The Indiana Union of Literary Clubs was started after the Indianapolis Woman’s Club was established at the Indianapolis Propylaeum. The Propylaeum, founded in 1888, was the central meeting place for many different women’s clubs in Indianapolis. At that time, there were already several different women’s literary clubs in Indianapolis alone. Although a rare men’s club is listed in the 1905 “Manual for the Indiana Union of Literary Clubs” (ISLO 374.2 NO. 7), the Union mostly consisted of women’s literary groups.

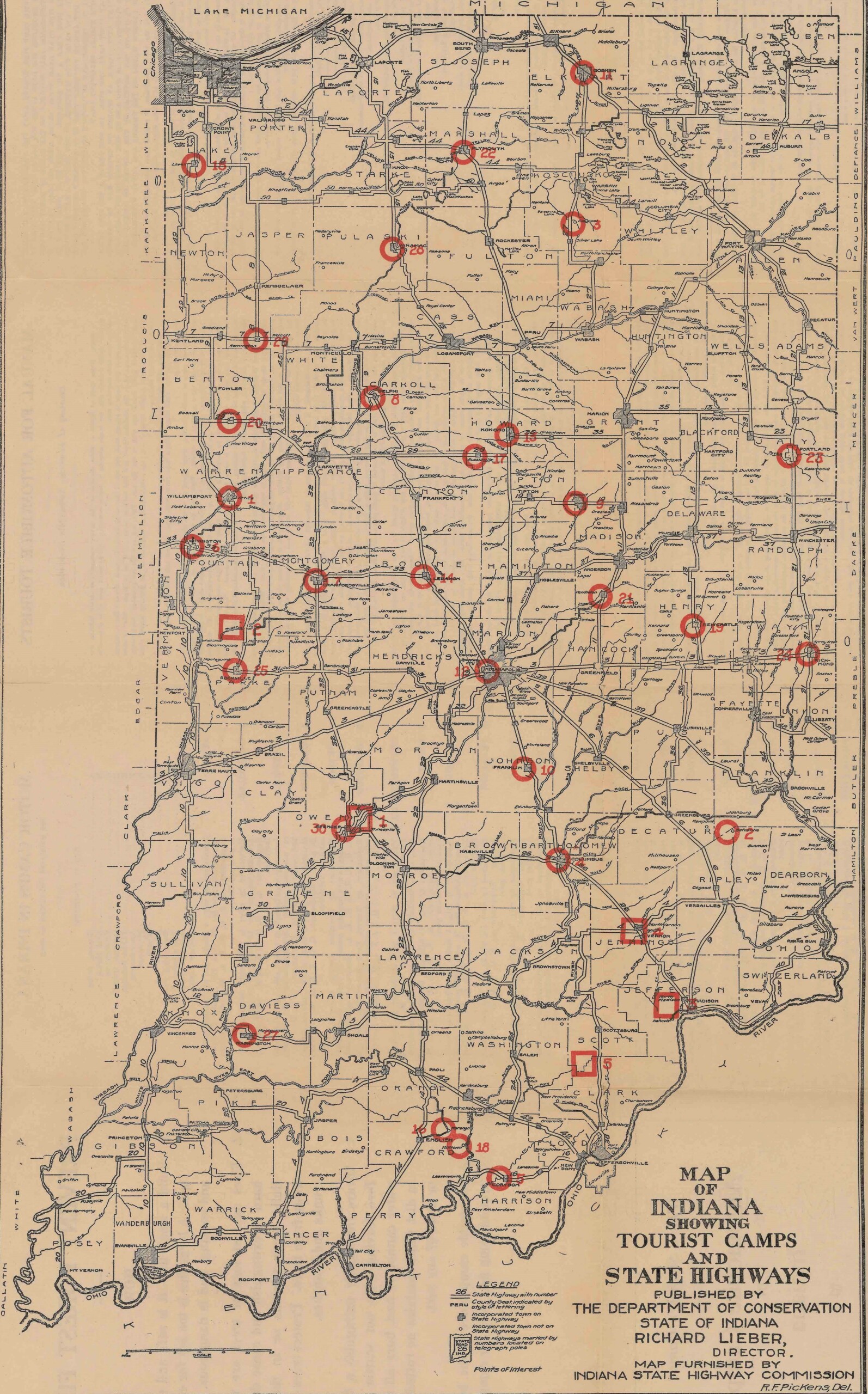

The late 19th and early 20th centuries were the height of popularity for literary clubs. By 1894, there were 175 organizations in the Union of Literary Clubs around the state of Indiana, according to “Literary Clubs of Indiana” (ISLI 810.6 M 153) by Martha Nicholson McKay. Of these, there were roughly five times as many women’s clubs than men’s clubs. Of the twenty men’s clubs, half were existing organized college literary societies (McKay, p 33).

