The 1920s were an exhilarating and decadent era for Americans. With one devastating World War behind them, they were ready for peace, stability and fun. Businesses boomed, people prospered and modern technologies like radio and cinema exposed individuals to ideas and sensations never before experienced. All these changes had a particularly profound effect on the nation’s young women. They began to chafe against what they perceived as old-fashioned restraints on their behavior and appearance. Beginning in 1922, they could vote. They held jobs, shortened their skirts, wore make-up, smoked, drank alcohol (despite – or because of – Prohibition) and perhaps most shocking of all, they cut their hair and made the stylishly short bob the default hairstyle for women everywhere.

There is much debate over the origin of the bobbed hair fad of the 1920s. Some attribute it to a particular Parisian barber. Others to the 1910s dancer and megastar Irene Castle who shortened her tresses in 1915 for convenience prior to undergoing surgery and a long hospital stay. Another theory attributes the popularity of short hair to the prevalence of Joan of Arc imagery used in propaganda campaigns throughout the first World War, where she was often depicted as having short hair. Whatever its origins, once it took hold among the nation’s young women, it spread rapidly and thoroughly, including here in Indiana. Of course, not everyone approved and the resulting battle over female hair length played out in various newspaper columns throughout most Indiana communities in the 1920s.

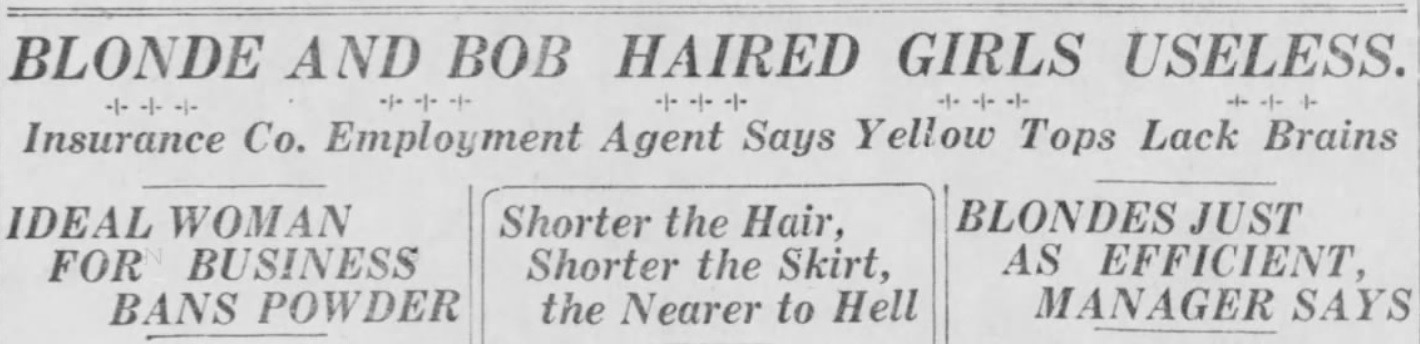

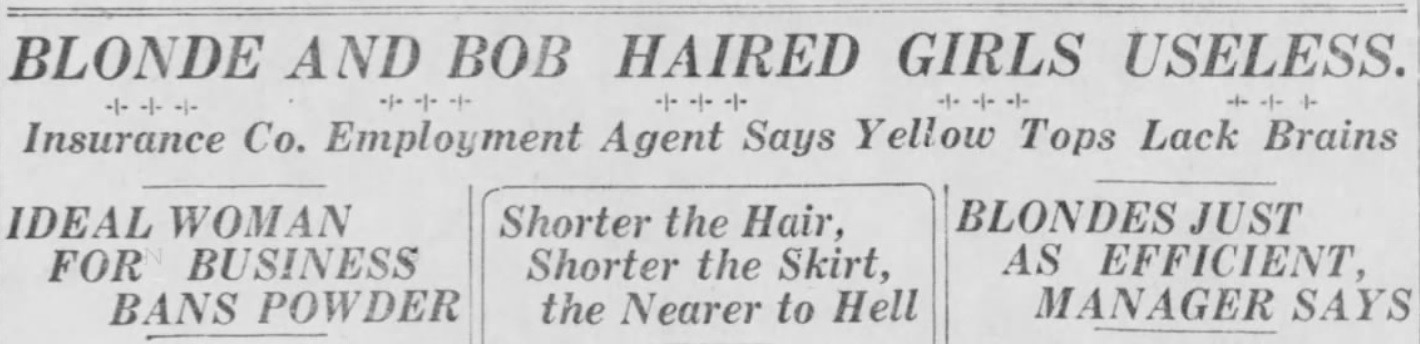

Some businesses refused to hire women with short hair, considering a bob a sign of immorality. Interestingly, in this article shorn locks – a personal decision – is given equal consideration to blonde hair, a genetic condition, although dying hair was also increasingly popular during this time period.

Indiana Daily Times, July 9, 1921.

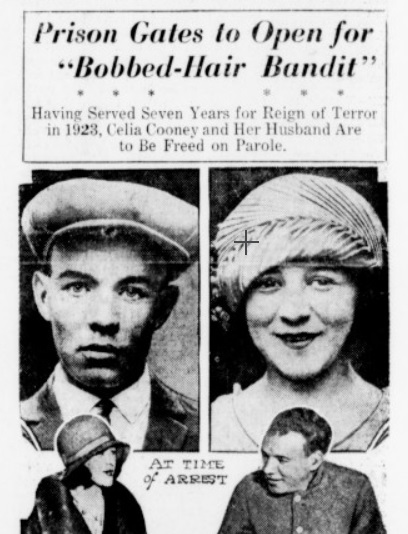

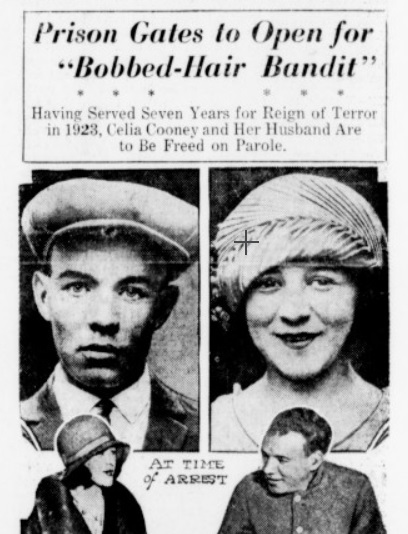

The “loose morals” trope of the bobbed hair phenomenon was underscored by accounts such as this article which gleefully highlights the offender’s hair style in the headline.

Daily Banner (Greencastle), Oct. 27, 1931.

