The Genealogy Division of the Indiana State Library has digitized early Marion County, Indiana birth returns. Doctors and midwives filled out the returns and sent them to the Marion County Health Department, which would issue a birth certificate. The dates for these returns range from 1882 to 1907. Recording births wasn’t mandatory at the time, so not every birth is included. This makes the returns that are in this collection even more valuable for research.

These cards enrich our understanding of early Indianapolis families. In many cases, the location of both the child’s and parent’s birth, their names, address, age and father’s occupation are listed. Some cards even ask for aspects of the birth itself, such as whether it was easy or difficult, and a reason. These birth returns give us a glimpse into the lives of early Indianapolis residents and even tell the story of the city itself.

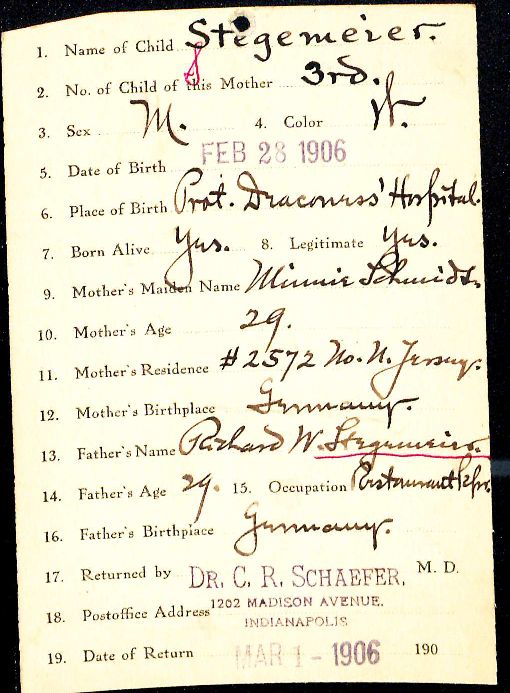

As the holiday season – a time filled with food and festivities – is upon us, it’s the perfect opportunity to feature the birth return for the child of a well-known Indianapolis restaurateur. Restaurant owner, Richard Stegemeier married Minnie Schmidt on Nov. 22, 1900. They had their first child, Richard Jr., on Sep. 10, 1901. Later sons, Karl, whose birth return is pictured here, and Henry, as well as daughters, Alma and Marie, were born into the family. According to the birth return pictured above, Karl was born at the Protestant Deaconess Hospital, which once stood on the spot that is now the parking garage on Ohio Street and Senate Avenue across the street from the Indiana State Library.

As the holiday season – a time filled with food and festivities – is upon us, it’s the perfect opportunity to feature the birth return for the child of a well-known Indianapolis restaurateur. Restaurant owner, Richard Stegemeier married Minnie Schmidt on Nov. 22, 1900. They had their first child, Richard Jr., on Sep. 10, 1901. Later sons, Karl, whose birth return is pictured here, and Henry, as well as daughters, Alma and Marie, were born into the family. According to the birth return pictured above, Karl was born at the Protestant Deaconess Hospital, which once stood on the spot that is now the parking garage on Ohio Street and Senate Avenue across the street from the Indiana State Library.

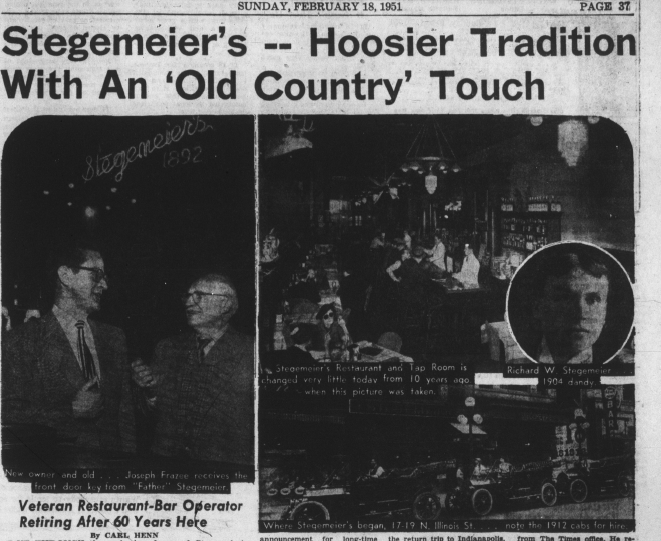

Richard Stegemeier was the proprietor of Stegemeier’s Cafeteria, a beloved institution in Indianapolis. Housed at one time in the basement of the Occidental Building – and other locations, including 17 N. Illinois St. and later 114 N. Pennsylvania St. – Stegemeier’s was known for its hearty German fare, beer and as the meeting place of local movers and shakers. The Illinois St. location was in the basement of the Apollo Theater Building, attracting theater-goers to the restaurant before and after the shows.

