When searching for church records for ancestors, sometimes figuring out where the records are located can be a challenge. The first step is to know the religion or domination, but, what if the religion or domination is unknown? Luckily, there are a few tricks that can help find answers.

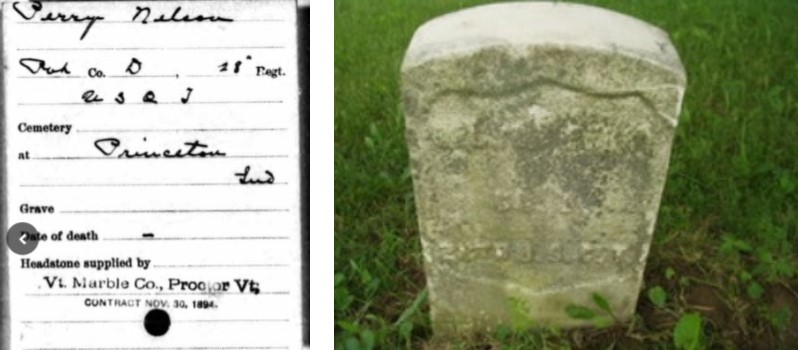

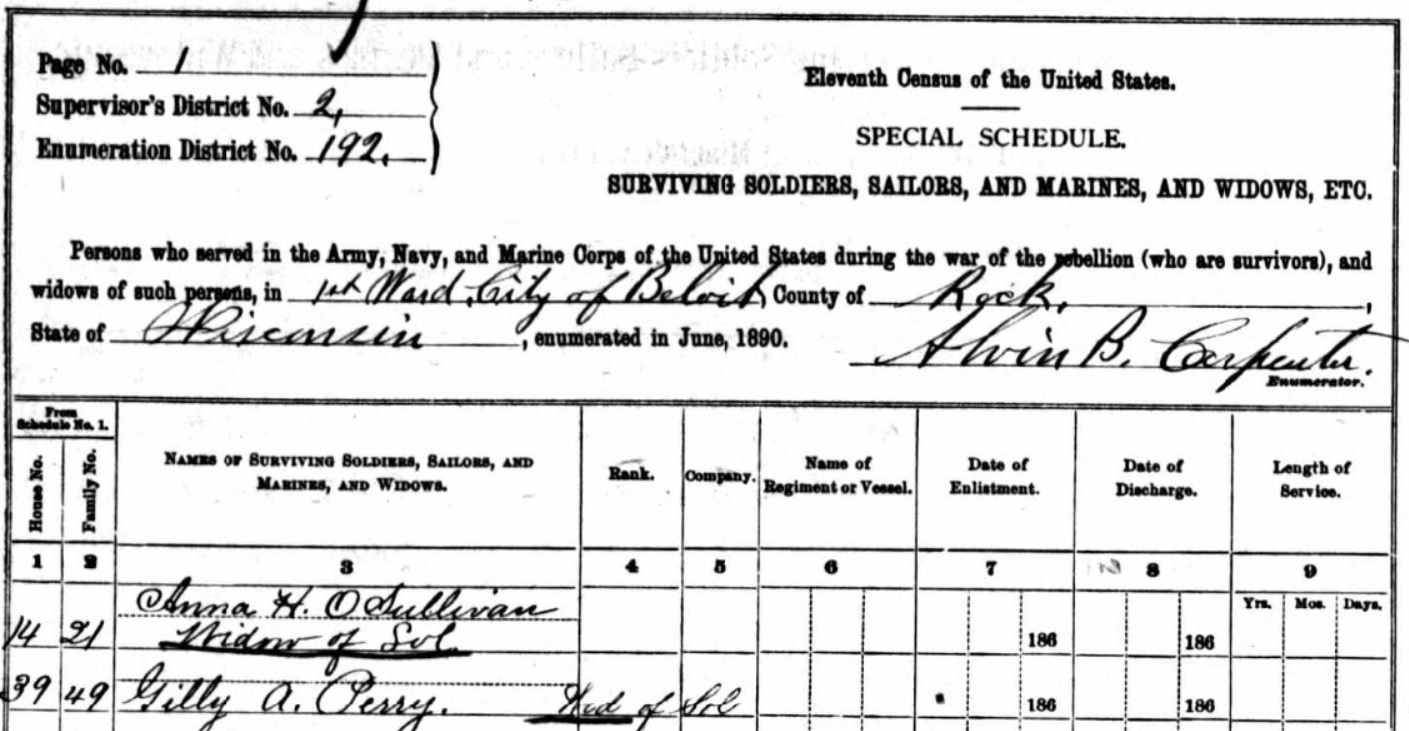

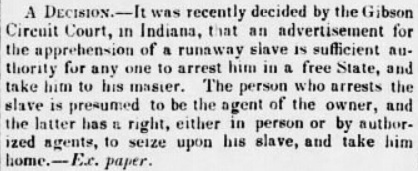

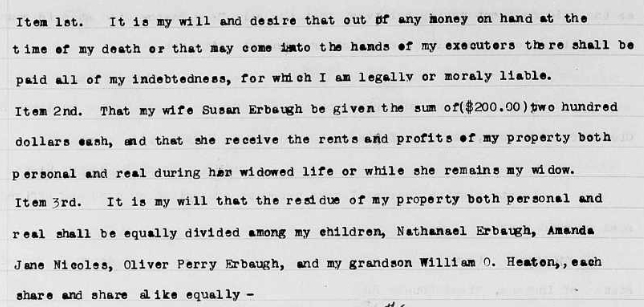

Note the place of burial. Is the cemetery your ancestor is buried in associated with a church? Obituaries can list the church location of funeral services as shown in the example below.

Muncie Evening Press, Muncie, Indiana, Friday, Feb. 6, 1914, page 10.

