A recent acquisition of the Rare Books and Manuscripts Division has proved a charming read: “The Diary of Margaret Elliott” (V580), a sophomore at Purdue University in 1925. Born Nov. 29, 1905 in Logansport, she spent most of her life in Lucerne in Cass County, where she still lived when she died on Aug. 22, 1974 at IU Medical in Indianapolis.

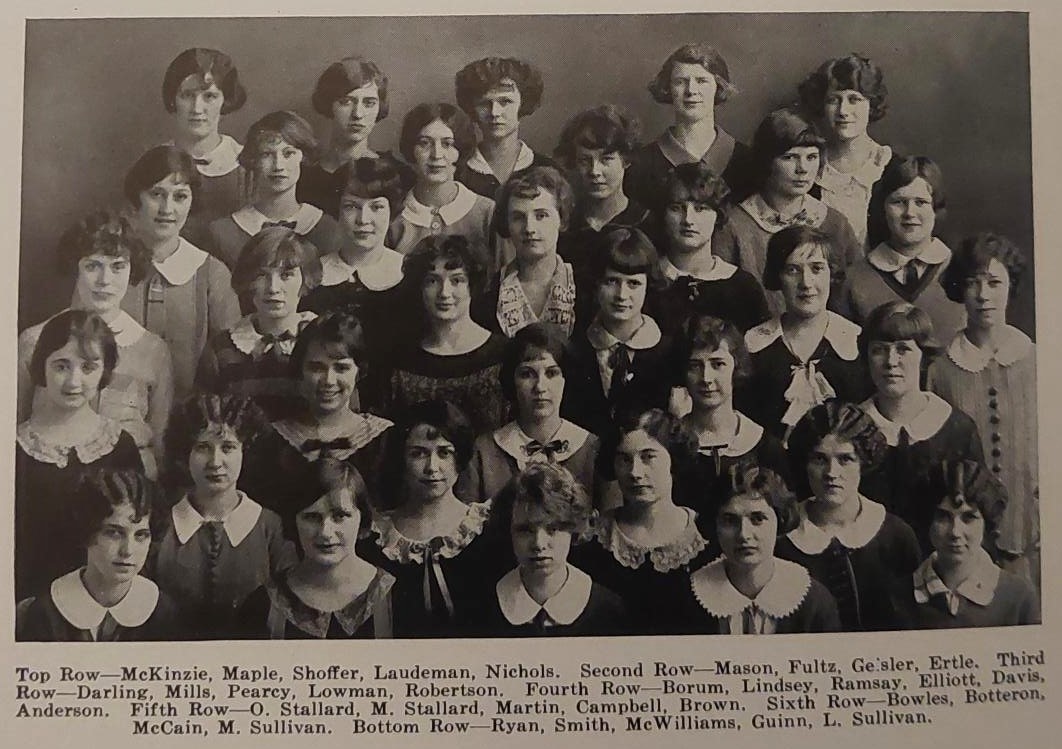

Elliott, who attended with her sister Lottie, was an exceptionally engaged student both academically and socially. In addition to pledging Alphi Chi Omega, she was a member of the Philalethian Literary Society, a women’s society founded in 1877; the Y.W.C.Q; and the Purdue Girl’s Club. She speaks about classes in English, French, Psychology, Physics, History and Education. She was of the first class to have an honor roll at Purdue known as the “distinguished students,” and her name is included among the ranks.