The Stegemeier family likely rubbed elbows with various big shots and stars during its years in operation. Famous Indianapolis residents such as Booth Tarkington, James Whitcomb Riley, Dr. Meredith Nicholson, members of the Vonnegut family and more were known to frequent the restaurant. Author, Kurt Vonnegut, Jr., even wrote about a visit to Stegemeier’s in the prologue of his work, “Jailbird.”

Richard Stegemeier immigrated to Indianapolis from Hannover, Germany in 1891 and opened his first restaurant in 1892 with his brother, Henry. Many of those that visited the restaurant remembered it for its substantial meals such as sauerbraten, wiener schnitzel, potato pancakes and bean soup.

On Nov. 25, 1924, an advertisement for the Thanksgiving menu included, “Roast Spring Turkey with Giblet Gravy, Oyster Dressing, Candied Sweet Potatoes and Cranberry Sauce.” Now, over a hundred years later, these items continue to be popular dishes for Thanksgiving dinners around the country.

While most of the food served at Stegemeier’s is still enjoyed today, like chicken and dumplings, beef prime rib, mashed potatoes and apple pie, they also advertised dishes that would make some modern diners’ stomachs churn. Oxtail julienne, boiled ox tongue and calf brains with eggs were all popular enough to be advertised in the April 13, 1911 issue of the Indianapolis Star.

In 1951, Richard Stegemeier retired and sold the business. Over the next few years, the restaurant changed hands three times. It’s likely none of the new owners had the heart for the business that Stegemeier had for his namesake. In 1953, it was reported that the current owner had plans to eventually drop the Stegemeier name. The restaurant was also undergoing major renovations, which involved the removal of the large, ornate bar which was a trademark of Stegemeier’s. A few years later, after the dust had settled from the renovation, Stegemeier’s restaurant closed for good.

After his restaurant days were over, the Sep. 21, 1956 Indianapolis Star caught readers up on Stegemeier’s life in retirement.

“RICHARD STEGEMEIER, retired restaurateur, sat at the counter at Merrill’s, downtown, obviously as much interested in the way food is electronically ordered by the waitresses and conveyed from kitchen to counter as in his noonday snack … Mr. Stegemeier is seen daily about the streets, his mounting years resting lightly on his stalwart shoulders, wearing a cane which he does not need and greeting old friends with booming, resonant voice. It wouldn’t be quite so dreary here in winter if this grand, old man didn’t take off – and by bus too – for Florida to add to the already abundant sunshine down there.”

Richard Stegemeier died in 1961, leaving his mark on Indianapolis through memories of good times, great food and the consequential decisions made at his restaurant by the round table of writers, politicians and leaders who dined there.

This blog post is by Dagny Villegas, Genealogy Division librarian, wishing you the happiest of holidays!

Sources:

“Indiana, Marriages, 1780-1992”, , FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:XF8H-V5V : 13 January 2020), Richard Stegemeier, 1900.

Ancestry.com. U.S., World War II Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947 [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011.

“United States, Census, 1910”, FamilySearch, (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MKPB-HPC?lang=enFri Jul 05 19:47:10 UTC 2024), Entry for Detrick Stegemier and Minnie Stegemier, 1910.

“Stegemeier’s: More than an eating place — an institution.” Indianapolis Star, 09/03/1921, p. 23

“Richard Stegemeier, Restaurateur Dies.” Indianapolis Star, 11/27/1961, p. 25

Henn, Carl. “Stegemeier’s – Hoosier Tradition with ‘Old Country’ Touch.” Indianapolis Times, 02/18/1951, p.37

Dreyer, Gerald. “Stegemeier Bar Removal Means ‘Passing of an Era’.” Indianapolis News, 05/06/1953. P. 39

George, Larry. “Landmark Gives Up.” Indianapolis News 07/29/1955, p. 10