc basis – often to government officials, the wealthy and people of prominence – to smooth the way for their voyaging citizens, but they were not necessary or viewed as long-term forms of identification. The passport of Russell B. Harrison, the son of President Benjamin Harrison, is an example of simple travel papers supplied to someone with high connections. His passport has no identifying information save, “Russell B. Harrison of Montana, a son of the President of the United States, is about proceeding abroad.”

Russell B. Harrison passport, 1889. Source: Benjamin Harrison collection (L063), Rare Books and Manuscripts, Indiana State Library.

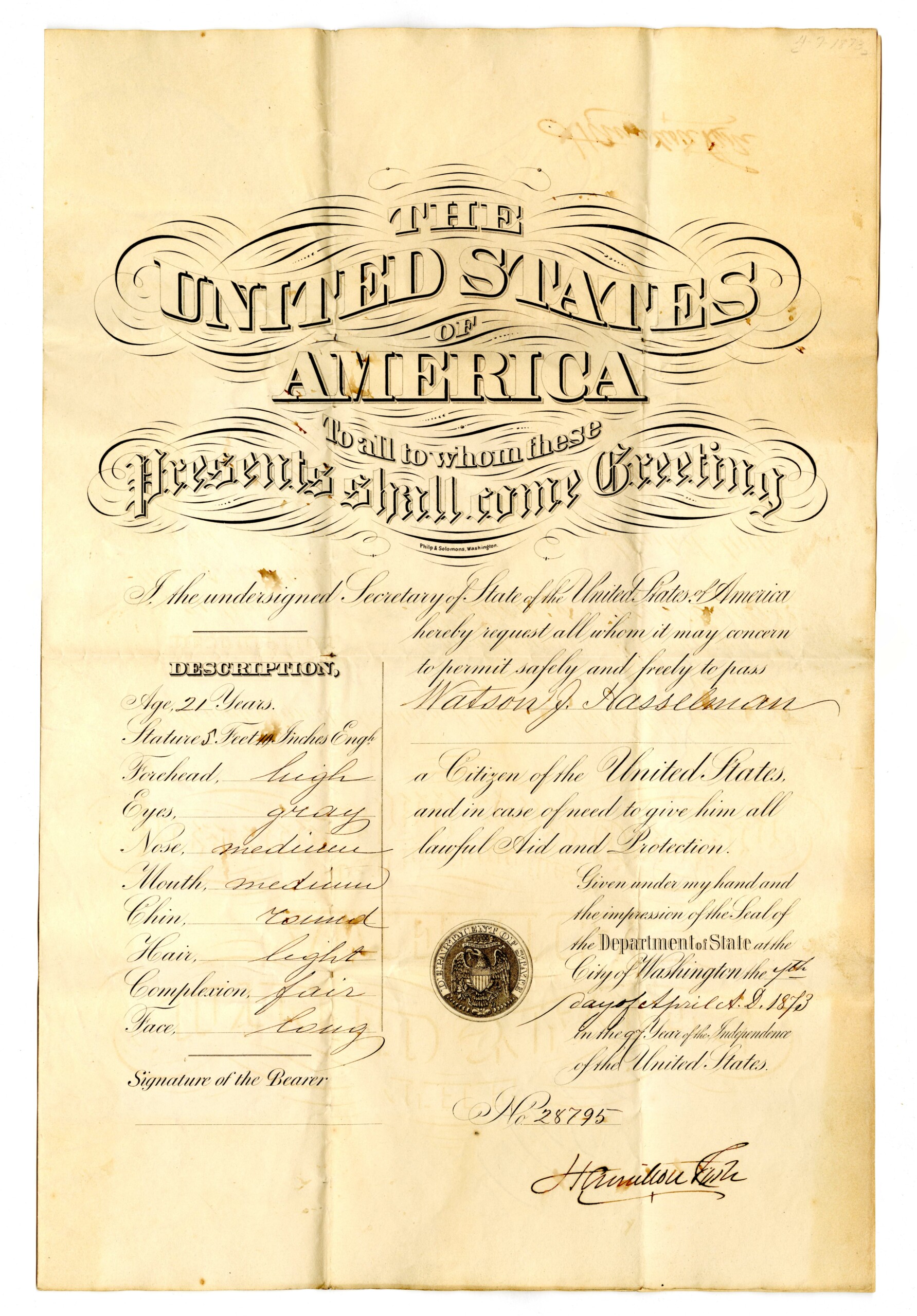

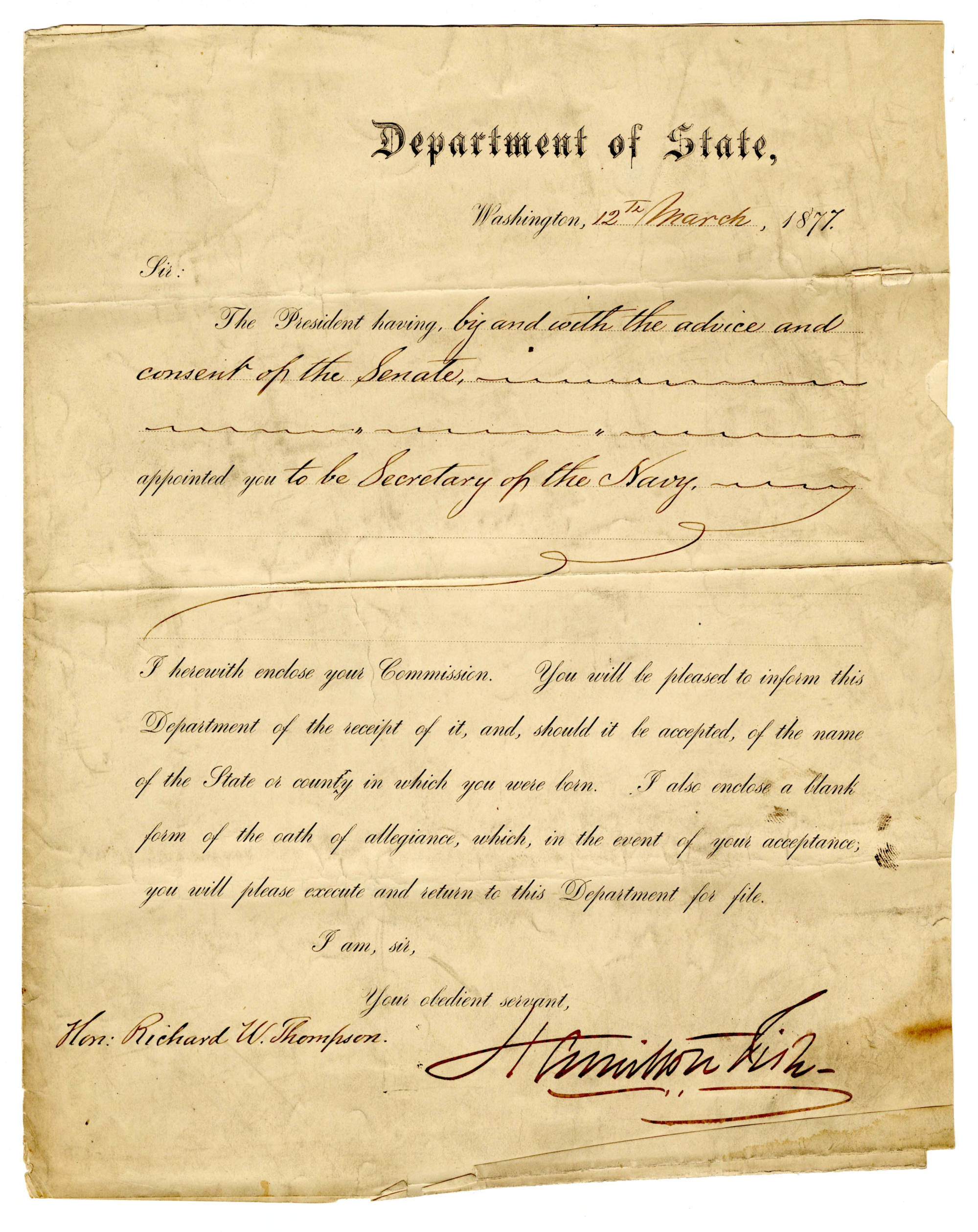

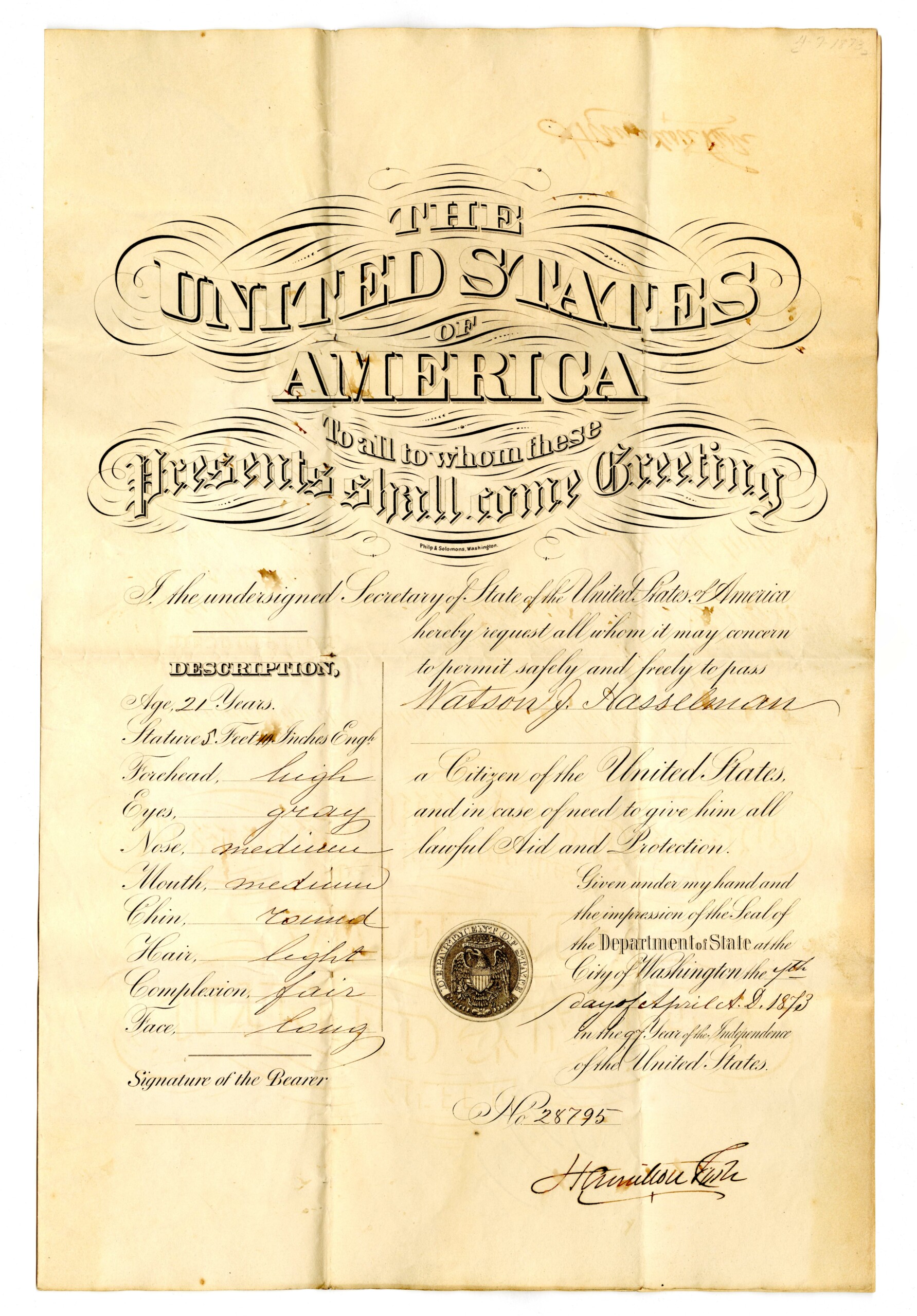

Nineteenth century Euro-American passports were typically a single-sided page with the name of the traveler, their country of origin, a signature from the issuing authority and the issue date, at minimum. They might also include where the holder intended to travel or their purpose in doing so. The papers were not intended for long-term use or identification and often only utilized for single trips. Over the next few decades, passports would often indicate expiration dates, usually six months to two years after issuance. Many passports also included the age and physical description of the document holder, as illustrated by Watson J. Hasselman’s passport from 1873. Photographs would not be utilized for identification on passports until 1914.

