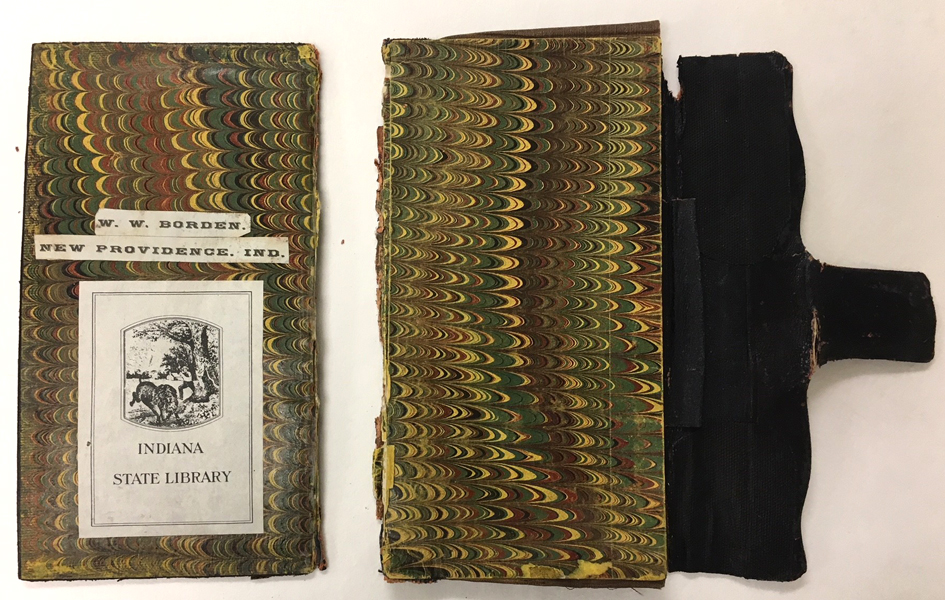

After a year with the Gunnar AiOx Hybrid XL boxmaking machine, the Indiana State Library has started to innovate in designs to improve performance and efficiency. While automated boxmaking was reducing the labor and materials cost per box, there were a number of areas where the templates included with the Gunnar Mat Creator software weren’t providing the best results for each type of box without modification.

As the new conservator for the library, I set a goal of learning to use the machine, making its use more efficient and improving the quality of the boxes. I have also connected with an online users’ group that includes members from the University of Texas, University of Pennsylvania and other libraries, learning from their years of experience designing custom templates for this machine.

As the new conservator for the library, I set a goal of learning to use the machine, making its use more efficient and improving the quality of the boxes. I have also connected with an online users’ group that includes members from the University of Texas, University of Pennsylvania and other libraries, learning from their years of experience designing custom templates for this machine.