The popularity of literary clubs among women seemed to point to a growing sense of intellectual curiosity. This could have been due to women seeking to improve so that “when the day of larger social and political freedoms dawns, they will be prepared for the new duties the wider field may disclose” (McKay, p.33). The boom in literary clubs also coincided with the suffragist movement in the United States.

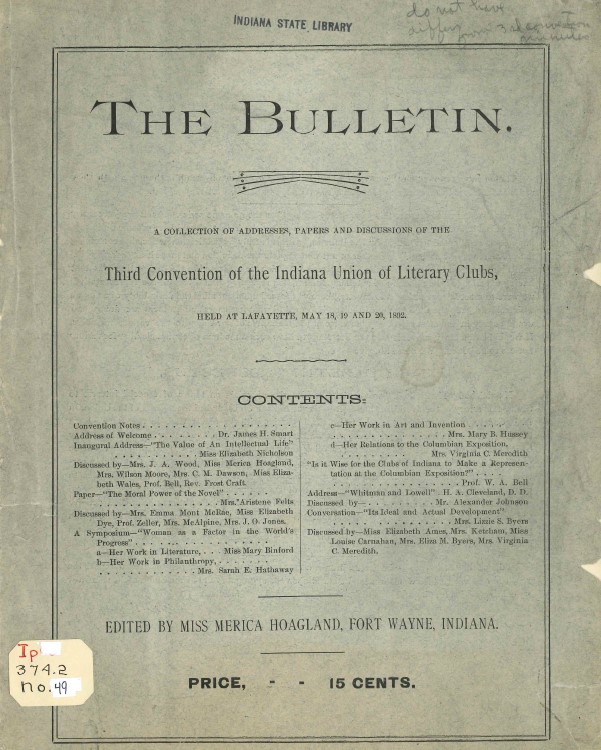

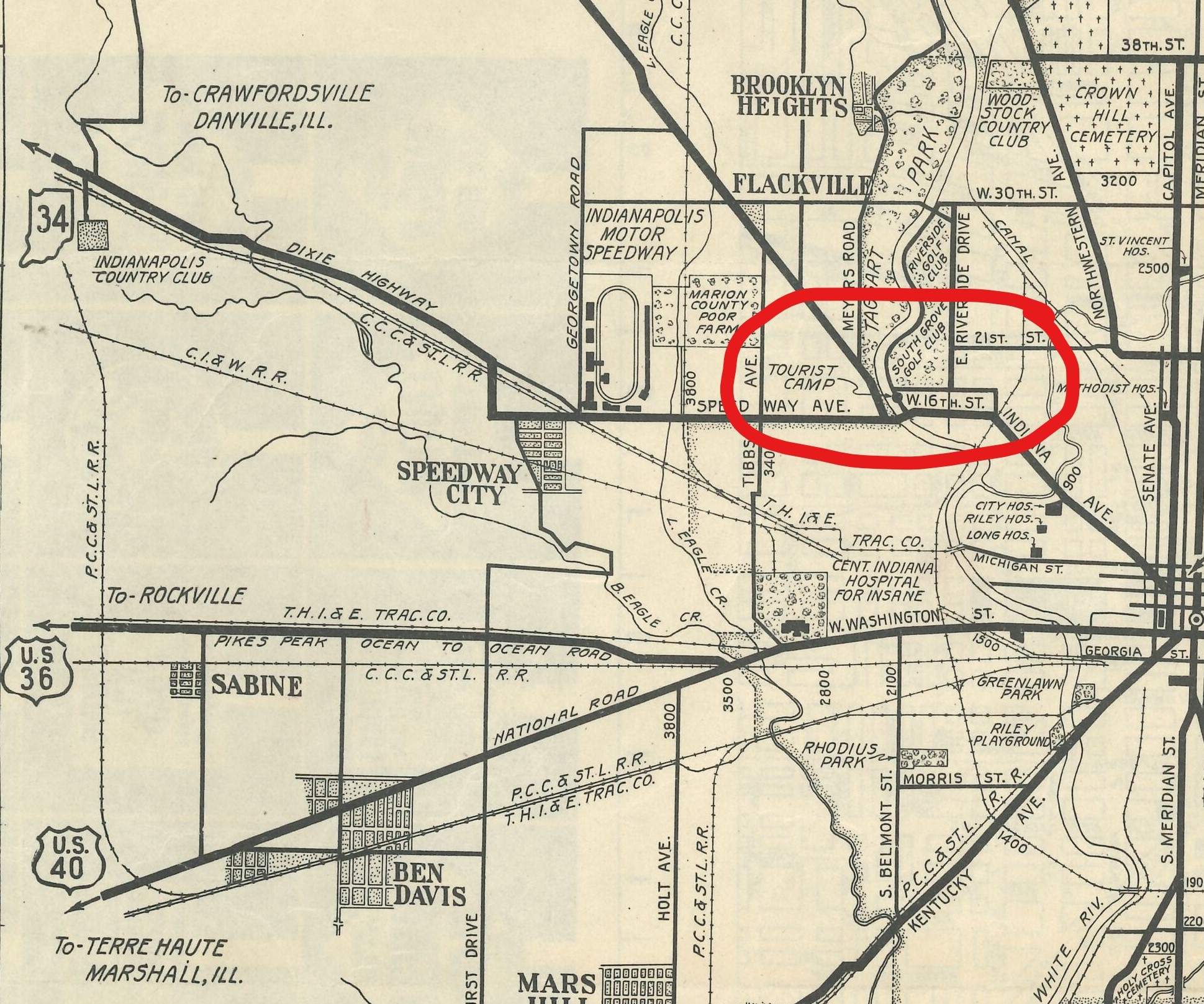

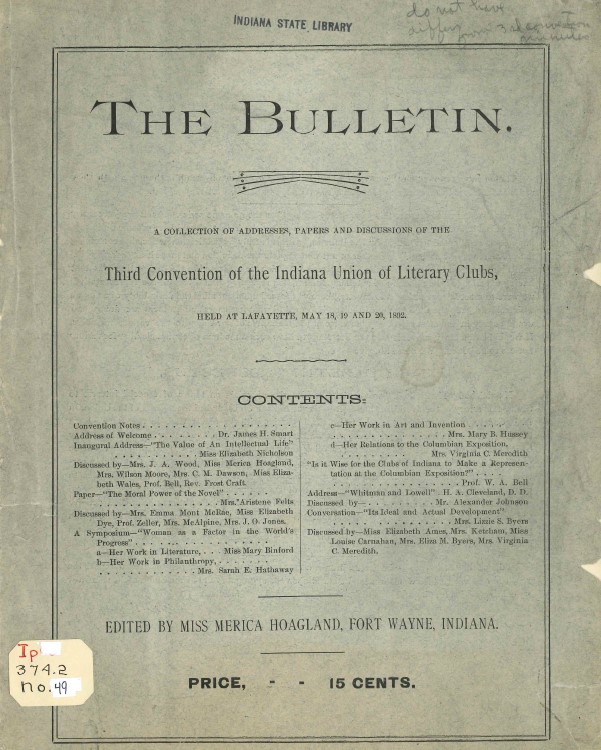

To organize the numerous literary clubs around the state in the early 1890s, the Indiana Union of Literary Clubs became the first state organization of clubs. In 1892, the third convention of the Indiana Union of Literary Clubs was held in Lafayette.