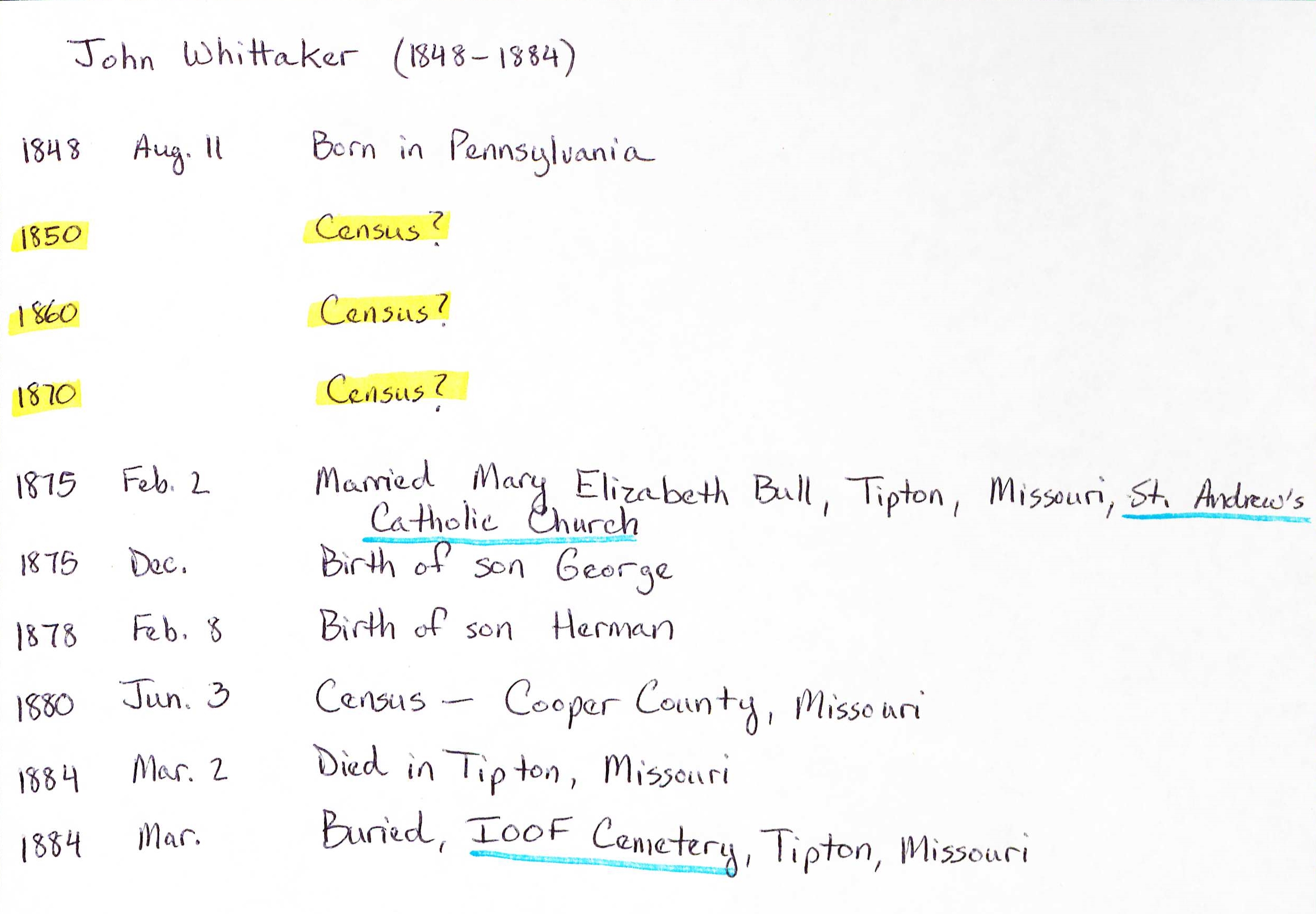

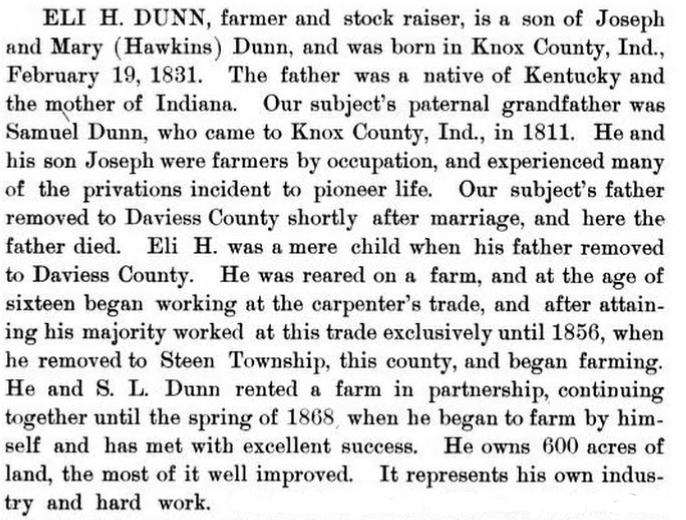

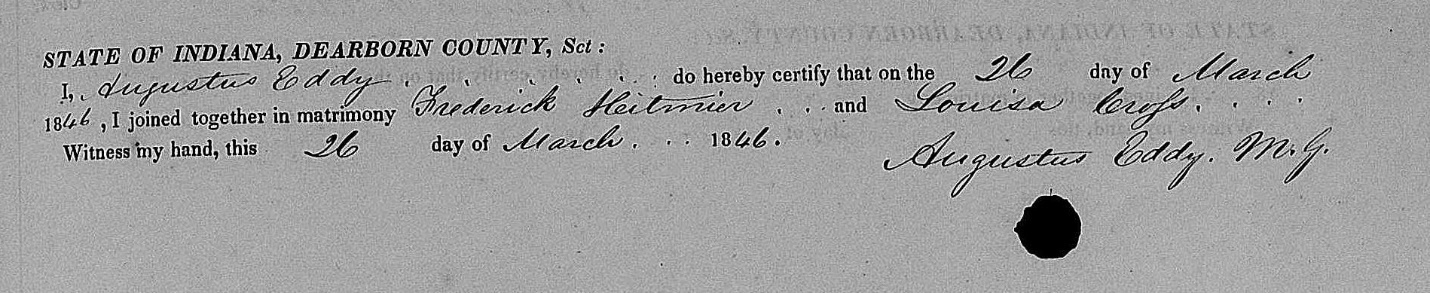

Clues can also be found in marriage records. Look for the name of the officiant performing the marriage ceremony. When examining a marriage for the officiant’s name, it is useful to know the abbreviations that are sometimes used in the in record; M.G. indicates a minister of the gospel, J.P. is for a justice of the peace.

If your ancestors were married by minister of the gospel, research the officiant to see what church he or she is affiliated with. Sources to help find a minister’s affiliation include county histories, city directories and the online List of Pastors and Ministers – with their denomination and years and location of service.

Below is the minister of the gospel’s name: Augustus Eddy. He has signed this marriage record in Dearborn County.

“Indiana Marriages, 1811-2019,” database with images, FamilySearch, Dearborn, 1846-1854, volume 8, image 5 of 652; Indiana Commission on Public Records, Indianapolis.