Watson J. Hasselman passport, 1873. Source: Hasselman and Blood family papers (L385), Rare Books and Manuscripts, Indiana State Library.

According to the National Archives, the U.S. State Department issued 130,360 passports between 1810 and 1873. The majority of those passports were issued to white men. After reviewing countless passports, archives specialist Rebecca Sharp of the National Archives only encountered two passports granted to free Black men before the U.S. Civil War. Her finding is unsurprising, since African Americans, free or enslaved, did not have indisputable citizenship until the ratification of the 14th Amendment in 1868.

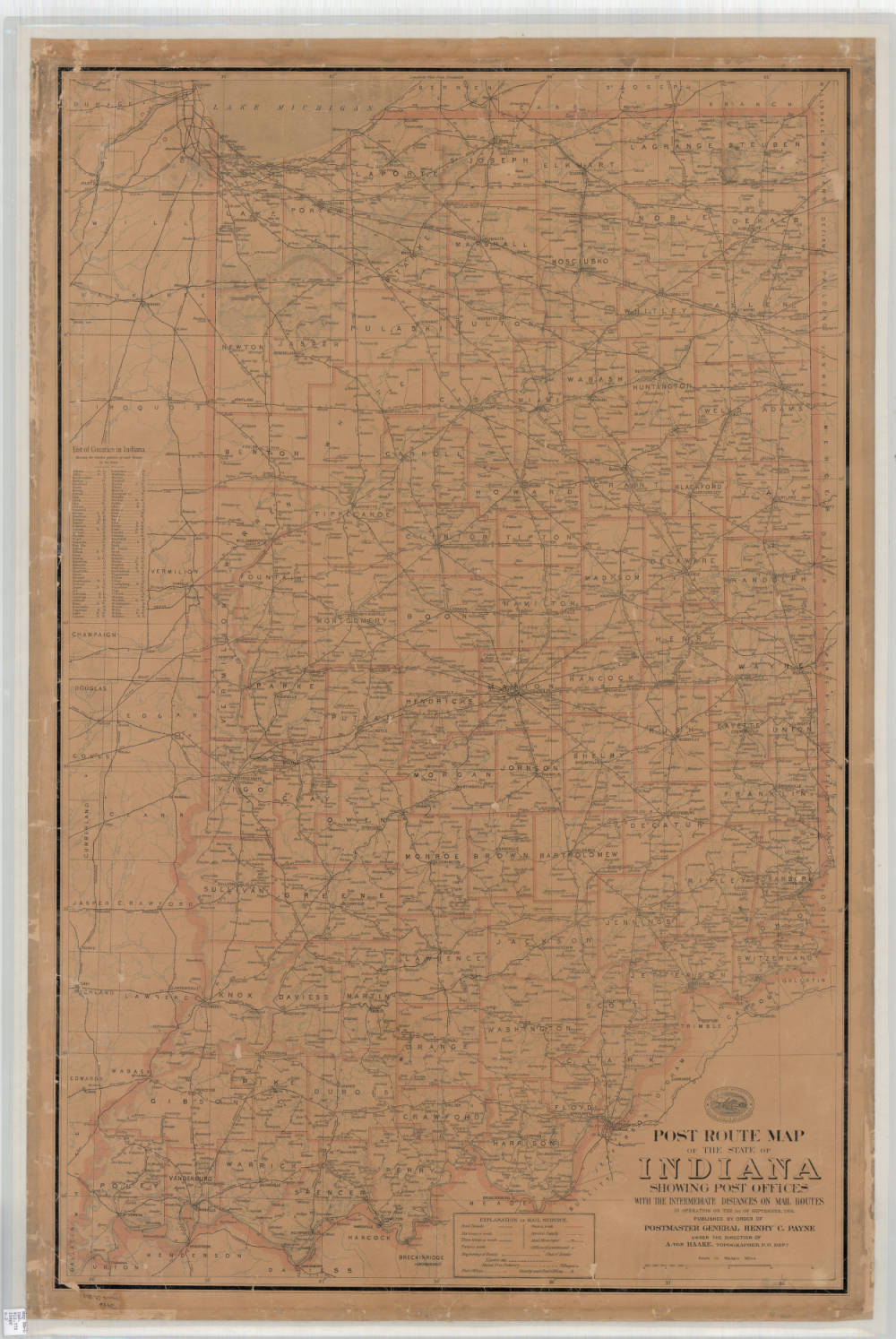

The rise of tourism in North America and Europe in the mid- to late 19th century caused difficulties for the existing passport and visa systems in Europe and in 1861, France abolished passports and visas, with the rest of Europe following suit. The U.S. continued issuing passports and many Americans still requested them to travel abroad for business, pleasure and to visit family. Over 369,844 passports were granted between 1877 and 1909, indicating the growing popularity of world travel in the late-19th and early 20th centuries.

