Known primarily as a significant driving force in the national movement to ban the sale of alcohol, which it saw as a corrosive force destroying families, the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union was a national organization involved in many other endeavors, all of which were rooted in a fiercely religious approach to social reform. In addition to raising concerns about the evils of alcohol consumption, the WCTU also advocated for female suffrage, prison reform, raised concerns about child labor, promoted regular church attendance and even took an interest in eugenics. As a group, they also encouraged rather strict guidelines on how women should comport themselves. Much of their work stressed themes such as morality and purity and focused on women’s issues like home economics. One manifestation of this endeavor were the industrial schools created by various WCTU chapters throughout the country.

The Indiana division of the WCTU was formed in 1874. Several years later in 1890, a prominent Hendricks County Quaker named Addison Hadley decided to donate a sizeable plot of farmland to the WCTU for the creation of a home for “neglected, abandoned and orphan girls.” Located slightly southwest of the city of Danville, the Hadley Industrial School for Girls opened in 1894. Its motto was “Our ideal: Right living. Our method: Training in industry. Our field: The state.”

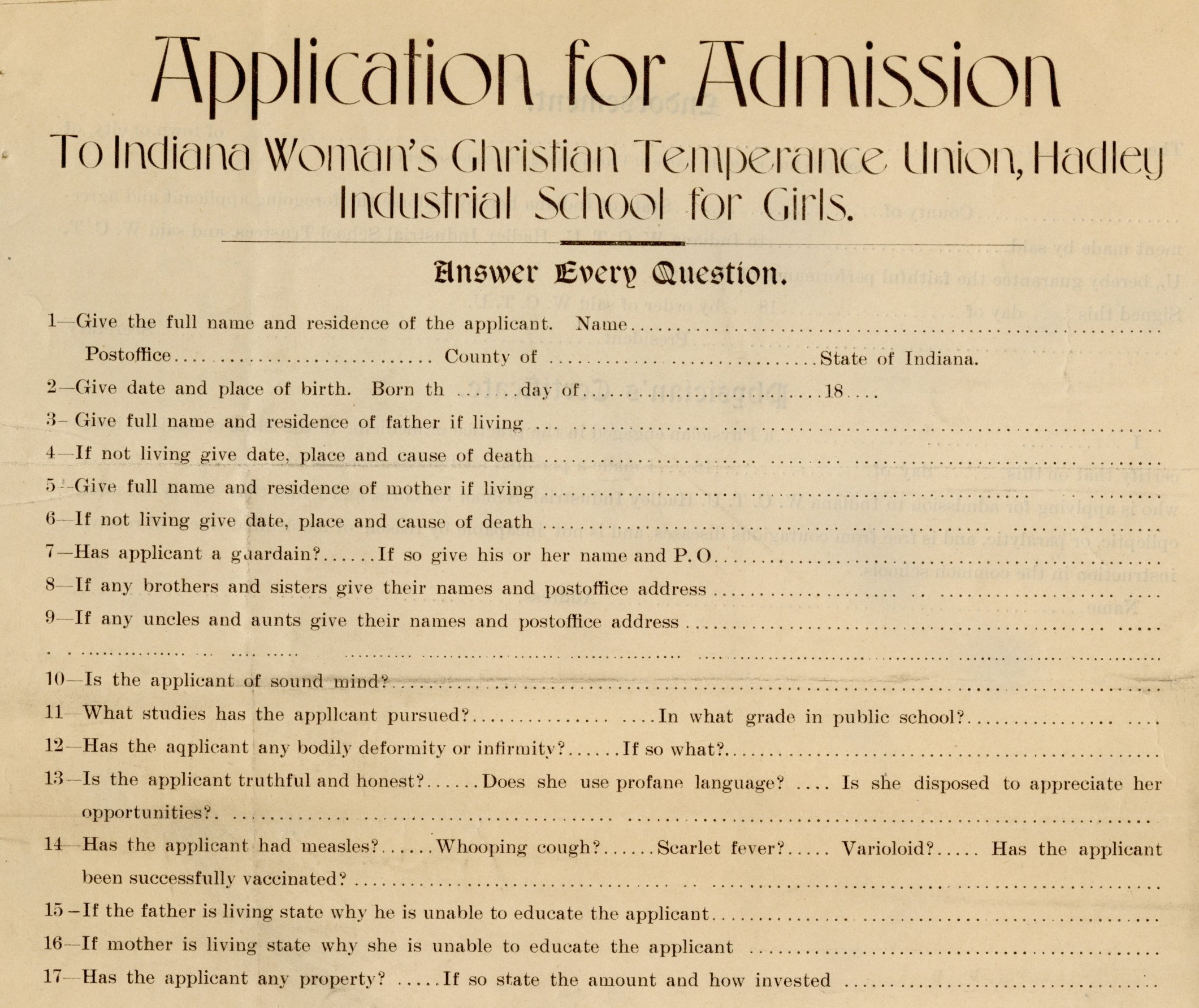

While the school was intended for young girls and teenagers who found themselves in dire conditions, there was still an expectation that it would only accept “worthy” girls who were not “incorrigible” and could be molded to the devout and industrious ideals espoused by the WCTU. This idea of worthiness is expressed in much of the informational pamphlets and annual reports produced about the school throughout its existence. Such sentiments were alluded to in the school’s application form with the following questions: “Is the applicant truthful and honest? Does she use profane language? Is she disposed to appreciate her opportunities?”