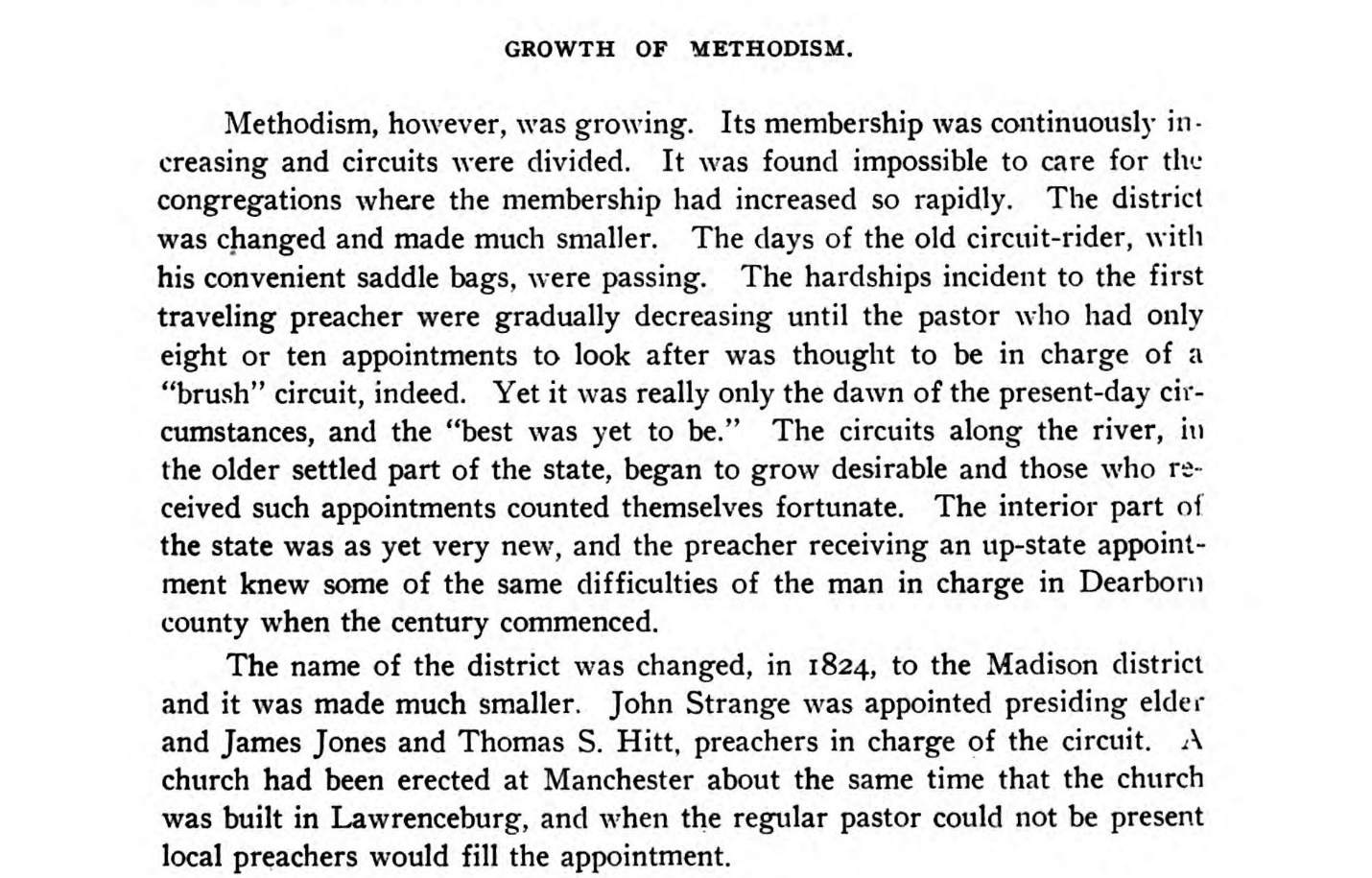

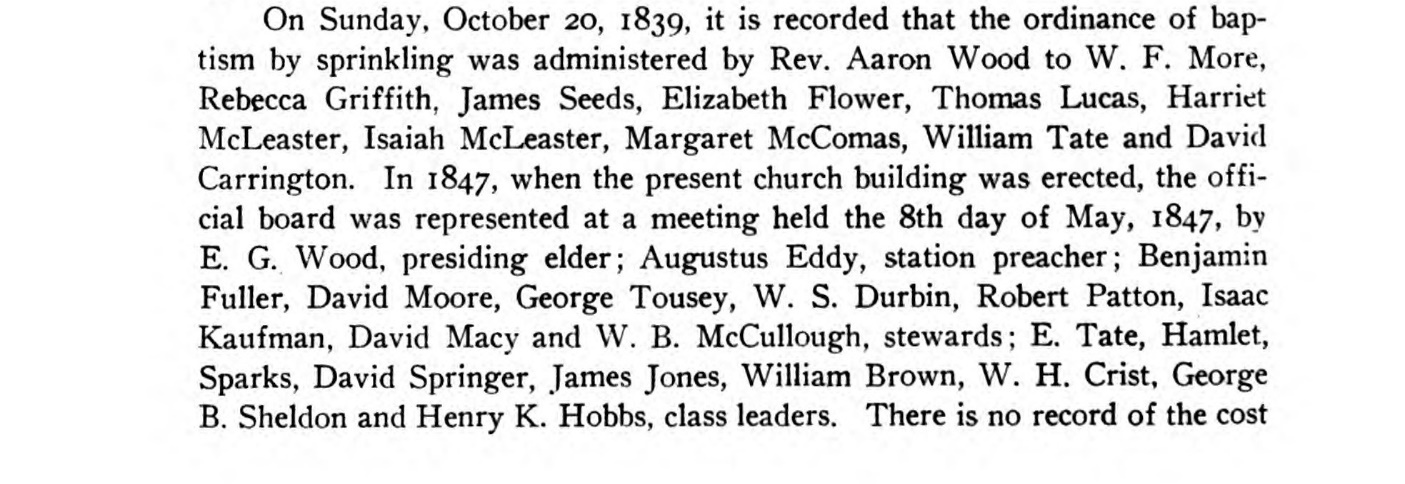

Eddy’s name is noted in the “Growth of Methodism” chapter in a Dearborn County history.

“History of Dearborn County, Indiana: Her People, Industries and Institutions, with Biographical Sketches of Representative Citizens and Genealogical Records of Old Families” by Archibald Shaw, page 387; call number: ISLI 977.201 D285s 1980, Indiana State Library.

“History of Dearborn County, Indiana: Her People, Industries and Institutions, with Biographical Sketches of Representative Citizens and Genealogical Records of Old Families” by Archibald Shaw, page 388; call number: ISLI 977.201 D285s 1980, Indiana State Library.