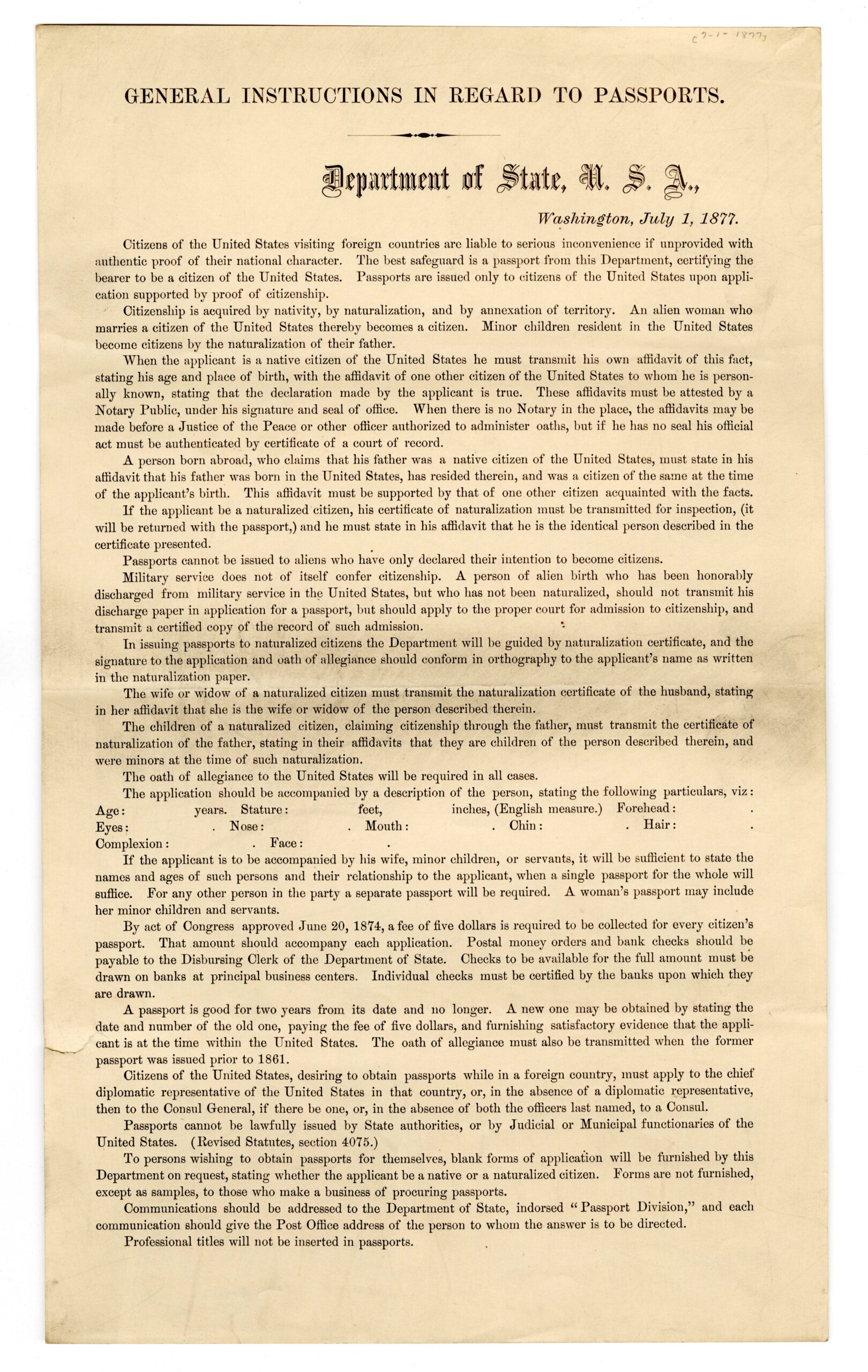

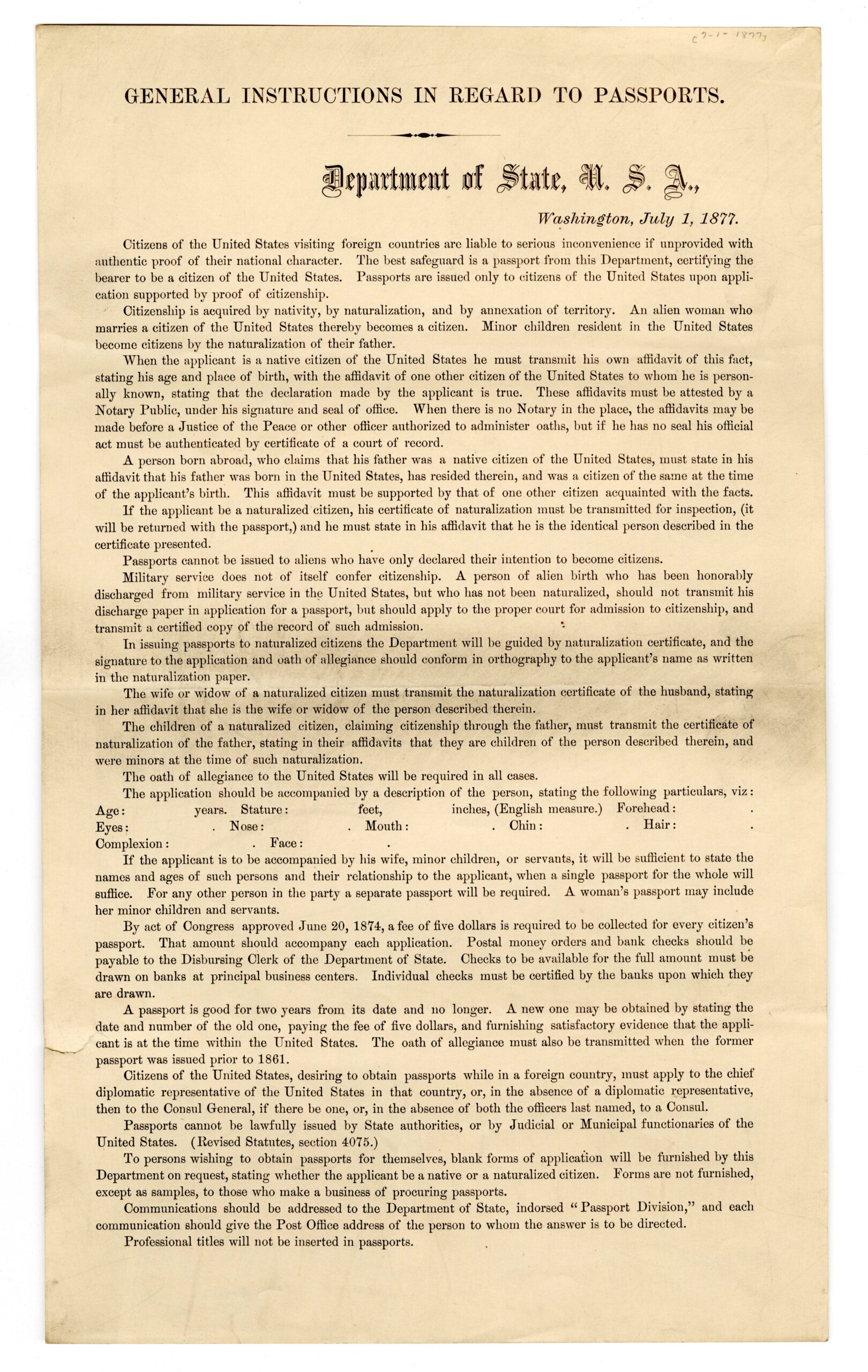

Until the mid-1800s, it cost nothing to obtain an American passport. The first passport fee of $3 was imposed by Congress in 1862. The fees fluctuated wildly over the next several decades: first rising to $5 in 1865; dropping to zero during 1870-1871; up to $5 again in 1874; then $1 in 1888. The fees then stabilized until 1917 when they rose to $2, before jumping to $10 in 1920 – the most dramatic increase since passport fees were implemented 58 years earlier. Passport fees often made attaining them a luxury for many Americans, especially when they were not required to travel.

