For much of its early existence, Shelby County maintained a very small population of African American citizens. Prior to the Civil War, their number was less than 100. The 1851 Indiana Constitution prohibited the settlement of “Negro or Mulatto” people in the state which caused the African American population of Indiana to stagnate for over a decade. However, with the conclusion of the Civil War and the removal of the 1851 restriction, Blacks began to migrate into the state. By the early 1900s, Shelbyville was home to over 600 African Americans.

Picture of students in front of an unidentified schoolhouse from the late 1800s. From the Indiana Picture Collection, Rare Books and Manuscript Collection.

The Indiana General Assembly mandated that separate schools be set up for Black communities in Indiana and the first such school for Shelbyville was created in 1869. By the early 1900s, this school was renamed Booker T. Washington School No. 2 and was located at the corner of Howard and Harrison streets where it served the community for several decades until it became so dilapidated it was officially condemned by the State Board of Health in 1914.

Photo of the Booker T. Washington School. From “Getting open: the unknown story of Bill Garrett and the integration of college basketball” by Tom Graham.

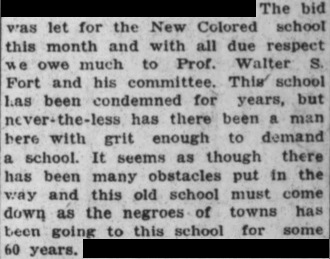

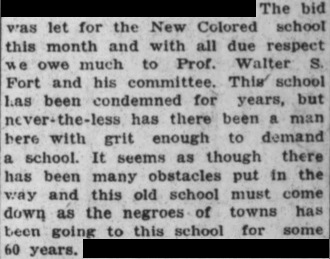

Despite suffering from official condemnation, the school continued to operate as both funds and perhaps the inclination to repair or replace the building were not forthcoming. The situation was so dire that a journalist for the African American newspaper the Indianapolis Recorder declared in 1930, “There is a number of citizens in our city who have stables that are palaces beside this old building.”

Indianapolis Recorder, May 10, 1930. From Hoosier State Chronicles.

