Sometimes in genealogy research, the pieces just don’t come together. No one seems to be living where you expect them to be, records have gone missing and you just can’t make any connections between generations.

Although not exhaustive, this guide introduces some search techniques that may help you find those elusive ancestors.

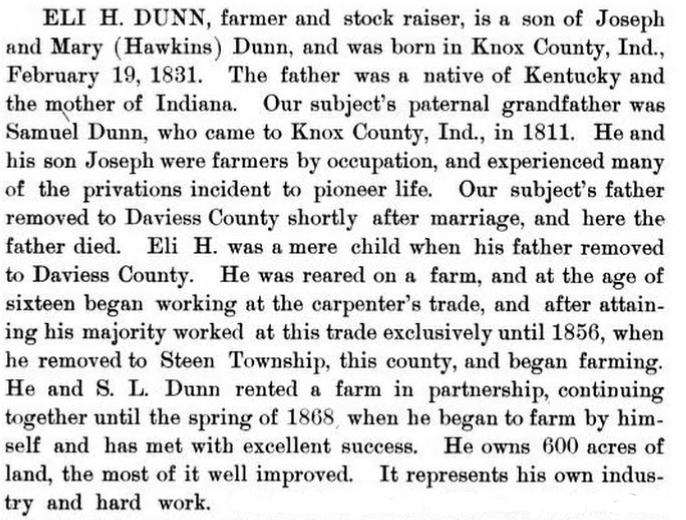

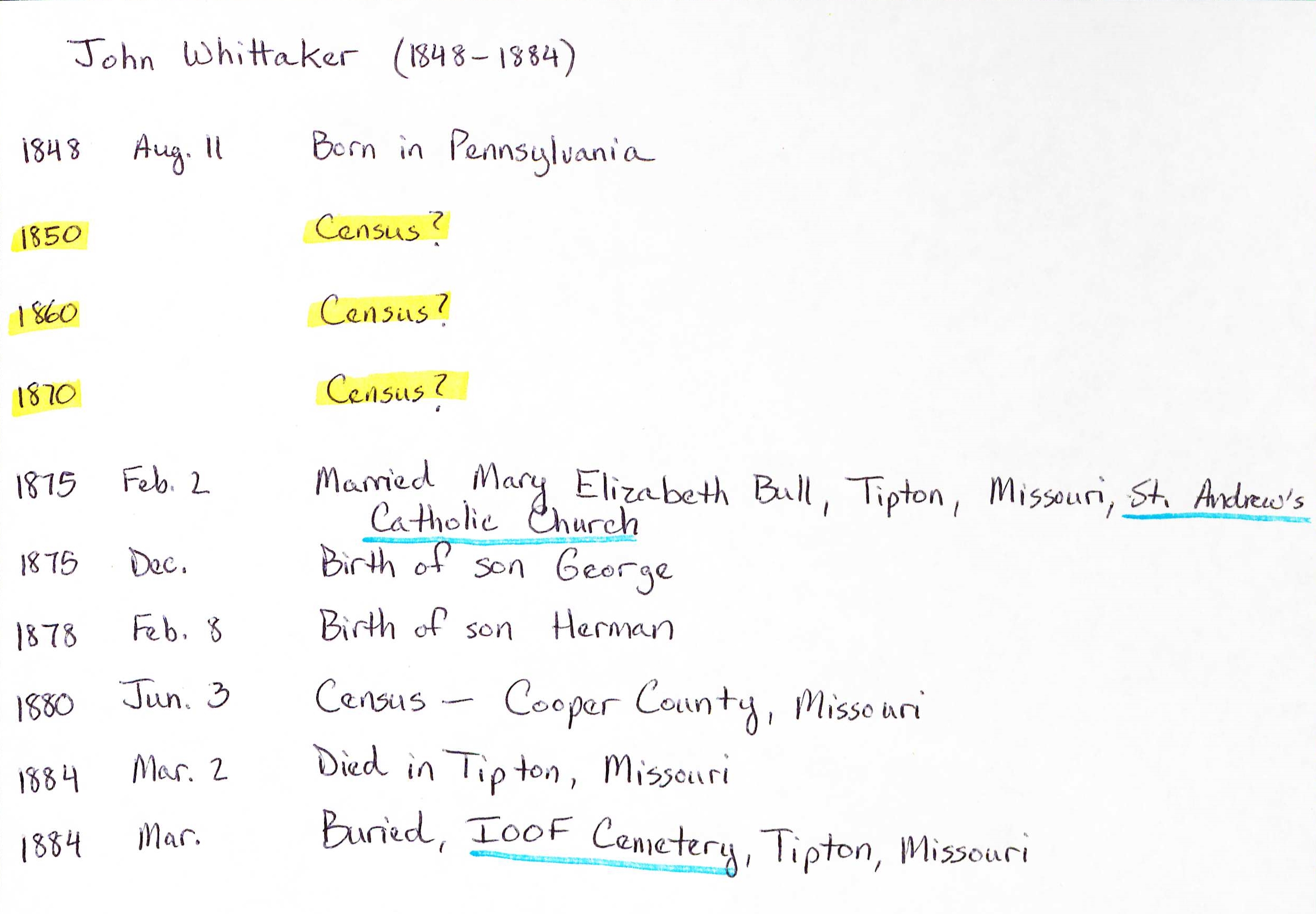

Write down everything you know about the person.

Writing down his or her life events in chronological order shows where you may have gaps in your research, such as census records you have not yet found. A timeline also suggests places to look for additional records if your ancestor lived through a war or other major historical event. Noting the places where your ancestor lived provides clues to the geographic area where your ancestor’s parents may be found.

Filling in those three missing censuses may well hold the key to John Whittaker’s family. Note the place of birth as Pennsylvania, meaning John’s parents lived there at some point. Also note the biographical details of marriage in a Catholic church and burial in an Independent Order of Odd Fellows cemetery.

Don’t just note places of residence. Fill in social details such as religious affiliation, political affiliation, club and society membership and other details you may know about your ancestor. These details will be useful later.

Looking at your timeline, information such as your ancestor’s birth date and place provides indirect details about his or her parents. For example, the place of birth tells you where the family was living at the time, while the date of birth tells you the minimum likely age of the parents.

