War Department General Order 143 officially created the Bureau of Colored Troops on May 22, 1863. Maj. Charles Foster was put in charge of recruitment, training, placement of troops and officer selection.[1] At the beginning of the war, offers to recruit troops of color had been refused, but after 1862 and the Emancipation Proclamation, liberation of enslaved people became a stronger driving force of the war.[2] Allowing African Americans to enlist also helped states meet their enlistment quotas, which became more difficult to do as the war went on. Gov. Oliver P. Morton wavered on whether to recruit black troops in Indiana for political reasons – one of the main risks being that as a border state the outcome could result in losing Union support from Hoosiers in the southern part of the state.[3] Prior to the official order, it wasn’t uncommon for black men to leave their home states to enlist in states where they could fight.[4] On Nov. 30, 1863, Morton finally gave the order to form a regiment of black troops in Indiana, one of the few black regiments formed in a Northern state, the 28th United States Colored Troops was born.[5]

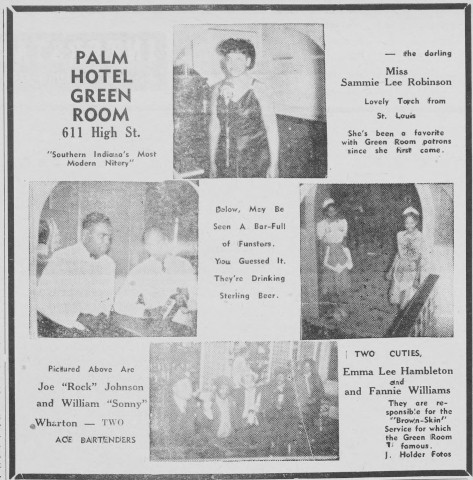