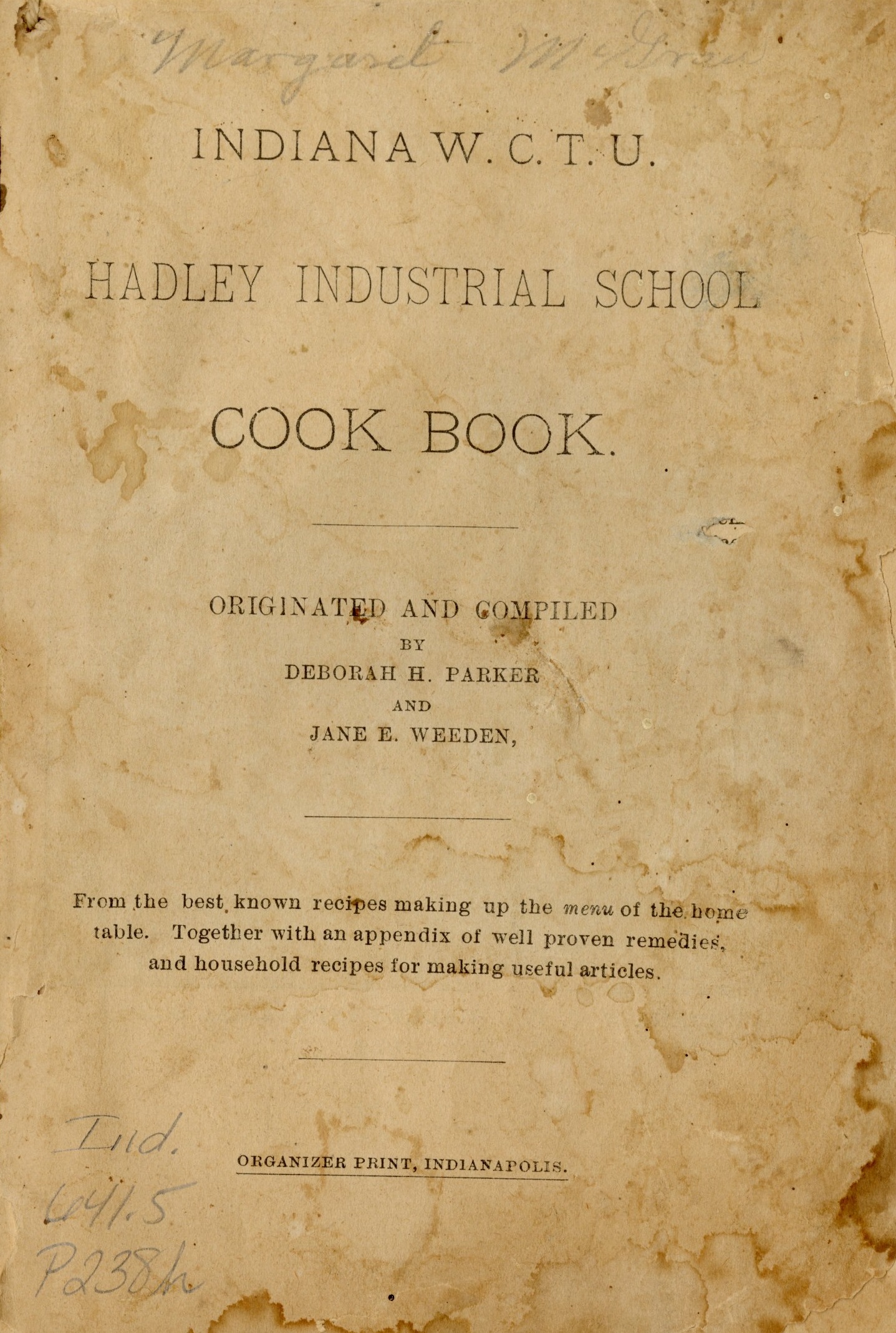

Once accepted to the Hadley School, girls were given an education involving a standard curriculum comparable to what would have been found in local public schools, as well as rigorous training in home economics. In addition to cleaning, cooking and sewing, the girls were expected to help run the farm. The farm produced butter, milk, eggs, jams and jellies, wheat and lumber. All money raised went back into the school. When not involved in educational or industrial pursuits, the girls regularly attended religious services and were expected to be involved in local temperance movement activities.

Despite the lofty but strict ideals on which it was based, the school struggled to be successful. A study of its annual reports show that funding was a perennial problem. Even though the school provided a fair amount of farm labor in the form of the girls themselves, running a farm was extremely arduous work in the late 19th century and required an actual farmer to oversee operations. The school had a difficult time retaining a competent farmer as they could not provide much commensurate financial compensation. The same held true for other staff at the school. There simply was not enough money to pay anyone. By the early 1900s, turnover was very high. According to the 1903 annual report, “the Managing Board has had much anxiety in regard to finding suitable officers to live at the school and keep the Home as it should be kept.” Crop failures, many of which stemmed from indifferent farming techniques, also compounded the school’s problems as did the inability to afford essential farm equipment. To further exacerbate issues, in 1904 the school’s teacher failed to pass a certification examination and the school lost what little public funding it received and was forced to send girls to the local public school for that part of their education.

