Publishing a book is normally a very lengthy and complex process. Texts must be read thoroughly, proofread, checked for accuracy and edited accordingly. Printing machinery must be calibrated and prepped with enough ink and paper. In the pre-internet era, instant publication of important information in print form faced many hurdles.

The Government Printing Office has always been accustomed to confronting this dilemma. Founded in 1861 as the official publisher of all federal government materials, the GPO has a considerable amount of experience in quickly churning out print materials for consumption by the American public. However, in June of 1954 they faced a particularly difficult challenge. The physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer was undergoing a hearing in front of the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission. At the heart of the hearings was whether Oppenheimer, the man who was selected by the U.S. military to helm the top-secret laboratory at Los Alamos where the atomic bomb was developed, should continue to hold a high-level security clearance and have access to the country’s most sensitive data on atomic weapons. Oppenheimer’s war record, post-war activities and the events leading to his hearing with the AEC in 1954 have been discussed in greater detail elsewhere. In summation, the hearing involved testimony from several dozen witnesses, many of whom were prominent men in political, military and scientific fields. This was not a public hearing and all witnesses were assured by the AEC that their statements would remain confidential.

Logo of the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission.

The chief instigator of the hearings was the chair of the AEC, Lewis Strauss. For a variety of political and personal reasons, Strauss had developed an intense dislike of Oppenheimer and displayed an obsessive fixation on removing him from a position of decision-making power. Concerned that Oppenheimer enjoyed too much public goodwill due to his part in developing the first atomic bombs and helping end the war, Strauss desperately wanted to portray Oppenheimer in as negative a light as possible. The result of the hearing was a foregone conclusion: Oppenheimer’s security clearance was going to be revoked regardless of any testimony for or against it and Strauss felt that making the hearing public would help show the American people that Oppenheimer was not the “atomic age” hero they all believed him to be.

Op-ed from the June 8, 1954 issue of The Indianapolis Star in support of Oppenheimer. From the article: “Dr. Oppenheimer is one of America’s most brilliant scientists. His country owes him a tremendous debt for his work on perfecting the atomic bomb, and later the hydrogen bomb. Certainly America owes him the greatest possible consideration for his services. Certainly we must bend over backward, even to the point of taking some risk, to uphold him now.” This is an example of the kind of sentiment Strauss was desperate to quash with the release of the transcripts.

Sometime shortly after June 11, 1954, Strauss strongly urged, and was able to convince, other members of the AEC to publish the transcripts of the hearings in their entirety and to do it as soon as possible. The AEC desperately tried to reach each witness and alert them that statements they had made under the assurance of confidentially would shortly become public knowledge and fodder for the press.