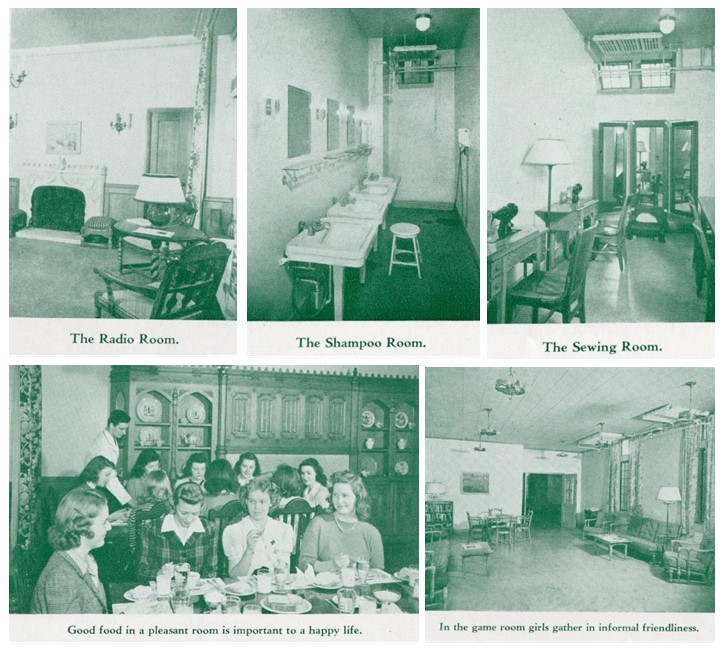

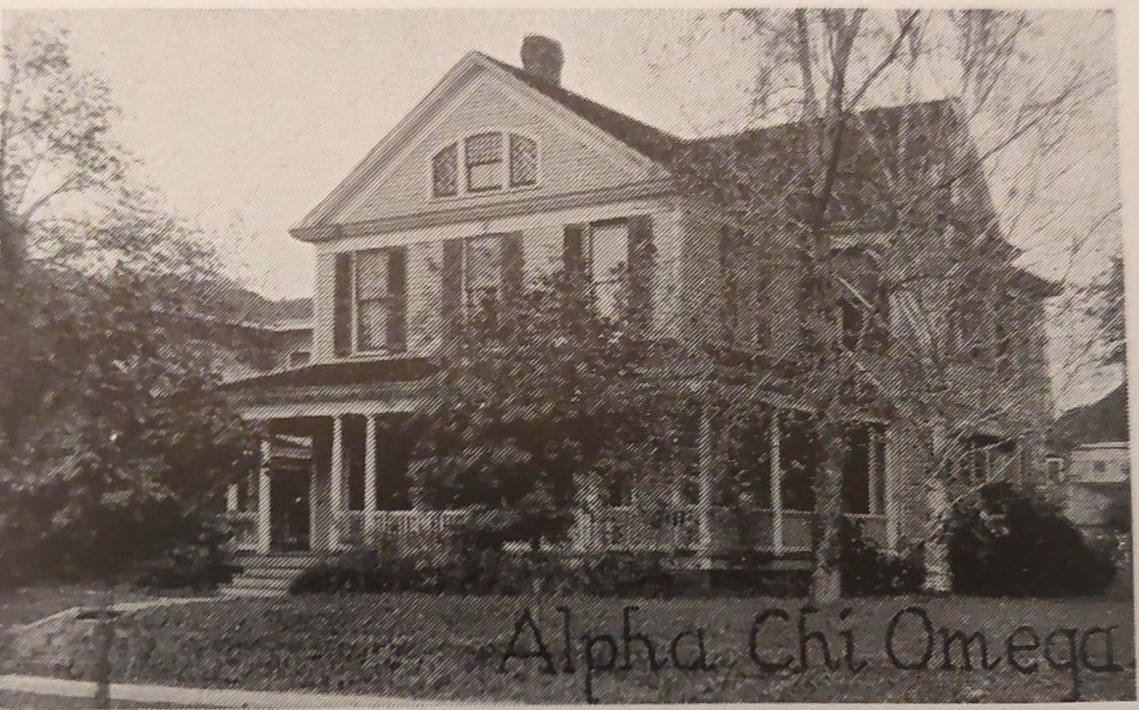

Throughout the diary, she only ever refers to her place of residence as “the house,” but it can be assumed to be the Alphi Chi Omega sorority house. The Purdue Ladies Hall, demolished in 1929, would have still been standing at the time of her tenure, but would surely not have been referred to as a “house.” The diary documents the many social events of Greek life in Purdue in this lively period, as well as the dress and behavior – including drinking by some of her male classmates – among the students.

Photo of the Alpha Chi Omega sorority house from the 1925 Debris, Indiana Serials, ISLI 378 P985d, 1925.