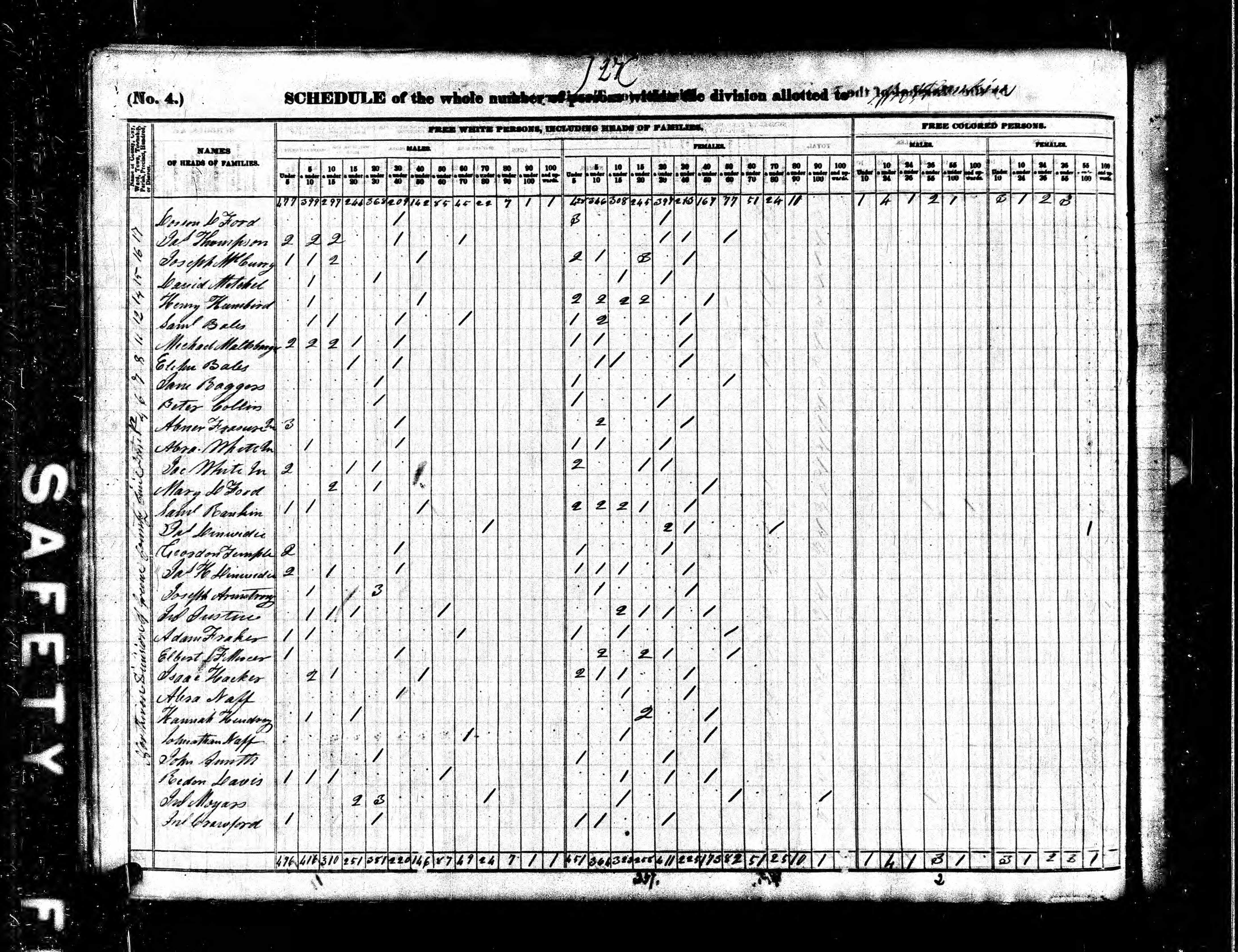

Look at the pre-1850 censuses.

1840 United States Federal Census. Greene County, Tennessee. Accessed July 9, 2018. Ancestry Library Edition.

The early censuses are often overlooked because they do not provide the level of detail of later censuses. However, these records are not completely unhelpful to genealogists. If your ancestor was old enough to be an adult in these censuses, look for him or her. Women in the pre-1850 censuses are more difficult to find, as they were not often heads of households, but they do turn up occasionally.

If your ancestor was still a child in 1840 or earlier, if you know where he or she was living in 1850 or if you know where he or she lived as a child, search the censuses in that area for individuals with the same last name. Try tracing those individuals to the 1850 census or later to see if they could be related to your ancestor. Also look at the family composition of the various households with your ancestor’s surname in the early censuses to see if there is a male or female of the appropriate age.

Make sure you have found all relevant censuses.

If you are trying to connect your ancestor to his or her parents, do not look at censuses in which he or she is a child only. Sometimes elderly parents lived with their adult children, so you may be able to find the parents there. Also depending on the census, you may find further clues concerning your ancestor beyond just age and place of birth.