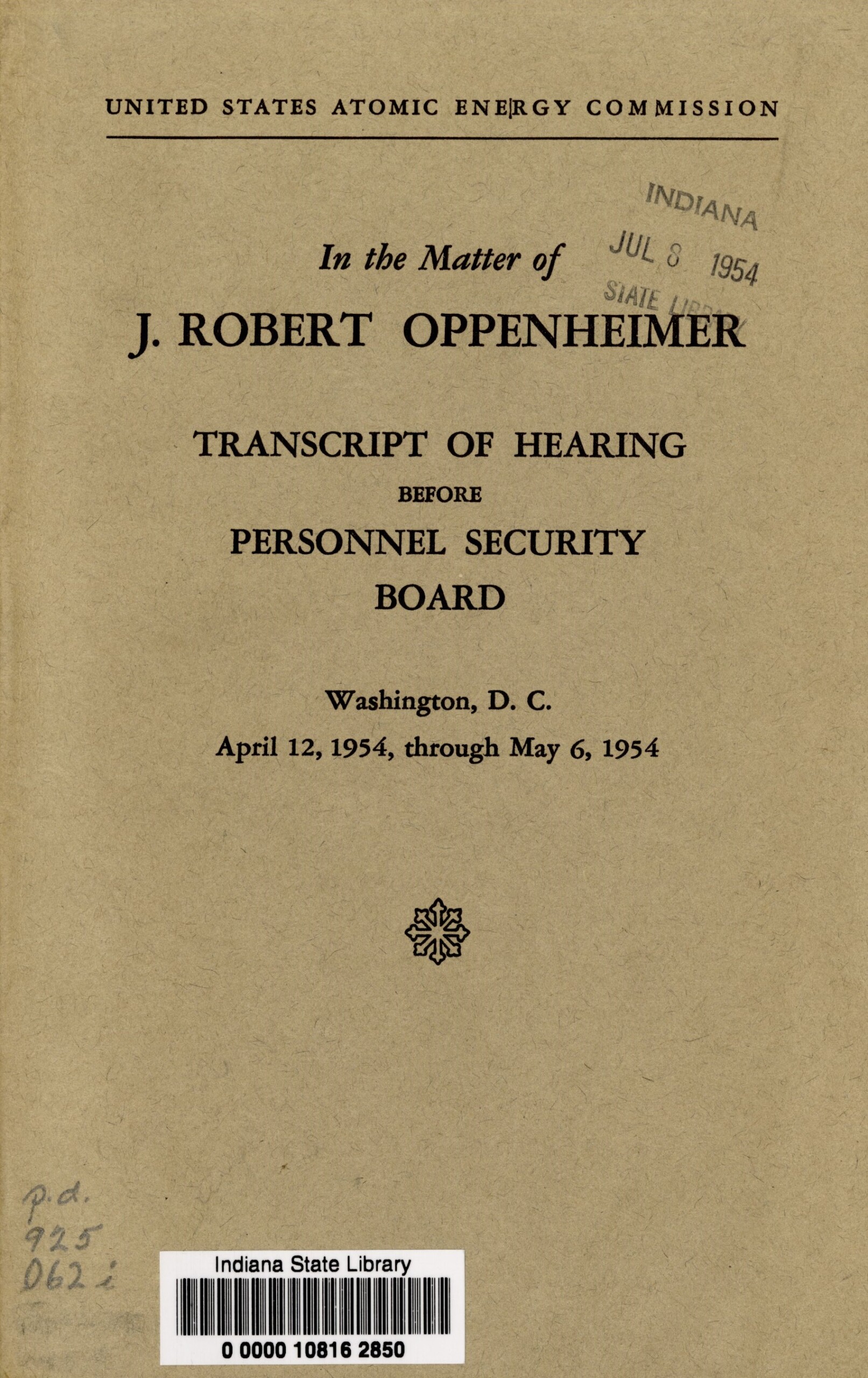

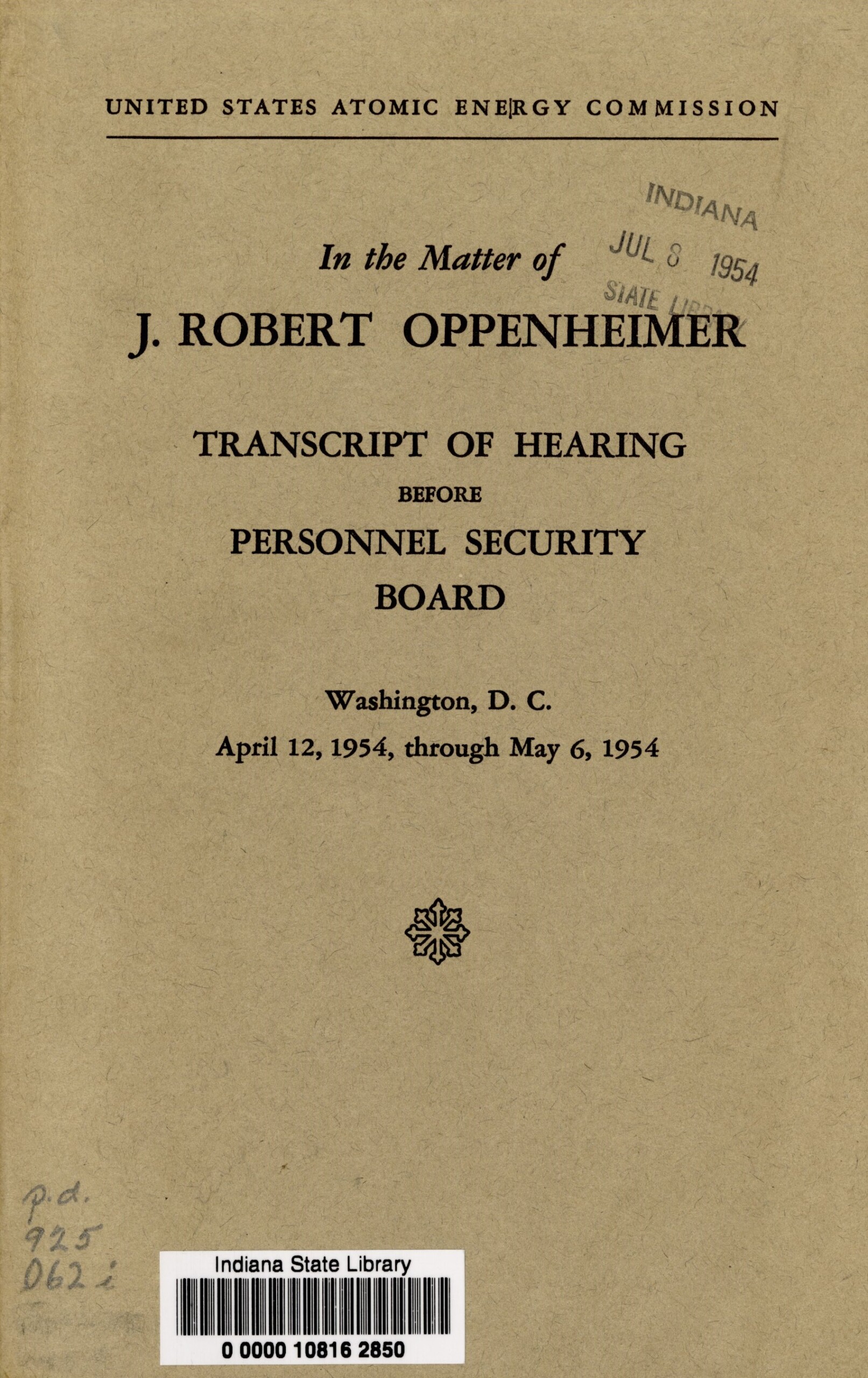

The transcript of the hearing ended up comprising a whopping 3,000 pages. Much of the discussions held within revolved around confidential national security issues and therefore someone would need to read through everything very carefully and redact any information deemed too sensitive for public consumption. Someone else would need to go through the entire transcript and perform basic editing. The final product, titled “In the matter of J. Robert Oppenheimer,” ended up comprising 993 pages and was officially released on June 15, 1954, mere days after Strauss convinced the AEC to go ahead with publication. It was no small feat that the GPO was able to produce this massive volume so quickly and thus make important information available to the American public.

