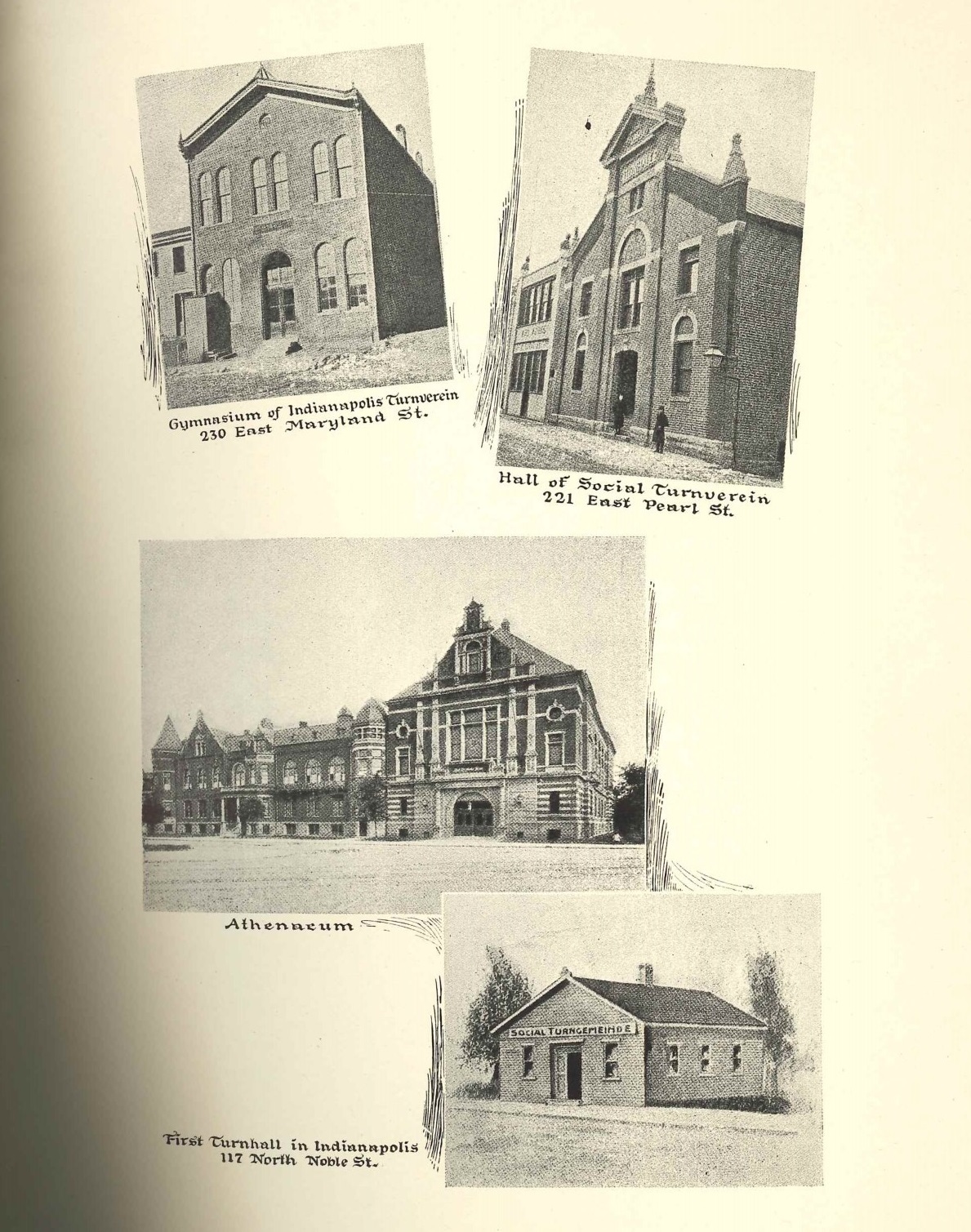

The book “German Settlers and German Settlements in Indiana; a Memorial for the State Centennial, 1916” was written to celebrate German Americans in Indiana for the state’s 100th anniversary. Yet, by 1917, much had changed. The United States had entered World War I on April 6, 1917 and Germans in the country were under new scrutiny.

A Spy is Born

In 1917, an idea was birthed at Indiana’s doorstep in Chicago by Albert M. Briggs, a wealthy businessman. Briggs became concerned about the abilities of the Department of Justice’s Bureau of Investigation to handle the demands of their jobs; so he started a volunteer group of fellow businessmen to drive Bureau of Investigation agents in need of automobile transportation. The group, known as the American Protective League, eventually donated motor vehicles to the Bureau.