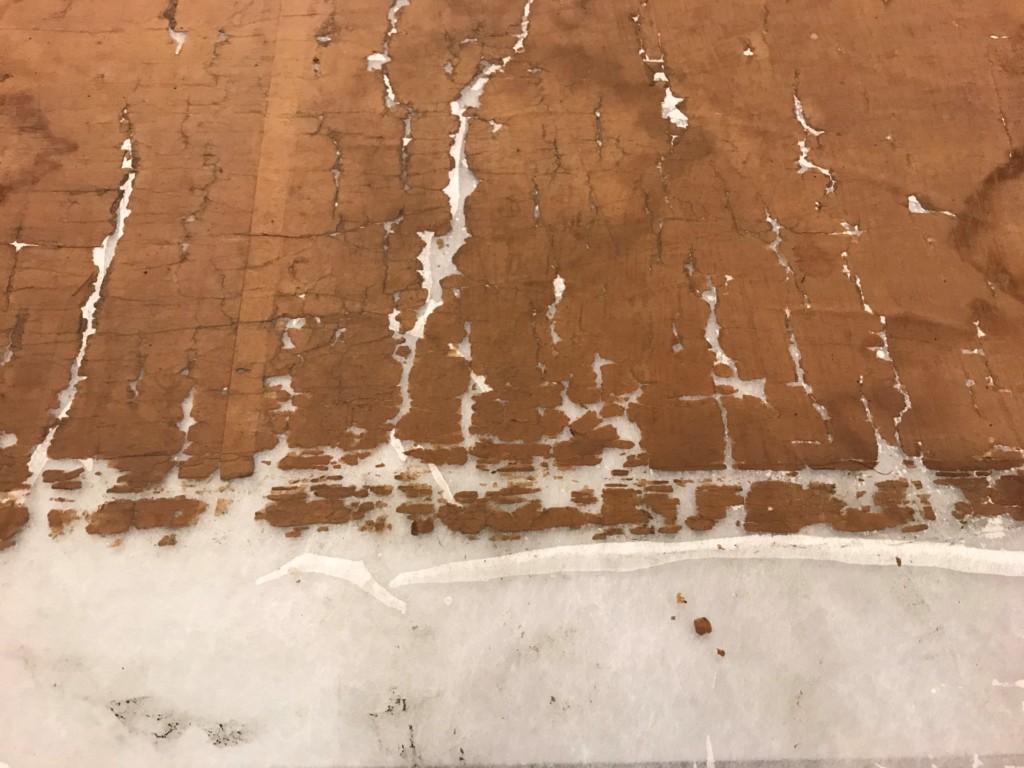

One area where library staff had struggled was in the use of the “nesting” feature. The software program would automatically place boxes in an arrangement on a sheet of acid-free corrugated board based on whether it was 32”x40” or 40”x60” without regard for the direction of the corrugations or ridges in the board. Box hinges that flex when the box opens will tend to crack and split when folded in the wrong orientation. I have revised our box instructions to reflect that the hinges must be aligned parallel to the ridges. In practice, this means that we had to rotate some of the boxes on the computer screen to fit in the correct direction on the board.

Another new process has been to redesign existing templates to use board efficiently. For example, we were using a magazine box template that came with the machine, adapted to fit the size we use in the library. It had a design that could only fit two boxes on a 40” x 60” board. I created two new designs that could fit four boxes on a single board. The new designs also were rotated so the vertical folds were aligned with the ridges in the board to make the boxes fold more neatly.