U.S. Department of State, “General instructions in regards to passports” document (S3463), Rare Books and Manuscripts, Indiana State Library.

By the outbreak of World War I in 1914, passport requirements were nonexistent nearly everywhere in Europe and the United States. The First World War brought new concerns for international security, prompting the requirement of passports and visas to travel abroad. In 1920, the League of Nations advocated the concept of a worldwide passport standard, introducing the modern passport format of a small booklet with pages for stamps. Most countries around the world began implementing the new uniform passport guidelines set forth by the League and agreed to continue or add passport requirements. In contrast, the U.S. passport requirement was only a war measure that officially ended when President Wilson left office in 1921. The U.S. was not a member of League of Nations – despite it being the brainchild of its aforementioned president – and did not require passports for international travel again until Nov. 29, 1941, mere days before the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

During the early 1920s, passports were still seen as ephemeral forms of identification so most early booklet passports were not meant to last. Passport covers made of paper were commonplace, as indicated by the 1923 German passport of Erich L. Riesterer, which was taped several times as it fell apart.

[slideshow_deploy id=’8166′]

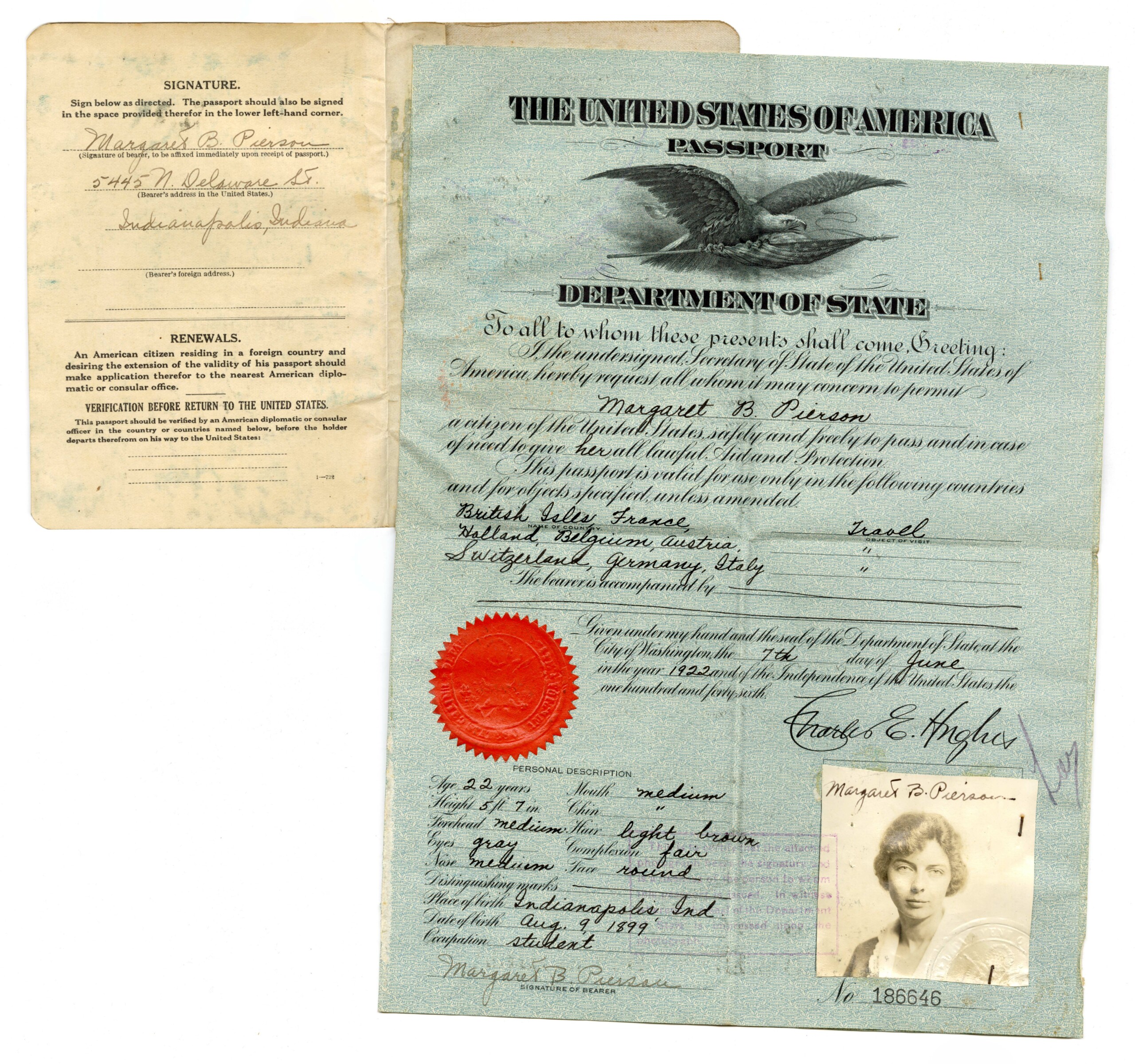

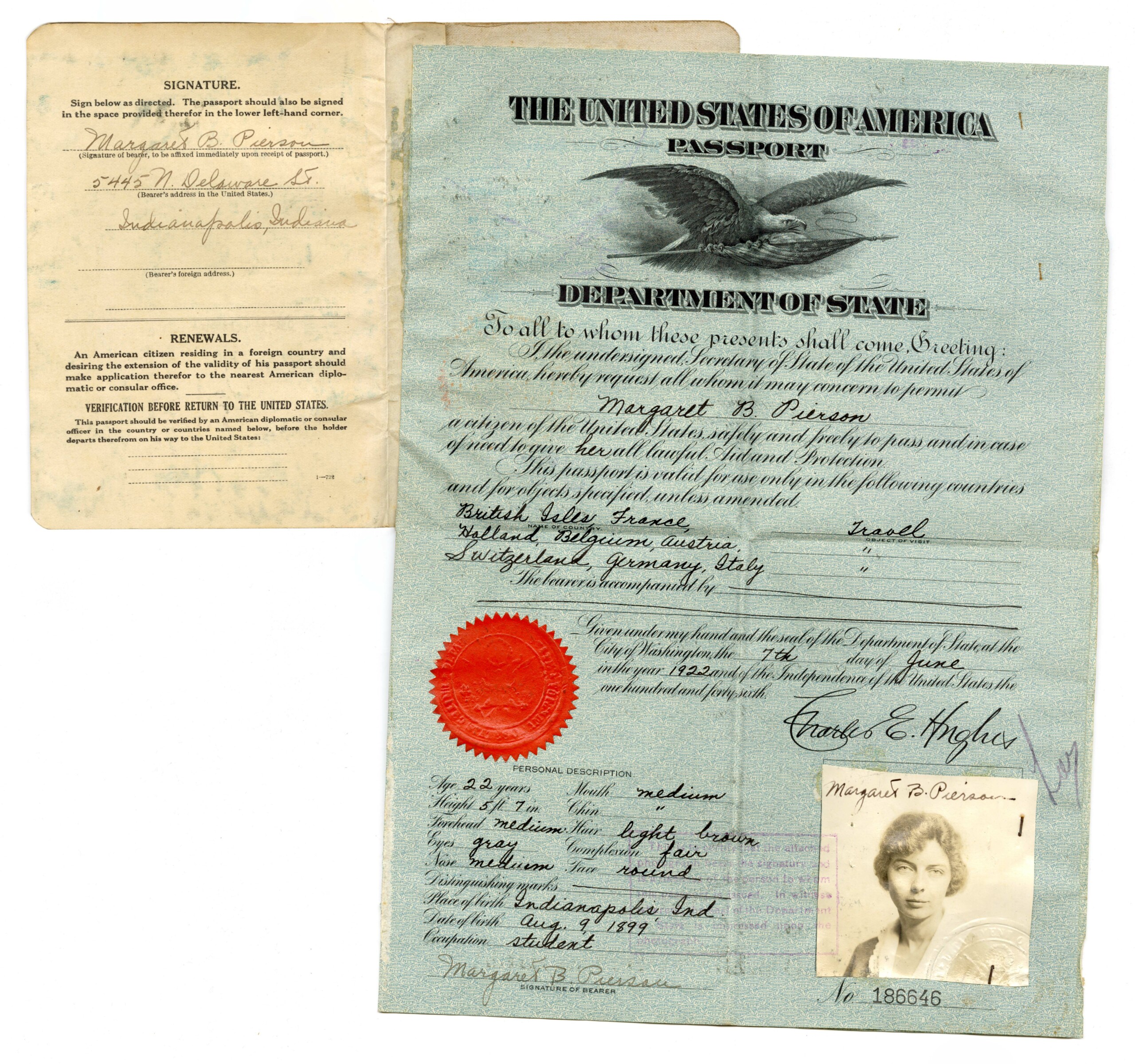

Post-World War I, the United States began issuing passport booklets with cardboard covers, but early on, the pages were large foldouts as seen in the 1922 passports of Margaret B. Pierson and the Marshalls in the next section. Regardless, passports were becoming necessities for American travelers if they wanted to visit countries that required them for entry. Interest in leisure travel surged after the war’s end, and when passport application fees dramatically increased in 1920, international travel grew far less feasible for people of limited means. Effectively, the passport requirements of other countries made obtaining an American passport a necessity to cross their borders, sometimes with the addition of costly visas.

Women with wanderlust

During the mid-19th century, men comprised 95 percent of passport applicants. If they were accompanied by dependents – such as wives, children, servants or female wards- their companions’ names, ages, and relationship to the man were stated on the application, if not the passport itself. Oftentimes, women were not even named on a man’s passport, simply denoted by “and wife.” Until the early 20th century, passports for married women in the United States and elsewhere were generally considered unnecessary. Instead, women continued to appear as mere afterthoughts on their husbands’ passports. The idea that a married women might need or desire to travel without their spouses was apparently inconceivable to their governments, while men could cross borders freely without their partners.

