Once upon a time, Indiana was considered the hot destination to elope in the eastern Midwest. In the late 19th century, many states enacted stricter stipulations for obtaining marriage licenses, requiring long waiting periods, higher age limits, officiant qualifications, and later, medical examinations, before a couple could wed. That was not the case in Indiana. On February, 6, 1883, suffragist and author Harriot Eaton Stanton Blatch wrote to businessman Henry Douglas Pierce of Indianapolis, saying she had informed an Englishman interested in American marriage laws that “Indiana is our most liberal state.” In the Hoosier State, a couple could get married without delay, so long as they could find an officiant to do the deed. Several shrewd entrepreneurs sensed a ripe business opportunity and “marriage mills” sprung up in several Indiana border towns as early as the 1870s. Although these businessmen formally held the office of justice of the peace, they were known by other epithets, such as magistrates and “marrying squires.”

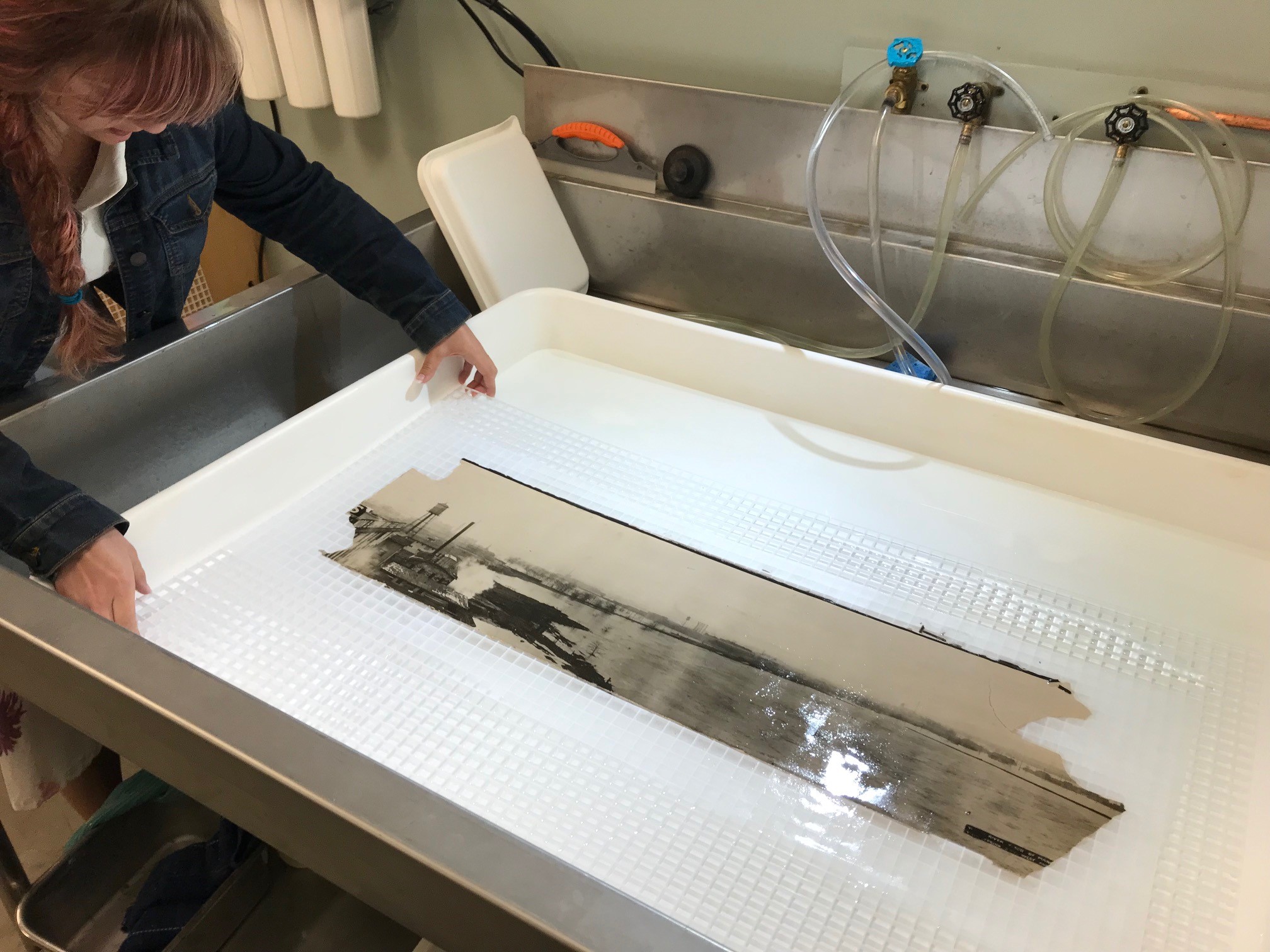

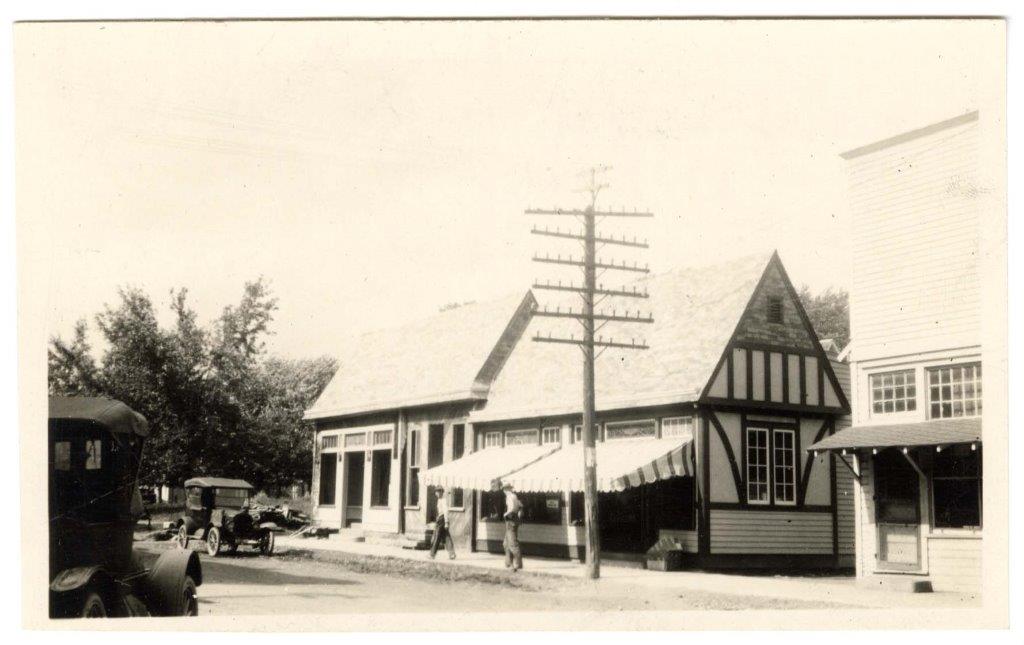

Magistrate waits expectantly outside Jeffersonville marriage parlor, ca. 1931 / Cejnar family collection, ISL