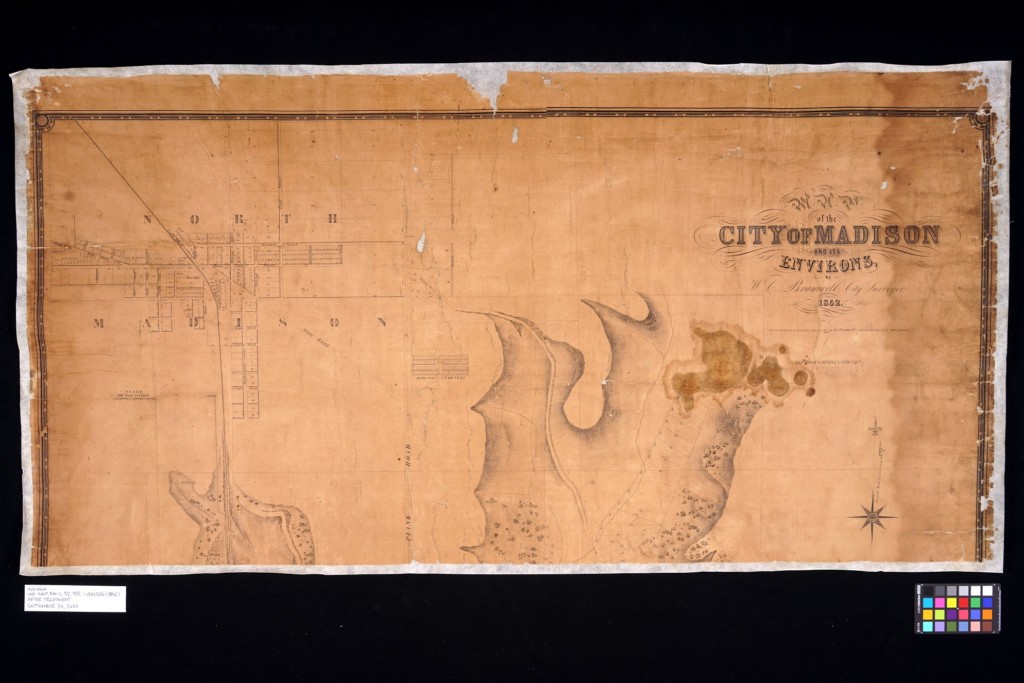

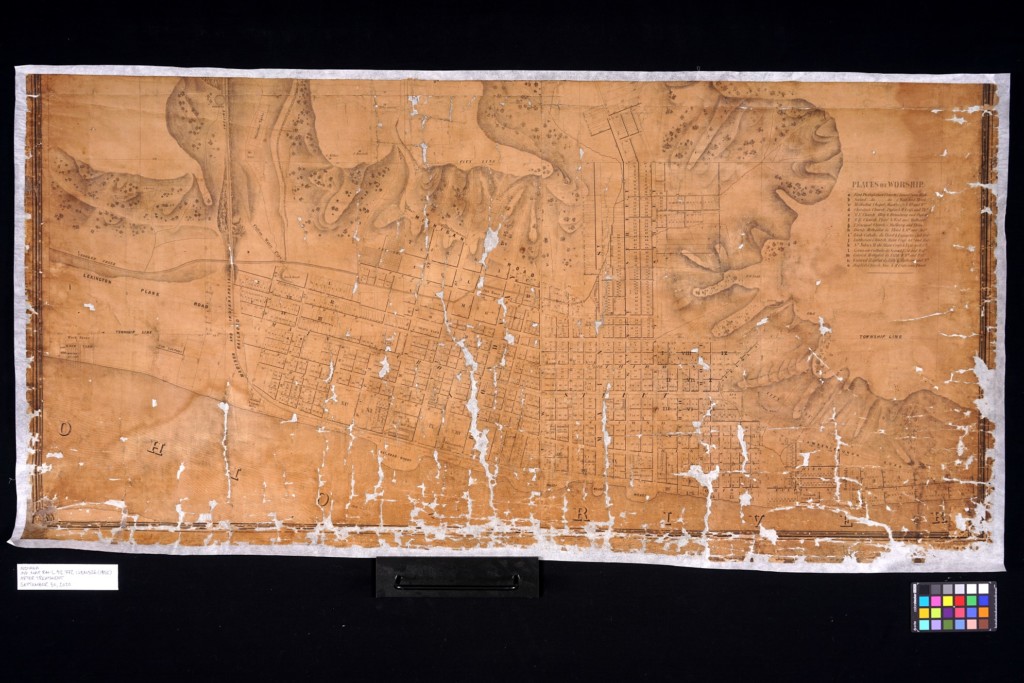

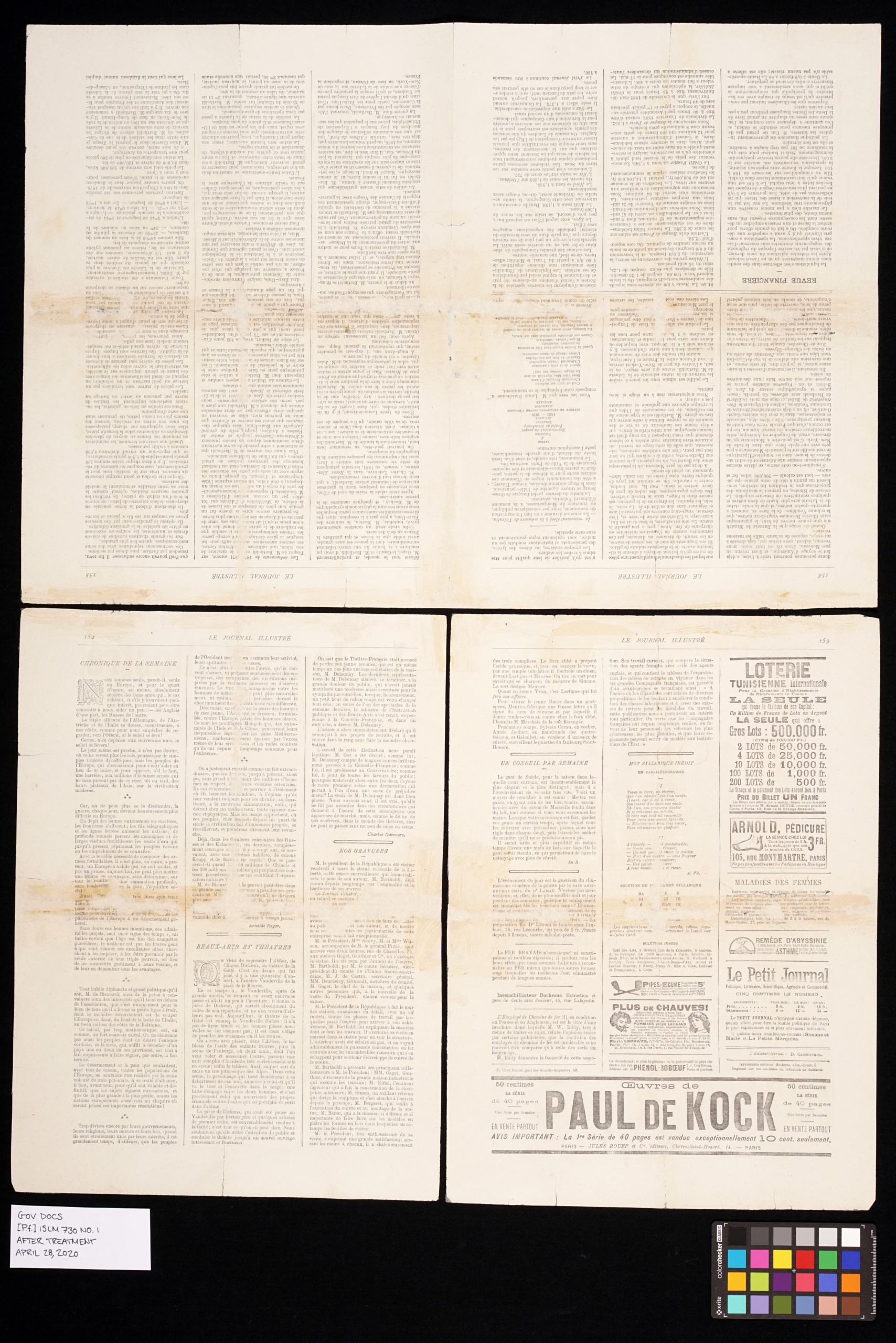

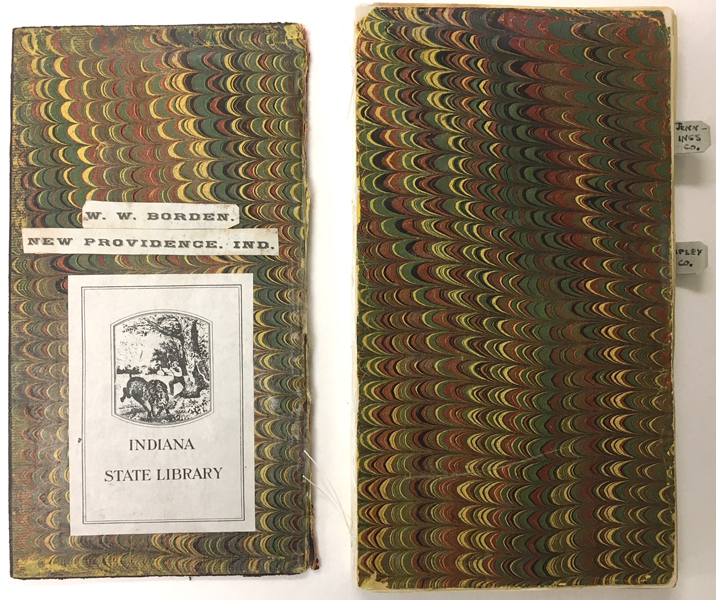

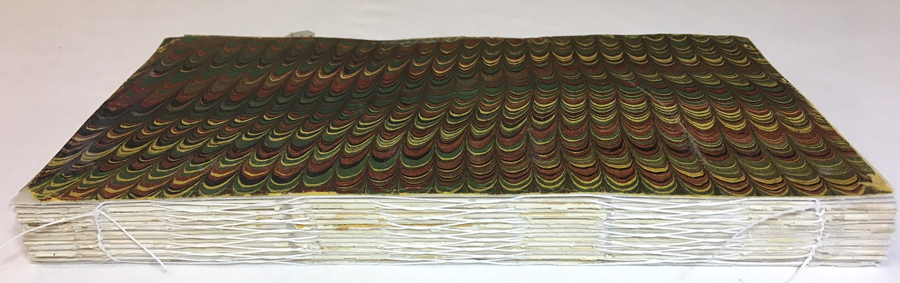

