Last month, on Feb. 23, the Indiana State Library had the honor and privilege of welcoming Census Bureau director Robert L. Santos. He was here to visit the Indiana State Data Center and to listen to the Indiana SDC network of economists, librarians, GIS practitioners and other community partners share experiences about supporting the public with census data.

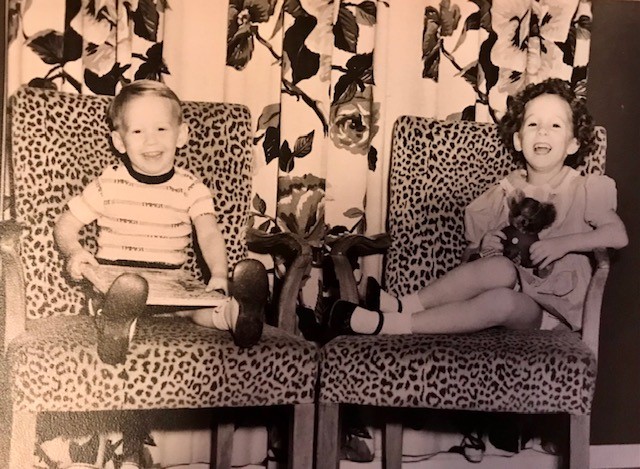

Director Robert Santos, Katie Springer and Jennifer Dublin on the stairs leading to the Great Hall in the Indiana State Library.

Director Santos grew up in San Antonio, Texas. He attended the University of Michigan, where he earned his graduate degree in Statistics, which spurred him toward a 40-year career as a statistician. He has served at many reputable institutions across the nation, including two here in the Midwest: the Institute for Social Research at the University of Michigan and the National Opinion Research Center at the University of Chicago.

