FamilySearch is a free genealogy website that features records from around the world. While the exact records available vary by time period and geographic location, generally speaking, you can access vital records, wills, probates, land records, marriage records, religious records and more. With the addition of Full Text Search, FamilySearch now has a dizzying array of search options that are useful in different contexts. This blog post will help you know which one is right for your research.

Records

On the Records tab, you can search indexes created by FamilySearch indexers over the years. This search includes both full record sets, where you can see the record images, and indexes where the images are not available. This is one of the oldest search features in FamilySearch and it includes many of the core documents for genealogy research, such as federal censuses, marriage records and birth and death records. Only the names in records are indexed, not other text such as business names, addresses or religious terminology.

Full Text Search

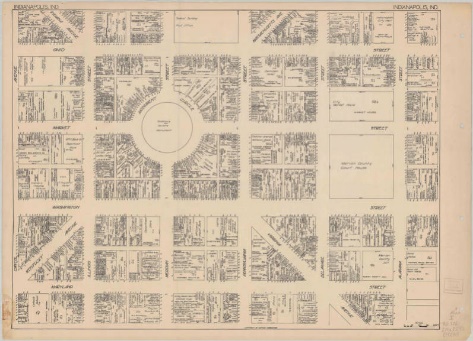

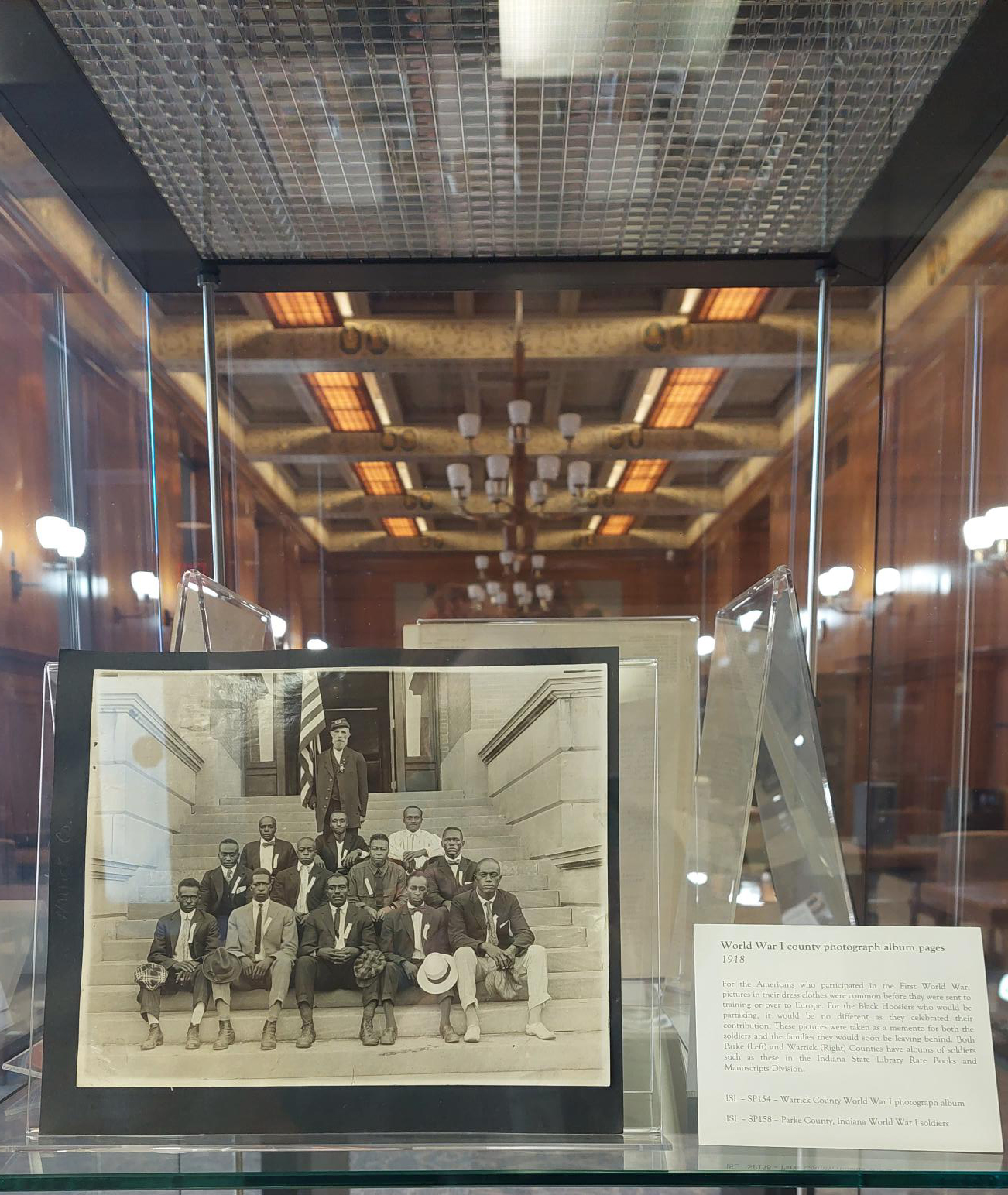

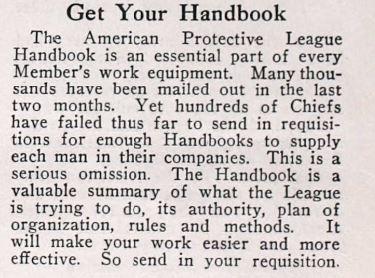

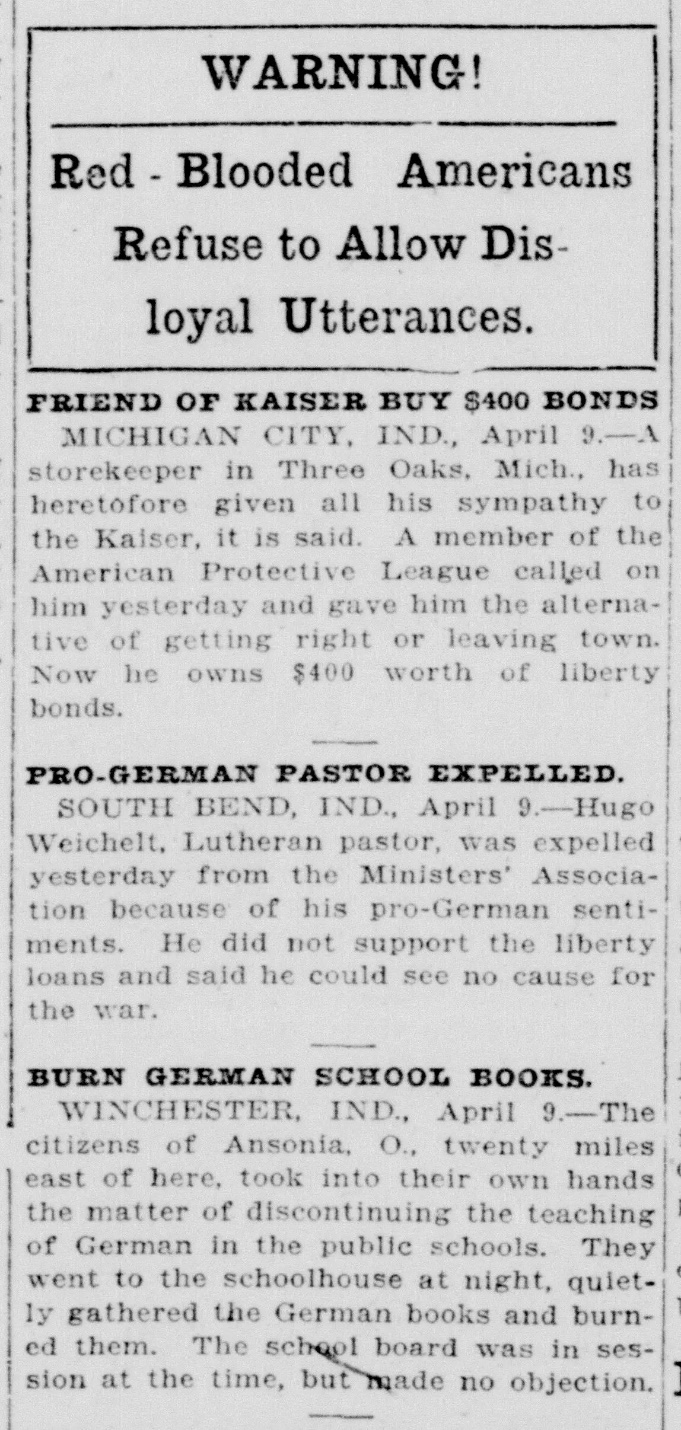

Full Text Search is FamilySearch’s newest search option. It has been available for experimental use for almost a year, but became a full feature in September 2025. Full Text Search uses AI and machine learning to transcribe handwritten documents, much like optical character recognition has been used to transcribe typed documents, such as newspapers. Because this is a new feature, most of the record sets are in English, but FamilySearch plans to add records in other languages as they improve and refine the search features. While some of the records indexed in Full Text Search are also in Records search, most are not. This opens up access to previously difficult record sets, because you can use keyword searching instead of having to browse records page by page. Because the indexing is done by machine, every word is indexed, not just the names of people. So, you can search for anything in the records, such as street addresses, business and organization names and specific legal or technical terminology.