While these matrimonial market towns evoke visions of Las Vegas to the modern reader, they were often referred to as “Gretna Greens” at the time, alluding to the notorious Scottish town just over the border from England where many young men and women of England and Wales ran away to get married. Like Indiana, Scotland had less strict marriage laws than its neighbors during the 1770s to 1850s and local business owners, like blacksmiths, capitalized on the demand for speedy weddings. Indiana experienced a similar phenomenon. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, hundreds of thousands of keen couples from Kentucky flocked to Jeffersonville; from Chicago to Crown Point; and from Cincinnati to Lawrenceburg, as well as to many other border towns in the state, to tie the knot posthaste. In 1877, the Hoosier marriage age of consent was 18 for women, 21 for men; 16 and 18 with parental consent, respectively. Couples could be legally married by judges, justices of the peace and certain types of Christian clergy without any waiting period, in contrast to neighboring states’ stringent statutes

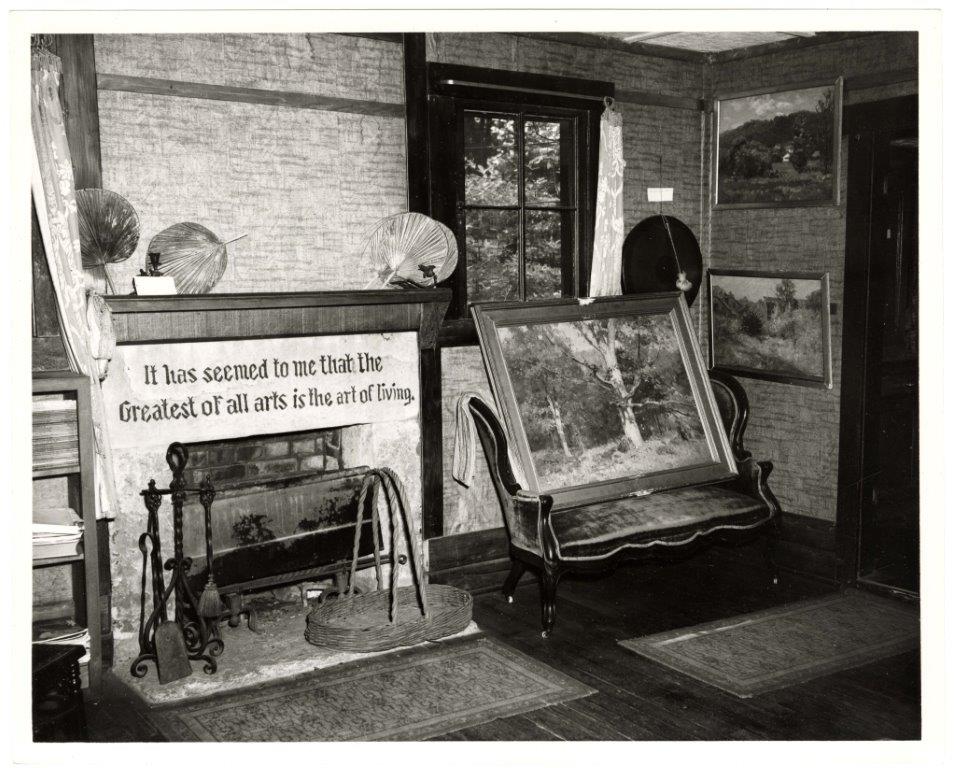

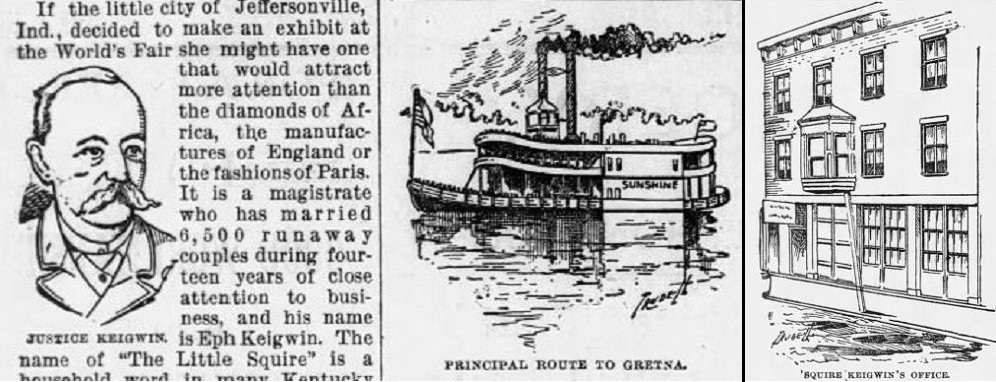

Squire Ephraim Keigwin – the first marrying squire of Jeffersonville, who married 9,000 couples during his career – opened his marriage parlor in 1877, complete with a boudoir for the bride to ready herself before the ceremony. Such premises often functioned like wedding chapels in Las Vegas today. The marriage parlors were generally open 24/7 and frequently offered services and amenities a betrothed couple might purchase, including rings, flowers, clothing, and sometimes, lodging for the wedding night.

Illustrations of Squire Keigwin, his office and the steamboat to Jeffersonville, 1893 / Daily Democrat (Topeka, KS)