The final product from GPO. Note the date stamped in the upper corner. The volume was released June 15, 1954. The Indiana State Library received their copy several weeks later on July 8, 1954.

The release received a front page headline in the Indianapolis Star.

Ultimately, the swift publication of the hearing did not have the affect Strauss wanted. Instead of damning Oppenheimer in the mind of the American public, many were alarmed at what they perceived as governmental bullying since parts of the hearing veered into salacious aspects of Oppenheimer’s personal life. Others noted that most of the security-related objections to Oppenheimer were well-known prior to his war work on the Manhattan Project. Essentially, the government had known most of the information released in the hearing and still trusted him to oversee the largest top-secret military project in history. The motivation to remove him from playing any role in the further development of atomic weapons was deemed political and petty and would eventually factor into Strauss’s own political downfall several years later.

The full unredacted transcript of the hearing was declassified in 2014 and is available in its entirety from the U.S. Department of Energy here.

In 2022, the decision to revoke Oppenheimer’s security clearance was officially vacated. The full text of the decision made by the Department of Energy is available here.

Sources

Curtis, Charles P. “The Oppenheimer case: the trial of a security system.” New York: Simone and Schuster, 1955. (ISLM QC16.O62 C8)

Schlesinger Jr., Arthur M. “The Oppenheimer case.” The Atlantic, October 1954.

Stern, Philip M. “The Oppenheimer case: security on trial.” New York : Harper & Row, 1969. (ISLM QC16.O82 S69)

U.S. Atomic Energy Commission. “In the matter of J. Robert Oppenheimer: transcript of hearing before the Personnel Security Board.” Washington, D.C. Government Printing Office, 1954. (ISLM p.d. 925 O62i)

This blog post was written by Jocelyn Lewis, Catalog Division supervisor, Indiana State Library. For more information, contact the Indiana State Library at 317-232-3678 or “Ask-A-Librarian.”