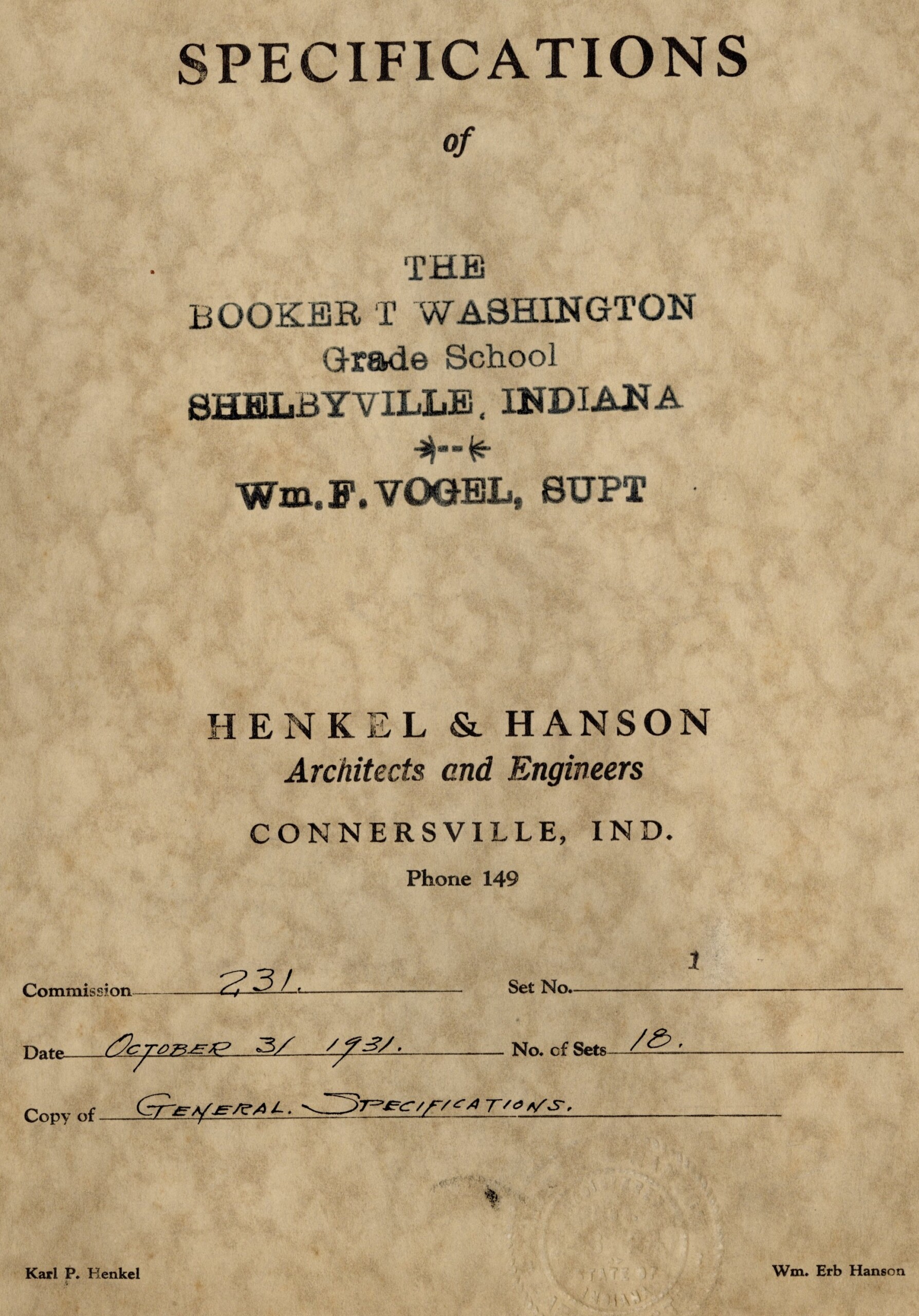

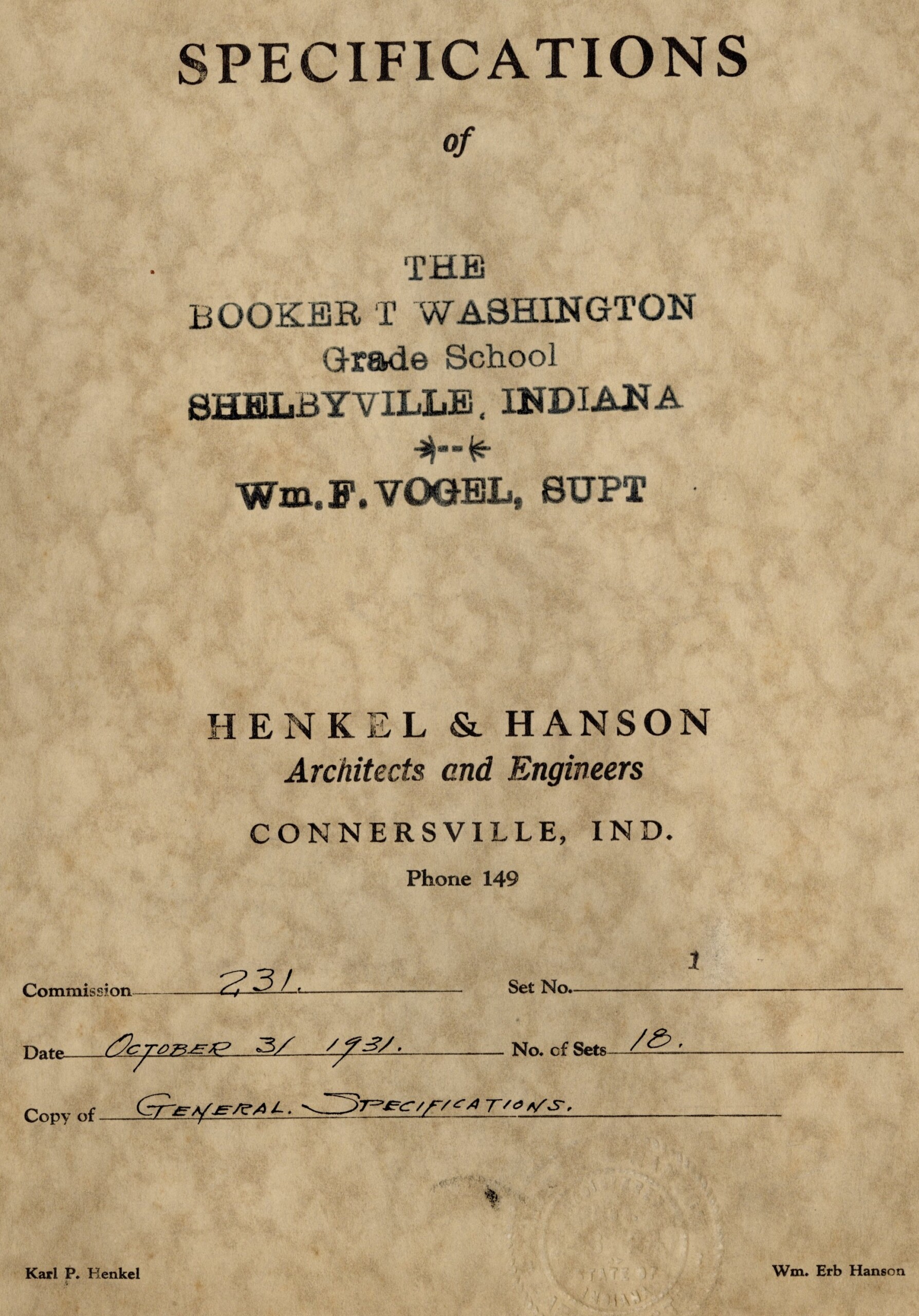

In response to the situation and at the urging of the school’s principal Walter S. Fort – often affectionally called “The Professor” – plans to create an entirely new school building were put in place in October 1931. A copy of the proposed building’s specifications is held in the Rare Books and Manuscripts Collection at the Indiana State Library.

Cover, Booker T. Washington Grade School building collection (S3327), Rare Books and Manuscript Collection.

The specifications for this building were diligently typed up into a 78-page booklet created by the architecture firm of Henkel & Hanson from Connersville, Indiana. This plan maintained the school’s location at the corner of Harrison and Howard streets. The new school building would have a stage, a gymnasium, skylights, stone window sills made of “Indiana Oolitic limestone” and “jade green American method asbestos shingles.” The document describes a utilitarian and modern building that would have been a vast improvement over its predecessor.

Indianapolis Recorder, Dec. 26, 1931. From Hoosier State Chronicles.

While the old school enjoyed an outdoor basketball court behind the building, the inclusion of an actual gymnasium would have delighted students such as Bill Garrett, who attended Booker T. Washington in the 1930s and would later go on to have a successful basketball career first at Shelbyville High School and later at Indiana University where he became one of the first Black basketball players in what would become the Big Ten Conference.