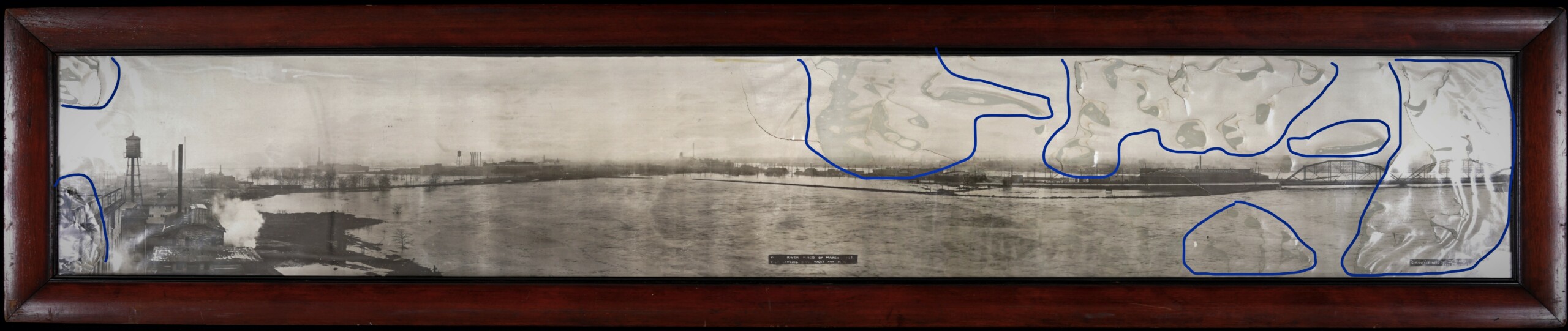

In the early days of its matrimonial trade, the Jeffersonville “marrying squires” would drum up business by meeting the steamships crossing the river from Louisville and offering their cards to lovestruck couples on the quay. As business boomed, the officiants began employing matrimonial agents, known as “runners,” “touts,” “steerers,” or most disturbingly, “bride grabbers,” to accost couples at the railroad station, ferry landing or courthouse and chivvy them to the marriage parlor of their employer. Runners, who also often engaged in perjury by swearing to the age of a stranger before the magistrate, were not well-loved by locals or visitors. In fact, rivalries between the runners of competing magistrates became so contentious that fights would erupt over hapless elopers as they stepped off the boat from Louisville. In 1899, Jeffersonville passed an ordinance making it illegal to work as a runner or to accept their services, but it did not appear curtail the practice, which spread to other Gretna Greens.