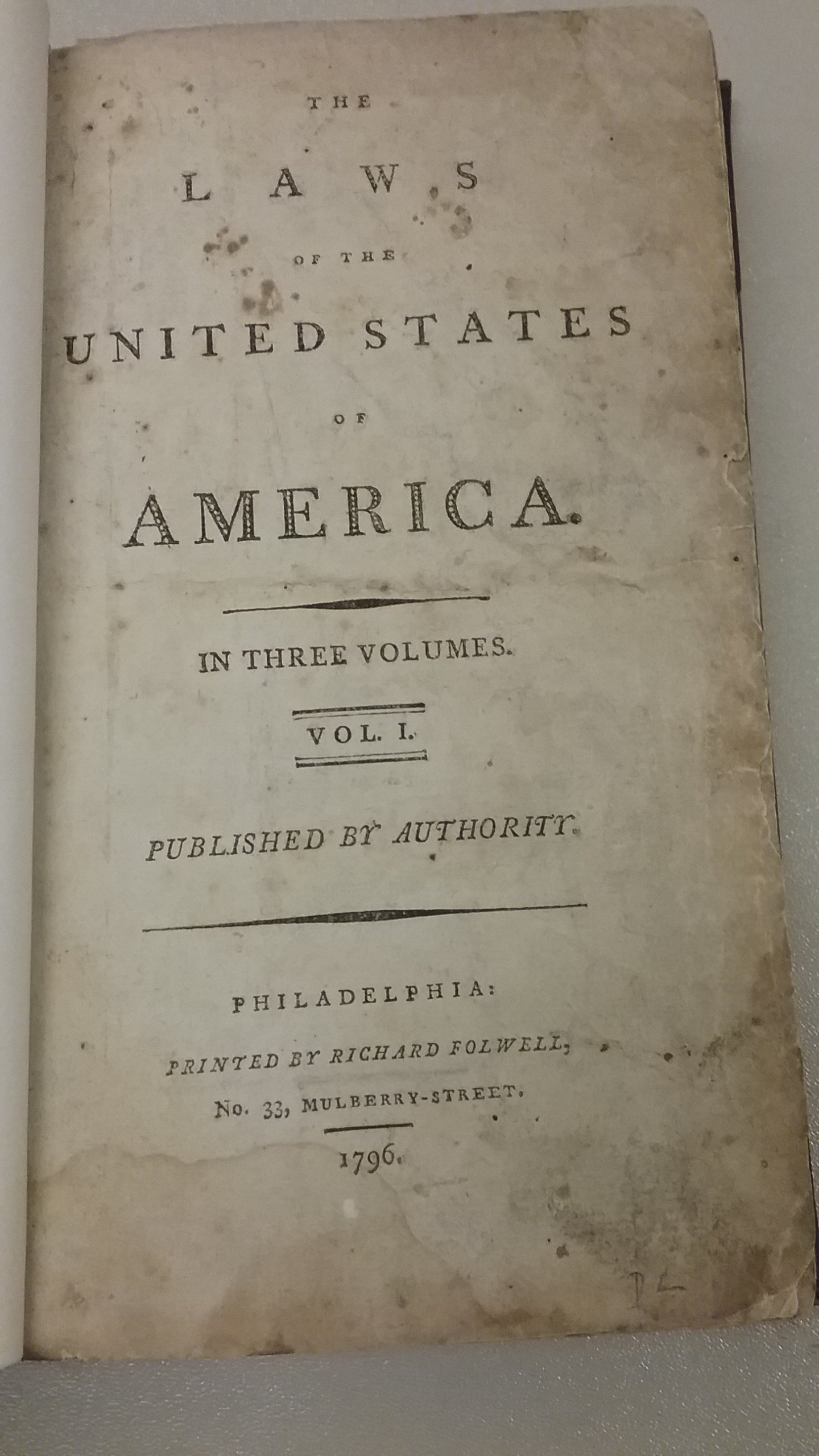

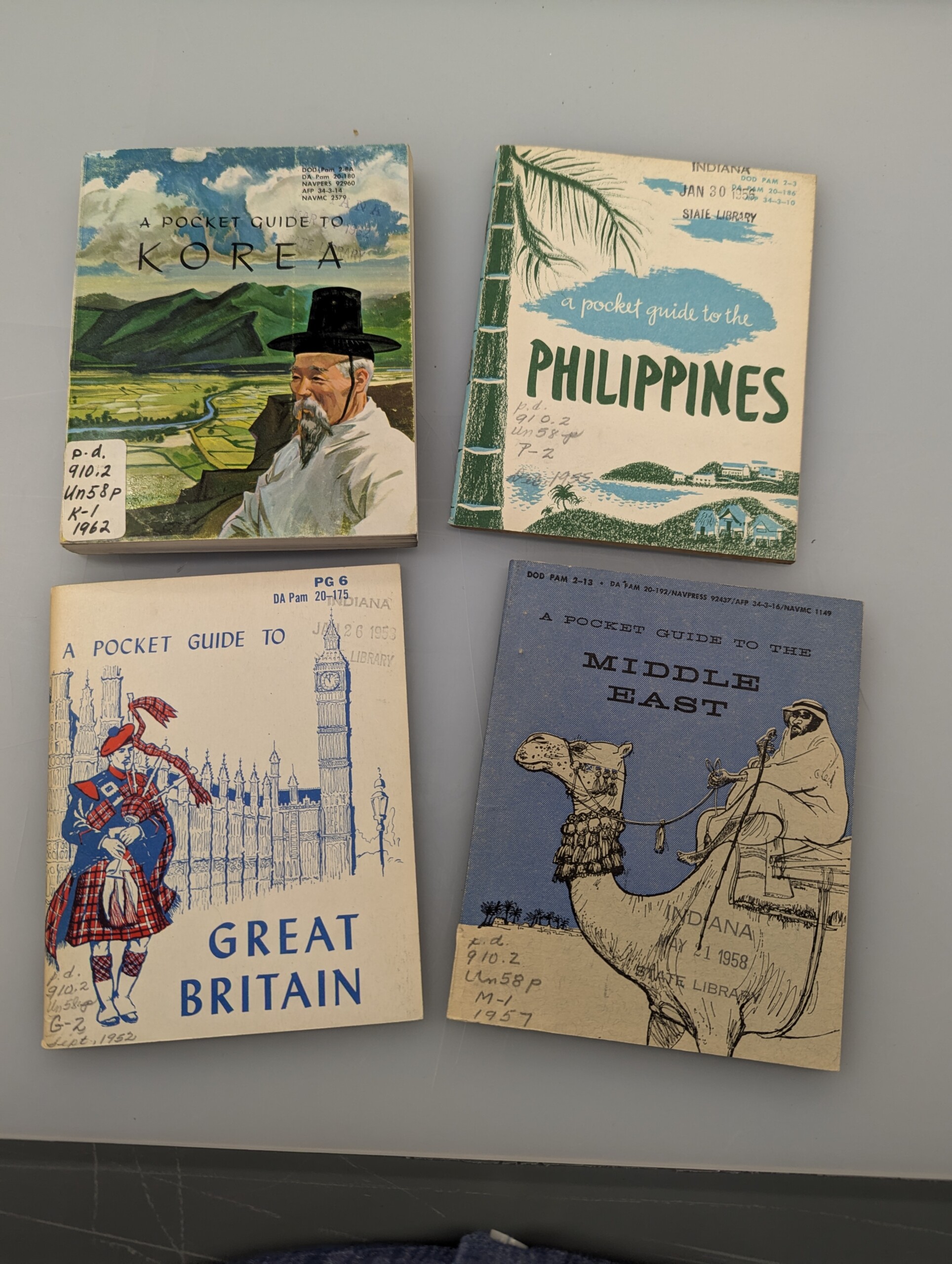

Papers relating to trade with foreign countries, treaties and diplomacy can be found side-by-side on the metal shelves along with state department-issued pocket travel guides.

Papers relating to trade with foreign countries, treaties and diplomacy can be found side-by-side on the metal shelves along with state department-issued pocket travel guides. At first glance, so unwieldy a collection may discourage the Hoosier enthusiast, but if one is willing to burrow (imagine the ground hog), there are discoveries aplenty. Congressional hearings, bland in appearance and recorded on thin white paper, capture the thousands of voices of those called before congress.

