Kristin Lee, Rare Books and Manuscripts digitization and metadata assistant, has been digitizing and creating metadata for the Will H. Hays Collection since October 2018. This project is funded by a National Historical Publications and Records Commission, Access to Historical Records, Archival Projects grant.

Tell us a little bit about yourself and why you decided to work on this project.

My name is Kristin and I’m originally from Turlock, California, but I’ve been living here with my cat Josephine for about four years. I moved to Indianapolis to pursue a master’s degree in Public History at IUPUI. While in grad school, I had the opportunity to work with the Rare Books and Manuscript Division at the Indiana State Library as an intern and I was excited to work at ISL on another project. I was also interested in this project because the Will Hays Collection is one of the Library’s most-viewed collections and I knew that digitization would help broaden its use and accessibility for researchers outside our immediate community.

What have you learned about Hays or the film industry that you didn’t know?

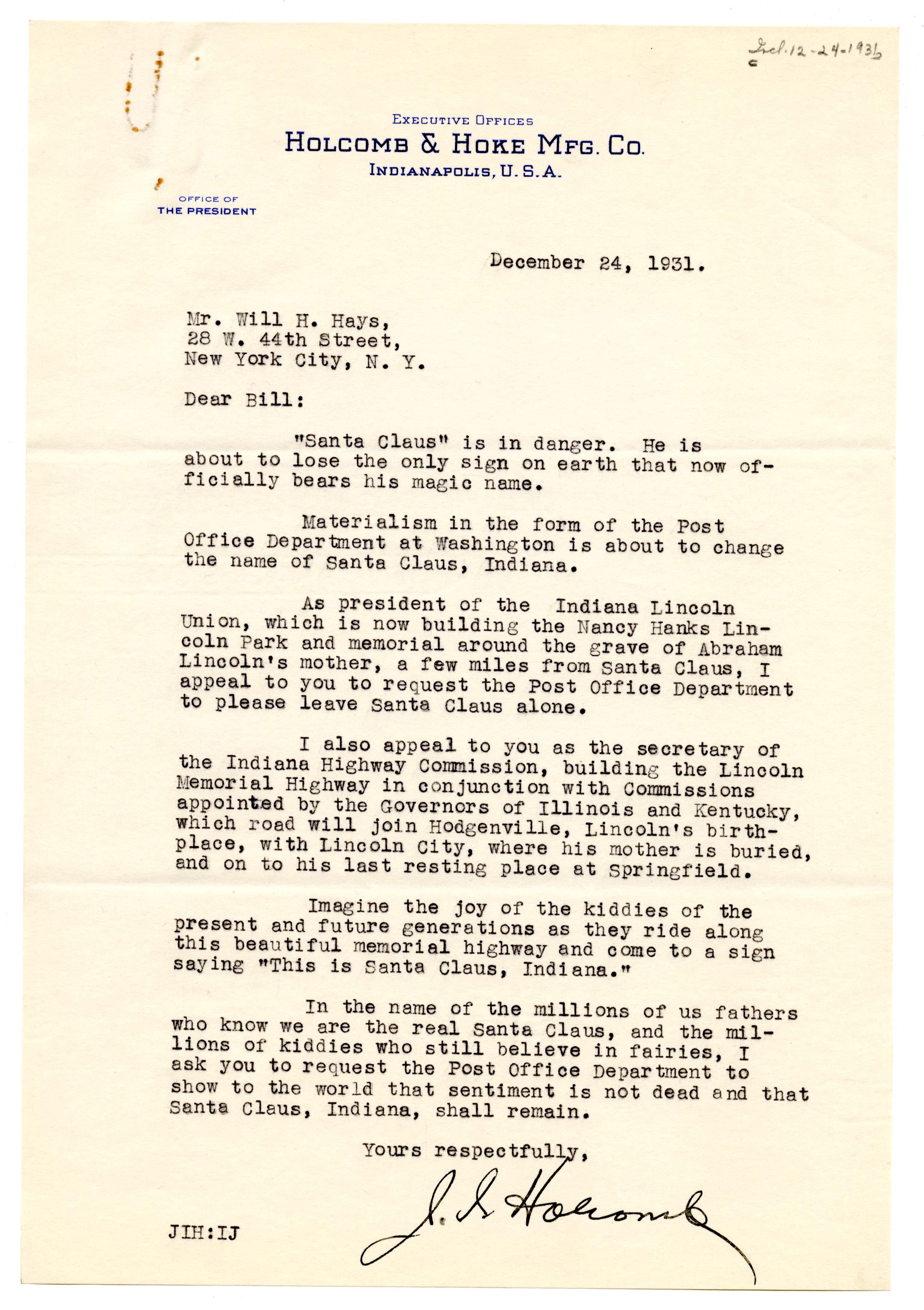

One of the things that surprised me was how negatively people reacted to Hays’s move to the film industry and the film industry as a whole. Particularly during his last weeks as Postmaster General. Hays received so many letters from people who begged him to stay at his post and who saw movies as corrupt and immoral or just a passing fad. A few years later when “talkies” started getting produced, people again reacted with suspicion. I remember one critic writing that talking pictures would be the downfall of the film industry because movie actors, while excellent pantomimes, had terrible voices! It was really interesting to learn that people had such a negative outlook for the film industry when it’s a form of entertainment that is so normal to me.

What’s your favorite item you’ve discovered within the collection?