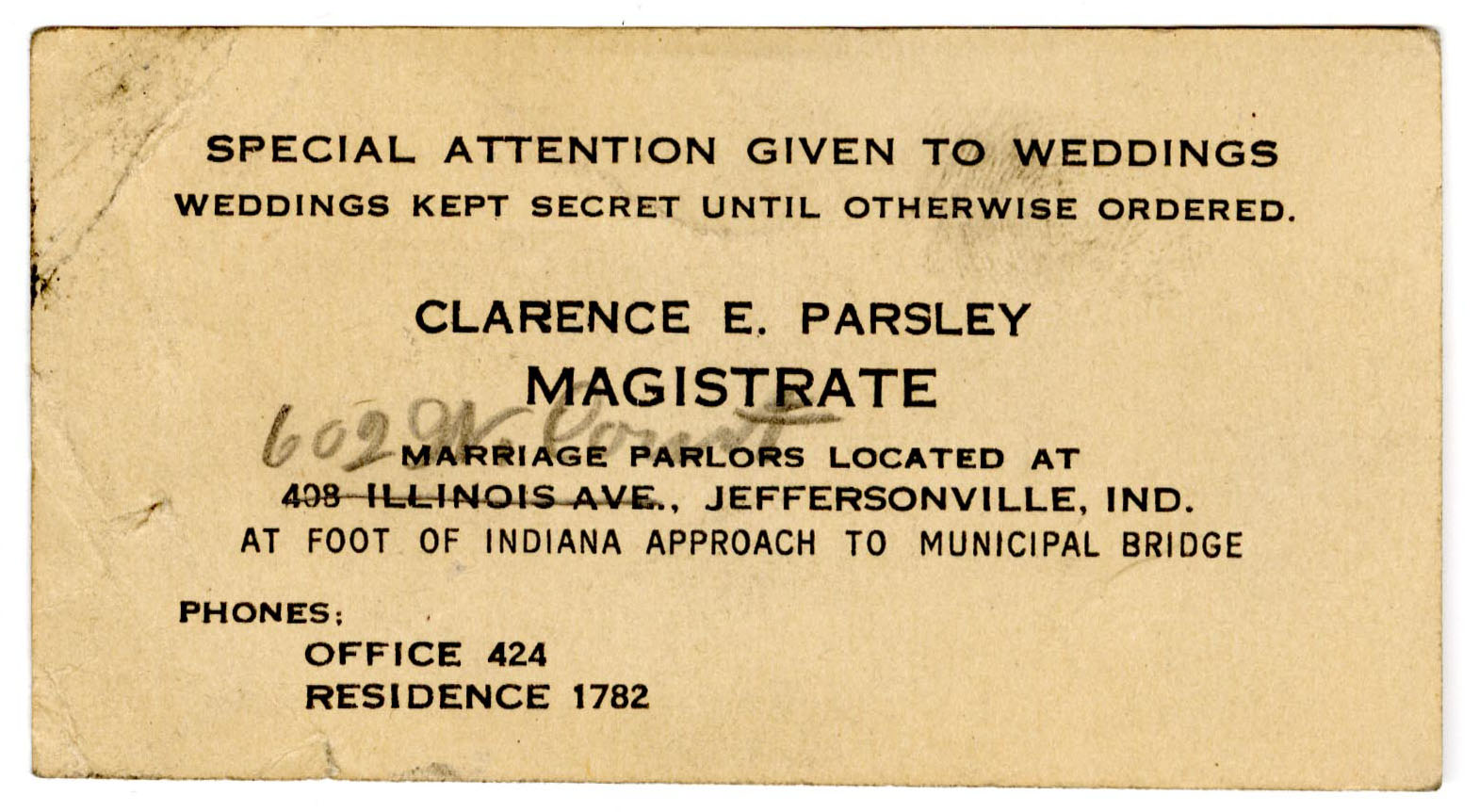

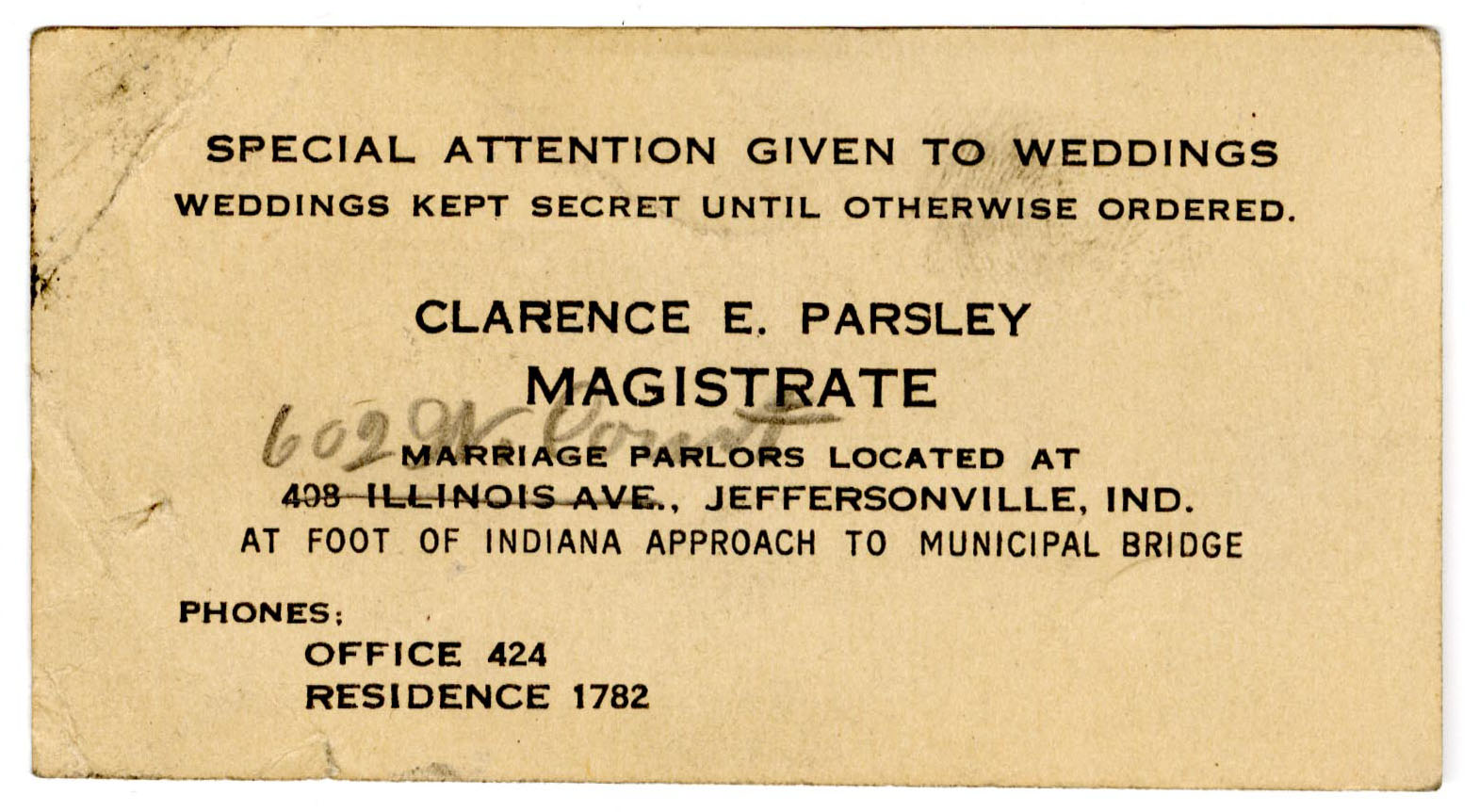

Business card of a “marrying squire” of Jeffersonville, ca. 1930 / Cejnar family collection, ISL