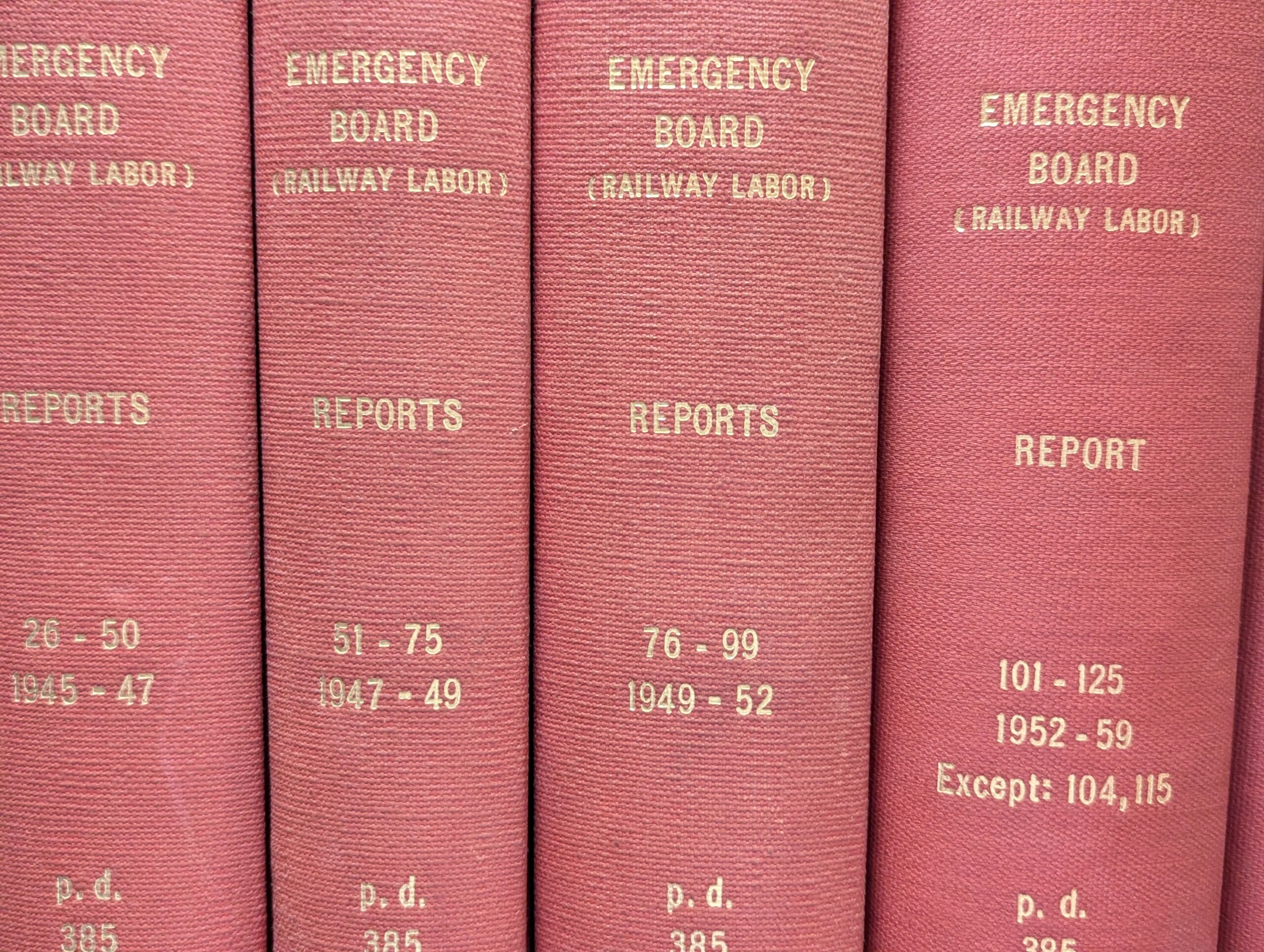

At first glance, so unwieldy a collection may discourage the Hoosier enthusiast, but if one is willing to burrow (imagine the ground hog), there are discoveries aplenty. Congressional hearings, bland in appearance and recorded on thin white paper, capture the thousands of voices of those called before congress. The Coast and Lighthouse Reports record buoys and stations on domestic bodies of water, including Lake Michigan. Soil surveys contain thoughtful county essays on farming, equipment, architecture, labor, and, well, soil conditions. Cattle, sheep and horse diseases are well chronicled, as are the travails of the railroad industry in the United States, from the metal used to lay tracks to the working conditions of the men who did it.

