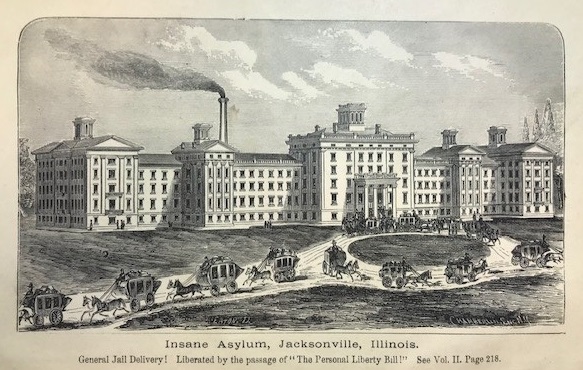

On the morning of June 18, 1860 an Illinois housewife named Elizabeth Packard was forcibly removed from the home she shared with her husband Theophilus Packard, a Calvinist minister, and their six children. The reason for her expulsion? Her husband was having her committed to the Illinois State Hospital in Jacksonville, Illinois. Women had virtually no legal status in mid-19th century America and in the state of Illinois, a husband could have his wife committed to an insane asylum without showing any proof that said wife was, in fact, insane. Theophilus and his wife often quarreled over religious doctrines, with Elizabeth insisting that she had a right to her own beliefs and biblical interpretations and this, it seems, was her husband’s primary justification for having her institutionalized and removed from the lives of her children.

Elizabeth spent three years in the asylum with very few means to advocate for herself and her sanity. While incarcerated, she met many other women in similar situations, women who had become inconvenient or were socially noncompliant and therefore needed to be locked away by husbands or other family members. Some women did suffer from various mental health issues and Elizabeth frequently witnessed their cruel treatment at the hands of hospital staff. She diligently wrote down her observations and hid her journals to keep them from being confiscated.

In 1863, she was released from the asylum to the care of her husband who immediately sought to have her permanently recommitted to yet another institution, this time in Massachusetts. In a desperate bid for freedom and with the help of friends, Elizabeth was finally able to obtain legal assistance. After a multi-day trial, she was deemed legally sane in the state of Illinois. Unfortunately, before the verdict affirming her sanity was rendered Theophilus fled to another state with her children. Despite being found officially sane, as a woman she still had little legal recourse to regain custody of her children.

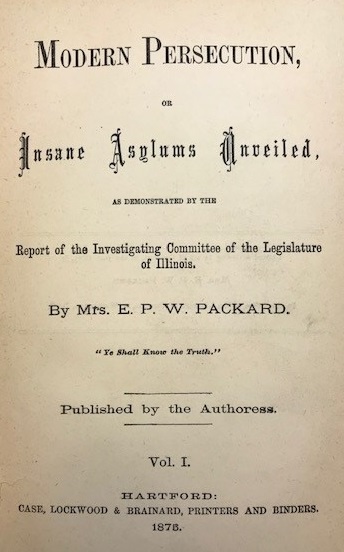

Bereft at the loss of her family, Elizabeth began to publicly advocate for changes to the treatment of those deemed insane with a particular emphasis on the rights of female patients. She published various books drawing from her personal experiences, shedding light on rampant institutional abuse and calling for major reforms. Of particular concern to her was the right of patients to freely correspond with those outside the asylum without said correspondence being censored – or discarded – by asylum officials. For those improperly imprisoned such as herself, communicating freely with someone on the outside meant that inmates could access the meager legal resources and other practical support available to them. It meant that women could no longer be locked up, never to be heard from again.

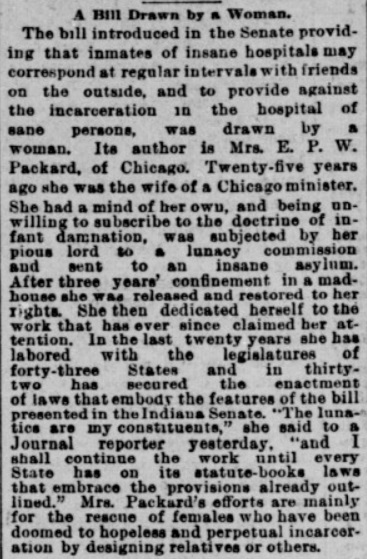

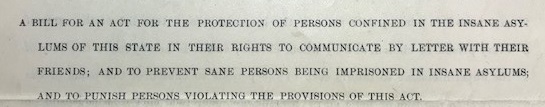

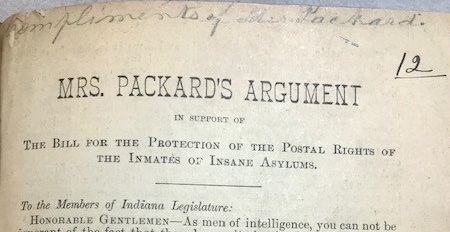

Elizabeth also travelled the country lobbying individual state legislatures to change their laws. In 1891, she set her sights on Indiana and promoted a “Bill for the protection of the postal rights of the inmates of insane asylums.” She implored members of the Indiana legislature that such a law was needed as “a potent remedy for the evils of false imprisonment, unreasonably long detention and abuse of patients.” Senator W.C. Thompson of Marion County officially read and introduced the bill as Senate Bill 55 on Jan. 14, 1891 and it was referred to the Committee on Benevolent Institutions for further consideration.