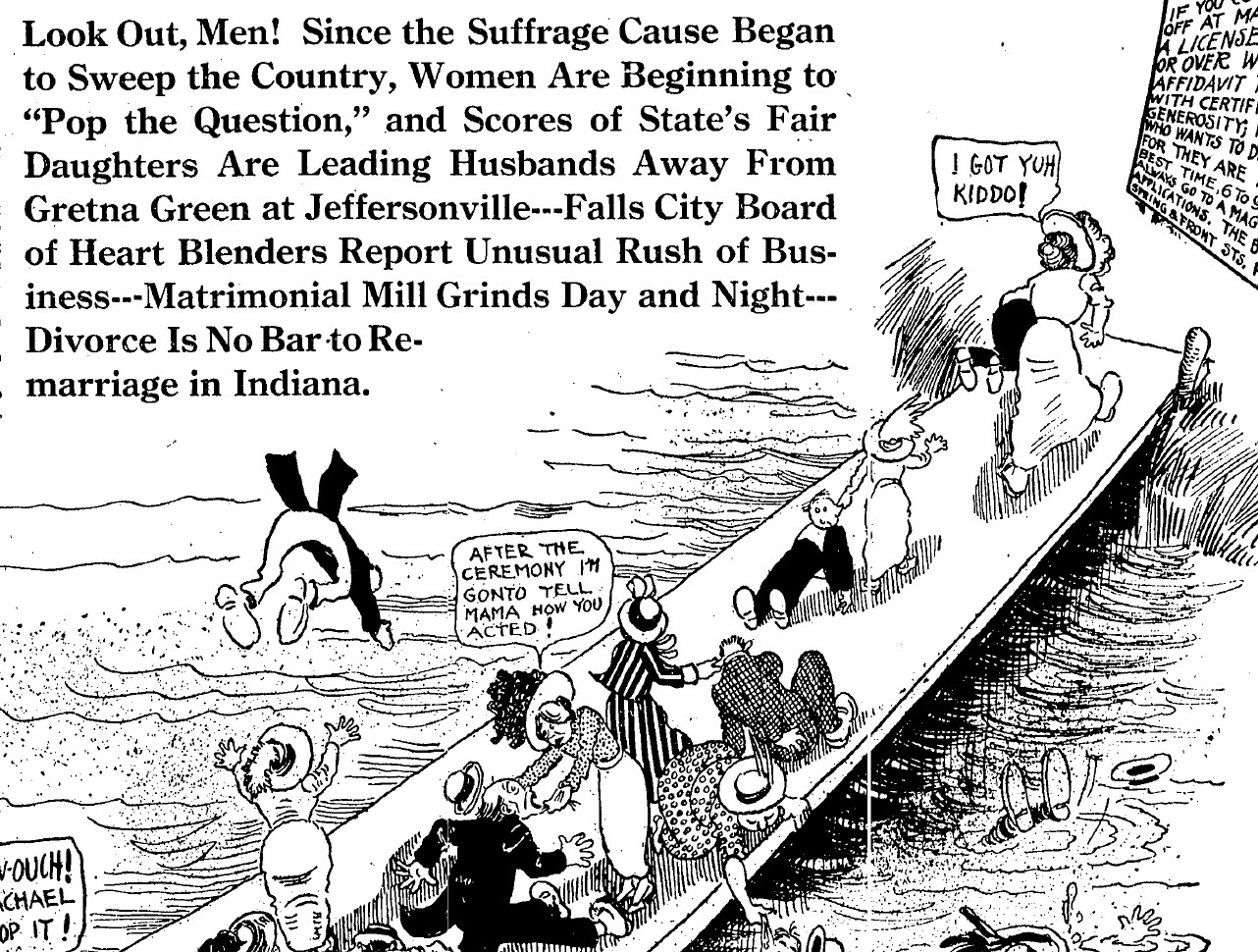

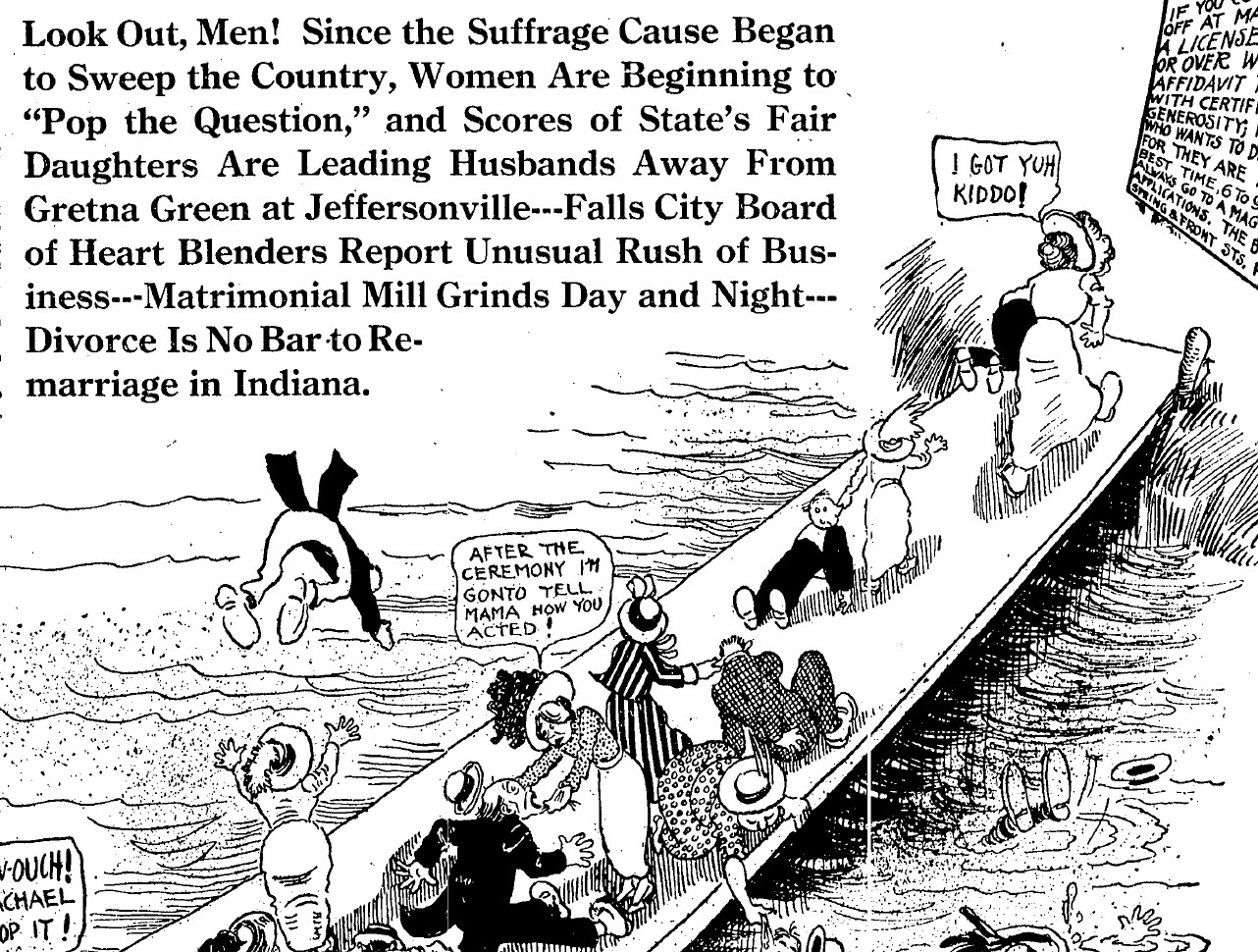

Some crafty matrimonial magistrates in southern Indiana even hired “pluggers” – women who would ride the steamboat from Kentucky identifying promised couples – to sidle up to potential brides and subtly endorse their employer’s place of business. As some ladies found employment through the marriage trade, women across the United States were seeking empowerment of another kind: the right to vote. As the women’s suffrage movement experienced a resurgence, the Hoosier matrimonial trade witnessed one of a different sort. In a rather sensational 1912 article in the Indianapolis Star, Jeffersonville magistrate James Keigwin claimed:

Every vote for suffrage is a vote for Dan Cupid… I have found many cases where the bride has taken the initiative. Just a few weeks ago a girl from Clark County, Indiana, entered my parlors, and after the ceremony confessed that she had not only proposed marriage to her blushing groom, but had purchased the railroad tickets and obtained the license, and then she produced her purse and handed me my record fee for 1912.

The accompanying cartoon paints a rather unflattering portrait of the assertive wives-to-be. It depicts the women as domineering figures seizing, dragging and even schlepping their unwilling, prospective grooms down the gangplank towards Jeffersonville’s altars. If said fiancés had not managed to jump overboard into the Ohio River, that is.

Part of a cartoon from Nov. 24, 1912 article in the Indianapolis Star.

During the Great Depression, the marriage business suffered like enterprises everywhere. In Jeffersonville, five justices of the peace – Benson R. Veasey, John M. Madden, Ryan Gannon, William Dorsey and Clarence Parsley – decided to join forces to cut costs. The quintet of “marrying squires” opted to combine their operations under one roof, opening a marriage parlor together in 1931. The new location was strategically close to the new municipal bridge from Louisville and while the parlor continued to operate every day at all hours, the magistrates no longer did, splitting shifts between them. By eliminating competition with the merger, the elopement entrepreneurs raised the price of a wedding from $2.50 to $3.00 and no longer needed to hire runners to drum up customers.

Five “marrying squires of Jeffersonville, ca. 1931 / Cejnar family collection, ISL