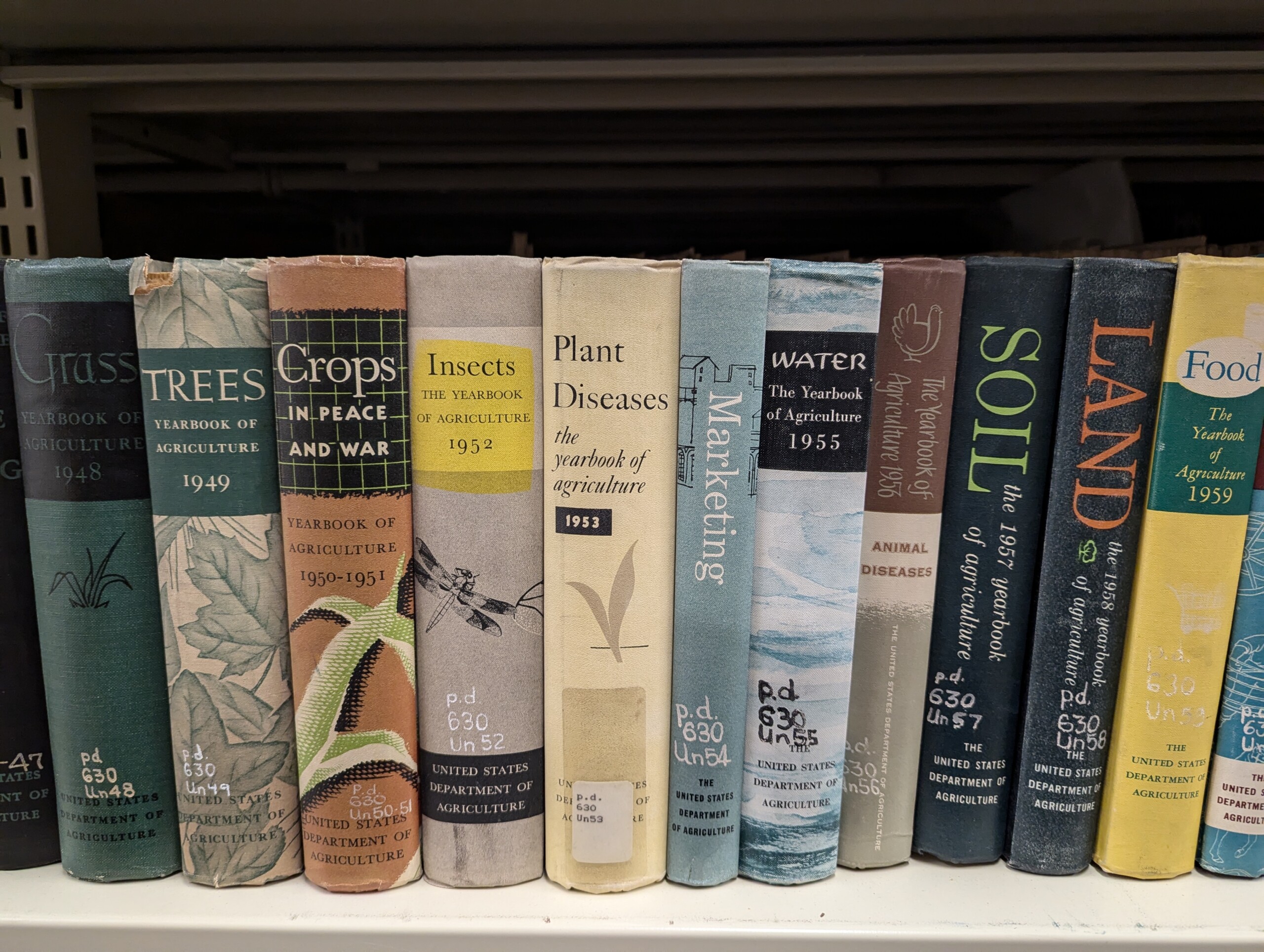

The Coast and Lighthouse Reports record buoys and stations on domestic bodies of water, including Lake Michigan. Soil surveys contain thoughtful county essays on farming, equipment, architecture, labor, and, well, soil conditions. Cattle, sheep and horse diseases are well chronicled, as are the travails of the railroad industry in the United States, from the metal used to lay tracks to the working conditions of the men who did it. Is the family lore correct? Did Indiana experience one of its hottest summers in 1947? Climatological summaries of the state provide the answer, as do yearbooks compiled by the Department of Agriculture.

