Librarians in the Indiana Division of the Indiana State Library frequently get questions on how to find historical information about an old building or where to find the location of an old business. There are several online resources that we usually check first: fire insurance maps, online newspapers and city directories. The search strategy can take different angles, depending on what information is already known and what information is sought. It is always helpful to have a general time range in mind before starting any search.

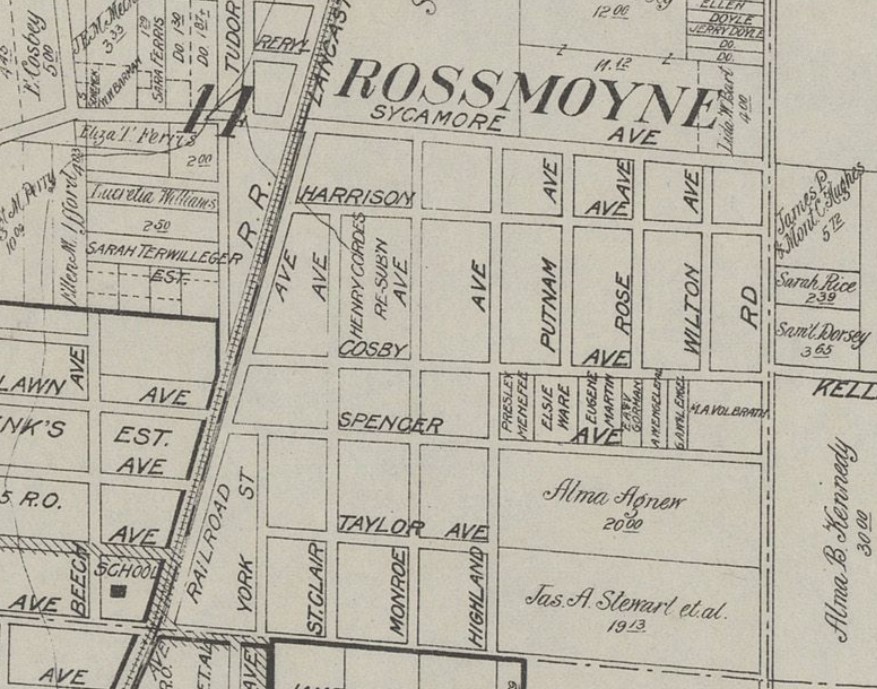

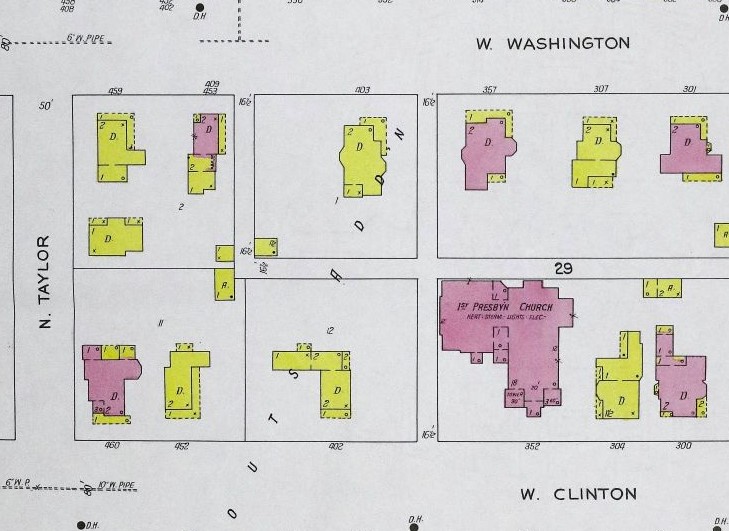

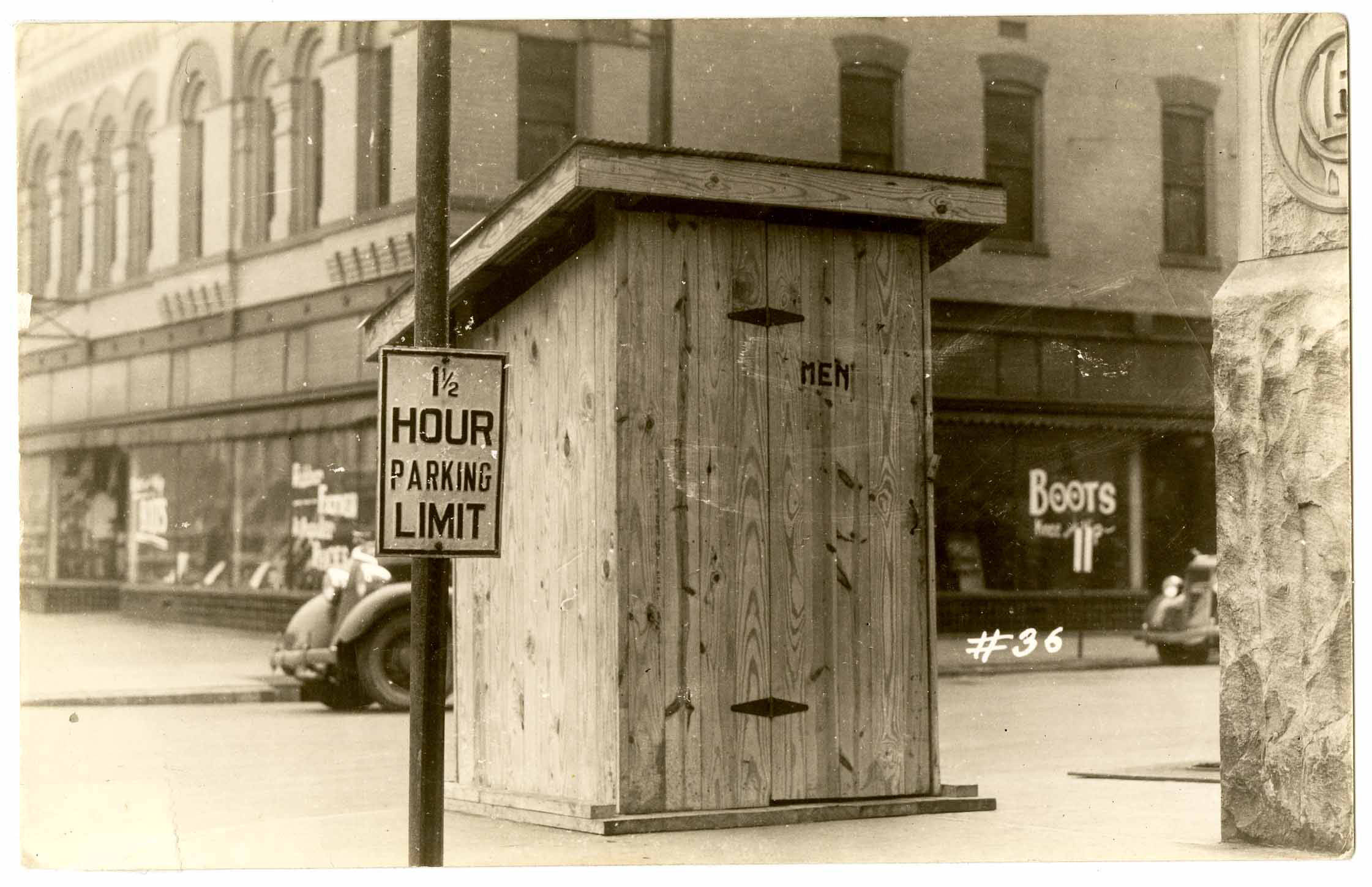

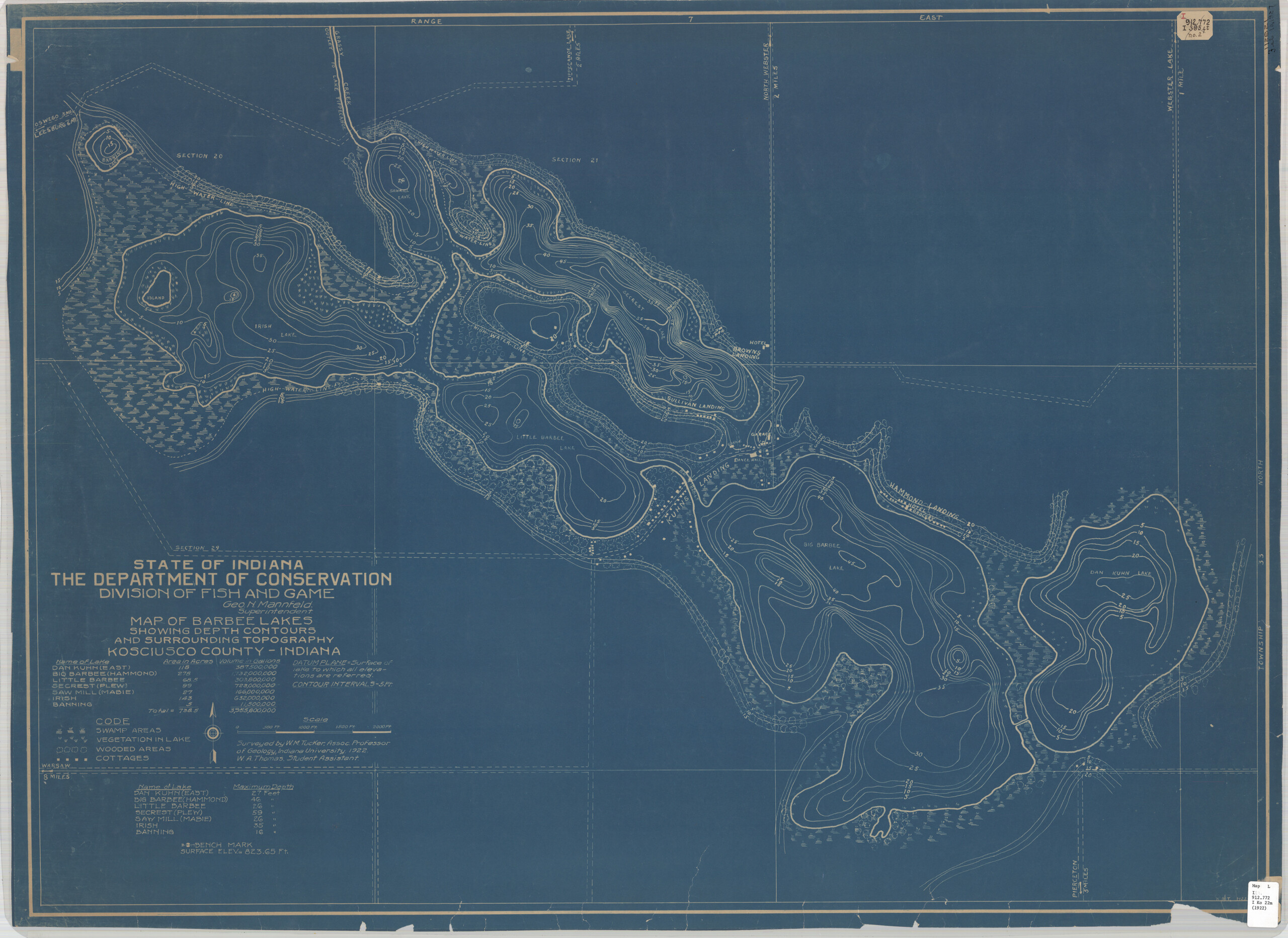

Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps can prove useful. Fire insurance companies created these detailed, building-by-building maps of most urban areas to assess fire risk for insurance pricing. Many Indiana towns and cities were surveyed from the late 1880s through the mid-1950s and have maps available. An excellent free source of pre-1923 digitized Sanborn maps around Indiana is the Indiana Spatial Data Portal and its new public viewing interface. The Indiana State Library also subscribes to the Indiana maps within the Fire Insurance Maps Online Database, with access available within the building. The Indiana Division also has Sanborn maps on microfilm that includes years after 1923, just check with the staff at the second floor information desk.