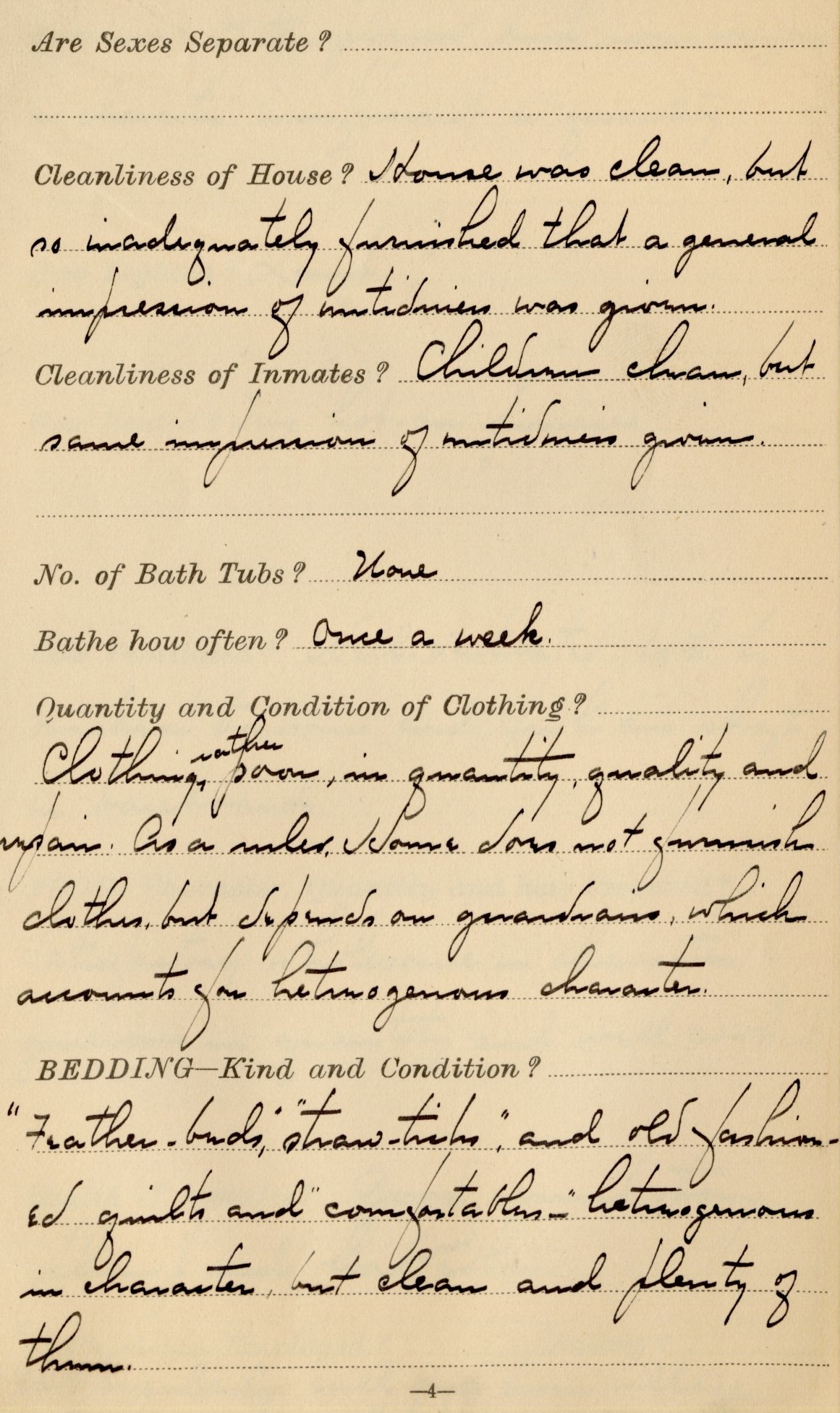

In 1902, a representative of the Board of State Charities conducted an inspection of the Hadley School. At the time of inspection, there were 35 girls living in the school. The building had no bathtub and the “home was clean but so inadequately furnished that a general impression of untidiness was given.” The girls’ clothing was considered “rather poor in quantity, quality and repair.” The school maintained a small library of “several hundred books” but the inspector felt that much of the literature was “too ‘red’ for the children.” However, not every observation was negative. The building was considered well-ventilated, and the food provided was “wholesome in character, generous in quantity and well cooked.” Most importantly, the girls’ general health was deemed “good” and the girls themselves were described as “strong and plump.” Ultimately, the overall verdict was that the school was severely lacking in certain areas and needed much work done to it. It especially needed more staff because much of the industrial work being performed at the school was “carelessly done.”

The Hadley School was never able to correct its course and was officially turned over to the Children’s Home Society in 1910. The school building was eventually torn down sometime in the mid-20th century.

While the school was not particularly successful, it doubtless played an important role in the lives of the girls sent there to learn. Some girls were returned to their families once it was ascertained those families could resume care, others were adopted by families both within and outside of Indiana. A few went