Over the course of the 20th century, innovations in technology revolutionized the lives of rural dwellers throughout the United States. Many authors documented these changes and the effects they had on rural society. Among them were Hoosier authors Gene Stratton-Porter and Rachel Peden, who wrote about their own everyday lives and experiences. Writing in Adams County, Stratton-Porter documented the natural world in novels and non-fiction alike. Her work showed the effects of the demand for increased farm acreage as woods were felled and swamps drained to create new farmland. Peden, a Monroe County resident, wrote a long-running column for the Indianapolis Star as well as several books. Writing from the mid-1940s to the mid-1970s, she captured the end of one era in rural life and the beginning of another.

Advance Rumely combine-harvester, ca. 1920; Advance Rumely trade catalog, Indiana Pamphlets Collection, Indiana Division, Indiana State Library

One of the greatest technological innovations of the twentieth century for farmers was the mechanization of farm equipment, which made field work faster and easier. With the increased productivity of the new farm equipment, farmers could work larger acreages, enabling them to realize larger harvests and thus larger incomes. They often reinvested their money in their farms, purchasing more and bigger farm equipment, adding electricity to their homes and barns and increasing the types of equipment and appliances they owned.[1] The new technology also changed the farm equipment industry, as improvements to the equipment kept the farmers coming back to buy the latest machines.

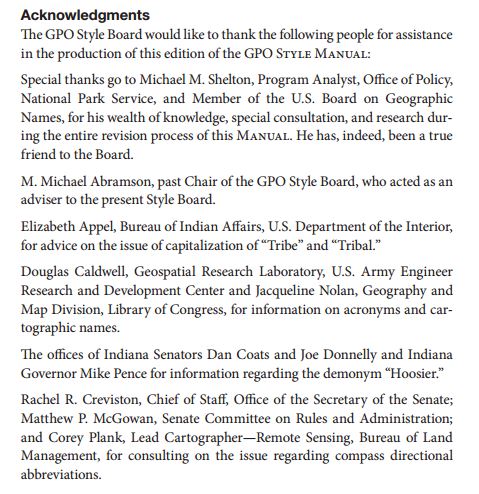

Michael O’Halloran by Gene Stratton-Porter

Despite the practicality of the farm machinery, some farm wives resented having to roll their extra income into the purchase of tractors and corn pickers while they had to do without modern appliances in their homes. Early machinery purchases accentuated the traditional gender roles, as the male head of the household often controlled the family expenditures. Stratton-Porter addressed this inequality in “Michael O’Halloran,” in which Michael explains to a farmer that:

“if there was money for a hay rake, and a manure spreader, and a wheel plow, and a disk, and a reaper, and a mower, and a corn planter, and a corn cutter, and a cider press, and a windmill, and a silo, and an automobile—you know Peter, there should have been enough for that window, and the pump inside, and a kitchen sink, and a bread-mixer, and a dish-washer; and if there wasn’t any other single thing, there ought to be some way you sell the wood, and use the money for the kind of summer stove that’s only hot under what you are cooking, and turns off the flame the minute you finish.[2]”

Although somewhat exaggerated for dramatic effect, Stratton-Porter’s statement illustrates the resentment women felt when their desires appeared to be of secondary importance within the family. Even women who understood the need for machinery thought that the emphasis farm experts placed on the need for the latest machinery was ridiculous. What farm women really wanted were electric appliances to make their housework more convenient and allow them a better standard of living. Through rural electrification projects, over 90 percent of farms in the United States had electricity by 1960, up from 10 percent in 1935.[3] Like farm women across the country, most Hoosier women got electricity during this time. For these women, finally getting what they had wanted and waited for so long was an “unbelievable dream.”[4]

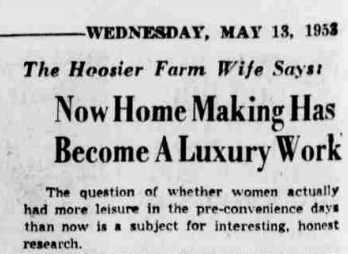

Rachel Peden’s “The Hoosier Farm Wife Says” column documented rural life and entertained readers of the Indianapolis Star for nearly 30 years.

For farm wives, their new household tools brought one major advantage: less time spent on housework and more time spent on leisure. Prior to electrification, women spent much of their day preparing meals on a wood-fueled stove, doing laundry with a washboard or hand-cranked wringer washer and mending clothes by hand or with a treadle sewing machine. Their housework was labor-intensive and very hands-on. By purchasing appliances to aid them in their work, rural women bought more free time for themselves. They could also multitask more effectively. For example, automatic washing machines allowed women to put their laundry in the machine and then go do other tasks while the clothes were washed.[5]

At first, modern conveniences were wonderful luxuries. As time progressed, however, women came to view their appliances as necessities.[6] They described their appliances as something they could not live without. Although some women felt that their appliances were making them lazy and causing them to complain about minor inconveniences, they also overlooked the fact that this process of the normalization of luxury occurred throughout the past. The wringer washer and wood stoves that twentieth century farm women abandoned were once considered great luxuries by their grandmothers and great-grandmothers, accustomed as they were to washboards and open hearths.[7]