Images

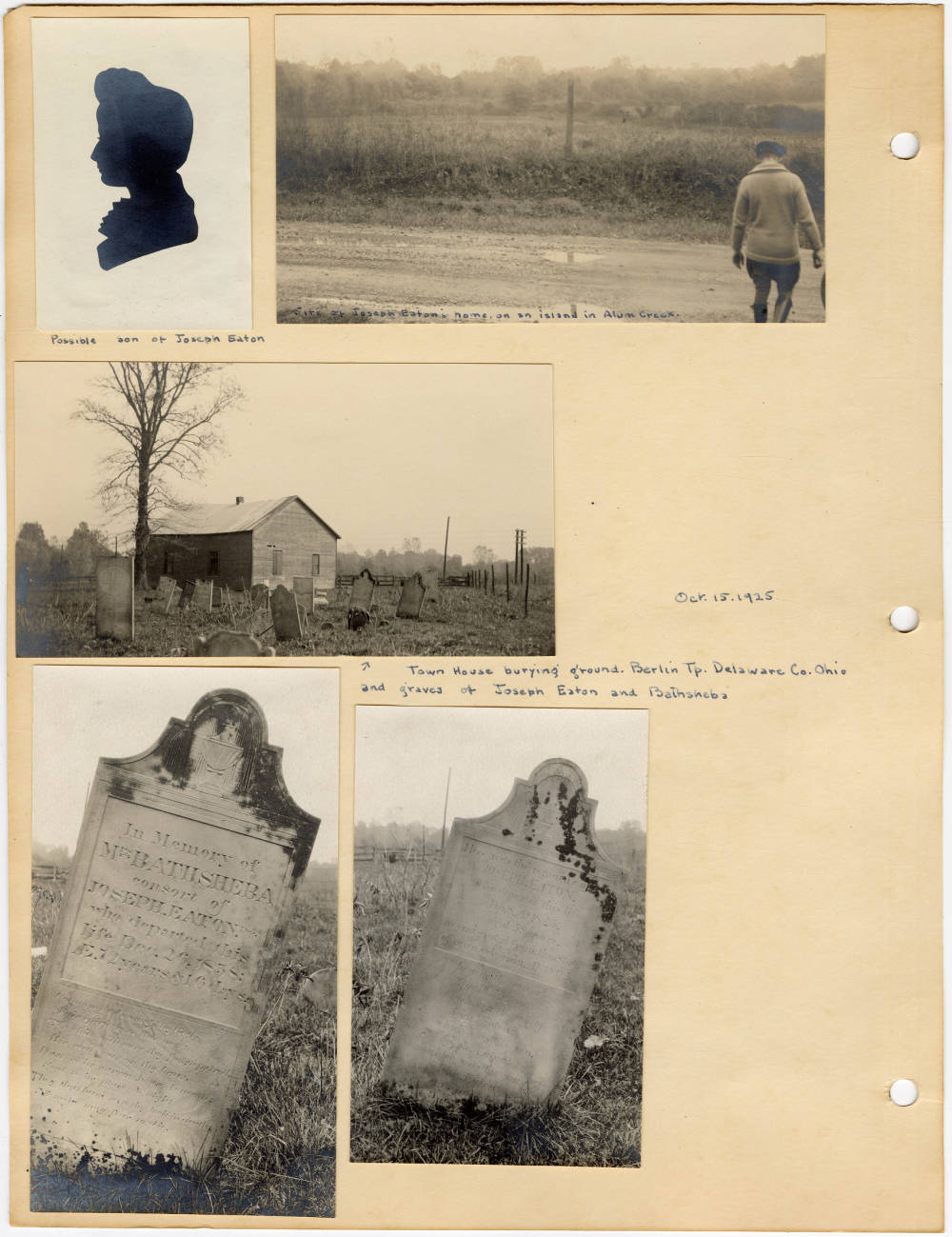

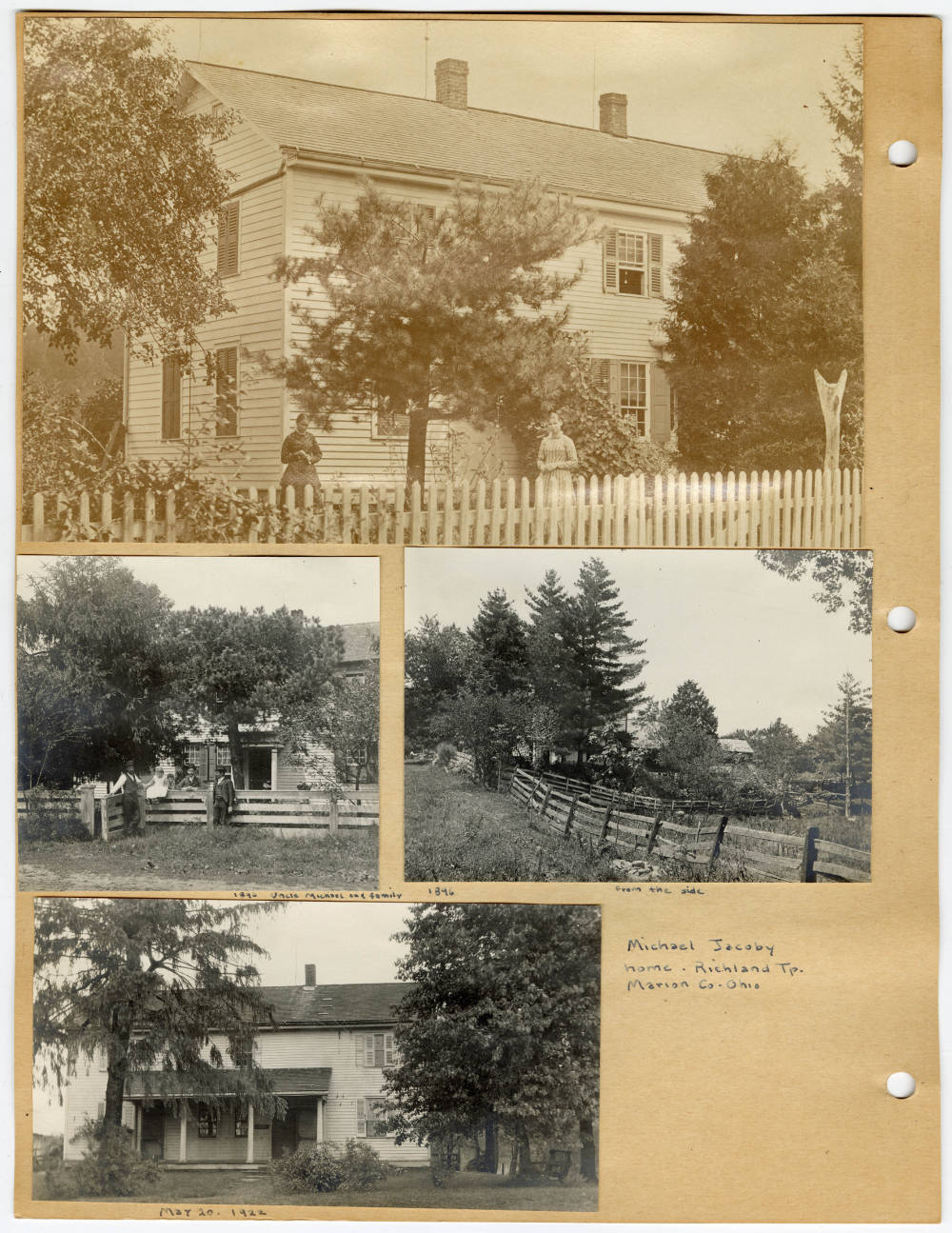

Images is not a true search feature, but it allows you to access unindexed record sets. Although FamilySearch’s volunteer indexers and Full Text Search have made great strides in making records searchable, FamilySearch still has vast swaths of records that are not searchable. Since you can’t search Images for people by name, you have to browse the image sets by geographic location to see what is available for the place you are researching. After choosing a location, you can narrow your results by record type and date range.

Family Tree

One of FamilySearch’s unique features is a shared family tree where users can connect their research with other people’s work. You can also search the tree to see what other researchers have found on the people you are researching. Since this is a shared tree, it’s always good to confirm the accuracy of the research that is presented, but this is a useful way to avoid duplicating efforts in your research.

Genealogies

The Genealogies search lets you search personal family trees and oral genealogies and histories that individuals have chosen to share with FamilySearch. Unlike the Family Tree, other users can’t edit these genealogies. But they are another way of sharing information and research with others.

Catalog

Catalog search works similarly to Images. It allows you to browse FamilySearch’s holdings by geographic location. While Images mostly contains recently digitized record sets, Catalog contains the older materials that FamilySearch microfilmed between the 1930s and the 2010s. Although the film has been digitized and is accessible to researchers, it often has not been indexed so you will need to look page by page through the records to find what you are looking for.

Books

FamilySearch has digitized a large number of books and periodicals from the FamilySearch Library in Salt Lake City as well as from genealogy libraries around the world. These books are fully searchable and you can also download PDF copies to your device. While some books are not available outside of the FamilySearch Library, most can be accessed at home, making research even more convenient.

Accessing FamilySearch

FamilySearch is free to use and accessible from anywhere. However, some record sets are available only at Family History Centers and FamilySearch Affiliate Libraries. Fortunately, the Indiana State Library is a FamilySearch Affiliate Library and you can access everything FamilySearch has to offer through any of our public computers.

This blog post is by Jamie Dunn, Genealogy Division supervisor.