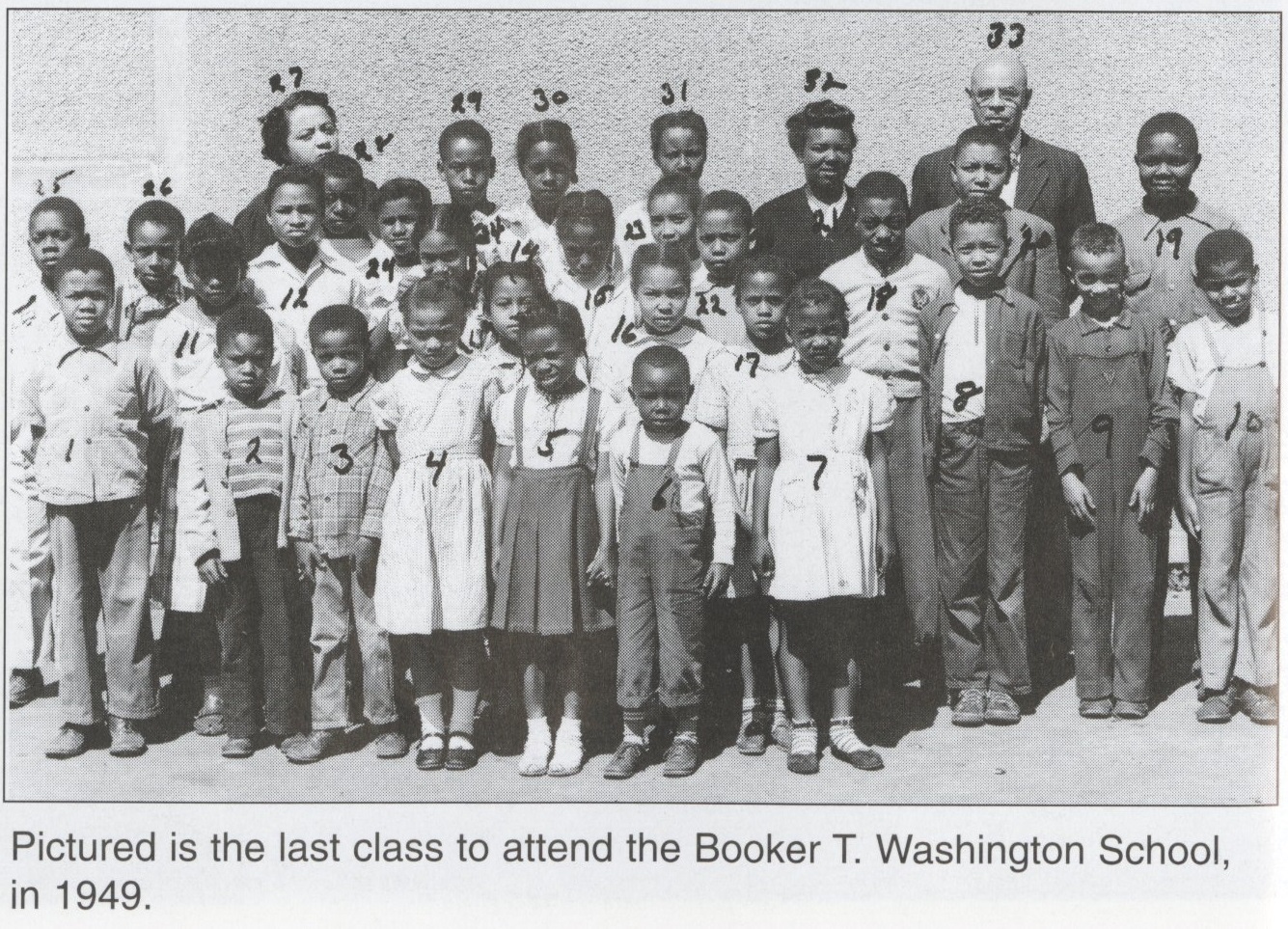

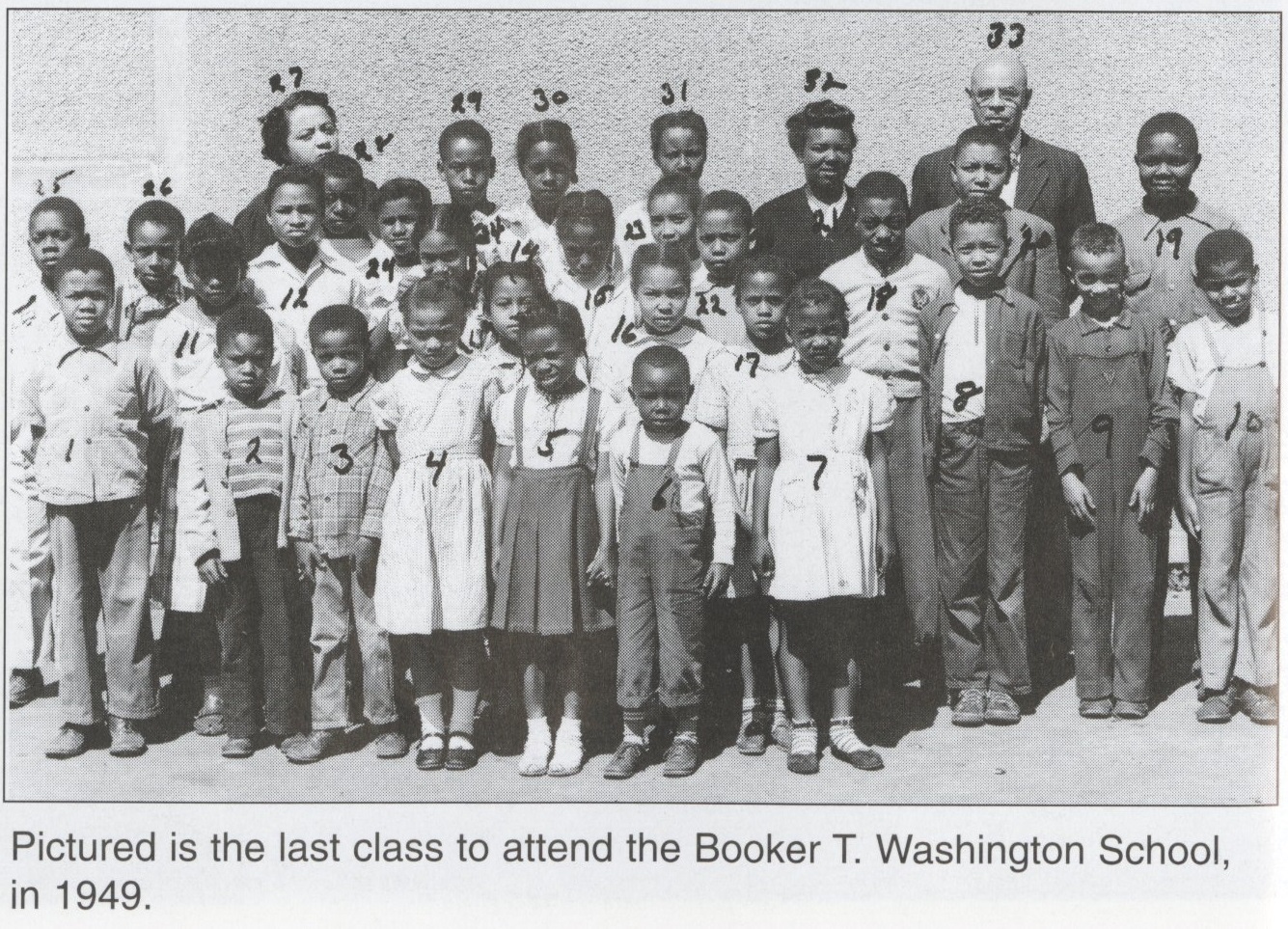

Unfortunately, this building was never actually constructed. No definite reasons can be discerned as to why the project got so far along in the planning process only to be abandoned, but it can be surmised that by 1932 the economic fallout from the worsening Great Depression made utilizing public money on a school intended for African American children a low priority for the city of Shelbyville. It’s also possible that Shelbyville school officials knew that complete school integration was on the horizon. By the end of the 1930s, older students were already integrated into the local high school and Booker T. Washington functioned solely as an elementary school. While the new building was never constructed there is evidence that the City eventually secured money to fix the old one through the Public Works Administration, a federal program intended to both fund building projects and provide employment to thousands of workers during the Great Depression. Instead of building an entirely new building, the PWA money was used to make some basic repairs to the already existing structure. The school remained in operation until it was closed in 1949 when all Shelbyville schools were officially integrated.

The man labeled 33 in the above picture is possibly principal Walter S. Fort, a well-loved and respected advocate for his pupils. He was instrumental in attempts at improving the school building. From “Shelbyville: a pictorial history” by Beverly Oliver.

This blog post was written by Jocelyn Lewis, Catalog Division supervisor, Indiana State Library. For more information, contact the Indiana State Library at 317-232-3678 or “Ask-A-Librarian.”

Sources

Graham, Tom. “Getting open: the unknown story of Bill Garrett and the integration of college basketball.” New York: Atria Books, 2006. (ISLI 927 G239gr)

McFadden, Marian. “Biography of a town: Shelbyville, Indiana, 1822-1962.” Shelbyville: Tippecanoe Press Inc., 1968. (ISLI 977.201 S544sm)

Oliver, Beverly. “Shelbyville: a pictorial history.” St. Louis: G. Bradley Publishing, Inc., 1996. (ISLI 977.201 S544Zso)

Shelby County Historical Society. “Shelby County, Indiana: history & families.” Paducah, Kentucky: Turner Publishing Company, 1992. (ISLI 977.201 S544sc)

