Lydia Lutz, Rare Books and Manuscripts digitization and metadata assistant, has been digitizing and creating metadata for the Will H. Hays Collection since October of 2018. This project is funded by a National Historical Publications and Records Commission, Access to Historical Records: Archival Projects grant.

Tell us a little bit about yourself and why you decided to work on this project.

I earned my Master of Library Science from Indiana University in 2017. Before realizing my passion for digitization and preservation of various artifacts, I always enjoyed watching shows on the History Channel and National Geographic about ancient papers and pieces being restored and shared with the public. Prior to coming here, I prepped materials for the Media Digitization and Preservation Initiative and digitized a collection for the Glenn Black Laboratory of Archaeology at Indiana University. I have worked with analog audio-visual and paper-based media. I was mostly drawn to this project because of the Hays Code. It’s a term I’d heard in passing and its definition was somewhat familiar to me. I wanted to learn more about the man behind Hollywood’s moral code and about the code’s influence on the industry. Having just come from the world of antique audio formats and watching their transformation into their modern form, I was curious about the world of film. I also knew that by digitizing the Hays Collection I would be a part of someone’s introduction or further exploration into Hays and his era. It is nice to know that your work makes difference and can be useful to others.

What have you learned about Hays or the film industry that you didn’t know?

I didn’t realize how complex the shift from silent films to films with sound – even just background music – was. I saw a documentary a few years ago that addressed the shift from actors’ and actresses’ viewpoints. From their positions, some didn’t like their voices or their voices didn’t fit the characters they portrayed. Other times their production companies would have them in a contract forbidding them from using their voices in films. The documentary did not discuss society’s viewpoint on the shift though. Judging by the correspondences and the news articles in this collection, one of the most problematic consequences of this shift was moviegoers and companies fearing the watching experience would be ruined by sound and that audio should be left to the theater. I can’t fathom living in an era where sound films would be considered a poor distraction. Seeing the transition play out through the collection was certainly fascinating.

As for Hays, I have learned that he could be very sassy in his letters to friends, which is lovely because it makes him seem less like a myth and more like a human being.

What’s your favorite item you’ve discovered within the collection?

