During this time of social distancing, some of us are likely missing our favorite watering holes and beloved bartenders. What better time to tell one of their stories? Bartender extraordinaire, William “Sonny” Wharton was born around 1905 in Nashville, Tennessee. Our story finds him much later on in Evansville, Indiana, where Wharton was mentioned in the Evansville Argus when that newspaper first began its run in 1938. The Evansville Argus was a weekly African American newspaper published in Evansville from 1938 to 1945 and included local, national and international news. By the end of 1938, Wharton began an informal column on liquor and mixing drinks. At the time, he was likely working at the Lincoln Tap Room, located at 322 Lincoln Avenue, per articles from early 1939. It’s clear that “Sonny” had much to say and a wealth of knowledge on the fine art of imbibing. His column began with insight into the importance of garnishes, the premiere liquors to choose for your cocktails and the etiquette of glassware amongst other topics. As time went on, he also began sharing more recipes.

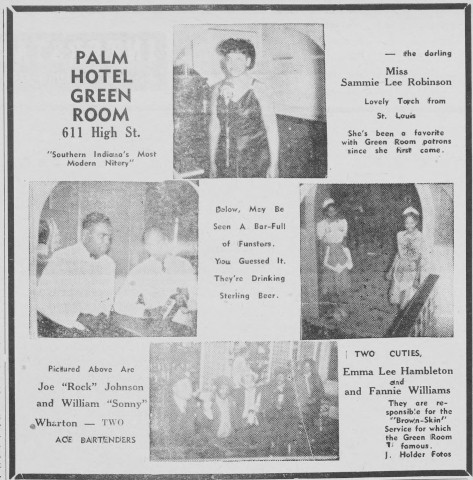

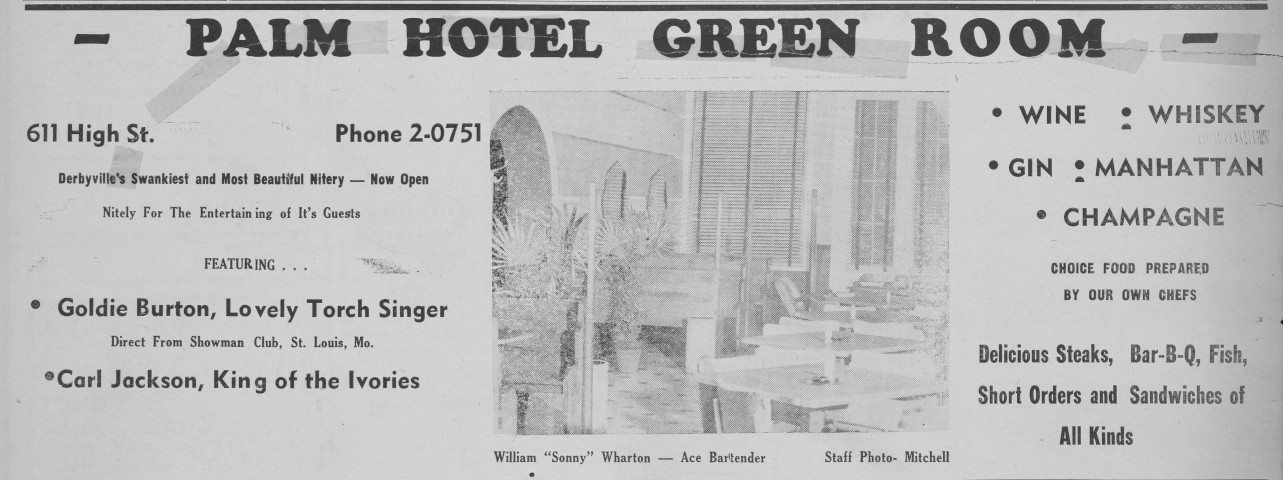

Wharton was best known for working at the Green Room at the Palm Hotel, which was located at 611 High Street. He was a mainstay in Evansville’s black community and his expertise behind the bar at the Palm Hotel was advertised heavily. He was “night time head bartender” in the Green Room for most of the early 1940s. By early 1939, his Argus column had developed into “Tid-bits from Sonny” and featured regular cocktail recipes. While many spirits were in limited supply due to wartime restrictions, rum was readily available during the 1940s due to trade with Latin America and the Caribbean. Rum’s availability and popularity is reflected in Sonny’s columns and recipes.