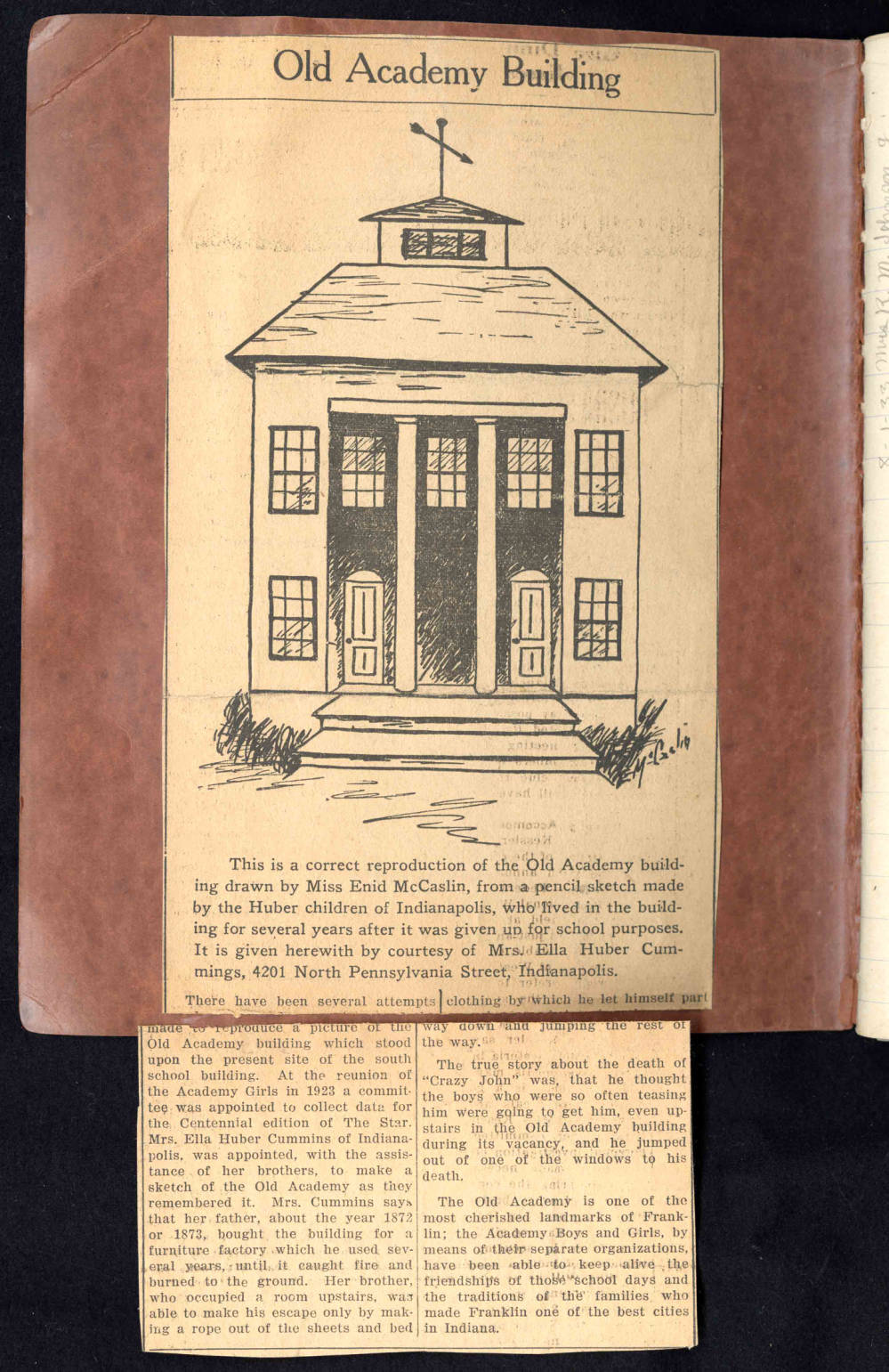

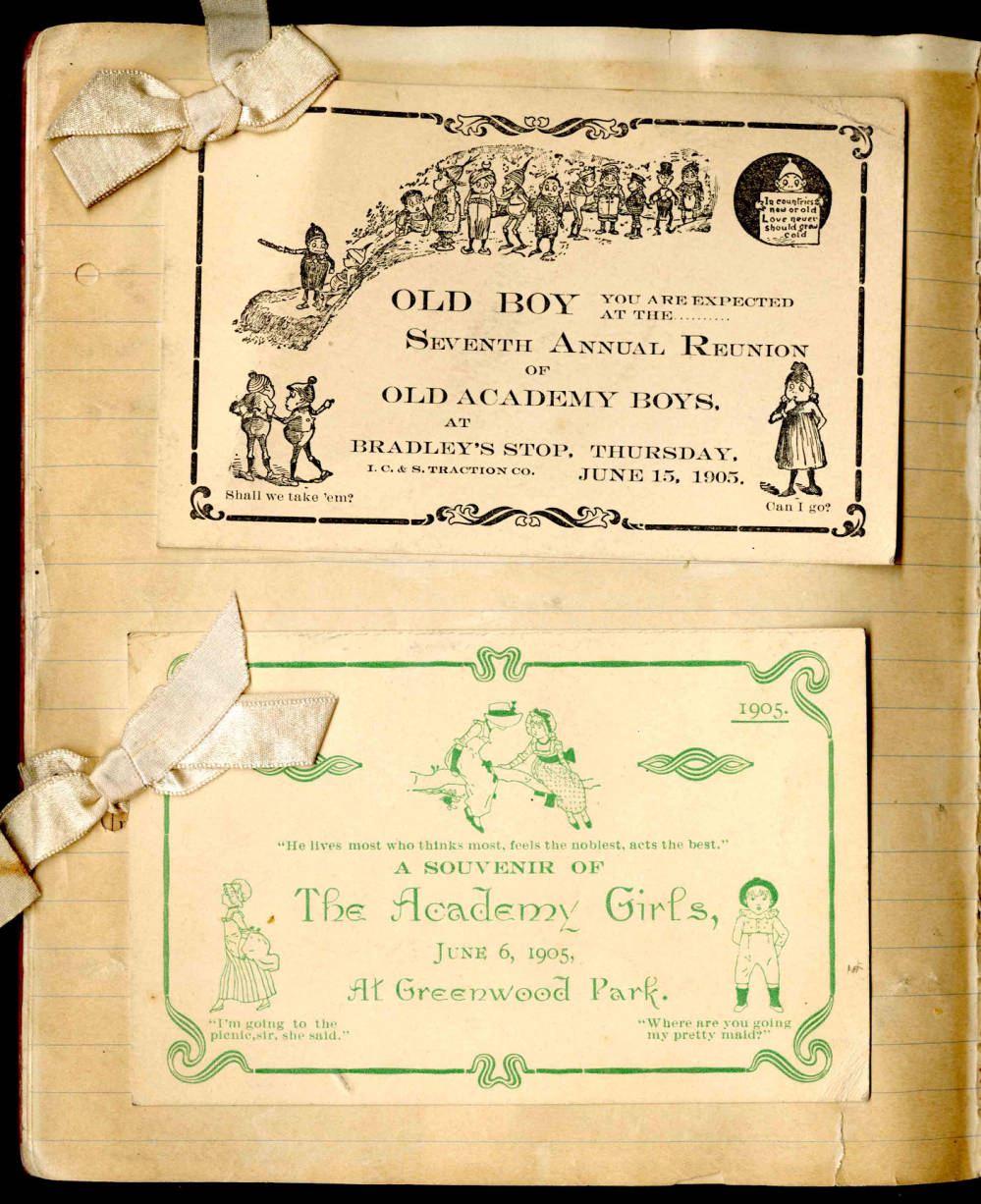

In our Digital Collections at the Indiana State Library, we recently added “USM U.S. Mail Composition Book no. 702,” used as a scrapbook to organize and document the history of The Academy Girls reunions from their first in 1905 up to 1914. You will see on the inside cover a newspaper article with a sketch of The Old Academy followed by general notes from their first meeting. It is here that we learn that their first reunion, “an all day affair” would be held at the Greenwood Park on June 6, 1905. Total attendance would be 36 members, a number that would rise and dwindle over the years following their first reunion.

In our Digital Collections at the Indiana State Library, we recently added “USM U.S. Mail Composition Book no. 702,” used as a scrapbook to organize and document the history of The Academy Girls reunions from their first in 1905 up to 1914. You will see on the inside cover a newspaper article with a sketch of The Old Academy followed by general notes from their first meeting. It is here that we learn that their first reunion, “an all day affair” would be held at the Greenwood Park on June 6, 1905. Total attendance would be 36 members, a number that would rise and dwindle over the years following their first reunion. The Academy Girls continued to meet me many years after, at least until the late 1920s as the group began to shrink. The venues included Garfield Park and the Old Academy grounds on Monroe Street in Franklin. The Franklin Evening Star recounted the history of the Old Academy and their reunions in an article on Nov. 12, 1963.

The Academy Girls continued to meet me many years after, at least until the late 1920s as the group began to shrink. The venues included Garfield Park and the Old Academy grounds on Monroe Street in Franklin. The Franklin Evening Star recounted the history of the Old Academy and their reunions in an article on Nov. 12, 1963.