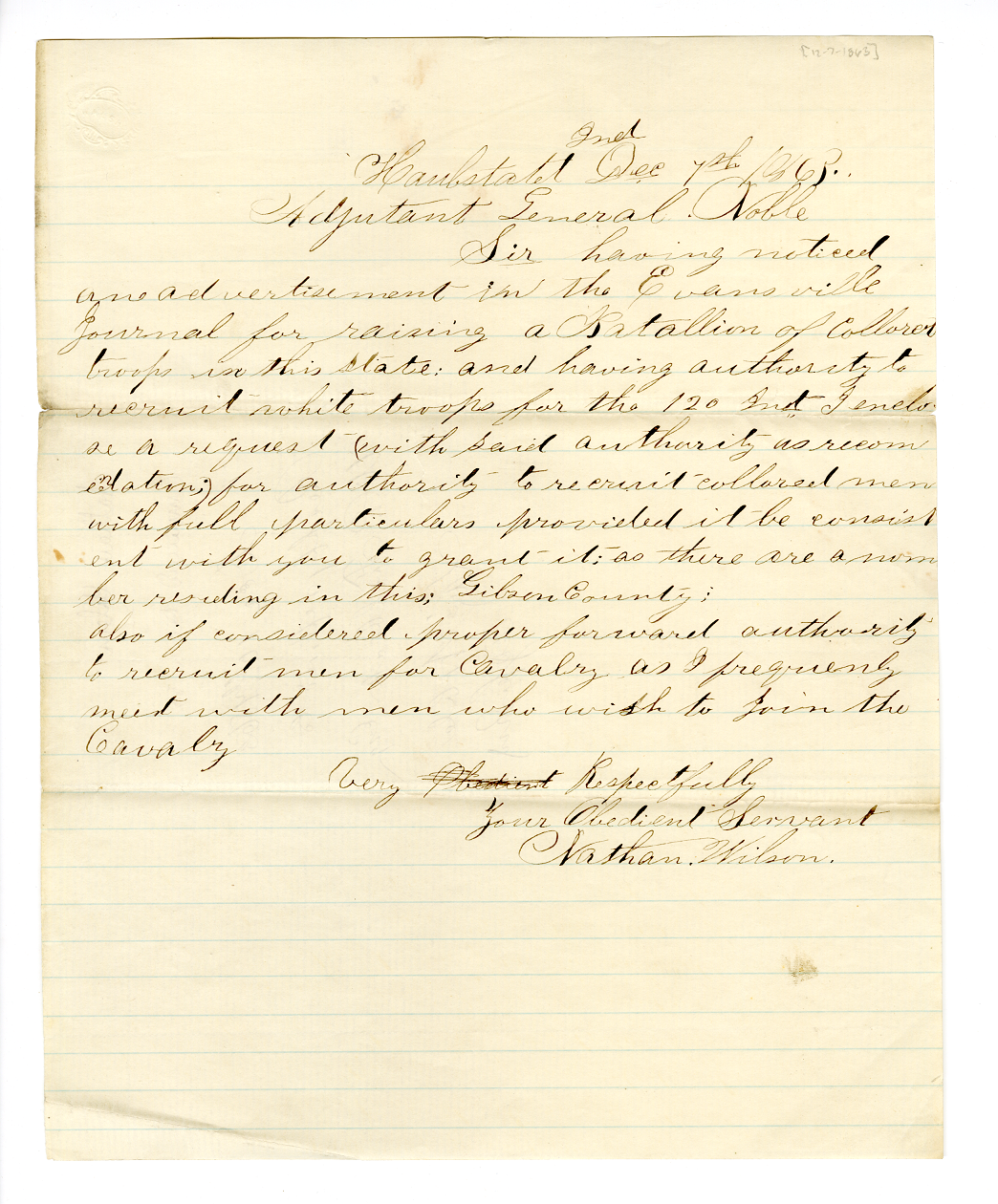

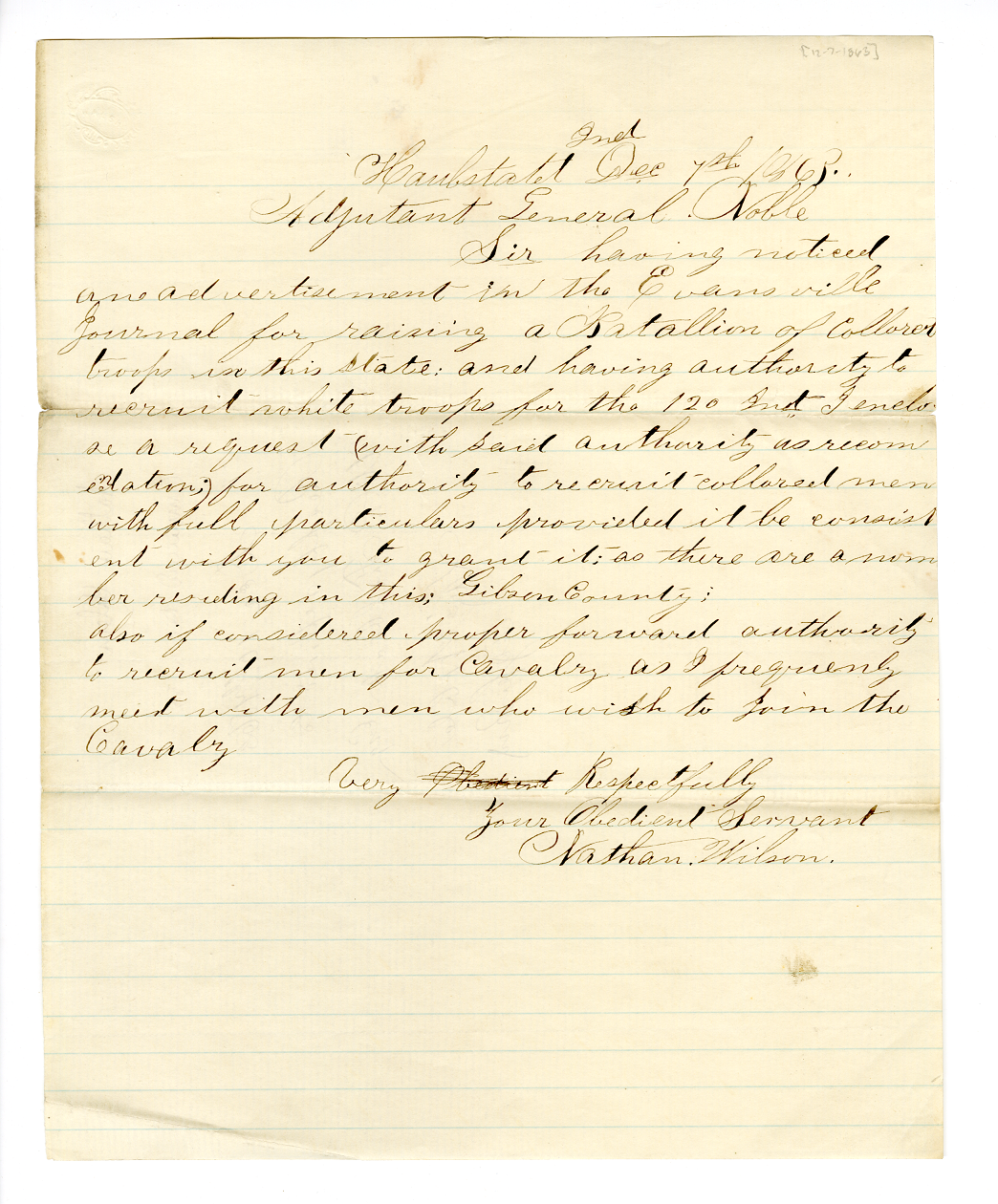

Nathan Wilson letter to Adj. Gen. Lazarus Noble, Dec. 7, 1863, L548 Anna W. Wright collection, Rare Books and Manuscripts, Indiana State Library.

The 28th USCT departed Indianapolis for Virginia in April of 1864 to a positive reception from the local press. They were assigned to the Fourth Division of the Ninth Corps – part of the Army of the Potomac – under Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside and commanded by Gen. Edward Ferrero.[6] From there, they were involved in some of the most famous events of the Civil War, including the Petersburg Campaign, Battle of the Crater and the fall of Richmond. On their way toward Petersburg, they were involved with a number of skirmishes which allowed them the chance to prove their mettle amongst the other troops, both boosting morale and reputation. In summer of 1864, the Army of the Potomac planned another siege on Petersburg with most of the existing troops exhausted from weeks on end of combat. This situation left the Fourth Division in a position to lead a charge that could potentially end the war. It was also, unfortunately, the ill-fated Battle of the Crater.[7]