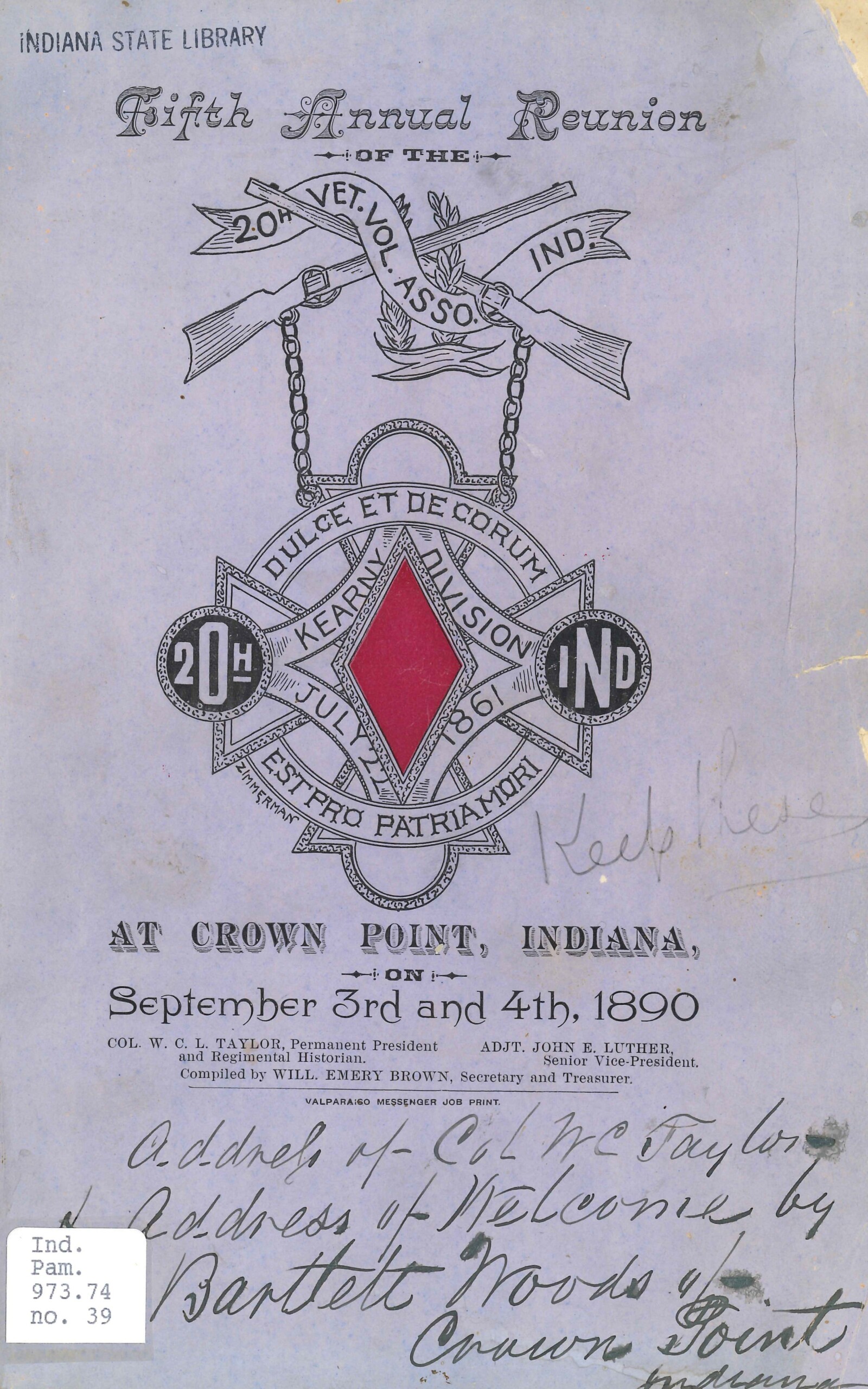

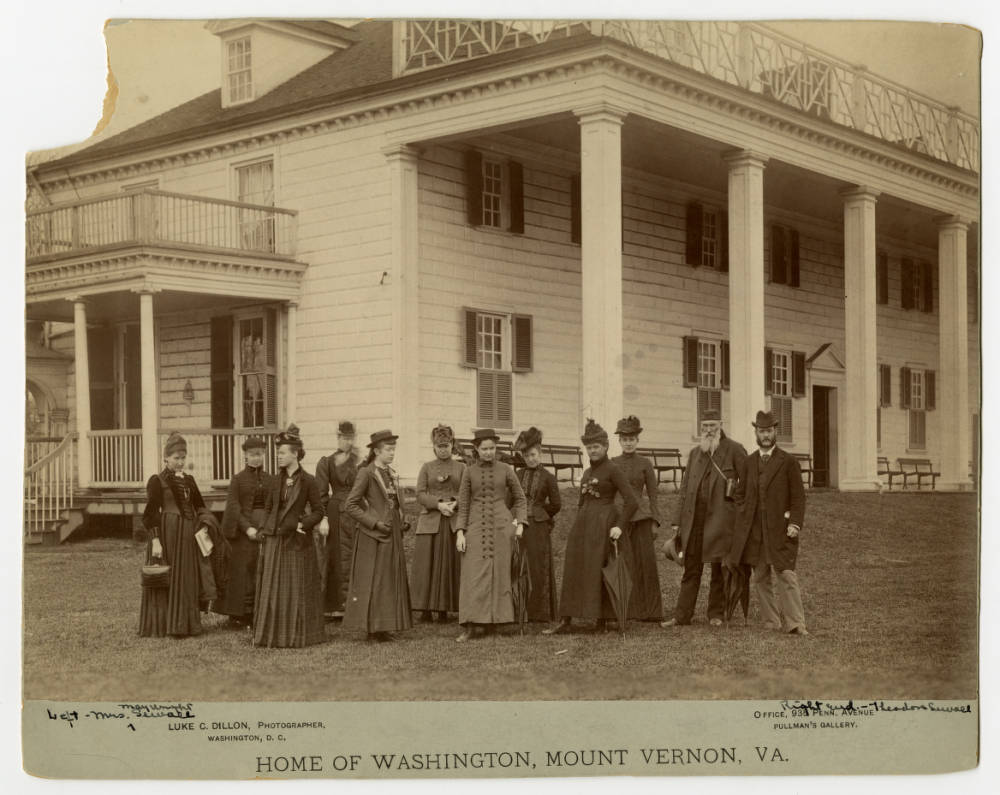

Here is the cover of the Bulletin from the 1892 convention of the Indiana Union of Literary Clubs from the Indiana Pamphlet Collection (Ip 374.2 no. 49.)

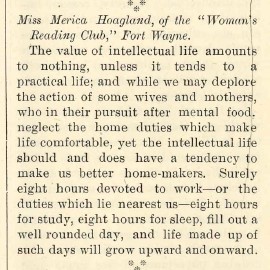

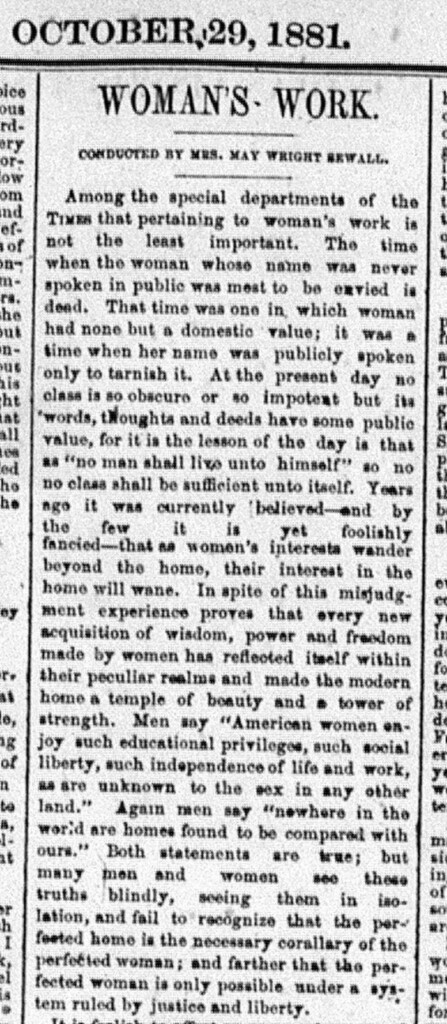

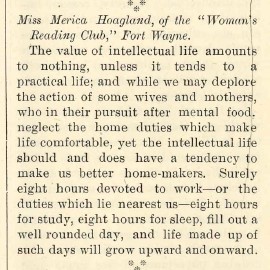

“The Bulletin,” (Ip 374.2 no. 49), a publication from the convention, provides a transcript of the inaugural address, “The Value of An Intellectual Life” by Miss Elizabeth Nicholson of the College Corner Club of Indianapolis. She indicated that there was a need for women to have intellectual pursuits in addition to their roles as homemakers. A common criticism of women’s clubs during that time period was that they took too much time and energy away from home and family responsibilities. Miss Mercia Hoagland, a representative of the Fort Wayne Women’s Reading Club responds to this type of criticism (Convention of the Indiana Union of Literary Clubs 1892 : Lafayette, p 3):

Other speeches and discussions at the convention included, “The Moral Power of the Novel” and “Woman as a Factor in the World’s Progress.” “The Bulletin” also recounted news from literary clubs around the state.