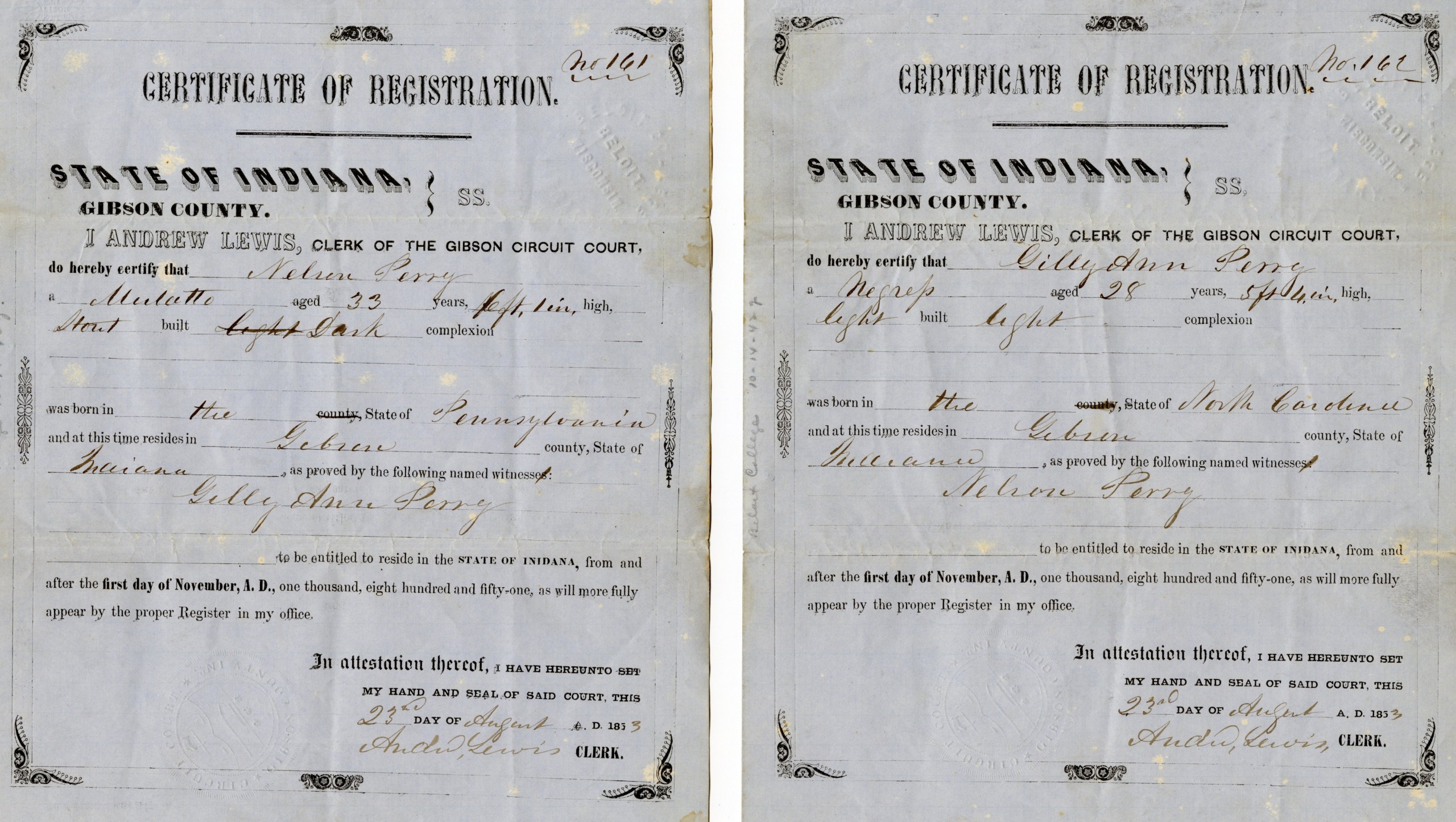

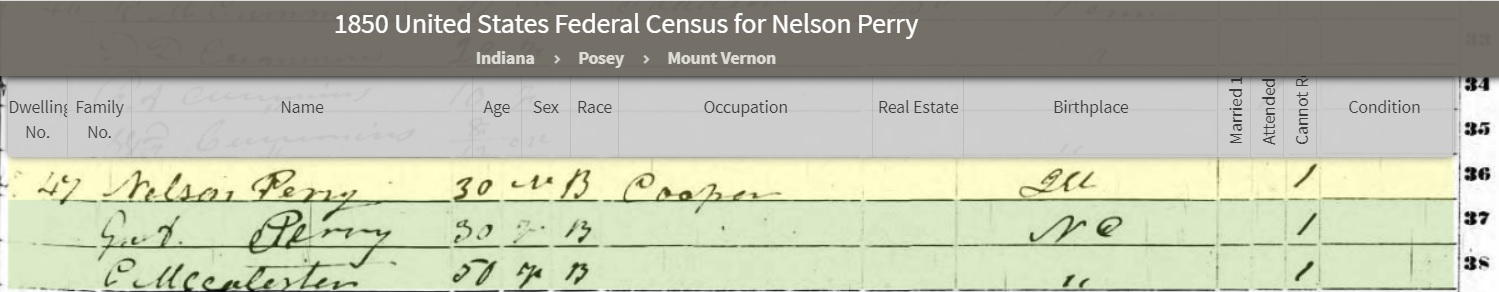

Surprisingly, migration routes can be the path to discovering an ancestor’s religion or domination. An ancestor who moved from Pennsylvania to the Carolinas to the Midwest (e.g., Indiana and Ohio) may mean that the ancestor was a Quaker. The Religious Migration web lesson from Family Search provides additional information on these types of migration patterns.

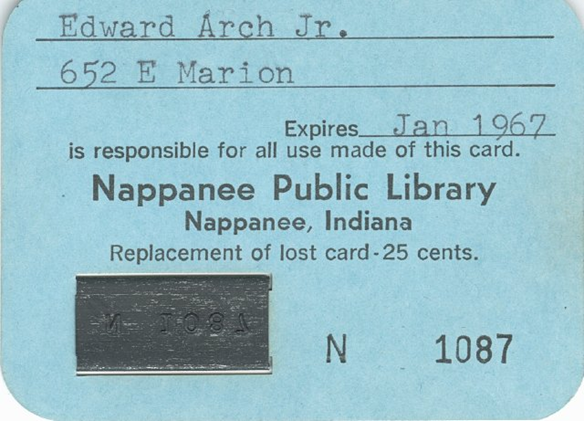

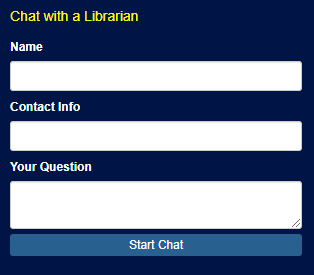

The next step is locating the records. Of course, there are databases such as Ancestry and Family Search.

To find church records in Ancestry; first, select the Search tab, from the Filters list select Directories & Member Lists, next select Church Records and Histories. In the Keyword field add the domination to limit the results. (Don’t forget Ancestry is FREE to use at the Indiana State Library!)

Family Search has some helpful tools for searching Indiana church records through their database. The Indiana Church Records wiki provides tips and links for finding and searching church records in the state of Indiana. Family Search also has a collection of Indiana Quaker (Religious Society of Friends) meeting records.

Stephen P. Morse – famous for his map tools – has provided a list of one-step links for accessing church records through Family Search, the list is organized alphabetically by state.