The gift of the automobiles opened the door to Briggs making a proposal to the chief of the Bureau that the American Protective League further assist the Bureau by looking for German spies.

Approval was given on March 20, 1917. Bureau of Investigation agents were informed that a volunteer committee was being formed to co-operate with the department for gathering information of those foreign persons unfriendly to the government. The American Protection League would provide information to the agents at the agents’ request and would also gather and provide information on their own volition.

The American Protection League’s day-to-day concerns involved tracking down draft dodgers – in the slang of the time, known as slackers – and German spies ensconced stateside. Specifically, the American Protection League was concerned with enemy aliens, first-paper aliens (i.e., those Germans that had filed their intention to become a naturalized citizen), pro-German “radicals,” native-born Germans, naturalized Germans, possible spies or German agents and pro-German applicants for government positions.

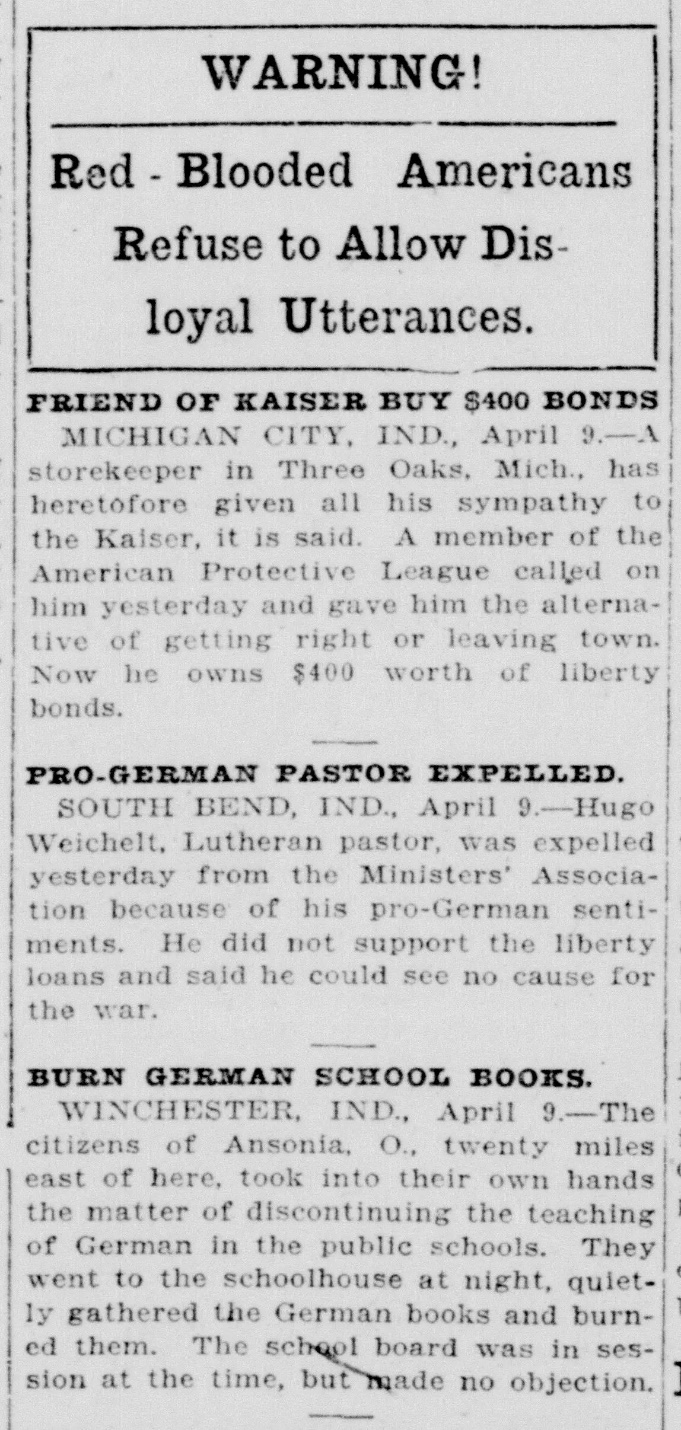

To achieve their many and varied goals, since they had no legal or official authority, agents would sometimes tar and feather suspects, drive the suspect out of town, burn down a suspect’s home or lynch the suspect. Complaints were made to the Attorney General’s Office that accused the American Protective League of wiretapping, illegal arrests, extortion, kidnapping, rape and murder.