Wharton was best known for working at the Green Room at the Palm Hotel, which was located at 611 High Street. He was a mainstay in Evansville’s black community and his expertise behind the bar at the Palm Hotel was advertised heavily. He was “night time head bartender” in the Green Room for most of the early 1940s. By early 1939, his Argus column had developed into “Tid-bits from Sonny” and featured regular cocktail recipes. While many spirits were in limited supply due to wartime restrictions, rum was readily available during the 1940s due to trade with Latin America and the Caribbean. Rum’s availability and popularity is reflected in Sonny’s columns and recipes.

In his personal life, Wharton had a daughter with Leola Marshall of Indianapolis. Both Leola and their daughter, Juanita Oates – later Johnson – worked for the Madam C.J. Walker Company in Indianapolis. Johnson later became the manager of the Madam Walker Theatre Center. Additionally, “Sonny” was married to Naomi Wharton, but they divorced in 1941.

In his personal life, Wharton had a daughter with Leola Marshall of Indianapolis. Both Leola and their daughter, Juanita Oates – later Johnson – worked for the Madam C.J. Walker Company in Indianapolis. Johnson later became the manager of the Madam Walker Theatre Center. Additionally, “Sonny” was married to Naomi Wharton, but they divorced in 1941.

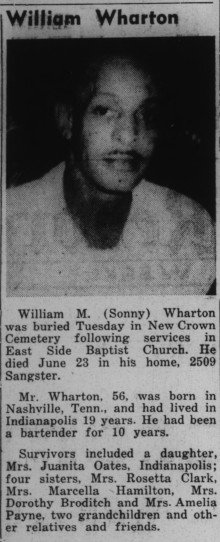

The lifetime of the Palm Hotel could not be determined by the author at this time, but it was advertised with “Sonny” as its bartender into 1943. Wharton’s obituary notes that he had lived in Indianapolis for 19 years upon his death in 1961, so it’s clear that he left Evansville around this time, although the reason is not known.

The lifetime of the Palm Hotel could not be determined by the author at this time, but it was advertised with “Sonny” as its bartender into 1943. Wharton’s obituary notes that he had lived in Indianapolis for 19 years upon his death in 1961, so it’s clear that he left Evansville around this time, although the reason is not known.

Thankfully, the legacy of good times and good drinks continues and Wharton left behind his column for us. I decided it was only right that one evening after work I re-create, to the best of my ability, one of the cocktails he noted as a favorite. I chose the commodore, which was referenced twice in his column. A brief internet search on this drink notes that it also appeared in “The Old Waldorf-Astoria Bar Book” from 1935. While I had most of the ingredients on hand, mixing this drink did involve a commitment to making fresh raspberry syrup. Not as difficult as you’d think, actually! I used aquafaba in lieu of egg white and eliminated the additional half teaspoon of sugar surmising that it would push the drink over the edge in terms of sweetness for my taste. Served in a martini glass, the commodore is sweet, frothy and certainly boozy. It’s sure to brighten your day and maybe even make you forget your troubles. If fruit and rum aren’t your game, you can find more “Tidbits from Sonny” in the Evansville Argus via Hoosier State Chronicles. Cheers!

Thankfully, the legacy of good times and good drinks continues and Wharton left behind his column for us. I decided it was only right that one evening after work I re-create, to the best of my ability, one of the cocktails he noted as a favorite. I chose the commodore, which was referenced twice in his column. A brief internet search on this drink notes that it also appeared in “The Old Waldorf-Astoria Bar Book” from 1935. While I had most of the ingredients on hand, mixing this drink did involve a commitment to making fresh raspberry syrup. Not as difficult as you’d think, actually! I used aquafaba in lieu of egg white and eliminated the additional half teaspoon of sugar surmising that it would push the drink over the edge in terms of sweetness for my taste. Served in a martini glass, the commodore is sweet, frothy and certainly boozy. It’s sure to brighten your day and maybe even make you forget your troubles. If fruit and rum aren’t your game, you can find more “Tidbits from Sonny” in the Evansville Argus via Hoosier State Chronicles. Cheers!

This blog post was written by Lauren Patton, Rare Books and Manuscripts librarian, Indiana State Library. For more information, contact the Indiana State Library at 317-232-3678 or “Ask-A-Librarian.”

This blog post was written by Lauren Patton, Rare Books and Manuscripts librarian, Indiana State Library. For more information, contact the Indiana State Library at 317-232-3678 or “Ask-A-Librarian.”