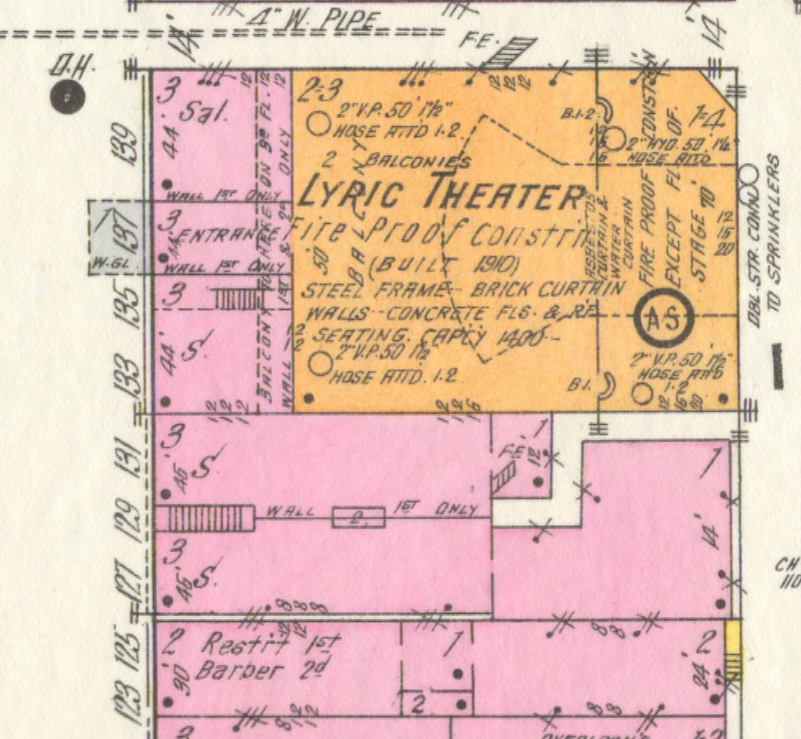

Additional years of online Sanborn maps of Indianapolis are available through the Indianapolis Sanborn and Baist (IUPUI) Digital Collection. Thanks to a special project, the text descriptions (metadata) of each map sheet are searchable by keyword, landmark type and intersecting street names. For example, a keyword search for “Lyric” yields six results including Indianapolis Sanborn Map #37, 1915 that shows the location of the Lyric Theater along Illinois Street.

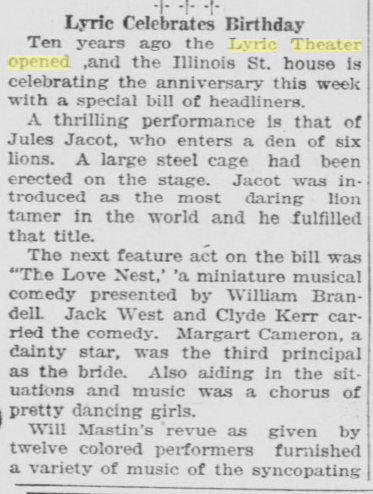

Hoosier State Chronicles is an excellent online collection of newspapers from around Indiana, and the best thing about them is the text-searching capabilities. Using quotation marks around search phrases can yield very precise results. To discover when the Indianapolis Lyric Theater first opened its doors, search for a phrase that might be included in an article, such as “Lyric Theater opened.” The best result from the Oct. 10, 1922 issue of the Indianapolis Times tells of the theater’s 10th anniversary, placing its opening year of 1912.