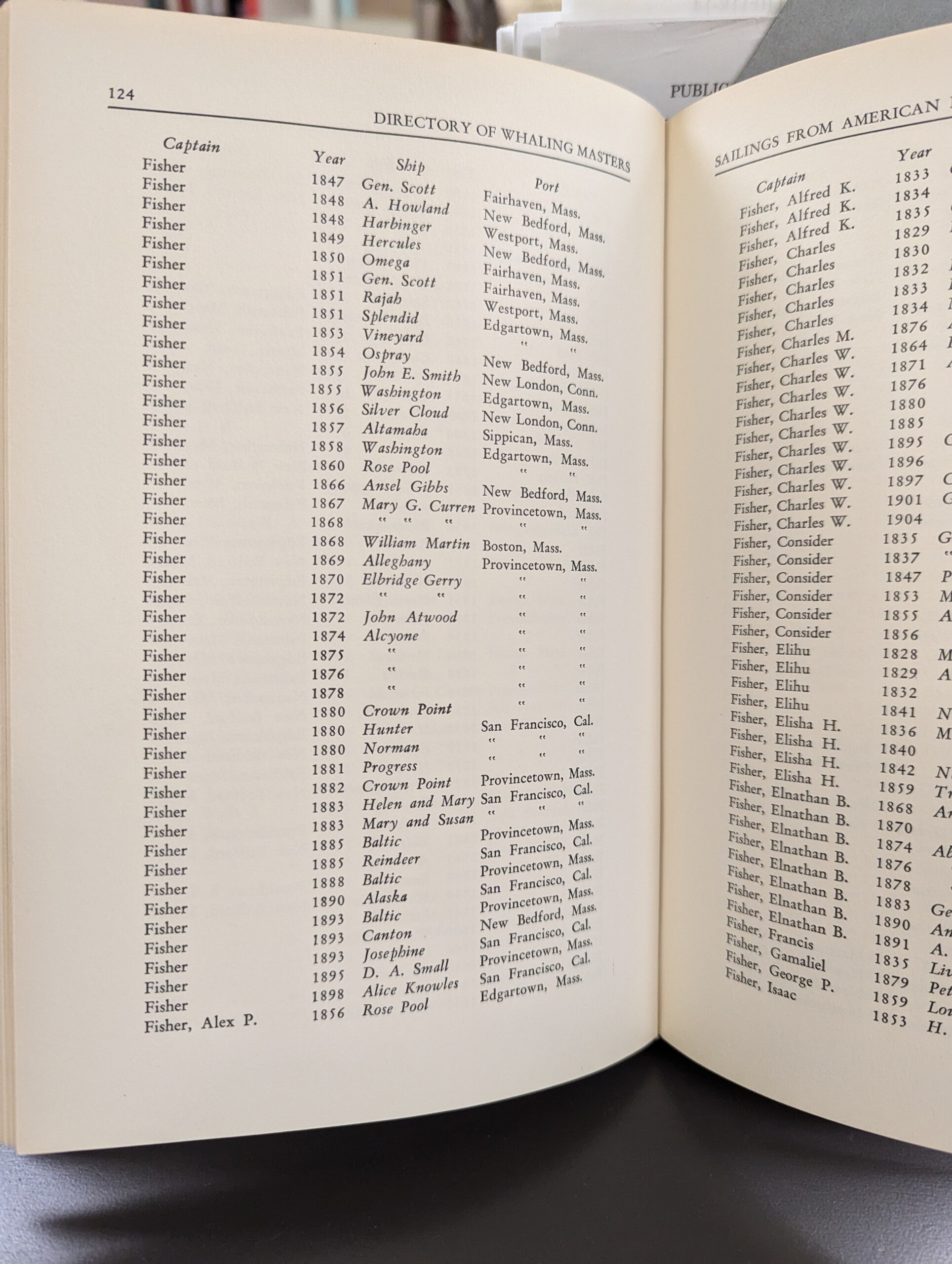

Is the family lore correct? Did Indiana experience one of its hottest summers in 1947? Climatological summaries of the state provide the answer, as do yearbooks compiled by the Department of Agriculture. Maybe Grandpa Fisher really did thread the Rajah through the choppy waters of Westport, Massachusetts, in 1851, hands clasped behind back, headed to the southern seas in pursuit of whales. Find out by consulting “Whaling Masters Voyages, 1731-1925,” which lists ships, captains and ports.