Other speeches and discussions at the convention included, “The Moral Power of the Novel” and “Woman as a Factor in the World’s Progress.” “The Bulletin” also recounted news from literary clubs around the state.

At the end of “The Bulletin,” there is a transcript of a discussion as to whether the Indiana Union of Literary Clubs should take an exhibit to the Columbian World Exposition in Chicago the following year. It was brought up that if they did take an exhibit, it would need to represent all the various literary clubs around the state.

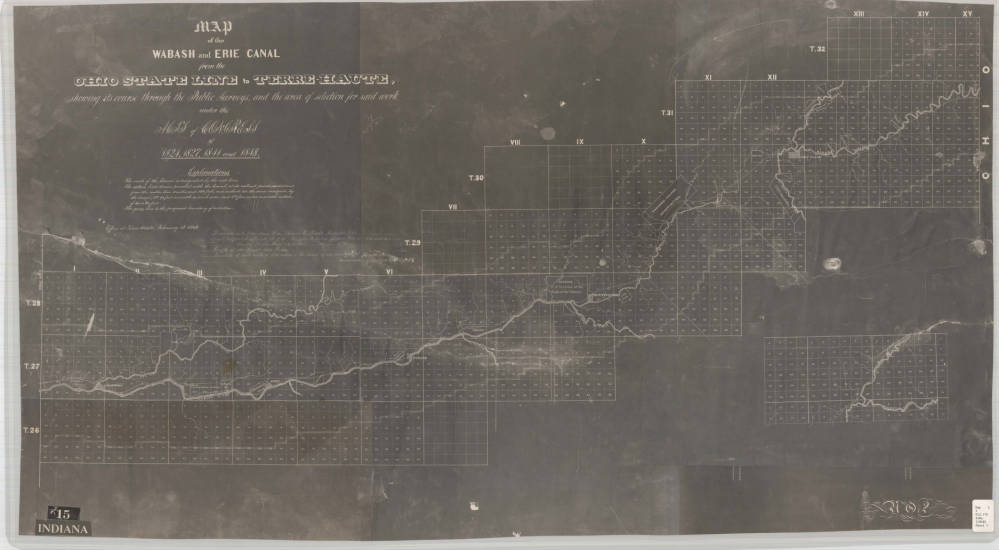

Ultimately, the Union did take an exhibit to the Columbian Exposition. The Indiana State Library has the item, “Exhibit of Work at Columbian Exposition,” in the Indiana oversize collection ([q] ISLI 374.2 I385E). These pages are examples of how each club contributed a program or leaflet that represented them.

This is the page representing the Ladies’ Literary Society from Brazil, Indiana. All participating clubs had a two-page entry in the book.

In 1906, the Indiana Federation of Women’s Clubs and the Indiana Union of Literary Clubs were consolidated and were renamed the Indiana State Federation of Clubs so that they could apply to become a chapter of the National Federation of Women’s Clubs.

Some of these literary clubs still exist today. For example, the Fortnightly Literary Club, established in 1885 is still active in Indianapolis. Hopefully, the love of knowledge, books and the pursuit of intellectual curiosity will never fade.

This blog post was written by Leigh Anne Johnson, Indiana Division Librarian, Indiana State Library. For more information, contact the Indiana State Library at (317) 232-3670 or “Ask-A-Librarian” Ask-A-Librarian.

Bibliography

“Convention of the Indiana Union of Literary Clubs 1892 : Lafayette, I.” (1892). The bulletin: a collection of addresses, papers and discussions of the third convention of the Indiana Union of Literary Clubs, held at Lafayette, May 18, 19 and 20, 1892. In M. E. Hoagland (Ed.). 1, p. 18. Lafayette: Indiana : Indiana Union of Literary Clubs, 1892. (Ip 374.2 no. 49)

“Indiana union of literary clubs – Reciprocity bureau.” (1905). Manual. unknown: unknown(ISLO 374.2 NO. 7).

McKay, M. N.-1. (1894). “Literary clubs of Indiana.” Indianapolis, Ind. United States: Indianapolis : Bowen-Merrill Co., 1894. (ISLI 810.6 M153).

The Indianapolis Fortnightly Literary Club. (May 11, 2022). Retrieved from https://fortnightly.org/

Indiana Union of Literary Clubs. Exhibit of work at Columbian exposition. [Place of publication not identified], [publisher not identified], [date of publication not identified] ([q] ISLI 374.2 I385E).