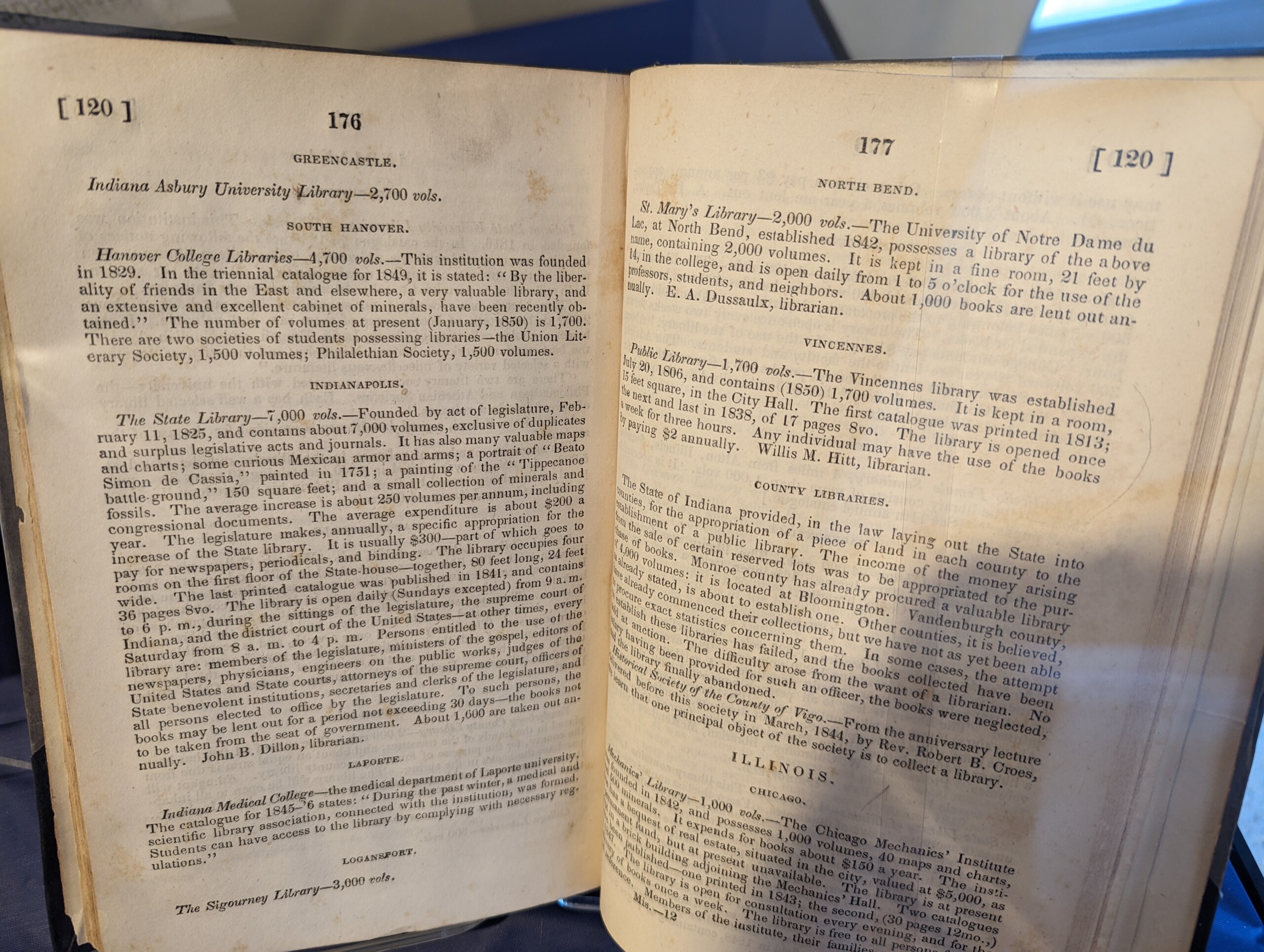

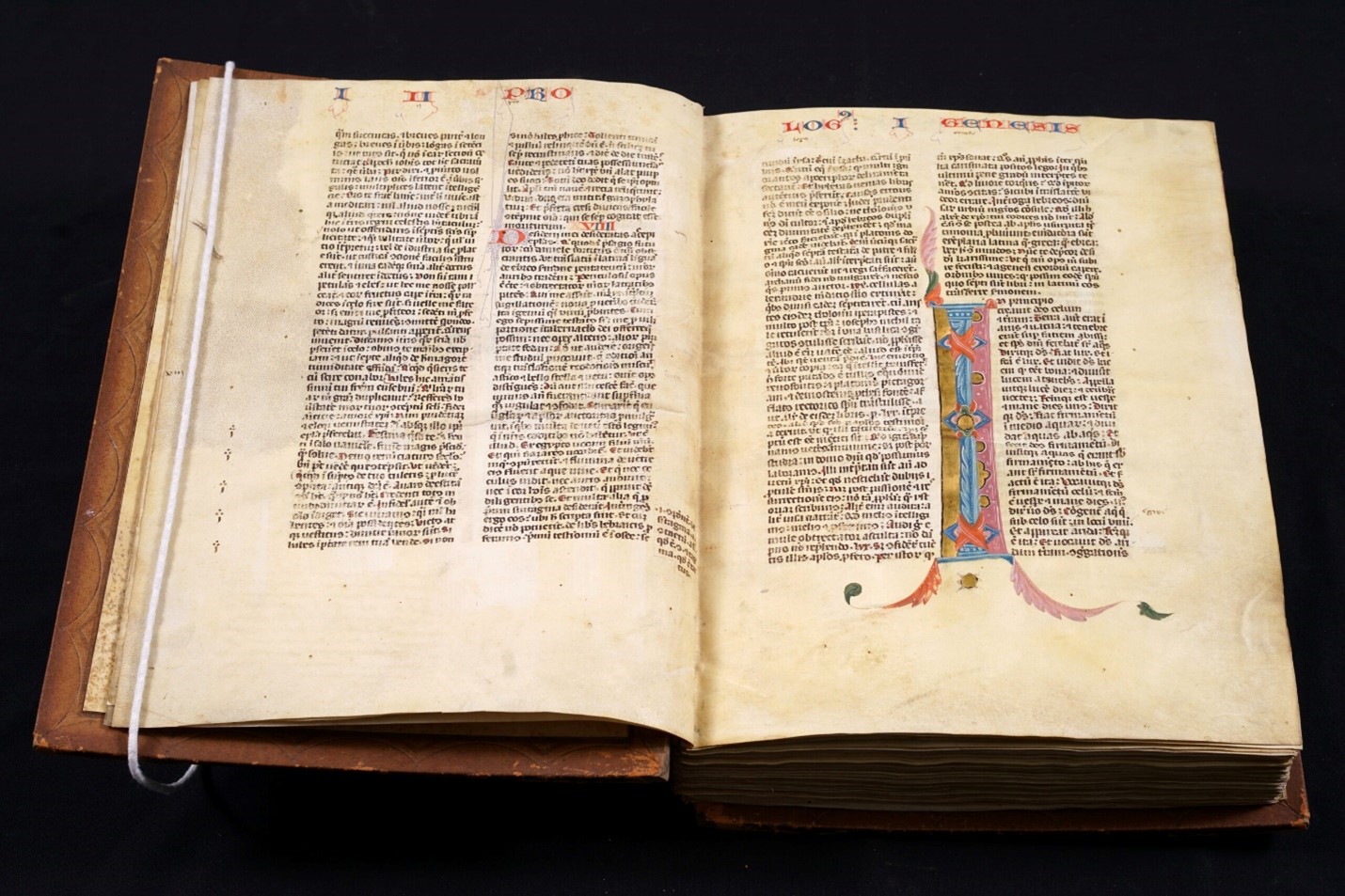

Why not try searching the city directory? Leafing through the pages can be tedious, but many directories have been digitized for access and preservation. Large cities tend to have earlier years and long runs of directories that were published. The Evansville City Directory online collection contains digitized and searchable volumes hosted through the Evansville Vanderburgh County Public Library. Other organizations such as the Allen County Genealogical Society maintain a guide with links to all known digitized copies of Fort Wayne and Allen County directories. More online copies of historical directories for Indiana cities can be found in Ancestry Library edition, Internet Archive, Google Books and Indiana Memory.

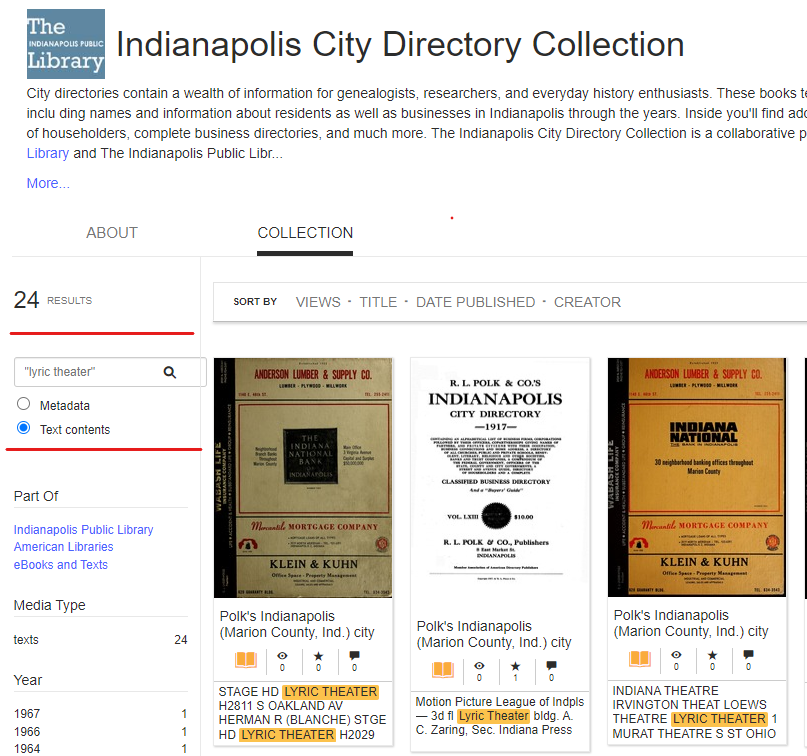