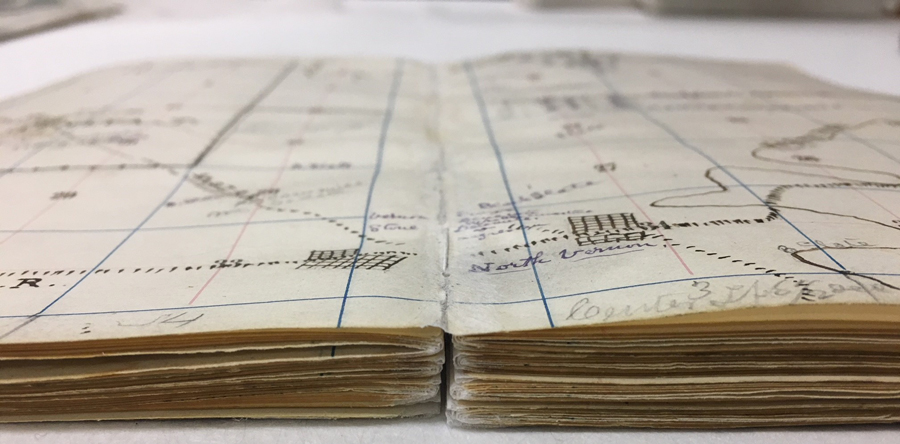

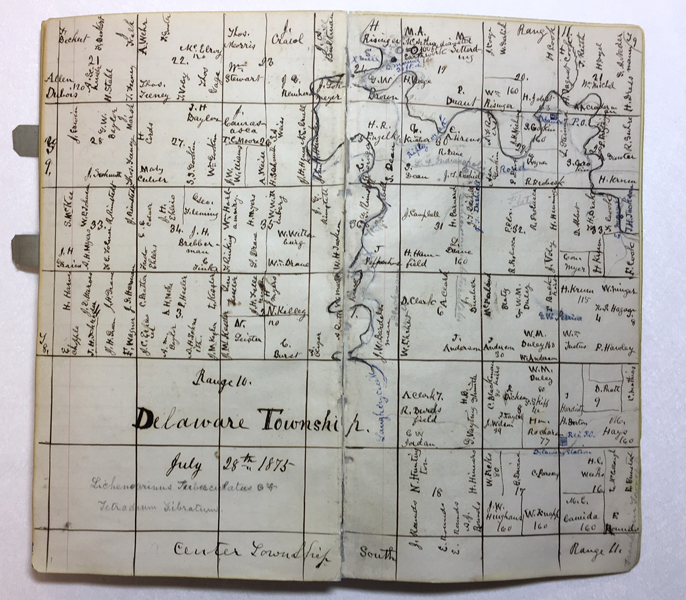

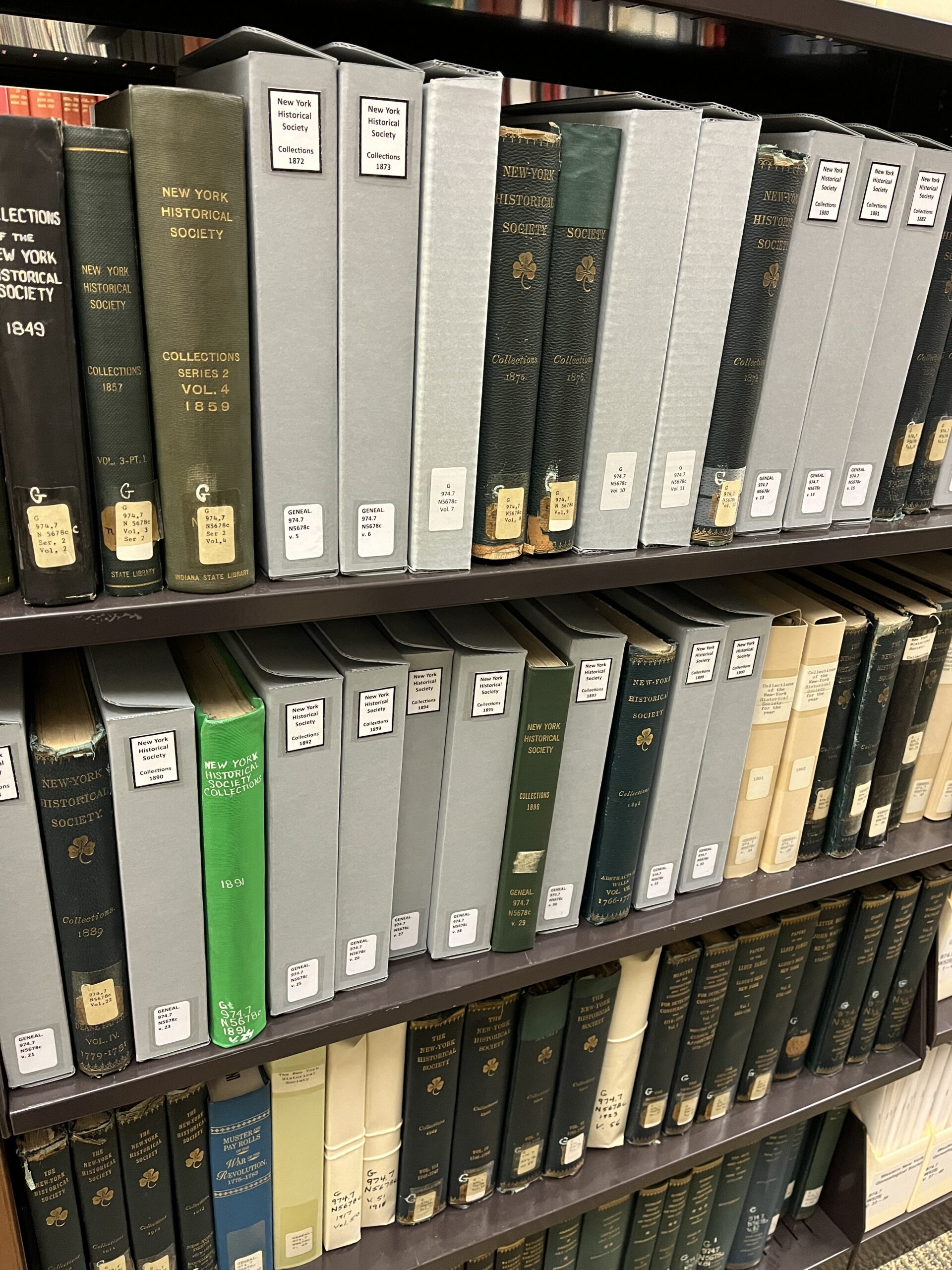

A third process was to move beyond the three basic box types in order to house a wider variety of materials. I designed a three-part box to house scrapbooks and unbound or disbound volumes of loose pages. This box was designed for items that will be stored flat, rather than standing up on a bookshelf. I also used this as the basis for a similar design that can use multiple trays for 3-dimensional objects in the collection. The outer box fits the same footprint as a standard manuscript box, while inner trays organize the contents.