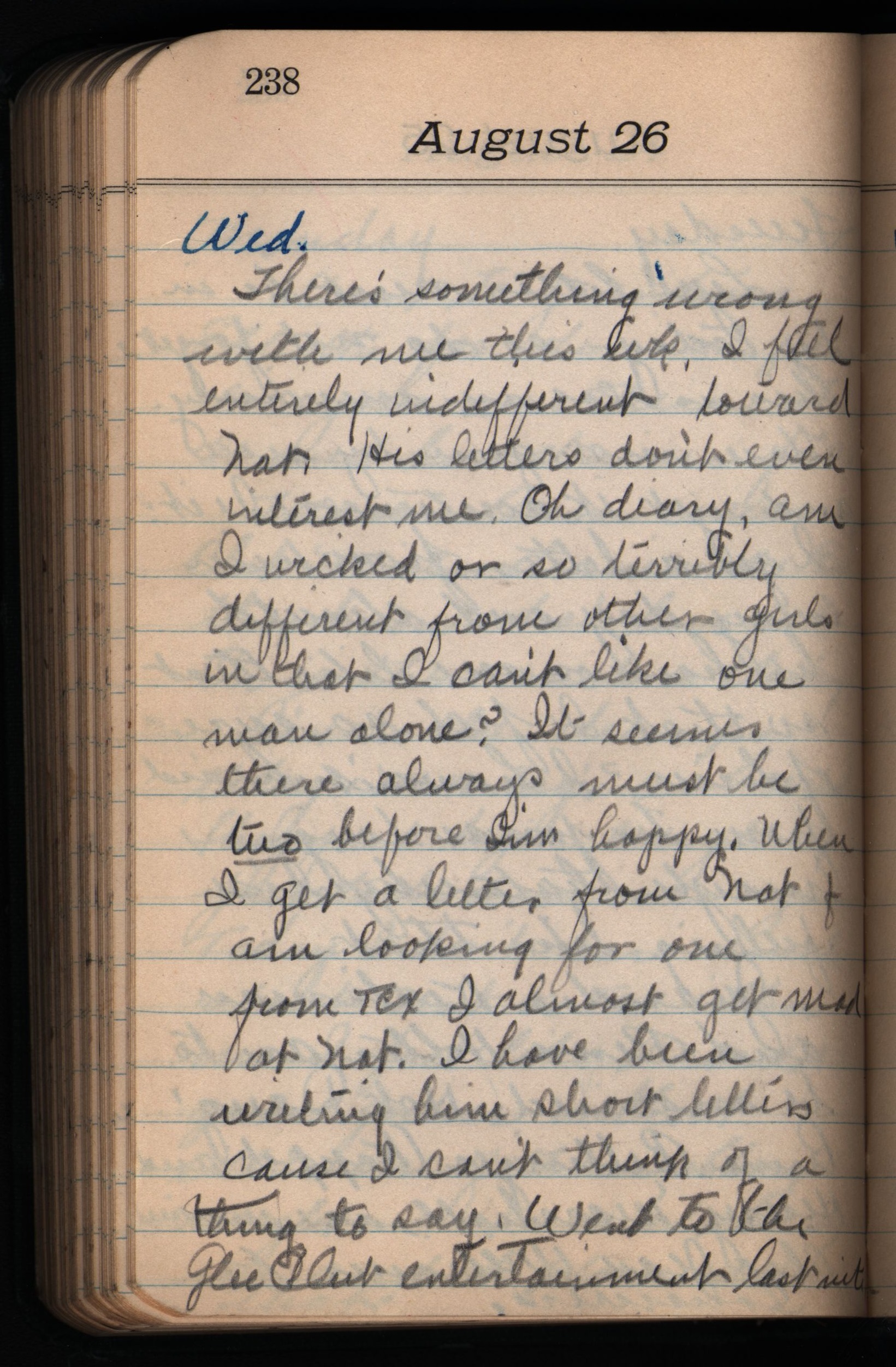

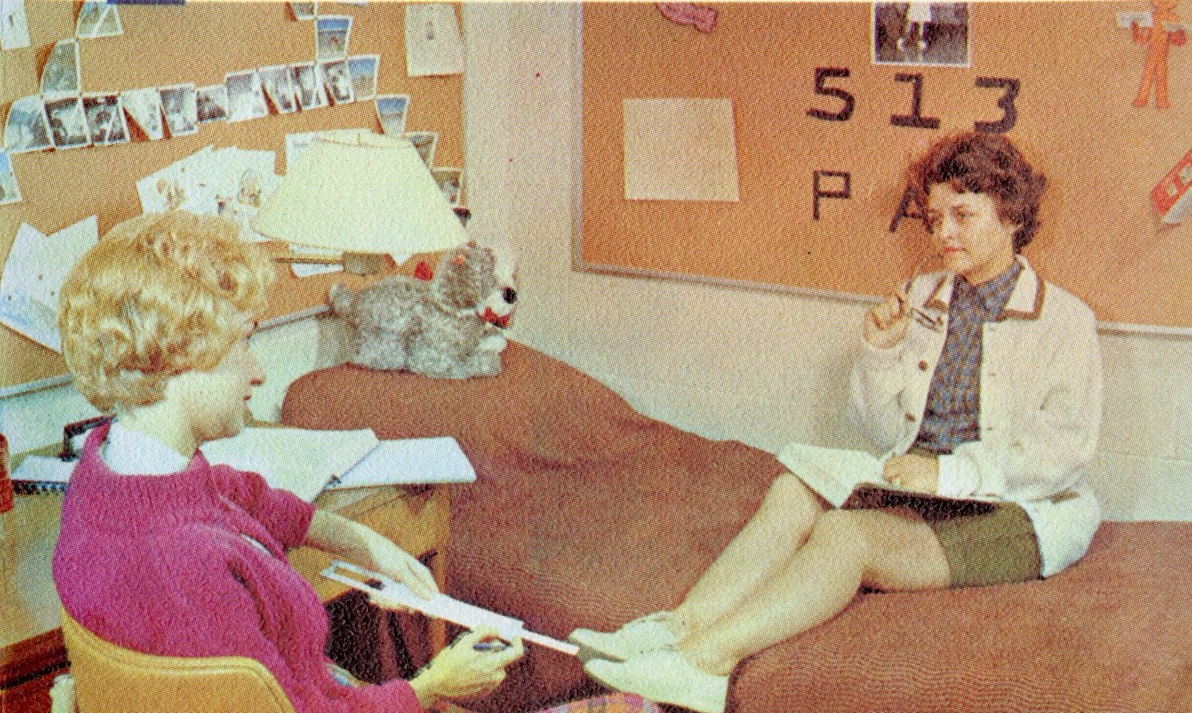

Her account of college life is still in many ways relatable: staying up until 3 a.m. with boys and cramming for tests. In April she writes: “Too much high, fast, hard living!” and in August: “Oh diary, am I wicked or so terribly different from other girls that I can’t like one man alone? It seems there always must be two before I am happy.”