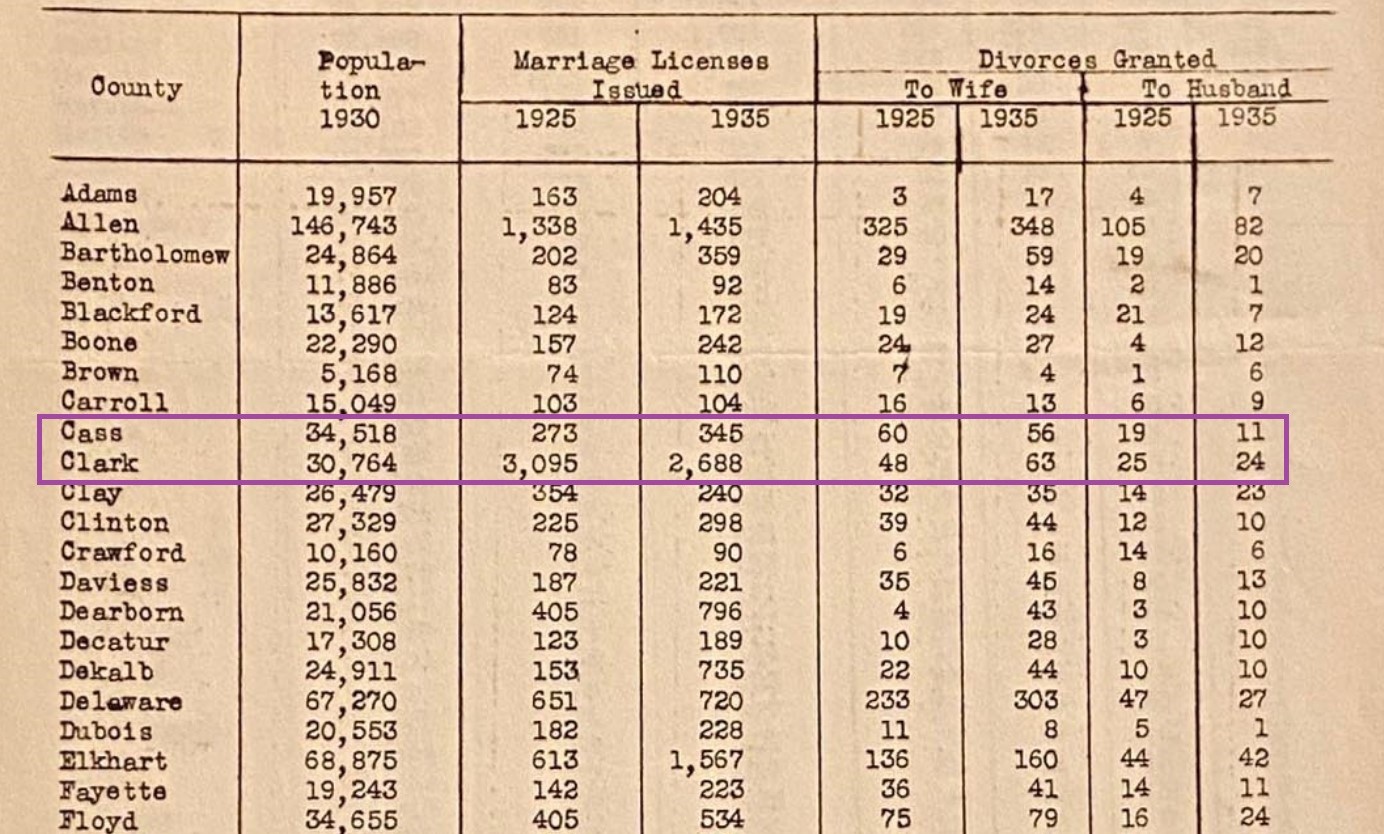

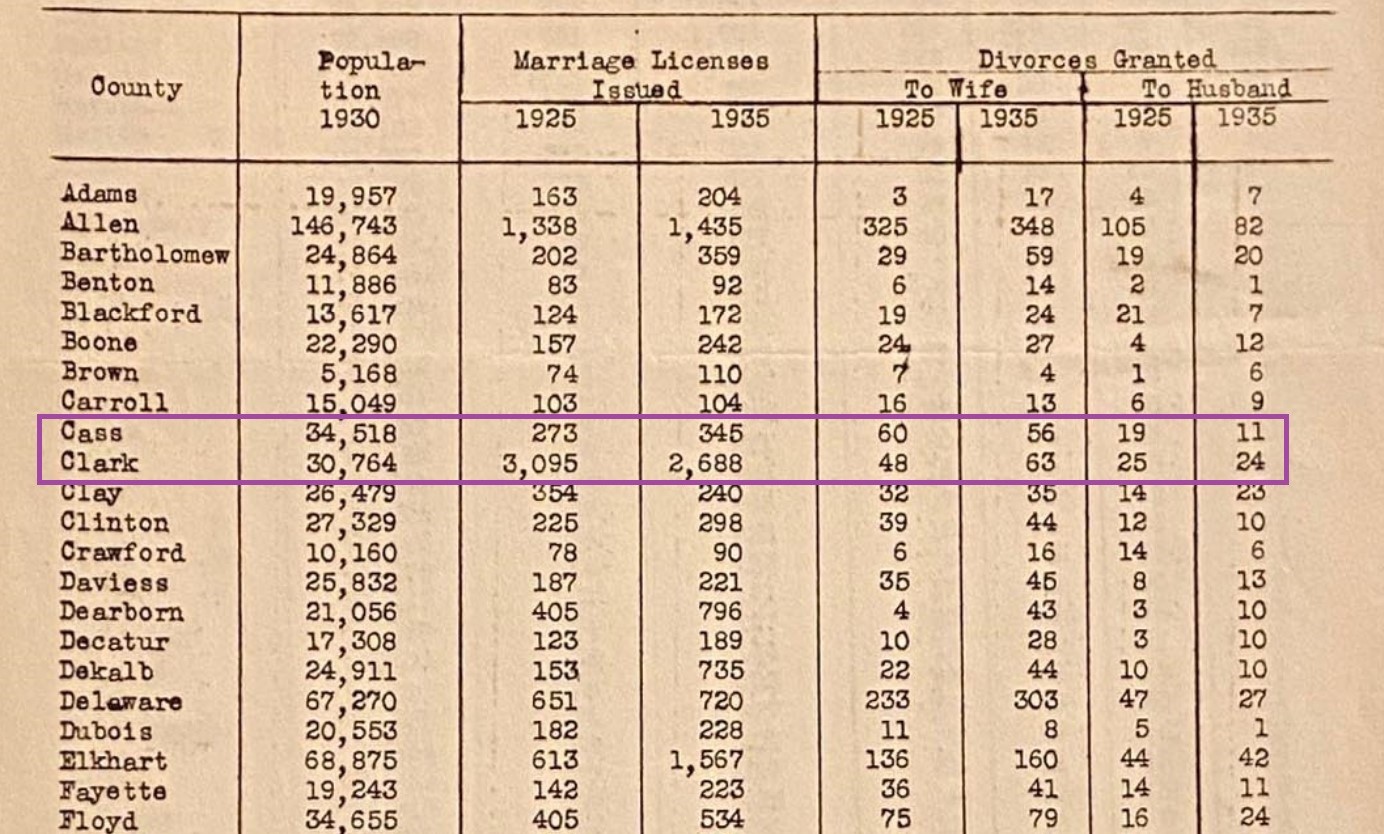

In southern Indiana, Jeffersonville’s matrimonial market still far outpaced the number of marriages in an average Hoosier town. During the 1920s and 1930s, Clark County annually issued between 2,000 and 3,500 marriage licenses, though this number may have been higher due to irregular reporting practices. Even during the early Depression years, the figures never dipped below 2,000. These figures stand in sharp contrast to Cass County’s statistics, as seen in the chart below, which had a higher population than Clark County in 1930 while its marriage licenses numbered in the low triple digits. In Lake County to the north, the Crown Point marriage mart outstripped Jeffersonville’s by 1916, never dipping below 4,000 marriage licenses into the 1960s, to the utter delight of its matrimonial business community.