The next obvious places to find church records are libraries. At the Indiana State Library, you can search the online catalog for Indiana church records. Here is a list of suggested search terms for finding church records in the State Library’s catalog:

- Church records and registers – Indiana

- Catholic church – Indiana

- Lutheran church – Indiana

- Quakers – Indiana

- Society of Friends – Indiana

- Baptists – Indiana

- Indiana Church History

- County name (Ind.) registers

Other tools provided by the Indiana State Library; a bibliography of Selected Church and Religious Genealogical Resources and Resources Listing a Variety of Denominations.

The Indiana State Library Digital Collections can be searched at the library or at home. To search, select advanced search, then enter the search term “church.” Finally, from collection lists checkmark Religion in Indiana.

Indiana State Library manuscripts holdings has a Baptist church history collection. To make an appointment to view the collection please send an email to the State Library.

The Allen County Public Library Genealogy Center has a collection of church records through their free online Fort Wayne and Allen County Resources (scroll down to see the church records).

Other agencies that may have church records are genealogy and historical societies. The Monroe County History Center’s library has a Church Index for the years 1818-1900, the index is searchable by surname or church name. A resource available from The Indiana State Historical Society is a series of articles about Hoosier Baptists.

Sometimes church records can be found in universities or colleges archive collections, particularly if a university or college was founded by religious group. For example, many Hoosiers have Kentucky ancestors. The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary Archives has the History of Gilead Baptist Church, Hardin County, Kentucky, 1824-1924 and biographical data re Elder Warren Cash of Virginia and Kentucky, 1760-1849 – view a copy of it online.

The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary also happens to have a collection of Indiana Church Histories, 1834-1991. An in-person visit is necessary to view these records.

Here are some examples of where to find church records by the type of church:

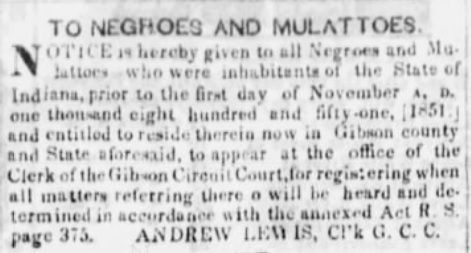

African American churches

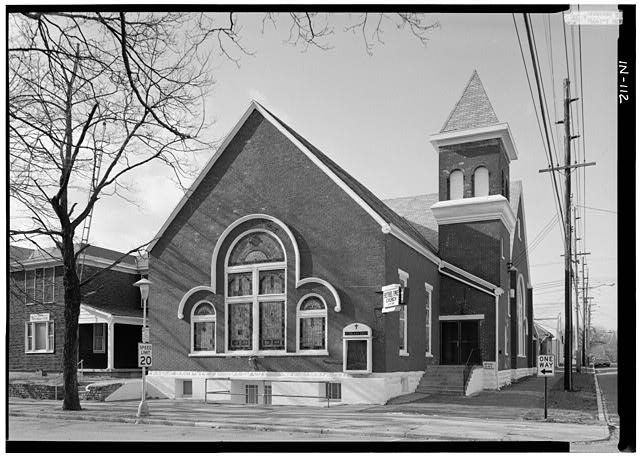

Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church, 200 Sixth Street, Richmond, Wayne County, IN. Photo: Library of Congress.

A fine repository for information about African American churches in the South is The Church in the Southern Black Community. Some of the oldest African American churches established in Indiana were African Methodist Episcopal churches, and the Indiana Historical Society provides the (Indianapolis) Bethel A.M.E. Church Collection.

If searching Family Search for African American church records, try searching: “African American church records name of state.”