The following passports illustrate the differences between travel documentation for women based on their marital status. The first image shows the passport of a single woman, mathematician Margaret B. Pierson, issued on June 7, 1922. It includes her full name, physical description, date of birth, occupation and photograph, as well as the countries she intended to visit.

Margaret B. Pierson passport, 1922. Source: Margaret B. Pierson papers (S1038), Rare Books and Manuscripts, Indiana State Library.

The second example is the passport of Thomas Riley Marshall, former Indiana governor and Woodrow Wilson’s vice president, which includes his wife, Lois Kimsey Marshall. The only indications of her inclusion in the document are her photograph and the addendum that Marshall would be “accompanied by his wife Lois K.” on the first inside page.

[slideshow_deploy id=’8176′]

By 1923, American women comprised over 40 percent of passport applicants, according to the National Archives. The passport of Mrs. Cora Calhoun Horne illustrates the new independence a married woman achieved by having her own travel document when she set off to tour Europe in 1929 accompanied, not by her husband, but by her female friend. Aside from the prefix of “Mrs.,” the only mention of her husband on her identification is the contact information provided “in case of death or accident.”

[slideshow_deploy id=’8180′]

Unlike Horne, who took her husband’s surname, American women who retained their own names after marriage still had a bone to pick with State Department. The same year women attained the right to vote, writer Ruth Hale was issued a passport identifying her as “Mrs. Heywood Broun, otherwise known as Ruth Hale” despite having applied under her maiden name. In response, she cofounded the Lucy Stone League, which fought for a woman’s right to her maiden name. These women viewed passports as vital to their independent identities: if the State Department recognized the use of their birth names, then other government entities would surely follow. Despite a token victory in 1925 when press agent Doris Fleishmann, after several failed attempts, received a passport issued under her birth name, most women’s passports still recorded their identity as the wife of their husband. Finally, Passport Division supervisor Ruth Shipley unceremoniously dropped marital information on passports in 1937.

Horne’s trip abroad was noteworthy in another way. A middle-class African American woman living in Brooklyn, New York, Horne had both the means and the ability to apply for a passport and to travel abroad. Considering the immense legal and economic hardships facing Black Americans during the 1920s due to racial discrimination, Jim Crow, and the scarcity of educational and financial prospects, she had opportunities that many did not. Due to the discrimination facing them at home, having a passport and the resources to travel afforded many African American women and men – some of them performers, athletes and pioneers in their fields – greater opportunities outside the United States in the early to mid-20th century. World-renowned singer, actress and activist Lena Horne, Cora Calhoun Horne’s granddaughter, exemplified this trend.