Indiana League of Women Voters chart, 1937 / ISL

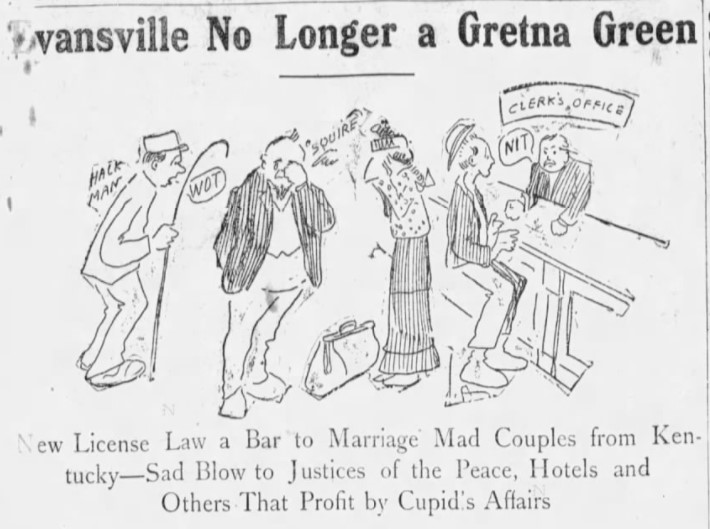

Not everyone was so enamored with Indiana’s Gretna Greens, however. Government officials, concerned citizens and religious leaders made numerous attempts over the decades to tighten up the state’s loose marriage statutes, concerned with sexual immorality, inebriation, high rates of divorce and sexually transmitted infections. Under pressure from irate parents of underage elopers, state legislators attempted to pass a bill in January 1895, which would require the endorsement of a resident property owner on license applications. They hoped the law would make runners think twice before committing perjury, but it failed to pass.

In 1901, Indiana Attorney General W. L. Taylor cracked down on marriage mills, particularly the ones in Jeffersonville, after a lawyer called attention to an old marriage license statute requiring the bride to reside within the county for 30 days before a license may be issued. Four years later, an Indiana state senator named Smith introduced a bill that would introduce a 10-day waiting period to stop elopements in 1905. It failed, but a subsequent eugenics marriage bill prohibiting people with mental illnesses, incurable or transmissible diseases, or epilepsy from marrying passed that same year. It was not repealed until 1977. The law required engaged couples to answer a long list of questions about themselves and their families before obtaining a license. The new requirements raised protests and alarm among entrepreneurs engaged in the marital trade, who predicted ruin.

Cartoon in the Evansville Courier and Press, 1905

As a result of these legal issues, matrimonial business in Indiana’s Gretna Greens lagged for a time during 1902-1906. In Clark County, the attorney general’s campaign against Jeffersonville’s marriage mills caused the number of marriage licenses issued to drop more than 50 percent in 1902. Between that and the new 1905 marriage law, the county’s numbers didn’t return to the status quo until 1907. In contrast, Lake County, which was not as popular a wedding destination as Clark County at the turn of the century, witnessed a dramatic increase in 1903. Crown Point and neighboring towns saw record numbers of weddings in 1906, on par with Clark County’s 1901 figures, thanks to Illinois’ own new marriage and divorce law of 1905.

In 1923, Representative Elizabeth Rainey of Indianapolis, the first woman officially elected and second to serve in the state legislature, introduced a bill to impose more rigorous conditions on the state’s marriage and divorce laws. The new statute would require a lengthy two-week waiting period after posting notice of the marriage and prohibit divorcés from remarrying for a year afterward. It did not pass. Outside Indiana, the judges and journalists of Chicago appeared to despise their neighboring state’s marriage mill. One such judge insisted he was “sick and tired of undoing midnight marriages” to the point of launching an investigation into nearby Gretna Greens like Crown Point in 1934. Of a similar mind, in 1936, the mayor of Crown Point made it illegal to marry between the hours of 9 p.m. and 8 a.m. or if the intended bride or bridegroom were intoxicated.

Celebrities taking advantage of the marriage mills only increased the popularity and infamy of the places. Crown Point was the popular elopement spot in the 20th century with many prominent individuals, including silent film star Rudolph Valentino and designer Natacha Rambova in 1923; boxer Kingfish Levinsky and fan dancer Roxana Sand in 1934; and starlet Jane Wyman and then actor Ronald Reagan in 1940. The added notoriety likely contributed to the eventual downfall of Indiana’s Gretna Greens.