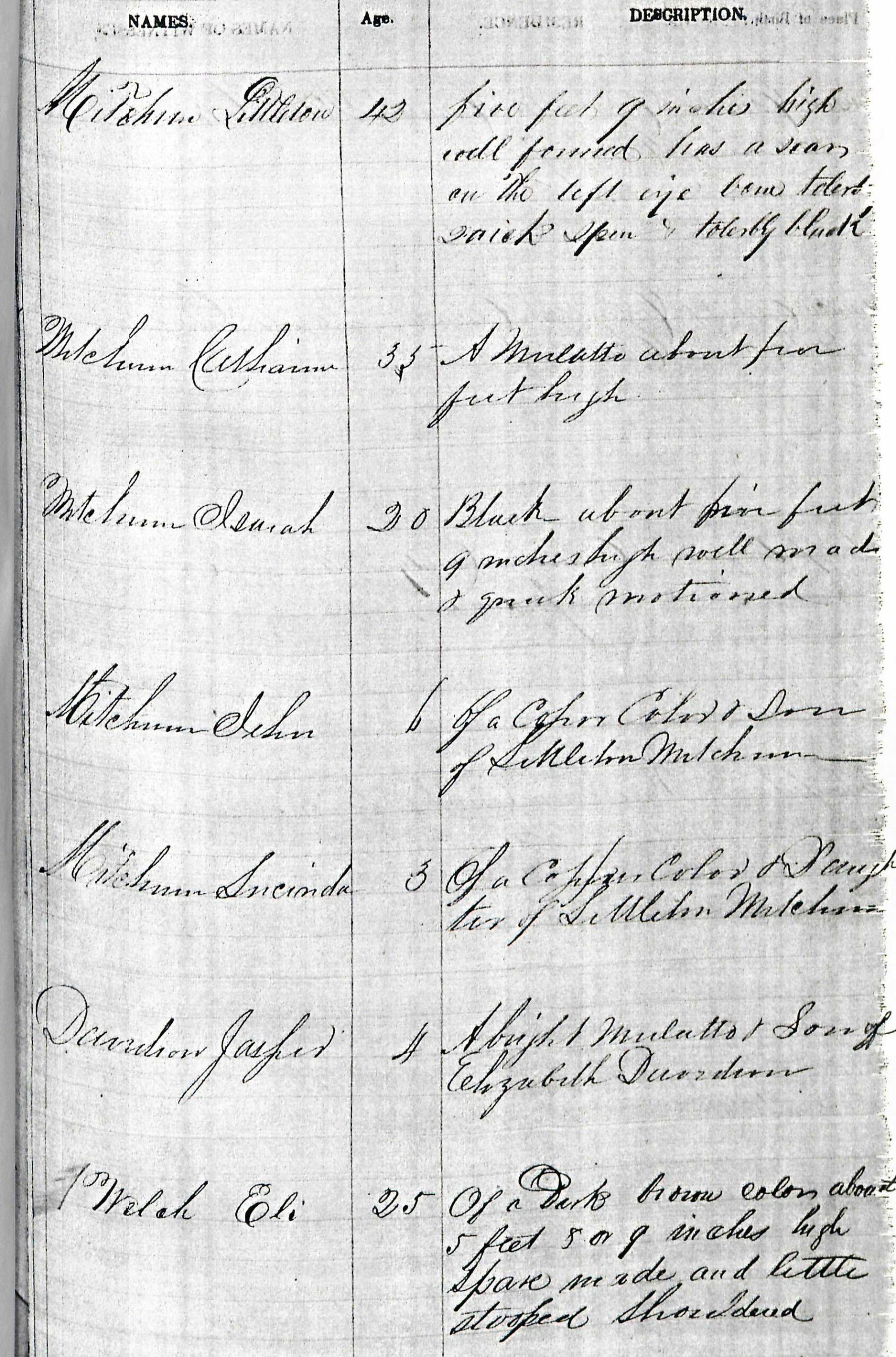

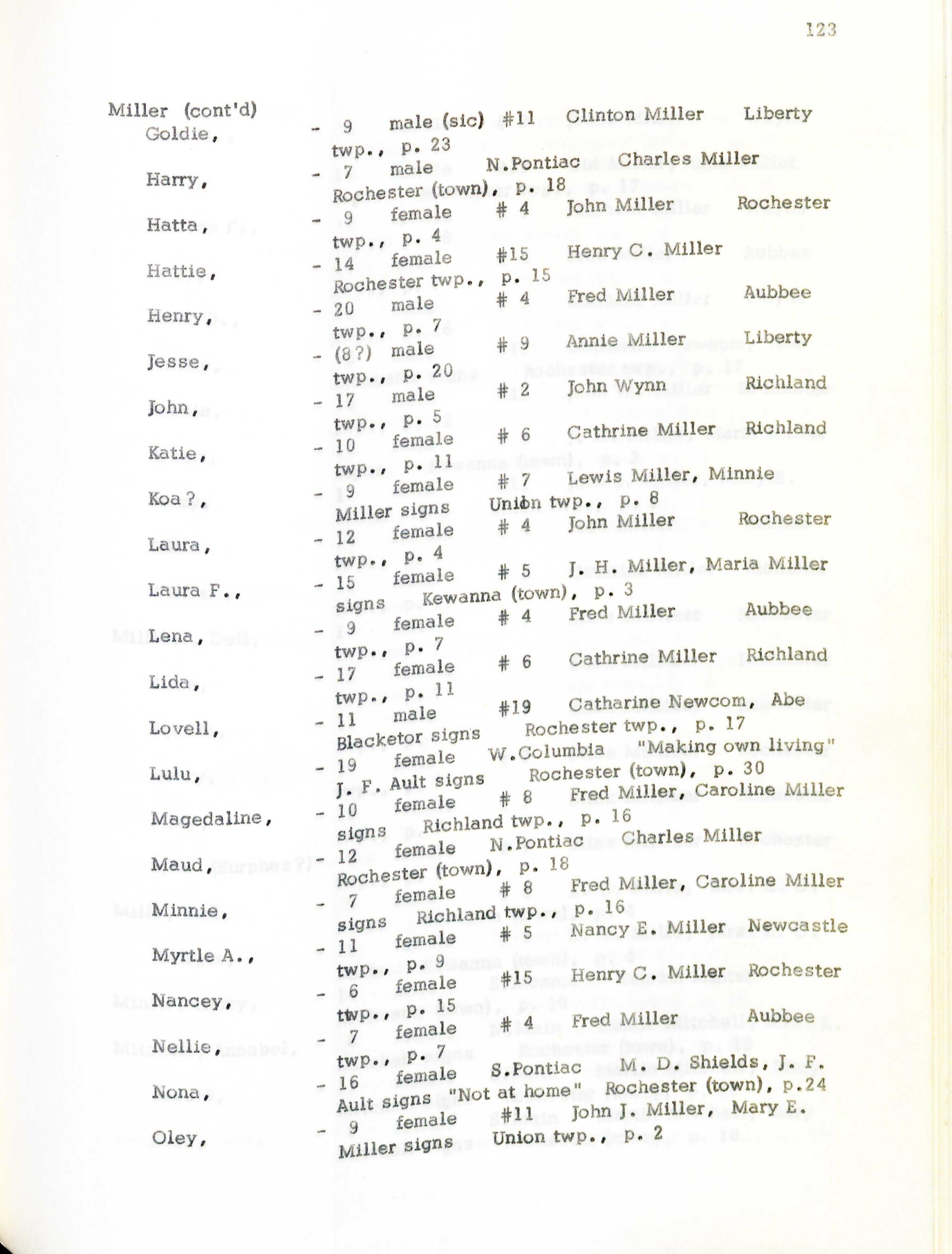

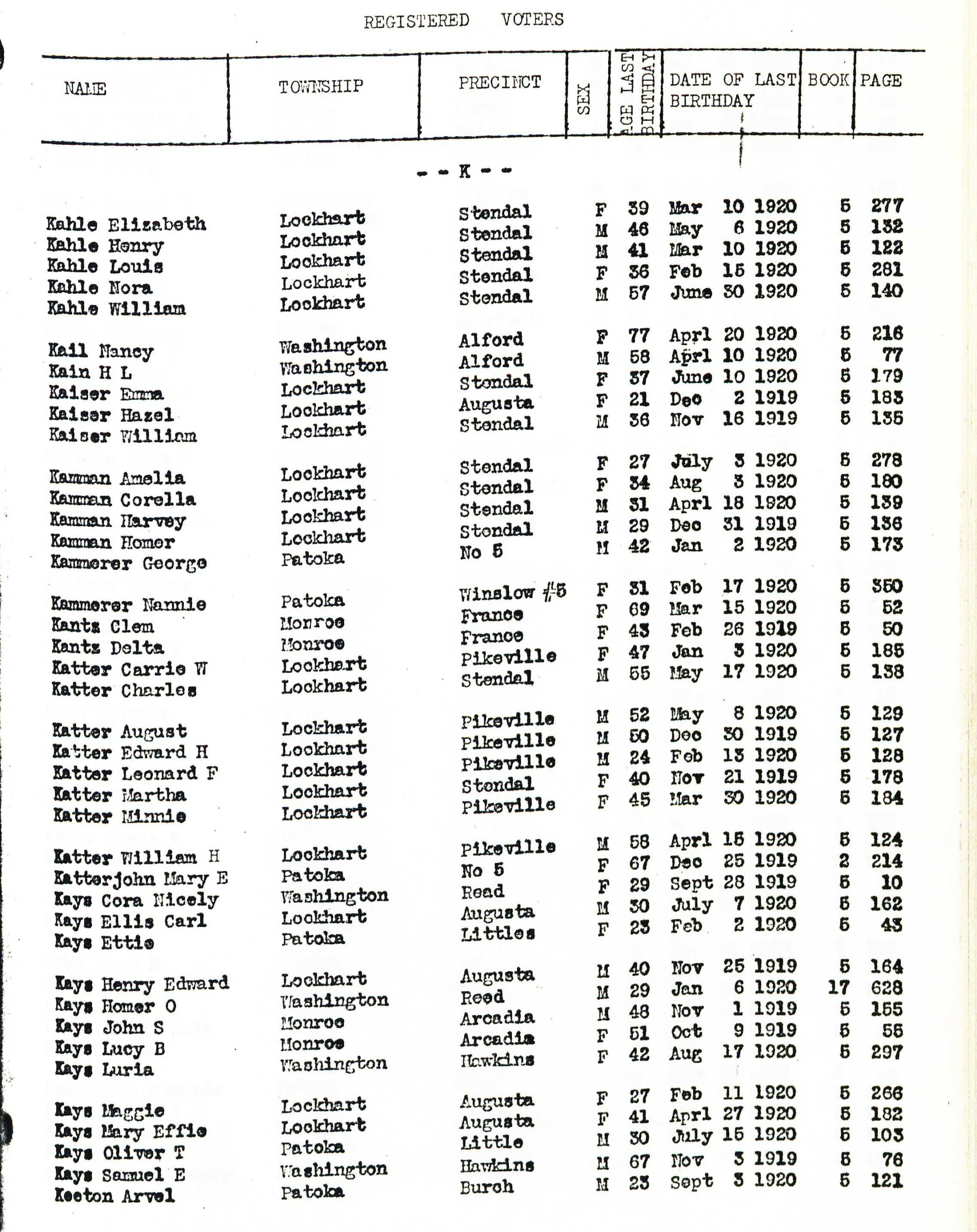

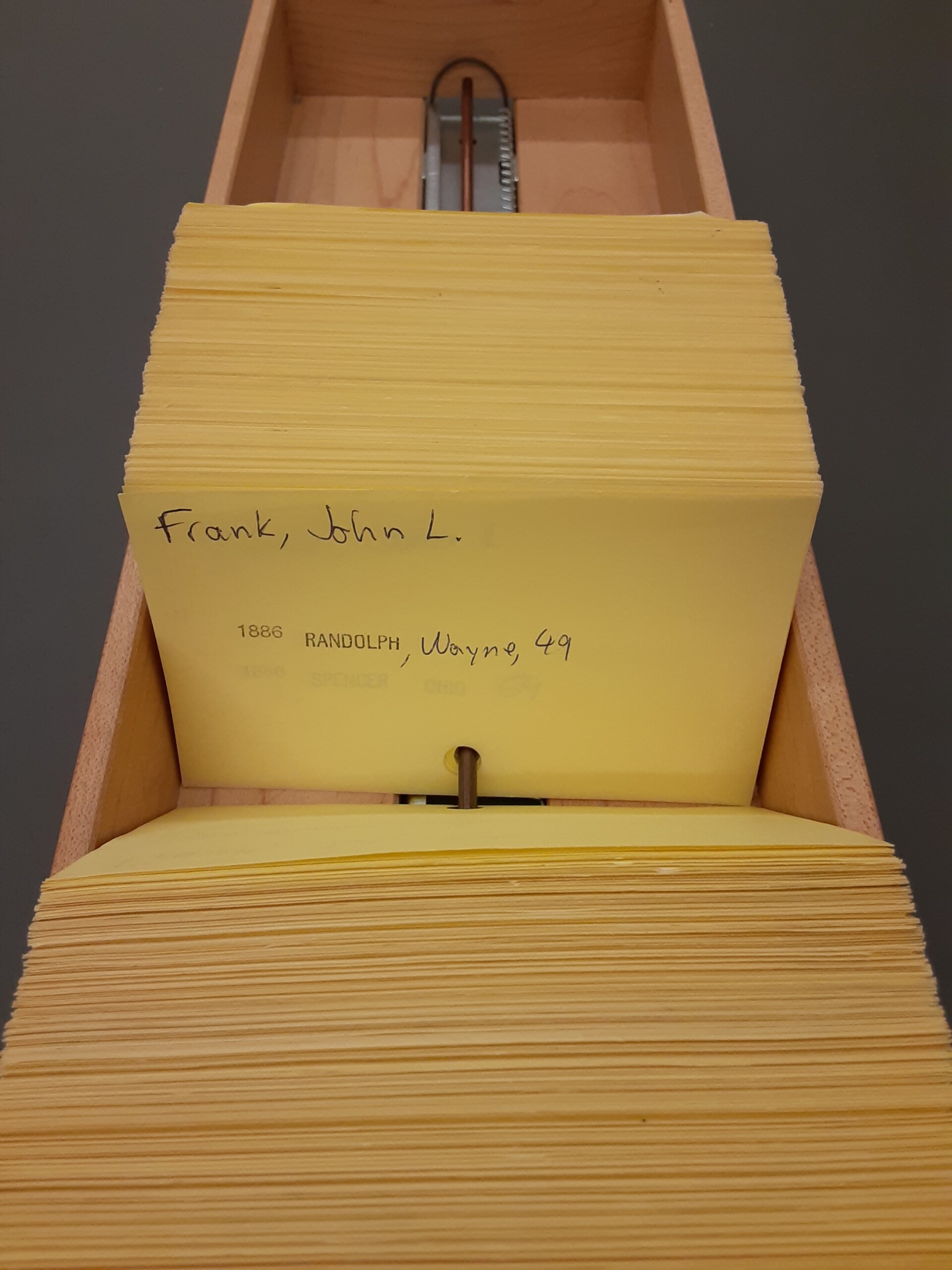

During his visit, we were happy to share with him the history of the Census Bureau’s State Data Center Program as it relates to Indianapolis. As Jeff Barnett, a former Indiana State Data Center manager, wrote in Indiana Libraries in 1986, the Census Bureau’s Indiana Census Users Service Project was started here as an experimental program to gauge the needs of Indiana data users. In the spring of 1976, ICUSP staff visited over 150 Hoosier organizations to gather information on local census data usage from data users across the state. Libraries, universities and