“Recent” history

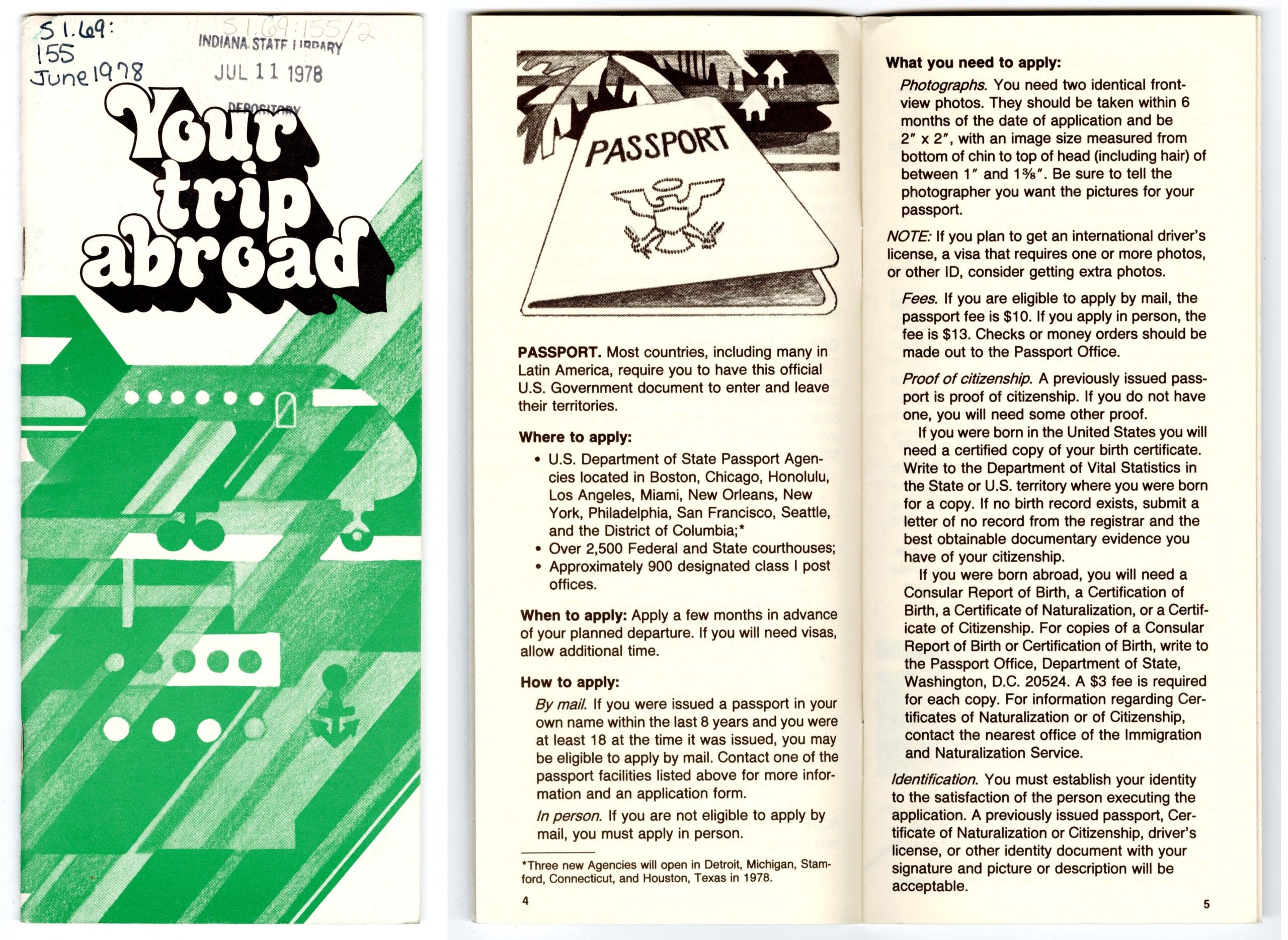

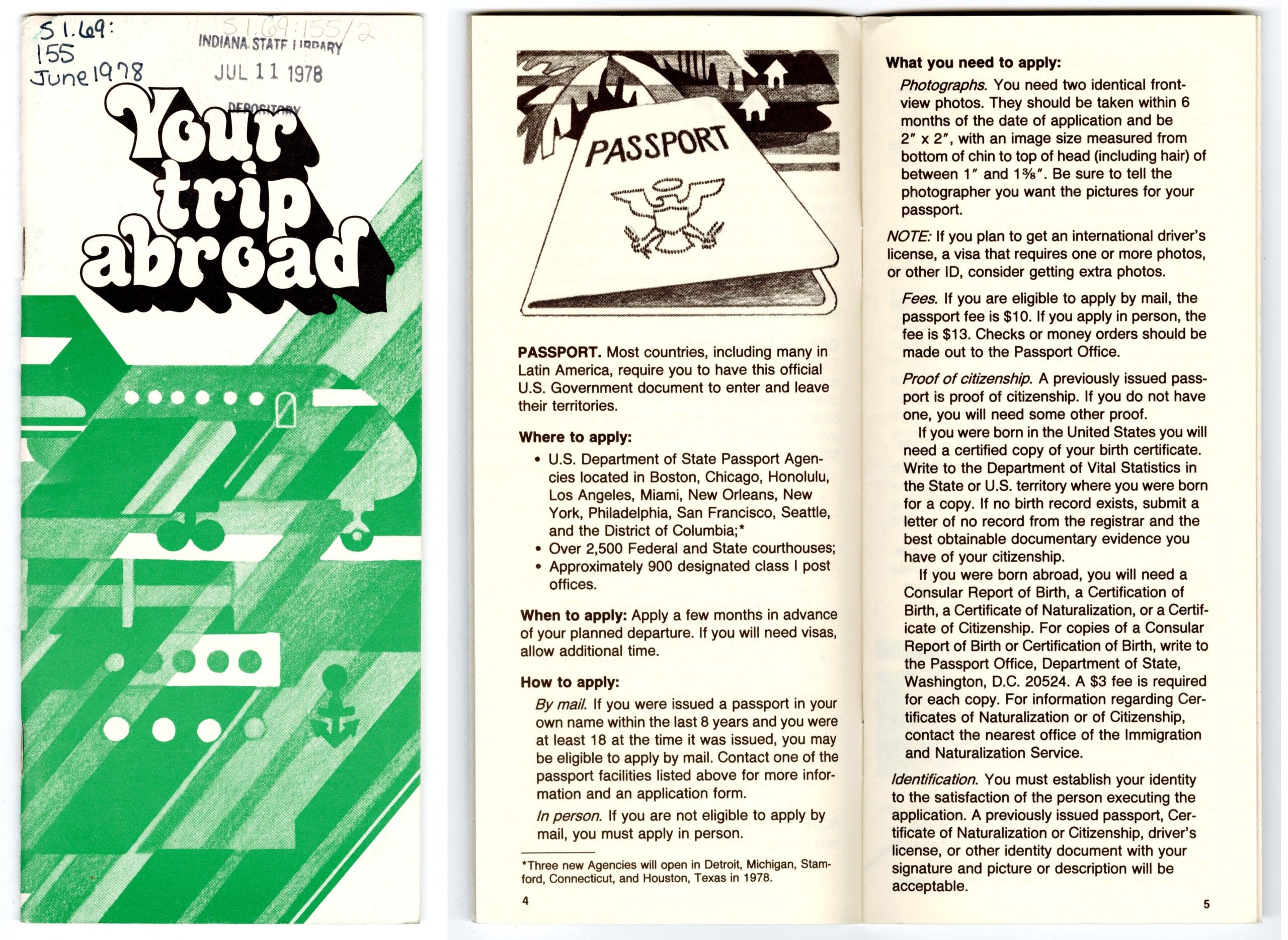

As illustrated by the above images, passports grew less ephemeral, undergoing a rapid transformation from the single-page document to a booklet. Beginning in 1926, American passports transformed into true pocket-size booklets with numerous pages and covers composed from more durable materials like the passports of today. Lengthier validity periods took a while to catch up to the more hardwearing form. The period until expiration for American passports increased from two years to three in 1959; to five years in 1968; and to the current ten years sometime after 1976. In essentials, the U.S. passport’s design essentially remained unchanged until a redesign in 2007. The most notable additions to passports and travel control in the 21st century have been the incorporation of technology, specifically microchips and biometrics. These changes in durability and longevity were the result of changes in how passports were utilized.

Following World War II, many countries used passports as a means of travel control due to subsequent global conflicts and national emergencies. In 1952, U.S. passport policy finally changed, requiring all American citizens to have passports to depart from or re-enter the United States, except for certain countries in North and Latin America. By this point, passports had become essential proof of citizenship and identity, particularly in terms of national security. Today, passports are treated as the highest form of identification and used to obtain a driver’s license, open bank accounts and secure housing and employment.

“Your Trip Abroad” pamphlet (U.S. Department of State), 1978. Source: General federal documents, Reference and Government Services, Indiana State Library.

Dramatic changes to society – caused by complex factors such as industrialization, increased access to education, the enfranchisement of women and people of color and war – shaped the role of U.S. passports, and their appearance, during the 19th and 20th centuries. Travel documents evolved from optional, transient means of protection and mobility for the mostly male Euro-American elite, to methods of establishing identity. For the newly enfranchised, like BIPOC and female Americans, passports became symbols of their full citizenship and offered access to opportunities abroad when their rights as citizens were denied them at home. From the perspective of governments, passports became necessary instruments of national security and mandatory forms of identification for people crossing their borders. In this way, the passport was an instrument of protection and freedom to some, while others came to view it as a method of control.

Author’s notes:

- The title for the post was inspired by another one dated October 18, 2016 from fellow Manuscripts librarian Lauren Patton called, “A Brief History of the United States Passport.” It provides more detailed information about Watson J. Hasselman’s passport from 1873.

- This post is a companion piece to my exhibit, The Hoosiers Abroad, on display in the Manuscripts Reading Room at the Indiana State Library until mid-September.