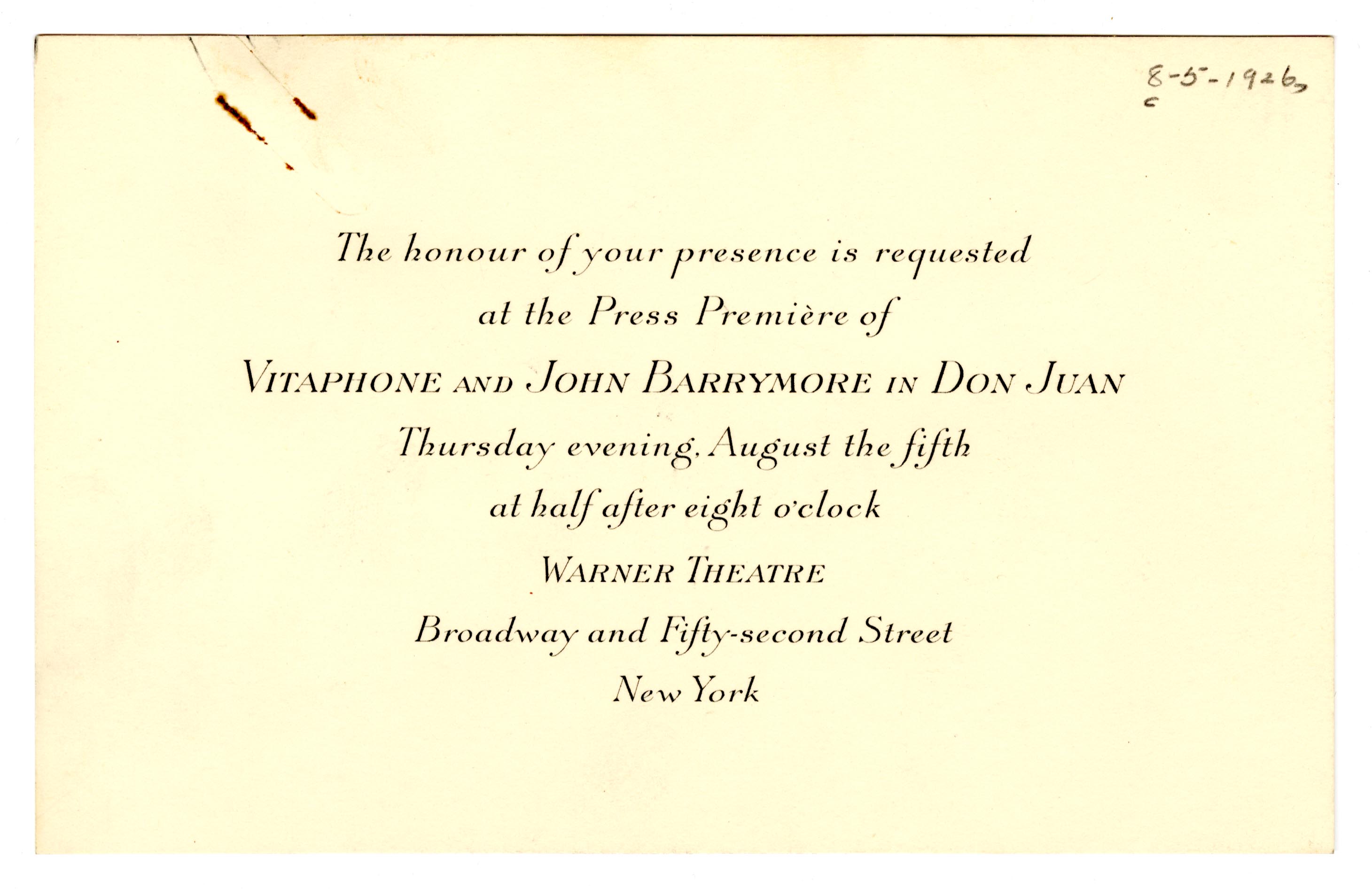

My favorite item from the collection is an invitation to the premiere of the film “Don Juan” on Aug. 5, 1926. “Don Juan” was the first feature film to use the Vitaphone sound system to create a moving picture with synchronized sound. The film included a musical soundtrack and sound effects, but no spoken dialogue; the first actual “talkie,” “The Jazz Singer,” would premiere in 1927. “Don Juan” also included several shorts before the film that showed off Vitaphone sound. One of these shorts was of Hays introducing the Vitaphone and talking about the future of sound in films; a copy of this short is available to watch on YouTube – it’s fun being able to hear Will Hays and watch him speak. He liked using a lot of hand gestures!

How has working on this project shaped your views of providing access to and preserving collections?

How has working on this project shaped your views of providing access to and preserving collections?

Working on the Will Hays project has only reinforced my views on the importance of making digital versions of historical sources. Digitization increases the availability of collections to researchers who are not able to visit the Indiana State Library in person. As more people have access to this collection, we will continue to learn new information about Will Hays and the early film industry. Also, because some of the correspondence has become brittle and crumbly with age, digitization will help us preserve these items for researchers for years to come. Lastly, I have also come to really appreciate the work of all the people who digitized the records that I used as a student in college and grad school for my research… I know how much work goes into it now!

This blog post was written by Bethany Fiechter, Rare Books and Manuscripts supervisor, and Kristin Lee, Rare Books and Manuscripts digitization and metadata assistant, Indiana State Library. For more information, contact the Indiana State Library at 317-232-3678 or “Ask-A-Librarian.”