other community organizations participated in providing information to the Census Bureau. This was the framework for what would become the national State Data Center program in 1978. State Data Centers in four other states – the “prototype” SDCs according to Jerry O’Donnell of the Census Bureau – were the first to sign agreements with the Bureau in the late 1970s, as described by Michele Hayslett in Reference & User Services Quarterly in 2006.

Over the past four decades, this national network has grown to include State Data Centers in all 50 states, Puerto Rico and the Island Areas. We work in collaboration with the Census Information Centers to provide data access and training to communities who need us.

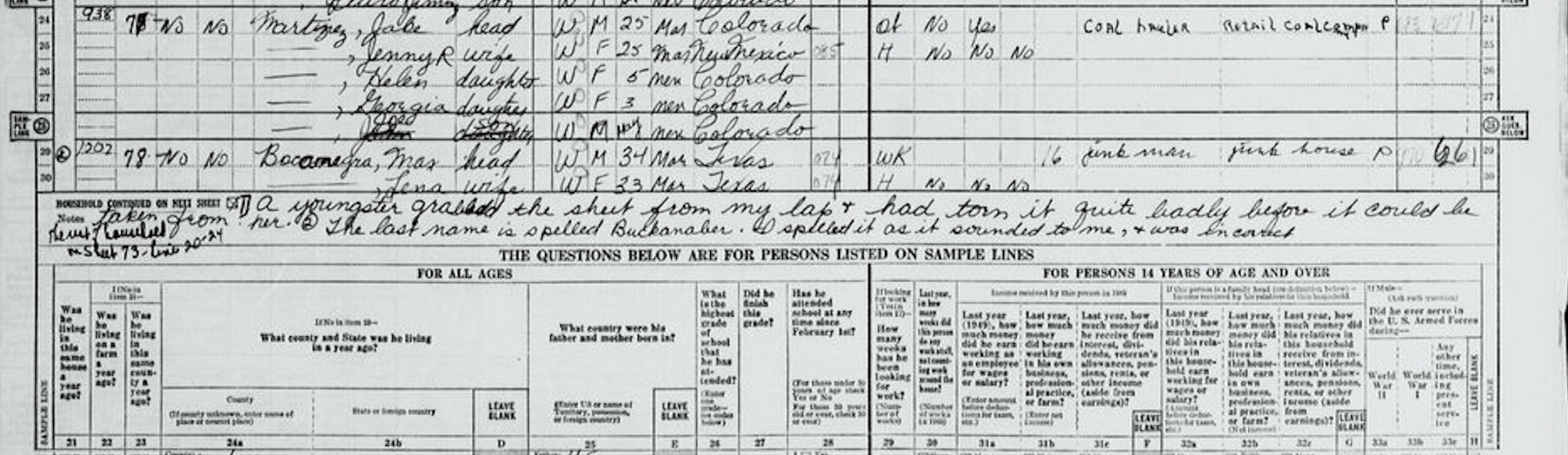

Director Robert Santos facilitates a discussion with the Indiana SDC Network at the Indiana State Library.

At the heart of the SDC-CIC program is the data user – who they are, what they need, how they work and what they’re thinking. We perform outreach face-to-face, by phone and online, reaching data users where they are. Here at the Indiana State Data Center, we hold our monthly Indiana Data User Group – known as IN-DUG – meetings and issue our quarterly newsletter, DataPoint. We keep the conversation going among our many partners on Listservs and social media. The State Data Center is open during State Library hours, five days per week and on one Saturday per month. The library is also available for data requests 24/7 through Ask-A-Librarian.

As Santos pointed our during his visit, actively and consistently engaging with diverse stakeholders for the best quality statistics is a continuous process throughout the decade. Data users need assistance in real time using census data that holds value for them. The SDCs and CICs are the bridge across the divide between expert and user. We help you locate, analyze and map the key data to feature in your story about your community. Ask us!

This blog post was written by Katie Springer, reference librarian and director of the Indiana State Data Center. For more information, contact the Reference and Government Services Division at 317-232-3678, or submit an Ask-A-Librarian request.