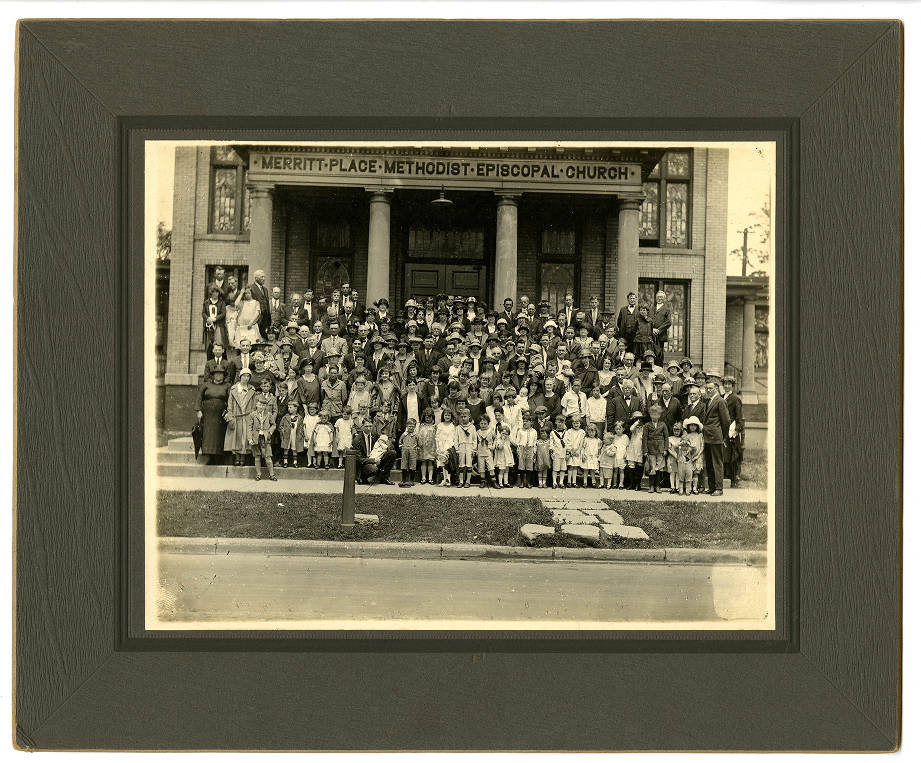

Methodist

The United Methodist church provides a guide for searching ancestors that belonged to the United Methodist church. If searching for ancestors that belonged to the United Methodist Church in Indiana, the DePauw University Archives and Special Collections are keepers of the Indiana United Methodist Church Archives.

There is also the Indiana, U.S., United Methodist Church Records, 1837-1970 available through Ancestry.

Roman Catholic

To find Roman Catholic records for ancestors, start by contacting the church (parish) of interest. The Archdiocese of Indianapolis provides some guidance for Roman Catholic genealogy search in Indiana. The Archdiocese of New Orleans has provided access to records for the years 1718-1815 online. The Archdiocese of Boston and American Ancestors have partnered to provide records for the years 1789-1920 online (registration for a free account with American Ancestors is needed to view the records).

Quaker (Religious Society of Friends)

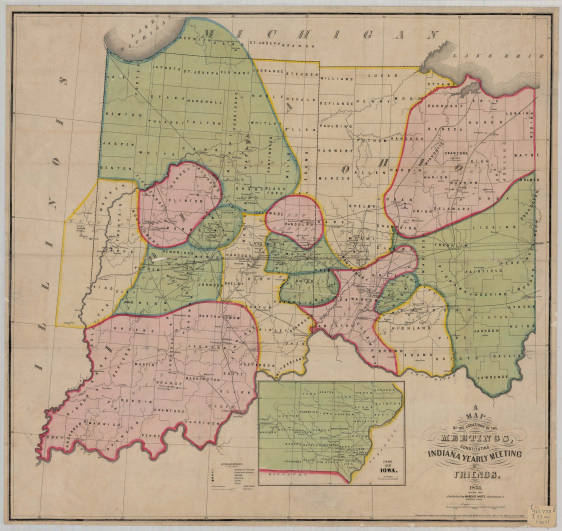

A map of the locations of the meetings, constituting Indiana yearly meeting of Friends. Image: Indiana State Library Digital Collection.

Quaker Archives for the state of Indiana can be found in the Friends Collection and College Archives at Earlham College. Try searching the Friends Manuscript Series record group, Friends Record Group and Names. When visiting the archives in person, please make a research appointment via email three business days before arriving.

For Quaker research outside the state of Indiana, try the Haverford College Quaker and Special Collections. To research in person, contact the staff via email before a visit. Researching at home, try Haverford Colleges’ online obituary index: the Quaker Necrology Database. To search index, select “obituary index” located on the top bar of the page.

Protestant Episcopal Church

St. James Church, South Bend, Indiana. Image: The Church Record, April 1895, page 2; Indiana State Library Digital Collections.

A healthy collection of online records for the Protestant Episcopal Church can be found from the Protestant Episcopal Church of Northern Indiana Archives.

To find Church records in other states besides Indiana; try the Colonial Society of Massachusetts for many online Massachusetts church records. The New England’s Hidden Histories: Colonial-Era Church Records contains an online collection of Congregational church records for early New England. For online Maryland church records covering all denominations, there is The Bob Fout Collection of Frederick County, MD Church Records.

Finally, a useful source for all things religious there is the Duke University Divinity School’s Divinity Archive.

Hopefully, these resources and search methods will help you discover your ancestors’ church records and aid you in your overall genealogical endeavors.

This blog post is by Angi Porter, Genealogy Division librarian.