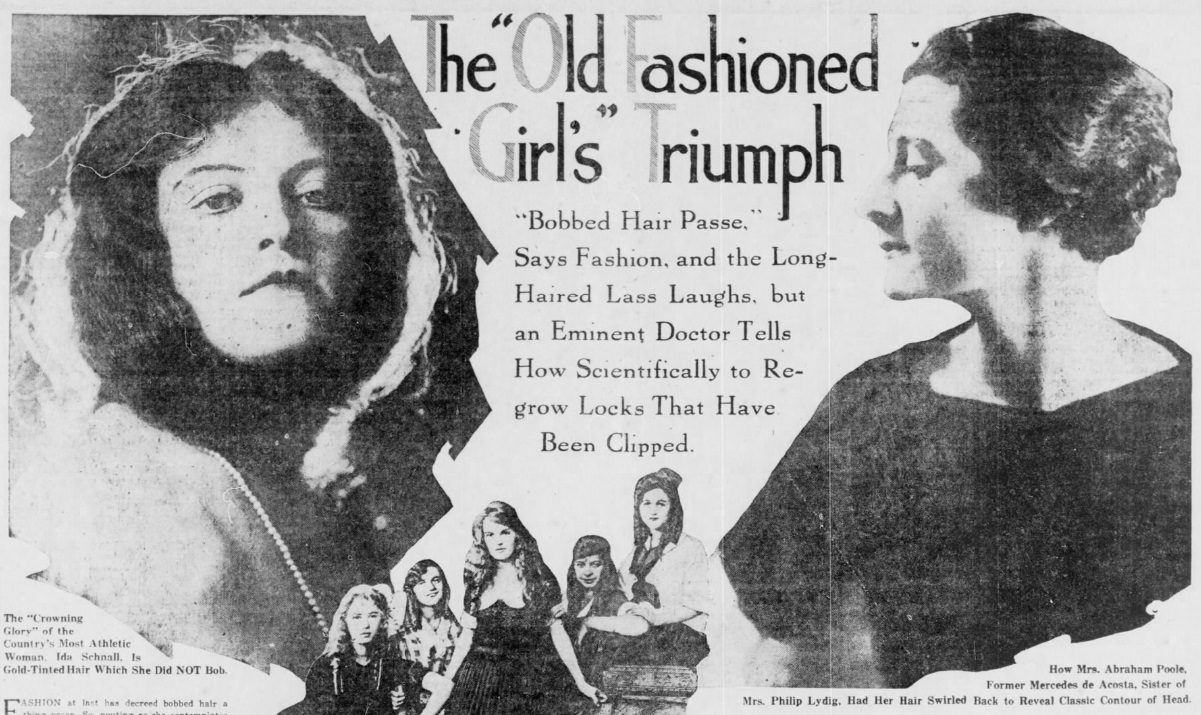

As the bobbed hair craze took over the country, attempts were made to discourage the trend. Articles appeared encouraging women to keep their hair long thus retaining their “crowning glory.” Some articles offered “scientific” advice on how to quickly regrow hair for those regretting their bob. Underscoring many of these articles was the notion that long hair was inherently feminine and that women who deviated from this norm were an abomination of traditional womanhood.

South Bend News Times, Feb. 22, 1922.

Other articles argued that bobbed hair was somehow more expensive to upkeep than long hair. This brief article fails to make an actual argument in support of that thesis but still manages to throw out an inflammatory accusation with the almost certainly fabricated quote “…bobbing does destroy a girl’s personality… we all look like orphan asylum inmates.”

Greenfield Herald, Sept. 20, 1924.

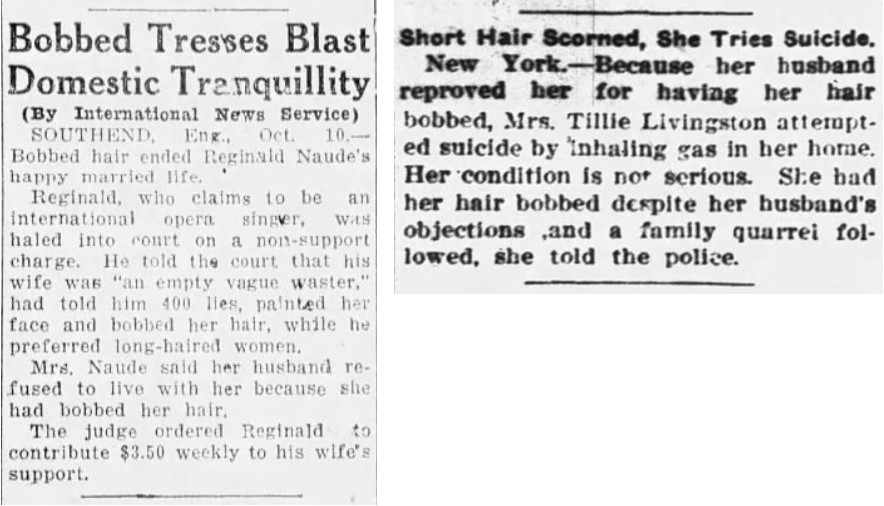

Bobbed hair was used as a scapegoat for more serious social ills such as the dissolution of marriages and even suicide.