Over concerns by the Attorney General that the American Protective League with their vigilante tendencies had violated individual rights – and since the war was over – the American Protection League was shut down and disbanded by the Federal Government in February of 1919. However, the American Protective League unofficially kept the hate alive by easily transferring the hatred from German Americans to Russian Americans suspected of being Bolsheviks.

Good Old Hoosier Hostile-ality

During World War I, all over the nation, anti-German sentiment was seen as patriotic, and Indiana was just as patriotic as any other state. In the Hoosier state, anti-German sentiment included the cessation of teaching German in schools, the death of German newspapers and the suspicion of German names.

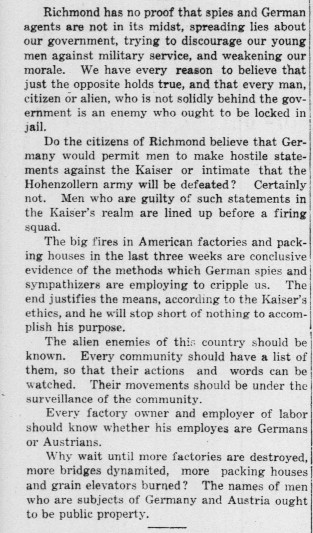

The Hoosier state saw German spies everywhere, as demonstrated by this editorial from the Richmond Palladium newspaper:

In Hammond, a girl turned in her boyfriend to the police whom she suspected of being a German spy; he also had a wife in Chicago.

German Hoosiers wrote letters to their local newspapers decrying their innocence of espionage.

Even Kurt Vonnegut’s grandmother Nannette Vonnegut was spied on by the family’s chauffeur.

The American Protective League in Indiana

American Protective Leagues were formed in many Indiana communities; including Howard County, Huntington, Elkhart, Evansville, Lake County and, of course, Indianapolis.

The Indianapolis Protection League boasted of the internment of 50 alien enemies and the handling of over a thousand cases.

The work of the Indiana American Protective League can be found in the American Protection League’s authorized history: “The Web – A Revelation of Patriotism:”

“Though wireless scares are most frequent on the seaboard, almost every city can boast several of them. An Indianapolis operative thought he had discovered certain wireless antennae on the property of a family with a German name. A pole was found fastened to the roof of a shed, wires being used to connect it with the attic of the house. It was noticed that the attic had close-drawn blinds, whence lights were occasionally seen. The whole thing simmered down to an outfit put up by some young men to practice telegraphy.”

And

“On this same expedition we stopped to see the Lutheran minister as private citizens, and told him that the people of Jasper County wanted no more German preaching and no more German teaching in the schools; also they would like to see Old Glory floating from the mast-head. We told him also that this was the last time that he would be notified. In about three hours we returned that way and stopped again. Old Glory was floating at the mast-head; the German school books had disappeared, and there has been no more German teaching nor preaching.”

If you are wondering if anyone in your family was accused of being a German spy or even someone that did the spying; you are in luck!

Ancestry – available for free when you visit the Indiana State Library – has the following collections: American Protective League Members Record Cards and Registers of Members, 1917-1919 (and yes it includes the state of Indiana!) and American Protective League Correspondence, 1917-1919 – Correspondence on Investigations.

The Indiana State Library also has in its collections the Indianapolis American Protective League Membership List; American Protective League of Indianapolis During World War; call number: [Vault] ISLV 940.3772 I388B.

You can also search the Indiana State Library’s various newspaper databases for ancestors’ names in the results that are returned with the words “German spy” and “American Protective League.”

This blog post is by Angi Porter, Genealogy Division librarian.

Additional Resources

Alien Enemy Index, 1917-1919.

American Protective League. Issues of the Newsletter “Spy Glass,” 06/04/1918–01/25/191. Series A1 16. NAID: 597894. Records of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, 1896–2008, Record Group 65. The National Archives in Washington, D.C.

“Genealogical Records of German Families in Allen County, Indiana 1918;” call number: ISLG 977.201 A425BL.

Genealogical Records of German Families in Allen County, Indiana 1918.

Huntington County in the World War. Volume 1, number 21 – American Protective League.

The Web – “A Revelation of Patriotism.”

“800 ARE NAMED AS ENEMY ALIENS: Complete List Given of Local Residents Affected by Government Order – Names of Unnaturalized Germans Registered Here;” The Indianapolis Star, December 7, 1917, page 12.