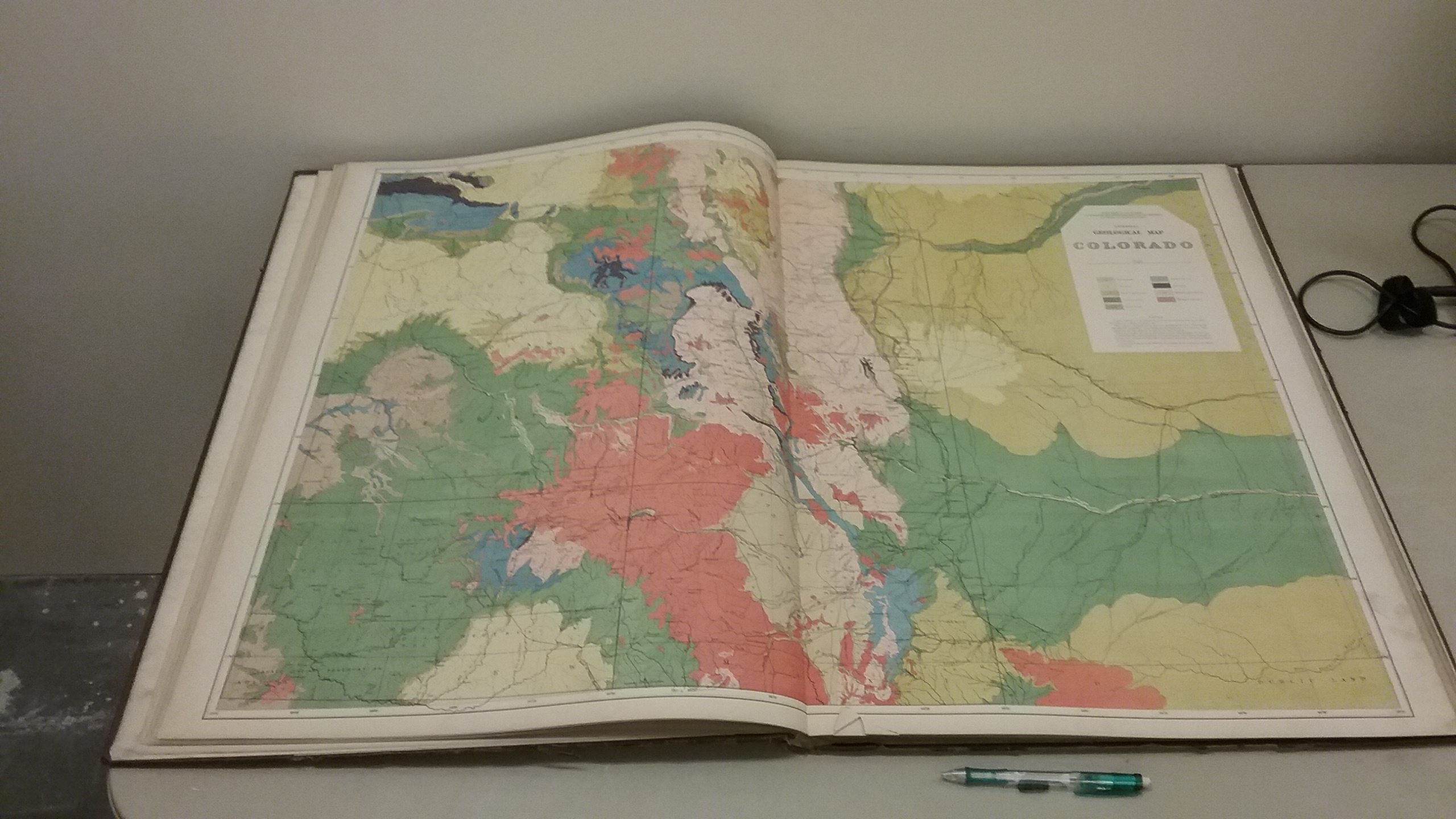

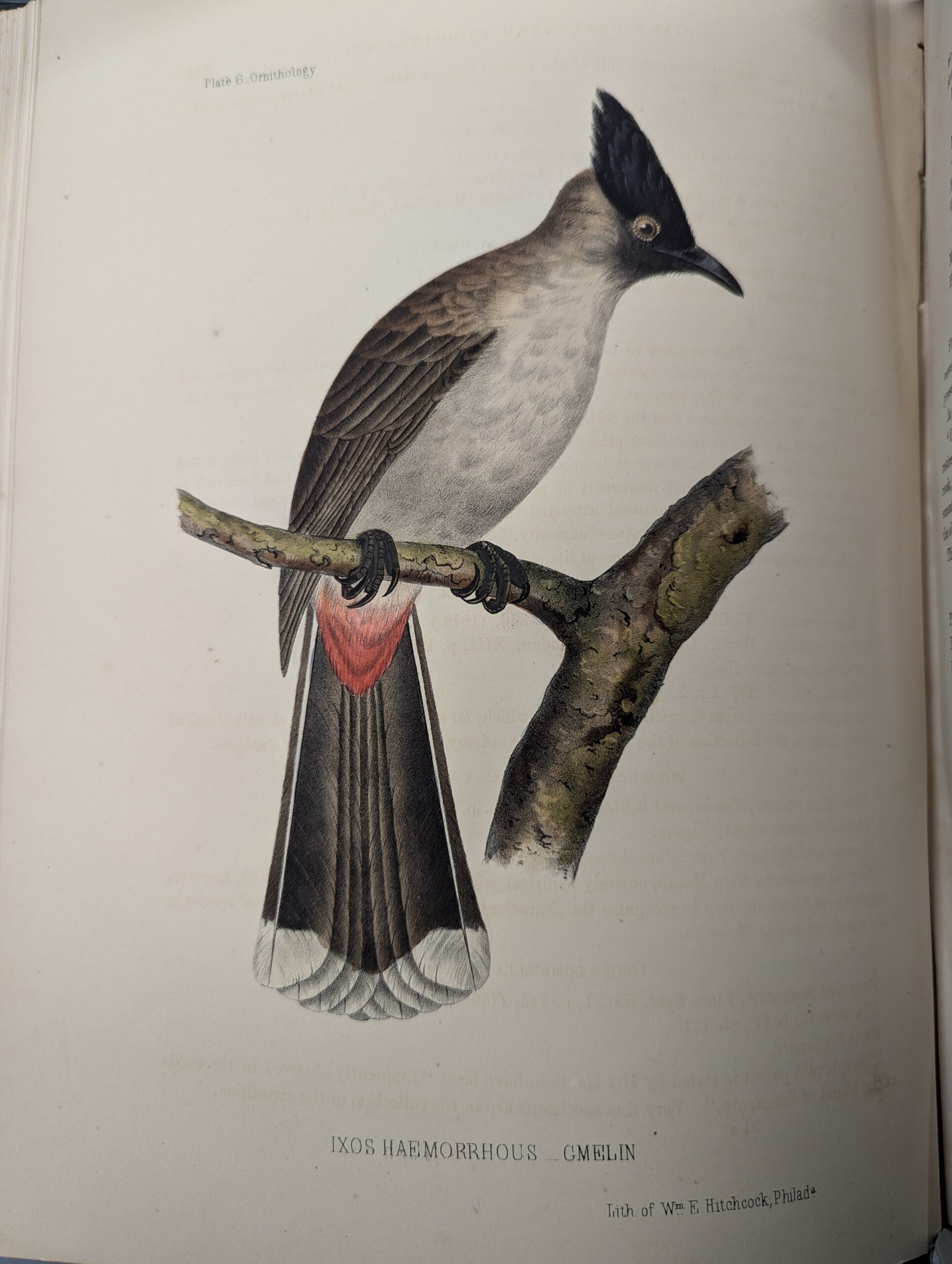

Maybe Grandpa Fisher really did thread the Rajah through the choppy waters of Westport, Massachusetts, in 1851, hands clasped behind back, headed to the southern seas in pursuit of whales. Find out by consulting “Whaling Masters Voyages, 1731-1925,” which lists ships, captains and ports. Home to hundreds of thousands of documents, reports, papers, plates, graphs and census material, no mere introduction can do the P.D. Room justice.

Home to hundreds of thousands of documents, reports, papers, plates, graphs and census material, no mere introduction can do the P.D. Room justice.