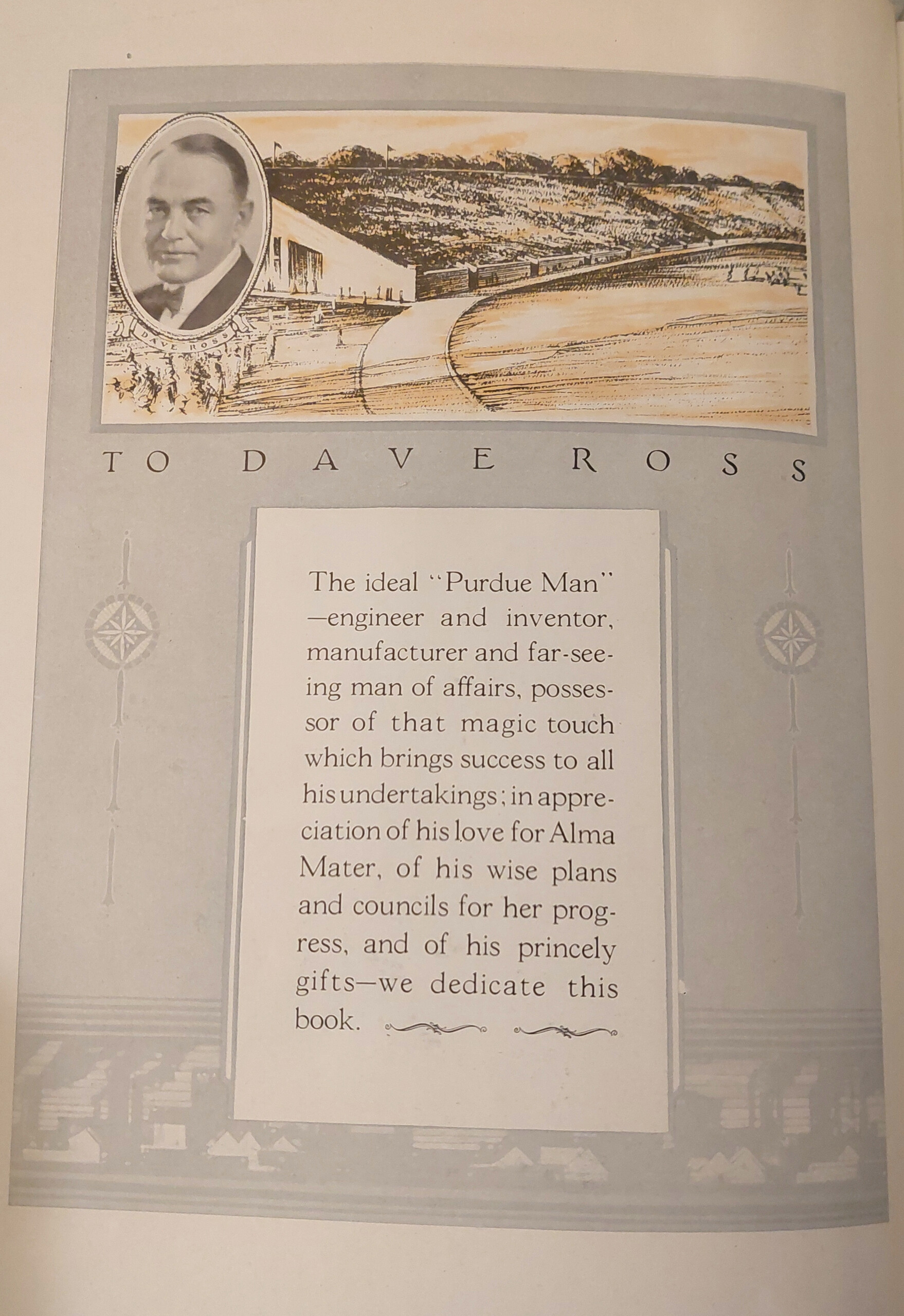

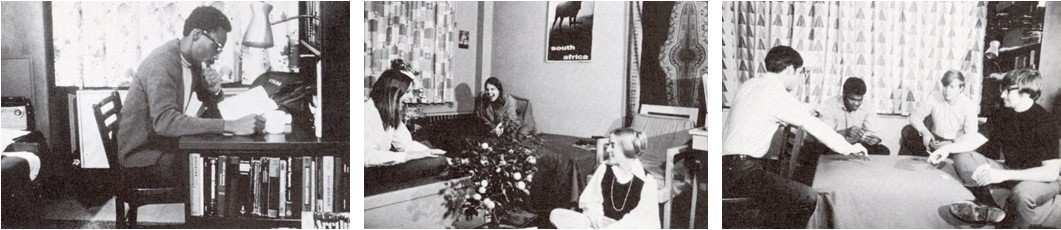

Indeed, the date juggling – sometimes more than one in the same night – with the passionate “Tex” and reliable “Nat” make this volume a page-turner. Though the senior portrait of Margaret does not evoke that of the “New Woman” flapper ethos, she certainly was a liberated college student by modern standards – coming and going as she pleased and seemingly enjoying the company of anyone she chose. It did not appear that her place of residence had rules about having men over, or at least they weren’t heavily enforced. Purdue admitted women as of 1875 and so her presence was not have been particularly novel; however, she did not exactly embody the traits of the “ideal ‘Purdue Man’” as outlined in the 1927 Debris, Purdue’s yearbook. However, she is a great reminder that Purdue has been important to Hoosier education for more than engineering – and for more than just male education.

Seen here in her sorority group photo, she has the more quintessential flapper bob. From the 1925 Debris, Indiana Serials, ISLI 378 P985d, 1925.

The diary is a record of a young woman who was not ready to commit to a life determined by her male suitors, each of which talked about taking her back home with them. She did avoid settling down for a period even after she graduated from Purdue, only finally marrying in 1935. This ended her career as a school teacher of English and History at schools in Tipton township, including the old Walton High School, which became Tipton Township High School. She resigned from Delphi-Deer Creek Township High School in Delphi – also long ago consolidated – a month after she married Earl D. York, born on Oct. 17, 1900, from North Grove. York worked for the Foreign Sales office for Texaco, and died on Dec. 11, 1990.

Though we have no evidence of whether quitting teaching was something she did wholeheartedly, it is hard not to assume that it was at least bittersweet for her. However, there is evidence that this educated dreamer lived a full life and did some traveling, with passenger manifest showing that she took trips to Panama and England and that, like many Hoosiers, she spent time in Florida.