As farming became more mechanized, specialized, and commercialized, the higher expenses required to keep up with the technology caused many farmers to give up farming and seek other employment.[8] For those who stayed, the technological changes led to less cooperation among members of rural communities as combines and store-bought food replaced shared tasks such as harvesting or butchering. As rural communities and rural work changed, rural dwellers reported a loss of the sense of community that they had shared in the past.[9]

Hoosier communities were not immune to this trend. Before mechanization, the men of the community would get together and harvest each farmer’s crops, each man bringing his own wagons, horses and hand tools, while the women gathered to prepare meals for the workers.[10] Despite having more social opportunities in the latter part of the twentieth century due to improved cars and roads and more leisure time to join clubs and other social groups, farm women still regretted the loss of the annual harvest time. Harvest lingered in women’s minds as something good that they had lost because working together built community in a way that a social club never could. When the members of a rural community engaged in a difficult, yet essential, task that no one family could accomplish by itself, the members of the community learned to rely on one another in a way developed only through hard work toward a common goal. This spirit of interdependence created community between often-isolated rural dwellers and created a web of social support and goodwill as farm families knew they could turn to their neighbors in times of trouble or hardship.

By the end of the twentieth century, many rural dwellers expressed fond feelings toward the “good old days,” particularly in reference to what they saw as a simpler rural life before machines, off-farm jobs and commercial farmers. Much of this nostalgia stemmed from their memories of the past and things they missed from their old lifestyles. Although no one missed the harder work of the past, many farm women saw the complications and losses of the modern world and wanted to return to the simpler times of their youth.[11]

This blog post is by Jamie Dunn, genealogy librarian. For more information, contact the Genealogy Division at (317) 232-3689 or send us a question through Ask-a-Librarian.

[1] Rachel Peden, “Tractor Makes Possible Luxury of Riding Horse,” Indianapolis Star, January 15, 1964, page 12.

[2] Gene Stratton-Porter, Michael O’Halloran (New York: Doubleday, Page & Company, 1915), 356.

[3] David B. Danbom, Born in the Country: A History of Rural America (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006), 222. United States Department of Agriculture, “Rural Electrification,” United States Yearbook of Agriculture, Washington, D.C., 1940.

[4] Rachel Peden, “Summer Lightning Jumps out of the Cold Storage,” Indianapolis Star, February 12, 1965, page 14.

[5] Rachel Peden, “Now Home Making Has Become a Luxury Work,” Indianapolis Star, May 13, 1953, page 14.

[6] Katherine Jellison, Entitled to Power: Farm Women and Technology, 1913-1963 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1993). The entire book documents the shift in perspective from luxury to necessity.

[7] Rachel Peden, “Man’s History Written in Tools of Yesteryear,” Indianapolis Star, January 6, 1964, page 14.

[8] Rachel Peden, “Progress Arrives as Farmers Depart,” Indianapolis Star, February 22, 1961, page 14.

[9] Mary Neth, Preserving the Family Farm: Women, Community, and the Foundations of Agribusiness in the Midwest, 1900-1940 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995), 181.

[10] Rachel Peden, “Silo Filling Day is Red Letter Occasion,” Indianapolis Star, September 30, 1947, page 14.

[11] Rachel Peden, “Too Much Efficiency is Mighty Depressing,” Indianapolis Star, August 18, 1958, page 12.

Indiana is home to a deep and rich literary heritage stemming from our long-ago classic writers like Gene Stratton-Porter and James Whitcomb Riley to the big names of the ’60s and ’70s – Kurt Vonnegut, Mari Evans, Etheridge Knight and many others – all the way up to today, where everyone knows names like John Green and Meg Cabot. Additionally, characters like Garfield, Raggedy Ann and Andy, Clifford and Little Orphan Annie are all Hoosier creations. It’s impossible to keep track of a list of Indiana writers because new ones emerge and succeed daily. Today, Maurice Broaddus is writing Afrofuturist science fiction. Ashley C. Ford writes about race and body image. Kaveh Akbar’s poetry has appeared in The New Yorker. Kelsey Timmerman’s investigations lead to books about responsible consumerism. What draws all these voices together? Being from Indiana. Being Hoosiers.

Indiana is home to a deep and rich literary heritage stemming from our long-ago classic writers like Gene Stratton-Porter and James Whitcomb Riley to the big names of the ’60s and ’70s – Kurt Vonnegut, Mari Evans, Etheridge Knight and many others – all the way up to today, where everyone knows names like John Green and Meg Cabot. Additionally, characters like Garfield, Raggedy Ann and Andy, Clifford and Little Orphan Annie are all Hoosier creations. It’s impossible to keep track of a list of Indiana writers because new ones emerge and succeed daily. Today, Maurice Broaddus is writing Afrofuturist science fiction. Ashley C. Ford writes about race and body image. Kaveh Akbar’s poetry has appeared in The New Yorker. Kelsey Timmerman’s investigations lead to books about responsible consumerism. What draws all these voices together? Being from Indiana. Being Hoosiers.