The Indianapolis City Directory Collection is hosted on Internet Archive. It is possible to narrow down and choose a single year’s volume and search the text. The entire set of 149 volumes can also be searched by toggling the search option “Text contents.” Keeping up the search for the “Lyric Theater” in Indianapolis, the results might yield advertisements and even names of theater employees who appear in the residential listings. This search produced 24 results.

While it may take some trial and error to find that perfect phrase for searching by street address, studying how the addresses are shown on the pages can help. Also check for abbreviations used by the publisher. Don’t search for “2234 North Main Street” when the directory lists the address as “2234 N Main.” Keep in mind that the entries might change format over the decades, so the search phrase may need to be adjusted to catch all variations. Business storefronts may expand or shrink, and the Post Office may assign a slightly different address number. Cities and towns have been known to rename their streets too, so use the directories in conjunction with Sanborn maps or other street maps.

Once the maps, newspapers and directories are searched, it doesn’t hurt to go back with any new information and search it all again. As always, the librarians can assist researchers getting started or needing additional guidance with online and print resources. The Indiana Division of the Indiana State Library collects county and city histories, maps, city directories and newspapers from all 92 counties. Let us know how we can help!

This blog post was written by Indiana Division librarian Andrea Glenn. For more information call (317) 232-3670 or “Ask-A-Librarian”.