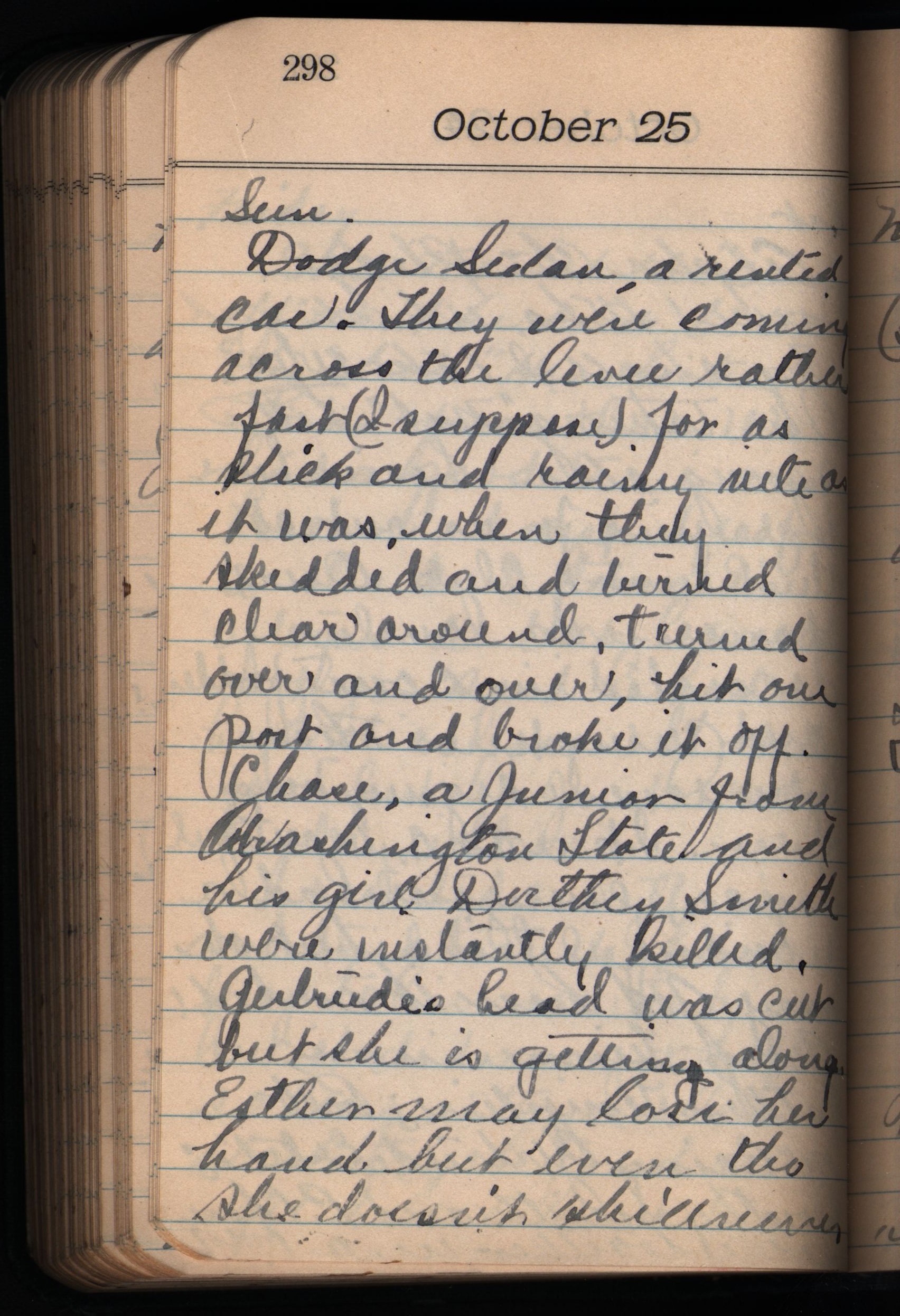

Diaries can be hit and miss in terms of their research value and whether they provide any real insight into the time periods they document, depending heavily on the style of the writers who penned them. Not every diary can be saved, and many of them touch on only the most salient points of a day, often serving more as a daily calendar that doesn’t offer much even for piecing together family histories. The particular diary offers much in that it traces many ups and downs of both herself and fellow students. Her account of the 1925 automobile accident that killed two of her classmates, for instance, included a newspaper clipping slipped in between the pages as well as descriptive account of the accident and subsequent funeral.

Her love of literature also colors the document, as she includes numerous quotes from writers such as Tennyson, Kipling and many more relatively forgotten writers who were popular at the time, as well as prominent writers on women’s issues including Sarah Grand and Margaret Widdemer. An afternoon could be spent happily just identifying the quotes in her books, but one Honoré de Balzac quote sticks out: “Marriage is a matter of one’s whole life; love is a matter of pleasure.” It seems Margaret had both, as well as a rich internal life – a life well lived!

This post was written by Victoria Duncan, Rare Books and Manuscripts supervisor.