Football is as integral a part of American Thanksgiving as turkey and pumpkin pie. Indeed, both Thanksgiving as a national holiday and the game of football originated around the same time. President Ulysses S. Grant established the official holiday in 1870, a mere year after Rutgers University defeated Princeton 6-4 on Nov. 6, 1869 in what is widely considered the first match of American football ever played. The game quickly grew in popularity, particularly among American universities, and as popular trends usually do, it eventually found its way to Indiana.

A fictionalized account of an early Indiana football game can be found in the short story “Butler vs. Purdue: A Thanksgiving story,” written and published by George S. Cottman, a prolific historian and author who ran a printing press out of his home in Irvington. The story opens in Indianapolis on Thanksgiving morning 1890 with a young woman named Esther pleading with her father to take her to a local football match between Butler University (whose campus was located in the Irvington neighborhood at the time) and Purdue University. Her father, a stern military man dubbed Colonel Cannon, initially refuses and chides his daughter’s interest in the sport. Like many other older adults at the time, he holds the notion that football is an unusually violent sport and unworthy of being associated with institutions of higher learning. With little self-awareness he declares “If I’d a boy in college… who spent his time tussling about in the mud when I was paying for the cultivation of his brains I’d cudgel him till he took to his bed. Is that what they go to college for – to break bones and mash each other flat?”

After further cajoling and some overly dramatic tears from Esther, he relents and they make their way to the YMCA athletic park, located at the time in the Arsenal Heights neighborhood, just east of downtown. The game has already started and Butler is losing to Purdue 10-0. Esther, who incidentally is also being courted by a football player from Butler, is in despair at how dominant the Purdue team seems. “What great big ugly things they are! It’s too much to expect our boys to stand against a lot of elephants!”

She is equally disgruntled with the Purdue fans who have made the long trip to Indianapolis to cheer on their team. “Hear those horrid people. I hate to see country jakes come in and try to take the town. If they love to bellow so why don’t they go out in the woods around Lafayette and do it to their hearts content.” The snub “country jakes” is a jab at Purdue’s notoriety as an agricultural school and belies a distinct snobbery at the rural-urban cultural divide which was likely a common sentiment for city-dwellers such as Esther.

In what today would seem a bit of a gendered role reversal, Esther spends much of the game explaining the sport to her befuddled but increasingly interested father. The game she describes is quite different but still recognizable to the sport in its modern form. The match consists of two 45 minute innings. Touchdowns are worth four points and conversion kicks add another two. Teams have three downs to advance the ball five yards. Colonel Cannon’s martial sensibilities are particularly delighted by offensive plays employing the flying wedge formation, which is unsurprising considering the early football tactic was based on a centuries-old military maneuver (and then quickly banned in 1894 because it caused so many injuries).

As this is a story written by an Irvington resident, it predictably ends happily for Butler. The Butlers (the nickname Bulldogs was not adopted until 1921) rally in the second inning and ultimately win the match 12-10. The Purdues (the term Boilermaker wouldn’t make an appearance until the following year in 1891) fail to get any more points on the board. Colonel Cannon has been converted to football fandom and Esther can now safely invite her beau to dinner without dooming him to her father’s archaic notions on collegiate sports.

While Esther and Colonel Cannon are fictional characters, this game really did happen and was held Nov. 27, 1890. It was the state championship game for Indiana football and extensive coverage of the match appeared in multiple Indianapolis newspapers.

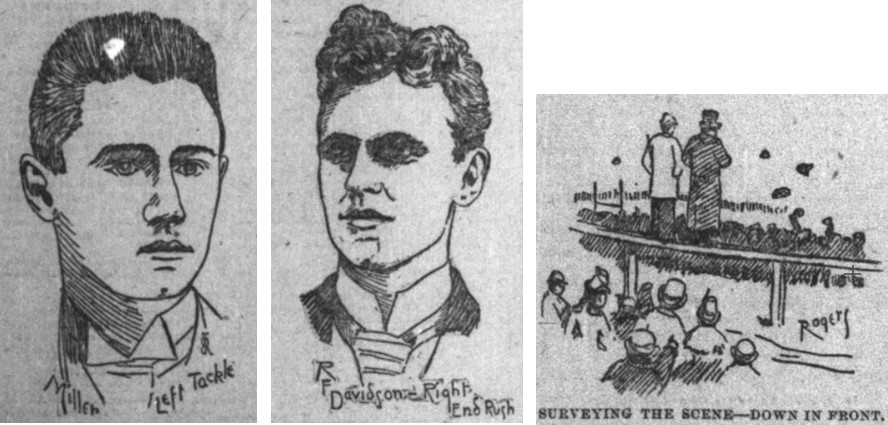

While 1890 was a bit too early for photographs of the event to be printed in local papers, it was deemed an important enough event by the Indianapolis News to dispatch an artist to draw illustrations for the story.

Adding to the day’s drama was the fact that a rowdy post-match victory drive through the streets of Indianapolis resulted in a large wagon referred to as a “tally-ho” being overturned and seriously injuring several football revelers, though all seem to have survived the ordeal.

Football continues to be an important part of Thanksgiving in Indiana, especially for Purdue. While the school no longer plays Butler in football, their annual Oaken Bucket game against in-state rival Indiana University is usually played near Thanksgiving. The weekend following Thanksgiving is also when high schools from throughout the state converge on Indianapolis to battle for various football championships. And of course, millions of Hoosiers will tune in to watch professional football from the National Football League, a holiday tradition that dates back to the NFL’s first Thanksgiving game held in 1934.

This blog post was written by Jocelyn Lewis, Catalog Division supervisor, Indiana State Library. For more information, contact the Indiana State Library at 317-232-3678 or “Ask-A-Librarian.”