Did you know that as a registered borrower at an Indiana public library, you may have access to the collections of over 170 other public libraries? This is possible through the reciprocal borrowing program, one of the best kept secrets in Indiana public libraries. This blog post will share information about reciprocal borrowing, as well as other options for borrowing from other libraries.

Statewide Reciprocal Borrowing Covenant

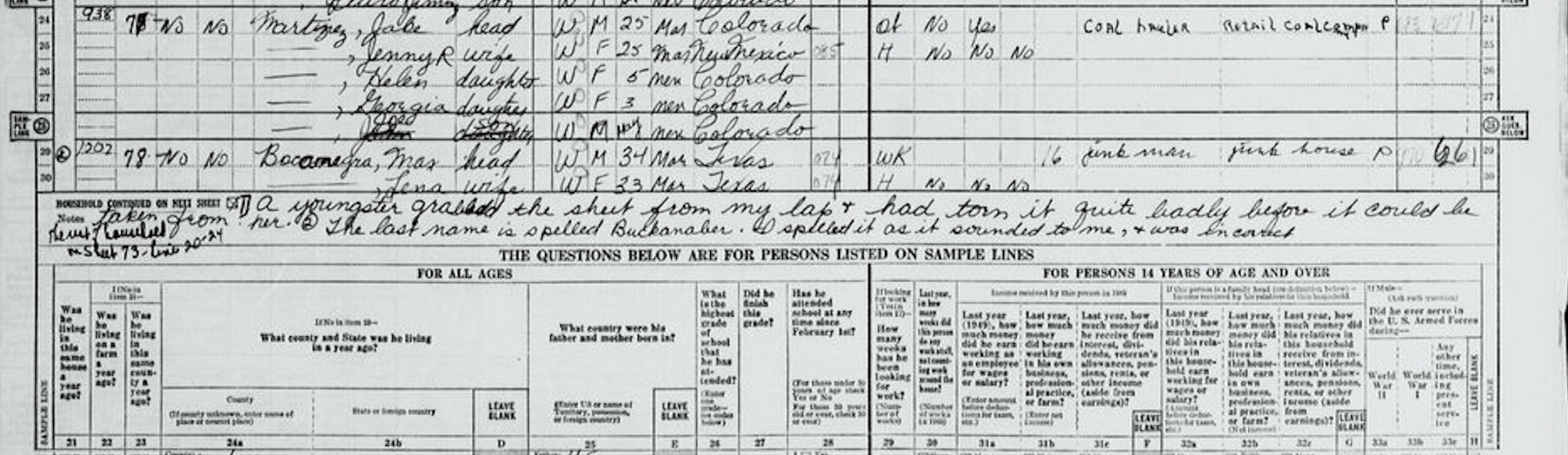

While “statewide” is in the name, we will add a disclaimer that not all 236 of the state’s public libraries districts are participants. However, there are 172 currently participating districts all over the state. If you are a patron of a participating library, you can show your home library card, in person, at any of the other participating libraries and receive a borrower’s card with reciprocal borrowing privileges. There is no cost to participate in this service unless you incur late or lost item fees for items borrowed. Please check with the circulation staff at the library you are visiting for details about what is available to reciprocal patrons. Some services, like access to e-books and interlibrary loan, may not be available to reciprocal patrons per local policy.

Local Reciprocal Borrowing Covenants

Some library districts have opted to partner only with nearby districts to extend borrowing privileges to the patrons of neighboring libraries. These may include county-wide agreements or agreements between libraries that are close in proximity to each other. While the Indiana State Library collects information on which libraries are participating in such agreements, the circulation staff at your library can give you the most up to date information about whether or not they have a reciprocal agreement with other local libraries. There is no cost to participate in this service, unless you incur late or lost item fees.

Public Library Access Card

Public Library Access Card

If your library is not participating in either of these reciprocal agreements, you can purchase access to all of the 236 public libraries in the state through the Public Library Access Card program. With a PLAC card, a borrower can visit any of the state’s 236 public libraries and show their home library’s borrowing card to receive a card from that library. PLAC cards may be purchased at the circulation desk at any public library. The cost of a PLAC card in 2022 is $65 per person per year and cards may be used for 12 months from the date of purchase. Before purchasing a card, a borrower must first have a current borrower card (or paid non-resident card, if they live in an area with no library service) from a public library district. For more information on the PLAC program, visit this page.

Interlibrary Loan

If you are interested in accessing the books or media on shelves at other Indiana public libraries, but are unable to visit in person, enquire with your local public library about interlibrary loan or other borrowing options. There is a statewide network of delivery vehicles that transport library materials around the state daily.

Evergreen Indiana

Is your public library an Evergreen Indiana library? Then you already have access to most of the materials at other libraries at over 100 other Evergreen libraries. Simply request materials from other Evergreen libraries to be shipped to your home library, or show your green Evergreen Indiana card to borrow in person from other participating libraries.

Please note that while libraries are happy to share with other libraries, whenever possible, materials should always be returned directly to the lending library, or the library from which that item was borrowed in the case of interlibrary loans or Evergreen loans.

We are happy to let the secret out about these ways to maximize your borrowing power. Happy reading!

This blog post was written by Jen Clifton, Library Development Office director. She can be reached via email.