on to attend college. Many married and transferred the domestic skills they learned at Hadley to the running of their own households. And this, of course, was the ultimate goal of the school: To create reverent and hard-working wives and mothers who ensured that the principals championed by the WTCU would endure.

Indeed, the Indiana WTCU soldiered on and would eventually see their many years of diligent temperance work yield results with the adoption of the Eighteenth Amendment in 1920 which banned alcohol sales throughout the country. Prohibition was repealed in 1933 but the organization continued to operate for the rest of the century and remains active to this day.

Sources

Davidson, Joe Harris. “Indiana W.C.T.U. Industrial School for Girls.” Indiana, 1967. (ISLO 371.9 no. 16)

Hendrickson, Francis. “Hoosier Heritage, 1874-1974: Woman’s Christian Temperance Union.” Indianapolis, 1974. (ISLI 178.06 W872h)

“History of the Indiana W.C.T.U. Hadley Industrial School for Girls.” Indiana : Indiana Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, 1894. (ISLO 371.9 no. 9)

Rogers, A.K., Mrs. “Report of visit to Hadley Industrial School for Girls for the Indiana Board of State Charities.” Indianapolis: Indiana Board of State Charities, 1902. (ISLO 371.9 no. 13)

“Woman’s Christian Temperance Union of Indiana Meeting.” Annual meeting of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union of the State of Indiana. (ISLI 178.06 W872c)

This blog post was written by Jocelyn Lewis, Catalog Division supervisor, Indiana State Library. For more information, contact the Indiana State Library at 317-232-3678 or “Ask-A-Librarian.”