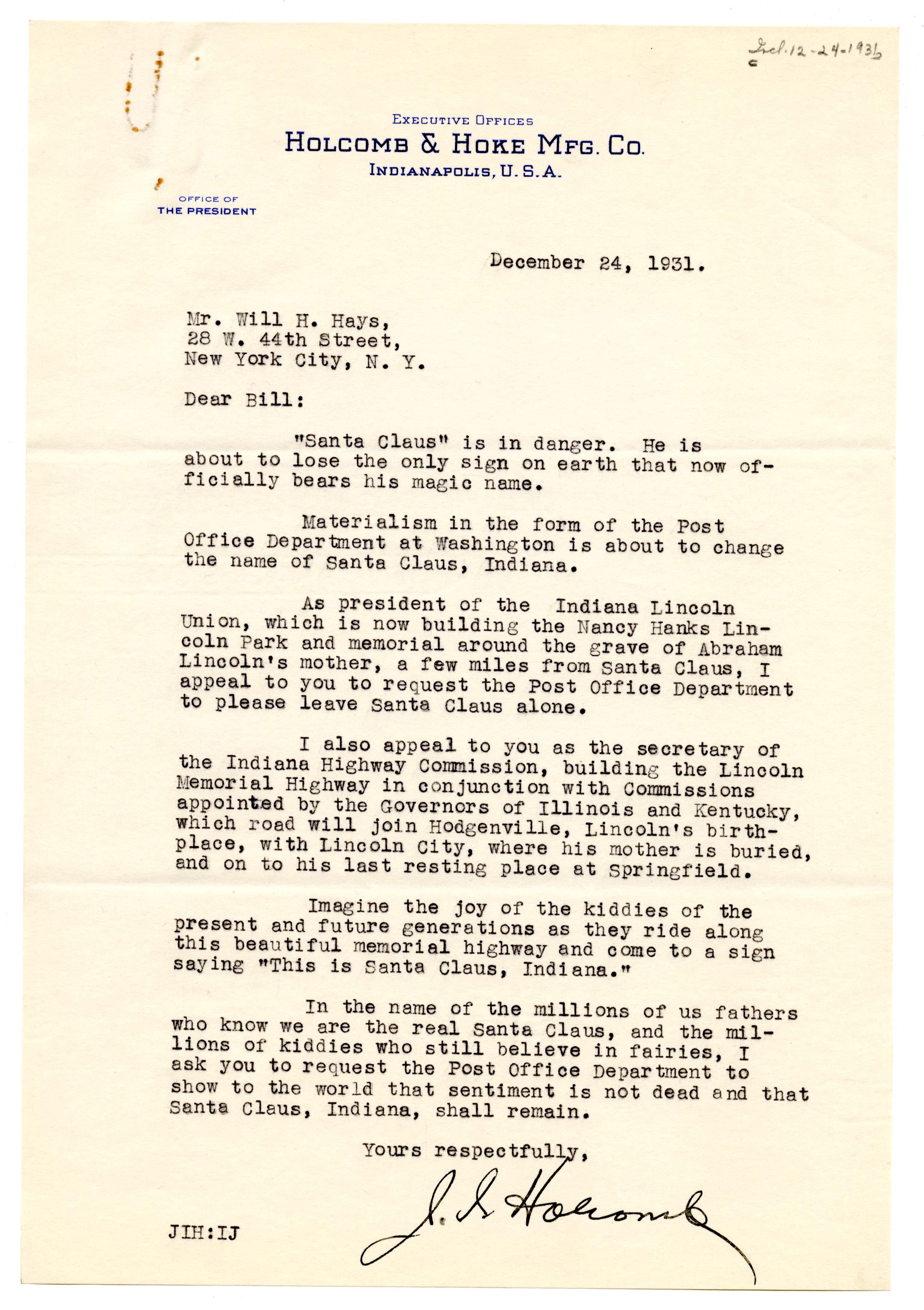

My favorite item was a letter written on Christmas Eve 1931 to Mr. Hays regarding a highway that was going to essentially remove Santa Claus, Ind. from the map. The author was pleading that Santa Claus remain a town name because future generations of children would miss out on the wonder of passing through Santa Claus’s home. It was an eye-opening piece because I grew up going to Holiday World to see Santa and my parents went to Santa Claus Land for the same reason. Without the town these parks may never have been conceived. Perhaps this letter played a role in maintaining the magic of Santa Claus for past, present and future children and dare I say, adults.

My favorite film-related item would be production information about Lon Chaney’s silent film, “The Phantom of the Opera” simply because I love that movie.

How has working on this project shaped your views of providing access to and preserving collections?

My views on accessibility and preservation only continue to be strengthened through projects such as this. It is important for the public to have the opportunity to see how society has been shaped in order to boost their understanding of how we got to where we are. It seems cliché, but knowing the timeline of our history can change perspectives on our present. It is also fun to learn for the sake of learning. On a more serious note, though, without preservation historical cultural practices could go unnoticed by future generations and movements, such as moral codes in cinema, could be erased from living memory.

This project has also made me realize how much work needs to be done with text-to-speech software, however. Currently, the technology has the accuracy of public TV subtitles: sometimes whole sentences are omitted and words are often unrecognizable. The technology is great and certainly useful but it has a long way to go. I hope in the near future more intelligent technology can be created in order to share even more of this and other collections.

This blog post was written by Bethany Fiechter, Rare Books and Manuscripts supervisor, and Lydia Lutz, Rare Books and Manuscripts digitization and metadata assistant, Indiana State Library. For more information, contact the Indiana State Library at 317-232-3678 or “Ask-A-Librarian.”