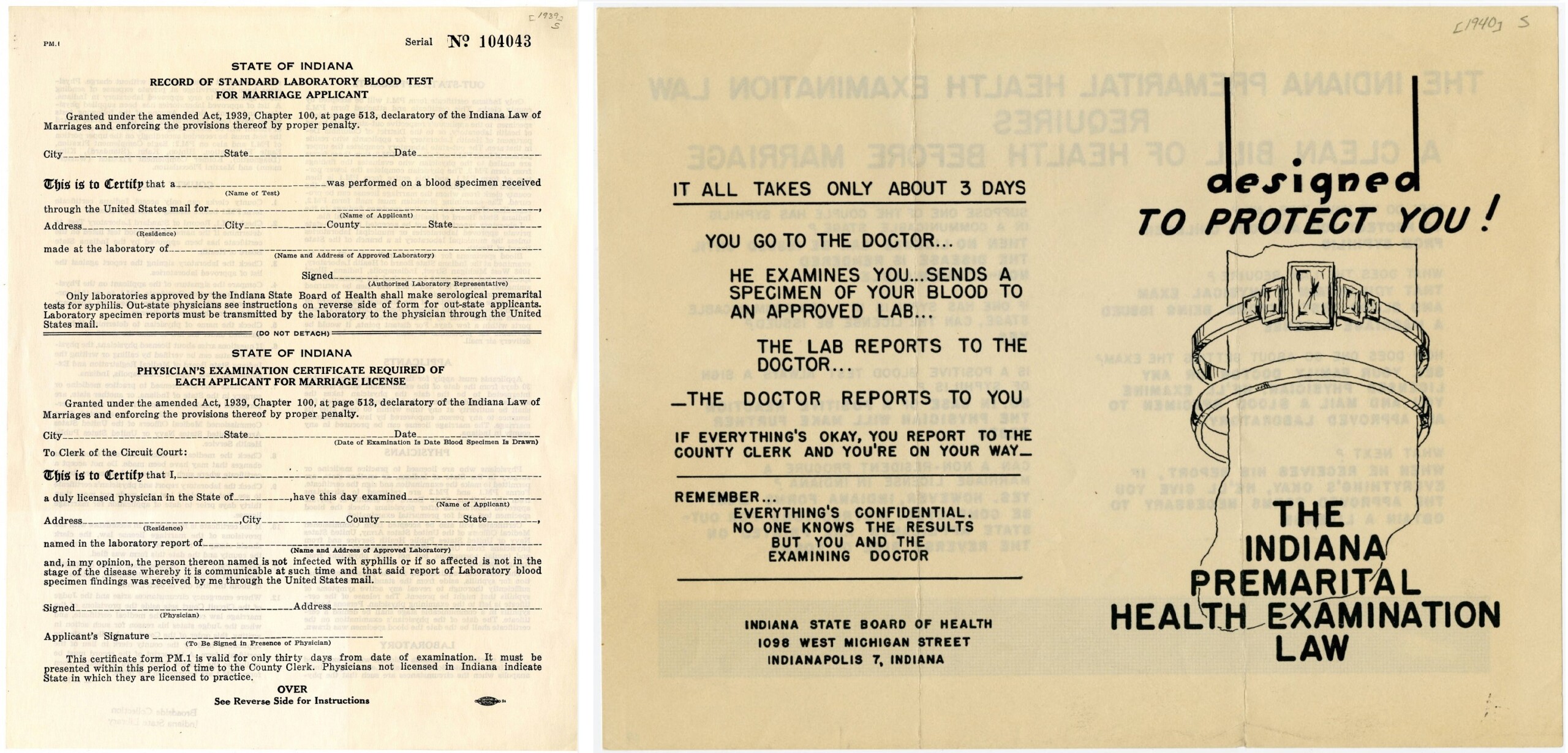

However, all statewide efforts to curtail ill-conceived weddings ultimately failed until 1938 when the Indiana Supreme Court upheld the 1852 statute requiring women to reside in the county for 30 days before being issued a marriage license from said county. The impetus behind the decision was Lake County prosecutor Fred Egan’s suit against county clerk George W. Sweigart to stop Gretna Green marriages in Crown Point. The following year, the Indiana General Assembly passed the Premarital Health Examination Law, requiring blood tests with mailed results certifying both participants were free of syphilis, going into effect March 1, 1940.

Thus ended the most lucrative era of marriage mills in Hoosier cities like Jeffersonville and Crown Point, but it did not stop the practice. County clerks found ways around these restrictions by taking a woman’s alleged local address, such as a hotel, at face value and providing rapid-delivery blood test results. By 1951, marriage mills like those in Lawrenceburg were doing a brisk business of 60 weddings on an average weekend.

Finally, on January 1, 1958, Indiana introduced its first mandatory waiting period, which required applicants to wait 3 days after laboratory testing to receive their results and obtain a marriage license. The three-day waiting period could still be waived if the couple brought test results from another state, as happened in the case of boxer Mohammed Ali and Sonji Roi on August 14, 1964 in Crown Point. A 1970 statewide referendum removed justices of the peace as constitutional officials, thus removing the final variable that had once allowed Indiana’s Gretna Greens to spring up and flourish a century earlier.

This blog post was written by Rare Books and Manuscripts librarian Brittany Kropf. For more information, contact the Rare Books and Manuscripts Division at 317-232-3671 or via “Ask-A-Librarian.”

Sources:

“Bill to Prevent Hasty Marriages.” Logansport (IN) Pharos-Tribune, Jan. 11, 1923. Newspapers.com.

Cavinder, Fred D. “Gretna Greens.” Indianapolis Star, Feb. 14, 1988. ProQuest.

Cejnar family collection, Rare Books and Manuscripts, Indiana State Library.

Crosnier de Varigny, Charles Victor. The Women of the United States. Translated by Arabella Ward. New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1895.

“Crown Point’s Marriage Business to Close Up Shop.” Kokomo (IN) Tribune, Jan. 12, 1938. Newspapers.com.

“Evansville No Longer a Gretna Green.” Evansville (IN) Courier and Press, April 30, 1905. Newspapers.com.

“Gretna Green Bill.” Indianapolis Journal, Jan. 22, 1895. Newspapers.com.

“Hasty Marriages End Here March 1.” Garrett (IN) Clipper, Jan. 22, 1940. Newspapers.com.

Indiana League of Women Voters. “A Chart Showing Increase or Decrease of Marriages and Divorces in Indiana.” Indianapolis: Indiana League of Women Voters, 1937.

Indiana State Board of Health. Indiana Marriages, 1962-1965, with Some Data from Other Years Since 1900. Indianapolis: Indiana State Board of Health, 1967.

“Join in Campaign Against Crown Point Marriage Mill.” Garrett (IN) Clipper, Oct. 11, 1937. Newspapers.com.

“Marriage Mill Breaks Record.” Hammond (IN) Times, Dec. 31, 1906. Newspapers.com.

“’Marrying Squires’ Link Own Hands When Slump Hits Matrimonial Mart.” Daily Mail (Hagerstown, MD), Jan. 24, 1931. Newspapers.com.

“Matrimonial Runners.” Bedford (IN) Times-Mail, June 17, 1908. Newspapers.com.

“Midnight Marriages.” Tipton (IN) Daily Tribune, Oct. 6, 1934. Newspapers.com.

Mitchell, Dawn. “Indiana Was a Scandalous Marriage Mill and Valentino Took Advantage.” IndyStar, July 4, 2019.

“New Law Effective; Weddings Prevented.” The Inter Ocean (Chicago, IL), July 2, 1905. Newspapers.com.

“Our Gretna Green.” Logansport (IN) Pharos-Tribune, Feb. 1, 1893. Newspapers.com.

Pierce-Krull family papers, Rare Books and Manuscripts, Indiana State Library.

Small broadsides collection, Rare Books and Manuscripts, Indiana State Library.

“Valentine Marries Winifred Hudnut the Second Time.” The Republic (Columbus, IN), March 15, 1923. Newspapers.com.

The digital archive debuted in October of 2019, with the first batch of poems available Sept. 1, 2020. The project was the brainchild of former 2018-19 Indiana Poet Laureate Adrian Matejka – now editor of Poetry magazine – and intended to celebrate, capture and preserve the works of Indiana’s diverse poets for future generations. It is a collaboration between the Indiana Poet Laureate, the Indiana Arts Commission and the Indiana State Library.

The digital archive debuted in October of 2019, with the first batch of poems available Sept. 1, 2020. The project was the brainchild of former 2018-19 Indiana Poet Laureate Adrian Matejka – now editor of Poetry magazine – and intended to celebrate, capture and preserve the works of Indiana’s diverse poets for future generations. It is a collaboration between the Indiana Poet Laureate, the Indiana Arts Commission and the Indiana State Library.