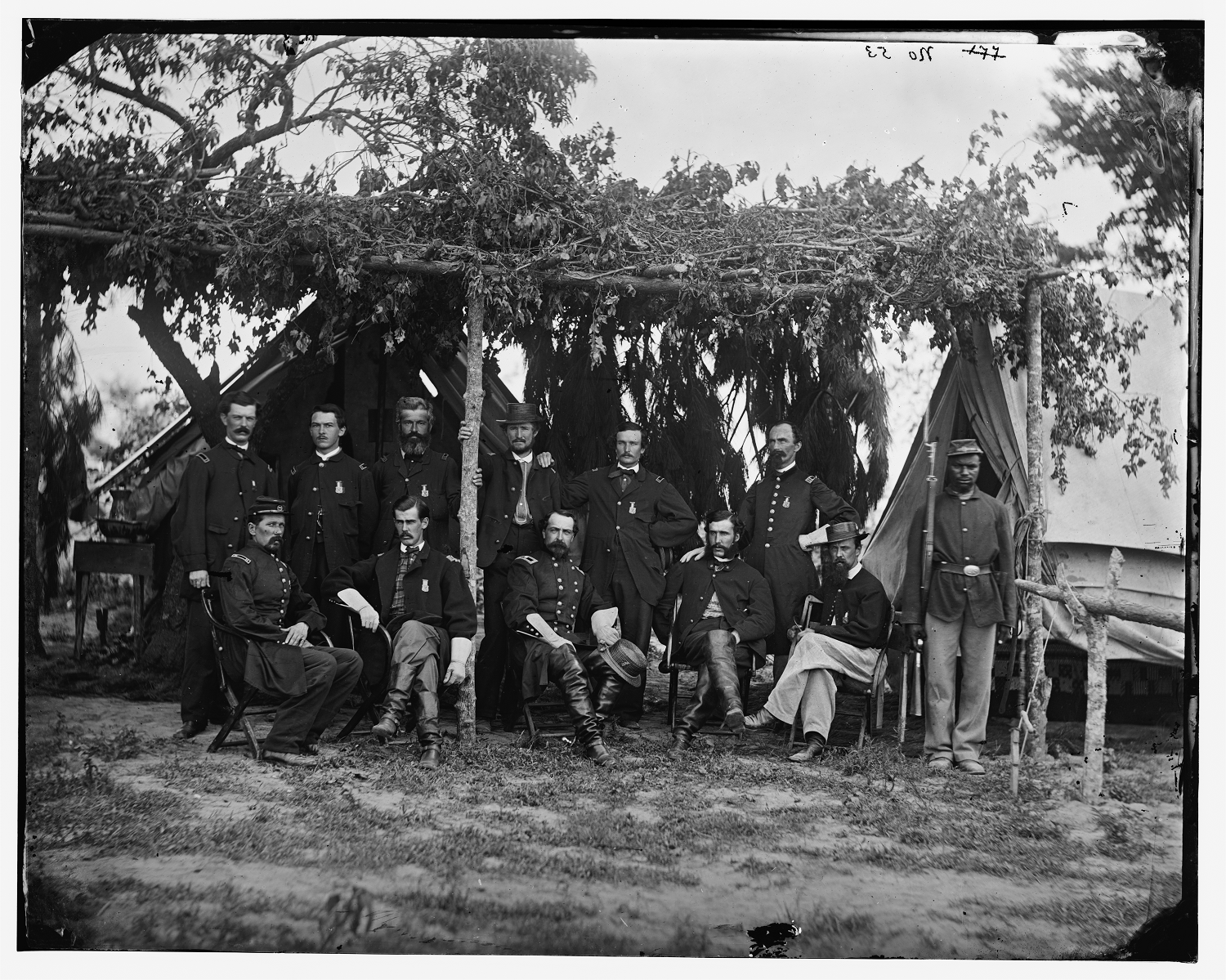

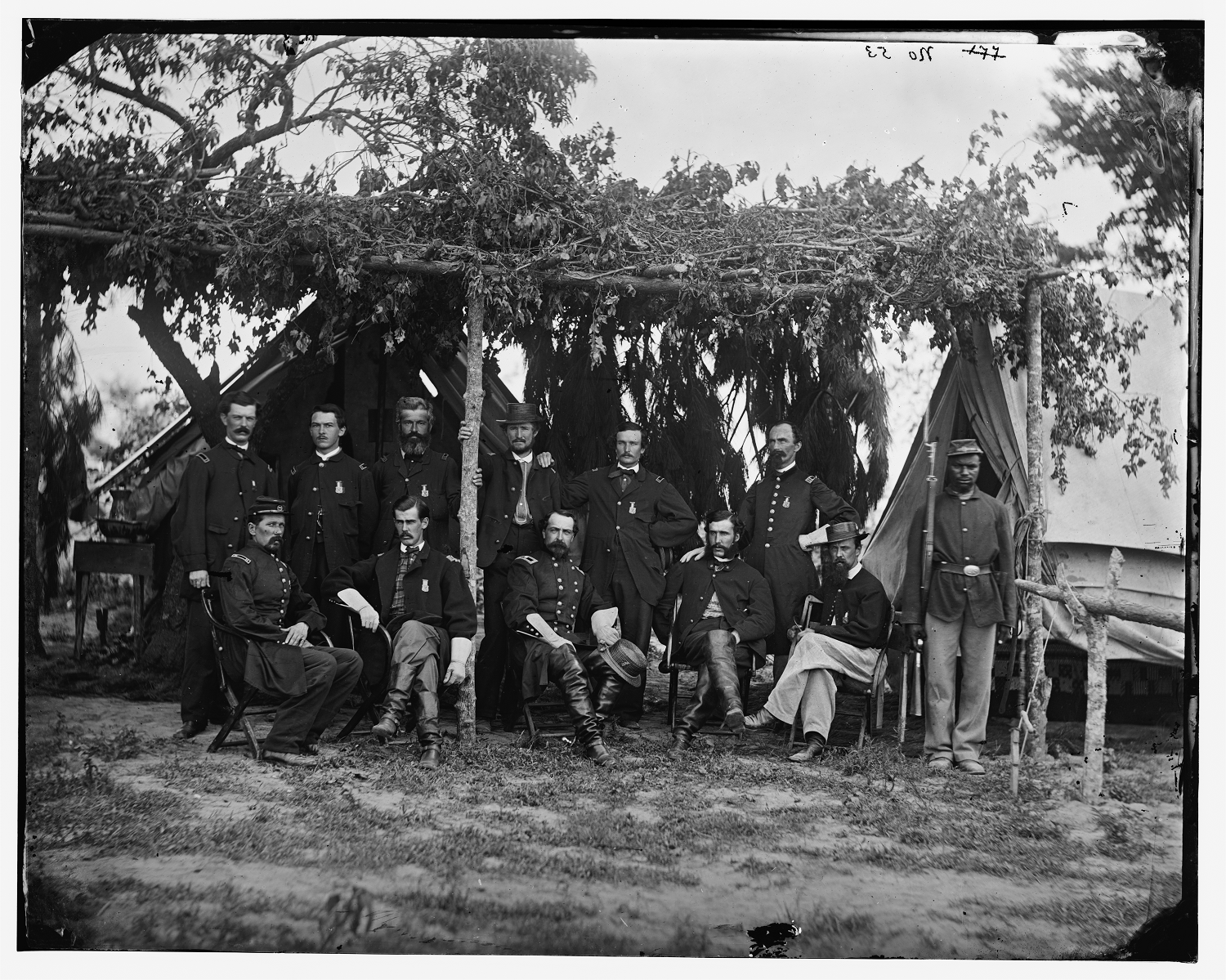

Petersburg, Virginia. Gen. Edward Ferrero and staff photograph. 1864, Sept. From Library of Congress: Civil War photographs, 1861-1865. Accessed Feb. 27, 2020.

The Battle of the Crater was supposed to clear the road to Richmond and the end of the War. The Fourth Division had trained for weeks while others dug a mine shaft underneath a Confederate fort where explosives would be utilized to commence the battle. Less than 24 hours before the anticipated explosion, Maj. Gen. George Meade told Burnside to have one of his white divisions lead the charge instead. This decision was backed up by Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant.[8] The morning of July 30, 1864 was riddled with snafus including communication errors, delays and issues lighting the fuse on the explosives. By the time the Fourth Division entered battle, two hours after it had commenced, there was a veritable bloodbath in the crater that was left behind by the explosion. Leading Union troops were unable to climb out of the crater. The black troops charged forth gallantly into the battle with valor that none could deny, but met a storm of bullets from Confederate troops and few white soldiers were willing or able to back them up.