- The history of passports is far broader and more complex than can be fully conveyed here. As our collection centers on Indiana history, and thus provides an abundance of European and American experiences through the mid-20th century, the focus of this post is necessarily limited and does not explore the history of passports in other cultures or parts of the world, nor the impact of imperialism and colonialism upon those cultures. There is much more to study on this topic, including the experiences of Americans of color and the working classes. Particularly, I wish to see more scholarship related to African Americans’ use of passports during the late 19th and 20th century as most of works I encountered ended at the Civil War period. Hopefully, this gap in the literature will eventually be addressed by scholars, allowing for an updated “Not-so-brief history” sometime in the future.

This blog post was written by Rare Books and Manuscripts librarian Brittany Kropf. For more information, contact the Rare Books and Manuscripts Division at 317-232-3671 or via “Ask-A-Librarian.”

Sources

Items from the Indiana State Library collection.

Government of Canada. “History of Passports.” Canada.ca. Modified April 10, 2014. https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/services/canadians/celebrate-being-canadian/teachers-corner/history-passports.html

Knisely, Sandra. “The 1920s Women Who Fought for the Right to Travel Under Their Own Names.” Atlas Obscura, March 27, 2017. https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/us-passport-history-women

Little, Becky. “See How Women Traveled in 1920.” National Geographic, August 24, 2018. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/travel/article/women-equality-day-history-politics-passport

Pines, Giulia. “The Contentious History of the Passport.” National Geographic, May 16, 2017. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/article/a-history-of-the-passport

Puckett, Jessica. “How the U.S. Passport Evolved from Status Symbol to Essential Travel Document.” Condé Nast Traveler, May 1, 2020. https://www.cntraveler.com/story/how-the-us-passport-evolved-from-status-symbol-to-essential-travel-document

Sharp, Rebecca. “A Rare Find: Passport Applications of Free Blacks.” Rediscovering Black History blog, July 22, 2020. https://rediscovering-black-history.blogs.archives.gov/2020/07/22/a-rare-find-passport-applications-of-free-blacks/

United States Passport Office. The United States Passport: Past, Present, Future. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1976.

United States National Archives and Records Administration. “Passport Applications.” National Archives. Last reviewed October 27, 2021. https://www.archives.gov/research/passport

United States National Archives and Records Administration. “Passport Applications, 1795-1925.” National Archives. Last revised November 2014. https://www.archives.gov/files/research/naturalization/400-passports.pdf

Wikipedia. “Passport.” Wikipedia.org. Accessed August 28, 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Passport.

Wikipedia. “United States Passport.” Wikipedia.org. Accessed August 28, 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_passport.