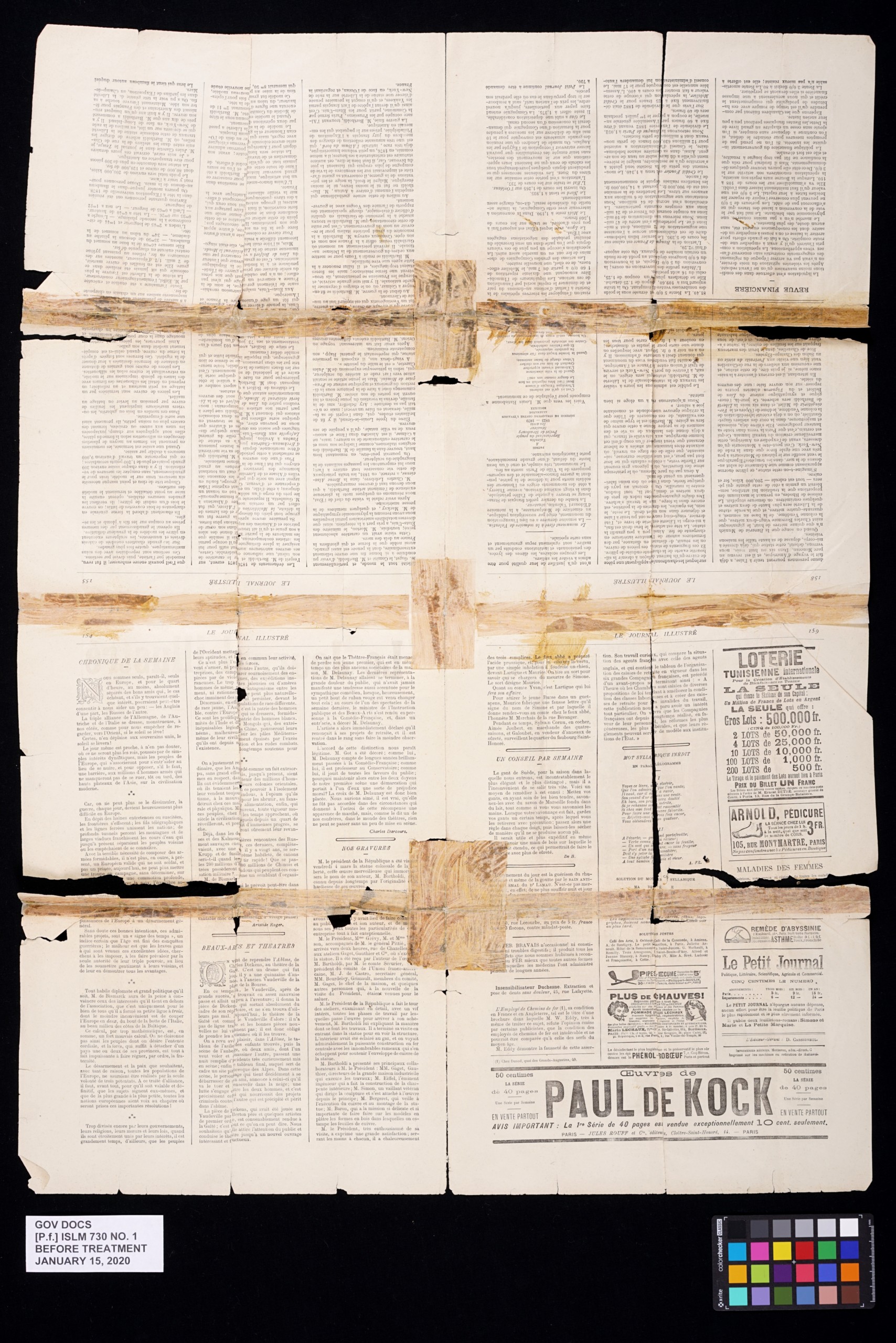

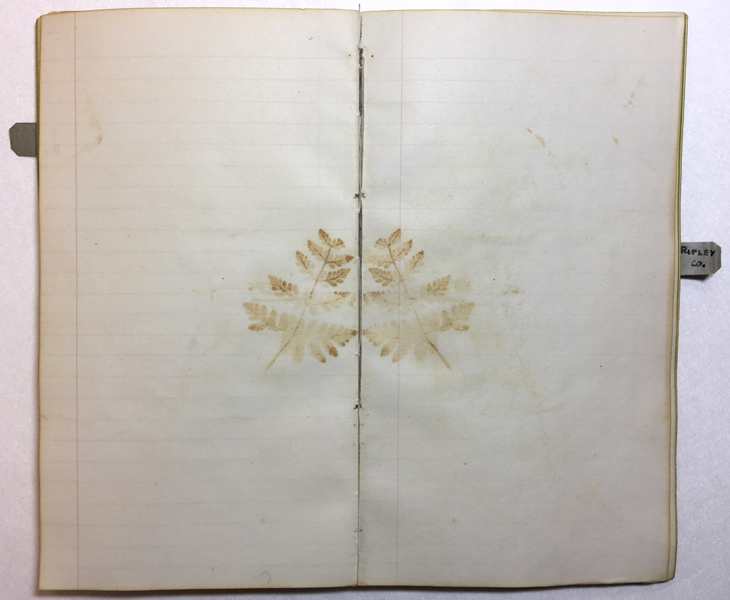

A shallower blade depth setting and slower cutting speed was used to cut folder stock, which is thinner and more dense than corrugated cardboard. This thin board can be used to make four-flap wrappers for pamphlets or slings for pamphlets stored in envelopes. Envelopes are not ideal for preservation, but a sling helps to reduce the damage caused by grasping the pamphlet to remove it or insert it into an envelope. This is a more cost-effective method of reducing the damage caused by inadequate older housings than replacing the envelopes with sturdier pamphlet binders or four-flap wrappers. The new four-flap wrappers will be reserved for fragile, high-use pamphlets, since they require more material and labor than a sling.

A shallower blade depth setting and slower cutting speed was used to cut folder stock, which is thinner and more dense than corrugated cardboard. This thin board can be used to make four-flap wrappers for pamphlets or slings for pamphlets stored in envelopes. Envelopes are not ideal for preservation, but a sling helps to reduce the damage caused by grasping the pamphlet to remove it or insert it into an envelope. This is a more cost-effective method of reducing the damage caused by inadequate older housings than replacing the envelopes with sturdier pamphlet binders or four-flap wrappers. The new four-flap wrappers will be reserved for fragile, high-use pamphlets, since they require more material and labor than a sling.

As I become acquainted with more of the library’s preservation needs, I find more opportunities to create new box templates. Often there’s an existing template that just needs a few changes, to add a drop-down front or a drop spine or to add tabs and slots to assemble the box without glue or to combine parts of two old templates. I look forward to continuing to maximize the efficiency of the Gunnar AiOx Hybrid XL.

As I become acquainted with more of the library’s preservation needs, I find more opportunities to create new box templates. Often there’s an existing template that just needs a few changes, to add a drop-down front or a drop spine or to add tabs and slots to assemble the box without glue or to combine parts of two old templates. I look forward to continuing to maximize the efficiency of the Gunnar AiOx Hybrid XL.

This blog post was written by the Indiana State Library conservator Valinda Carroll.