Caption to a pamphlet addressed to the Indiana legislature dated Feb. 3, 1891 (ISLI 362.2 no. 61). Note “Compliments of Mrs. Packard” written in pencil at the top of the page.

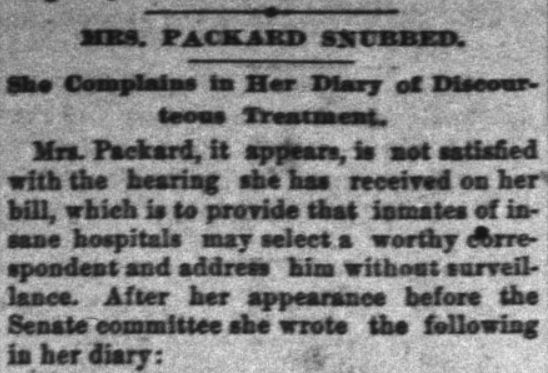

According to a subsequent news story titled “Mrs. Packard snubbed,” it appears that Elizabeth herself attended the Committee hearing on her bill but was completely ignored by the men in attendance:

“I have this morning met by appointment the Senate Committee on Benevolent Institutions, in room 113 of the Capitol at 7 o’clock, and was there completely gagged, not allowed to speak one word.”

She concluded her description of the event with a strong condemnation of the behavior of Indiana’s male law-makers:

“To the manliness and honor of the American legislators, I am proud to say that thus is the first uncourteous treatment I have ever received from any legislative committee in these United States. In appealing to forty-three different legislatures I have invariably been allowed a manly, patient hearing before they decide how they should report my bill.”

In addition to silencing Mrs. Packard, the committee caused further offense by severely altering the language of the original bill and stipulating that the only person an inmate could correspond with uncensored would be the Secretary of the Board of State Charities. Moreover, the committee further recommended to remove the phrase “to prevent sane persons being imprisoned in insane asylums” from the language of the bill. The resulting document was a failure as it continued to leave all the power with the very institutions responsible for committing the abuses Elizabeth sought to remedy.

Ultimately, Senate Bill 55 never progressed passed its second reading. Despite this failure, Elizabeth Packard’s entreaties did lay the groundwork for Hoosier legislators to begin considering similar reforms. Eventually, the General Assembly would pass progressive legislation, such as an act in 1895, which required those accused of insanity to stand for an official inquest with proper legal representation.

Elizabeth Packard was reunited with her children – but remained estranged from her husband – and financially supported them with her earnings from writing and public speaking. She died July 25, 1897.

An excellent biography of Elizabeth by Kate Moore titled “The woman they could not silence” was released in 2021 and is available to circulate from the Indiana State Library.

This blog post was written by Jocelyn Lewis, Catalog Division supervisor, Indiana State Library. For more information, contact the Indiana State Library at 317-232-3678 or “Ask-A-Librarian.”

Sources

Indiana. “Journal of the Indiana State Senate, 57th session,” Jan. 8, 1891. (ISLI 328 I385Ljs 1891)

Indiana. “Laws of the State of Indiana, 57th regular session,” Jan. 8, 1891. (ISLI 345.1 I385 1891)

Indiana. “Laws of the State of Indiana, 59th regular session,” Jan. 10, 1895. (ISLI 345.1 I385 1895)

More, Kate. “The woman they could not silence: One woman, her incredible fight for freedom, and the men who tried to make her disappear.” Naperville, Illinois: Sourcebooks, 2021. (ISLM HN80.P23 M66 2021)

Packard, Elizabeth Parsons Ware. “Modern Persecution, or Insane Asylums Unveiled, as Demonstrated by the Report of the Investigating Committee of the Legislature of Illinois.” Hartford: Case, Lockwood & Brainard, 1875. (ISLM RC439 .P16 1875)

Packard, Elizabeth Parsons Ware. “Mrs. Packard’s argument in support of the bill for the protection of the postal rights of the inmates of insane asylums.” Indianapolis, 1891. (ISLI 329 I385 v.2, no. 12)

Packard, Elizabeth Parsons Ware. “A bill for the protection of persons confined in the insane asylums of this state in their rights to communicate by letter with their friends; and to prevent sane persons being imprisoned in insane asylums; and to punish persons violating the provisions of this act.” Indianapolis, 1891. (ISLO 362.2 no. 61)