Evansville Courier and Press, Oct. 11, 1923. Brown County Democrat, Aug. 24, 1922.

Despite this barrage of negative media, bobbed hair did have its proponents in popular media. Some considered the hairstyle more hygienic and practical, such as the president of the Indiana State Board of Health, although he did use this opportunity to publicly scorn makeup use.

Garret Clipper, April 10, 1924.

While some businesses completely banned bobbed hair among female employees, others allowed it, albeit with some reluctance.

South Bend News Times, Aug. 14, 1921.

Still, others pointed out that women’s appearances and fashions have been constantly changing throughout recorded human history and that short hair and short skirts were not necessarily a new fad, but a return to an older social norm.

Evansville Courier and Press, Oct. 8, 1923.

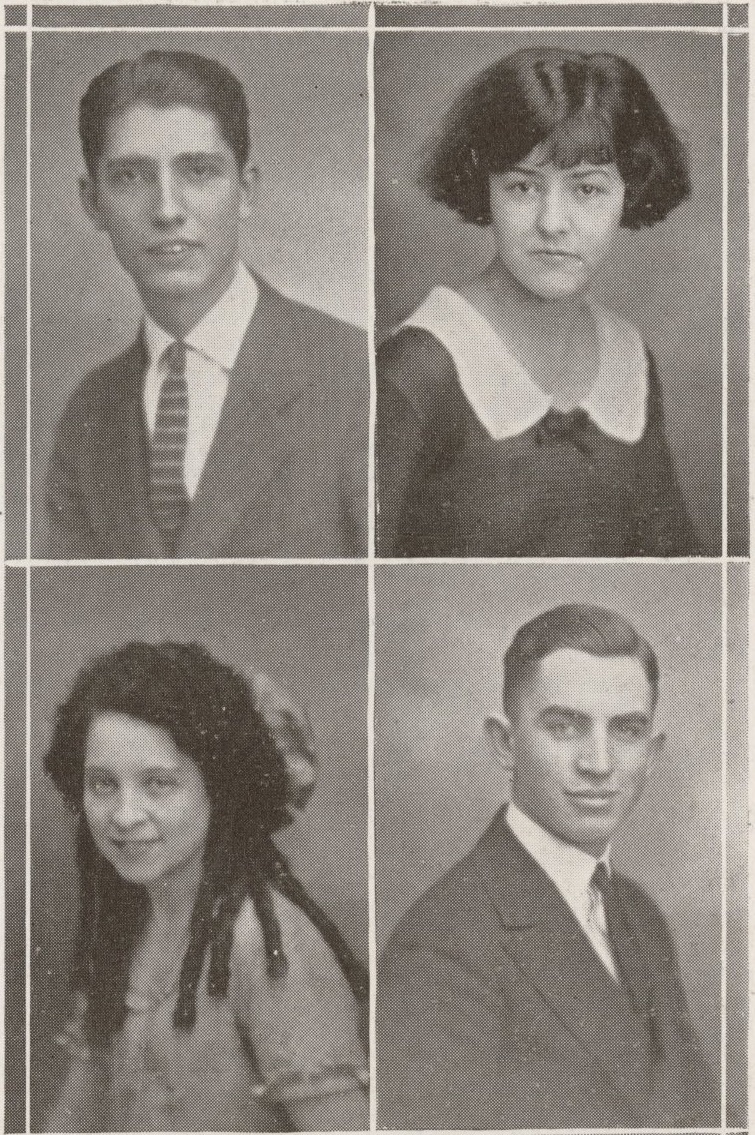

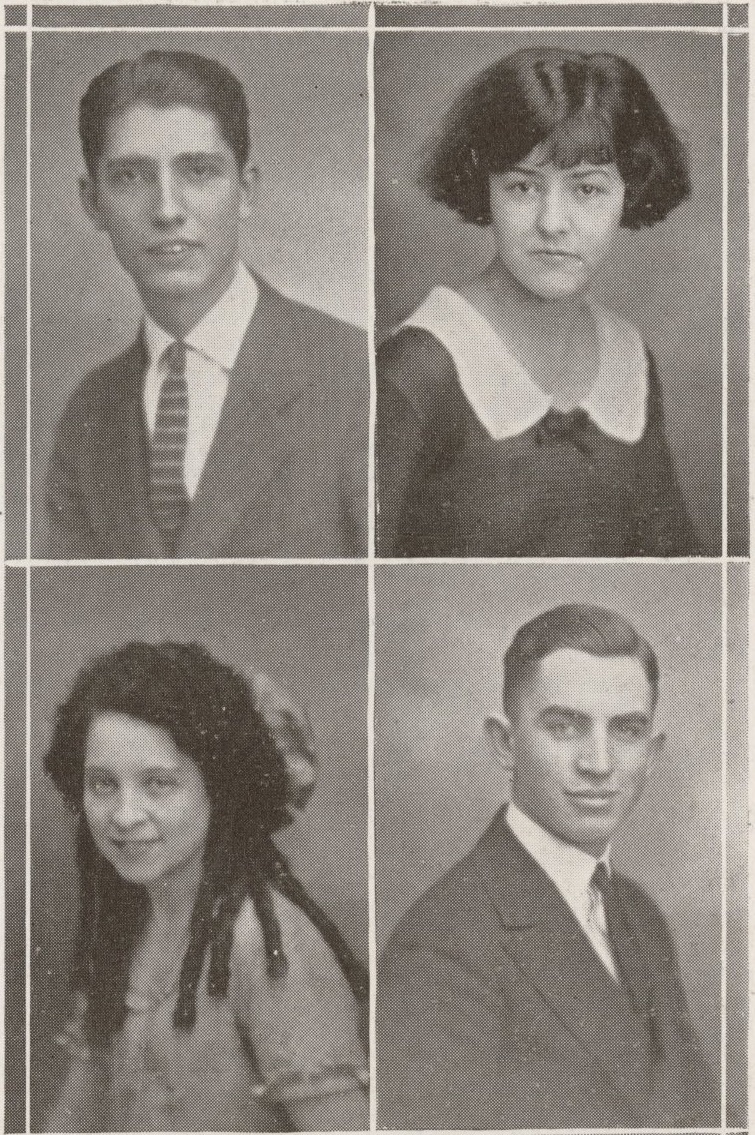

But perhaps the strongest proponents of bobbed hair were the millions of young women who gleefully sliced off their long locks. For many it was a statement of personal choice and preference, a symbol of modernity and, as with voting, a chance to be citizens on their own terms.

Pictures of unidentified Hoosier women with bobbed hair circa the 1920s. From the Indiana Picture Collection, Rare Books and Manuscript Collection.

The trend became so prevalent, that by the middle of the 1920s it was very difficult to find any young women with long hair. Indeed, one occasionally finds them in the pages of local high school yearbooks. One has to wonder, how did these girls feel about their long tresses? Were they forbidden to cut their hair by their parents? Did they simply like having long hair? Or maybe they sensed that a daring and scandalous trend is no longer daring and scandalous when absolutely everyone does it and therefore by refraining, they signify themselves as unique and rebellious?

A long-haired holdout from Kokomo High School, class of 1923 (ISLI 379 K79 1923).

The social propensity to police women’s appearances did not end with the bobbed hair fad of the 1920s. While fashion dictates throughout the rest of the 20th century caused hair to lengthen again, the bob has remained a standard for millions of women everywhere. Public outrage gradually moved away from hair length to other considerations such as the wearing of pants, bikinis, crop tops, leggings, tattoos, etc. While contemporary women have a great deal more choice when it comes to how they appear and hair length is largely considered a simple personal choice and not a brazen social statement, it is helpful to remember that these have been hard-fought battles.

This blog post was written by Jocelyn Lewis, Catalog Division supervisor, Indiana State Library. For more information, contact the Indiana State Library at 317-232-3678 or “Ask-A-Librarian.”