[9] With African American troops officially part of Union forces, the Confederate soldiers fought with increased fury and atrociousness. Massacre of black soldiers trying to surrender was commonplace and very few black soldiers were taken prisoner.[10] Reports of the losses of the 28th USCT from the Battle of the Crater vary, but have been noted to be between 40-50%, not including officers.[11] Afterwards, there was a Court of Inquiry looking into the calamity at the Battle of the Crater and Burnside was relieved of command. Racism is frequently brought up as a primary factor in the Fourth Division being re-assigned at the last minute before the Battle of the Crater. Burnside was the only leader who had faith that the black troops could succeed at the time. In the Court of Inquiry, blame was even placed on the Fourth Division for the chaos of the Battle of the Crater. It is clear that the USCT were never fully accepted as brothers in arms during the Civil War.[12]

“What Eight Thousand Pounds of Powder Did” photograph. In Civil War, through the camera. McKinlay, c. 1912, p. 193.

After the Battle of the Crater, the 28th USCT was assigned to the Army of the James – as part of the 25th Corps they helped make up the largest formation of black troops in American history.[13] They weren’t put in active service until the spring of 1865 when they were moved to the front lines between Petersburg and Richmond.[14] On April 1, 1865, the Confederate government fled the city of Richmond. With the Army of Northern Virginia defeated, the road was clear for Union troops to march into the city. The 28th USCT advanced and was one of the first to enter Richmond at the end of the war.[15] After a brief stint in Texas, they were mustered out of service on Nov. 8, 1865.

This blog post was written by Lauren Patton, Rare Books and Manuscripts librarian, Indiana State Library. For more information, contact the Indiana State Library at 317-232-3678 or “Ask-A-Librarian.”

[1] Moore, Wilma L., “The Trail Brothers and their Civil War Service in the 28th USCT”, Indiana Historical Bureau. https://www.in.gov/history/4063.htm. Accessed February 13, 2020.

[2] Forstchen, William R., “The 28th United States Colored Troops: Indiana’s African-Americans go to War, 1863-1865”, Ph.D., diss., (Purdue University, 1994), p. 21, 36.

[3] Forstchen, p. 21.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid., p. 8, 42.

[6] Ibid., p. 9.

[7] Ibid., p. 99.

[8] Williams, George W. A History of the Negro Troops in the War of the Rebellion, 1861-1865. New York: Harper, 1888, p. 244-245.

[9] Forstchen, p. 129.

[10] Ibid., p. 132.

[11] Williams, p. 250 and Forstchen, p. 146.

[12] Forstchen, p. 161-162.

[13] Ibid, p. 10.

[14] Ibid., p. 193.

[15] Ibid.