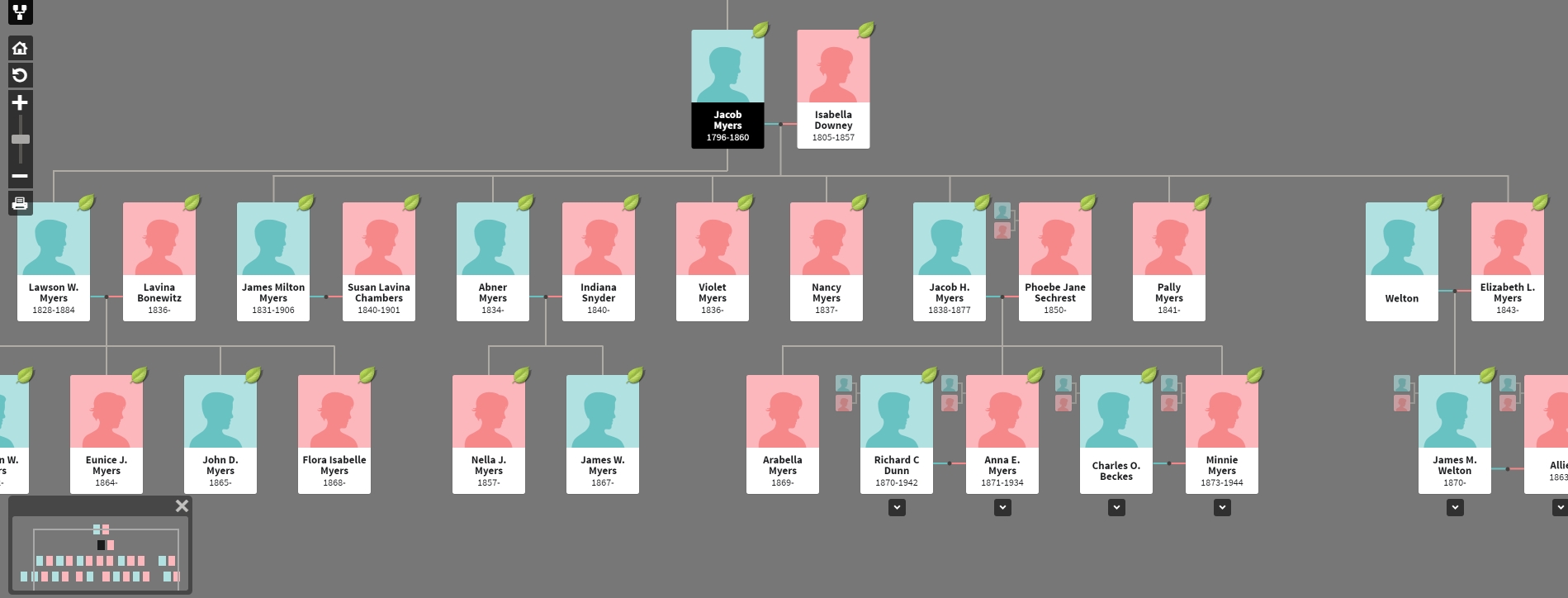

Trace the siblings of your ancestor and their descendants.

Jacob Myers family tree. Ancestry.com user casvelyn. Accessed July 9, 2018. Ancestry Library Edition.

Sometimes the siblings of your ancestor provide more detailed information than your ancestor with regard to parentage. Maybe a younger sibling had a death certificate, whereas your ancestor died too early. Perhaps one or both of the parents are living with a sibling in later censuses. Another sibling’s family could have written a more detailed obituary. Looking at the siblings’ birth information can also provide evidence for other places your ancestor’s family may have lived, particularly if the family moved frequently.

Look in the county records where your ancestor lived throughout his or her life.

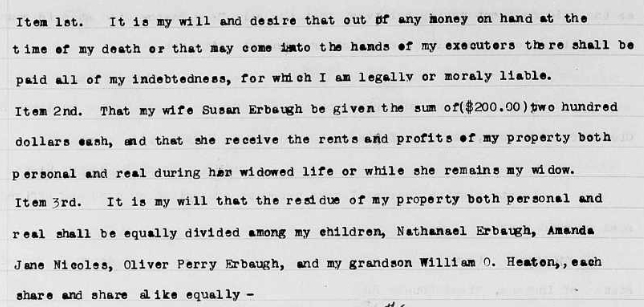

County records such as wills, probates, deeds and court records are full of direct and implied relationships. Will and probate records outline what happened to a person’s property after he or she died. Although many people did not write a will, most owned enough property to have the estate go through the probate process. If your ancestor died young, he or she may have left property to his or her parents. Otherwise, looking at wills and probates for individuals with your ancestor’s surname may help you to find his or her parents, grandparents, aunts, uncles or siblings.

Will of Philip Erbaugh. Clerk of Court, Miami County, Indiana, Vol. 8, p. 66. Accessed July 9, 2018. Family Search.

Deed records do not always name the relationship between the seller and the buyer, but there are some family clues to be found. If someone sells a piece of property for $1 or “for love and affection,” there is a good chance of a family relationship between the individuals.

Criminal and civil court records may note familial relationships if someone sued other members of his or her family or if a family member testified at a trial or helped to pay bail or fines. Court records are rarely indexed by the names of all involved, just the plaintiffs and defendants, so looking at cases involving individuals with the same surname as your ancestor may be necessary.

Check county histories.

Most county histories contain a section of brief biographies of local residents. Even those that do not usually contain information on early or prominent residents of the area. These biographical sketches provide many details about your ancestor’s life, including spouses, children, parents, career, education and social affiliations. Many county histories are available online through sites such as Google Books, Internet Archive and Hathi Trust.

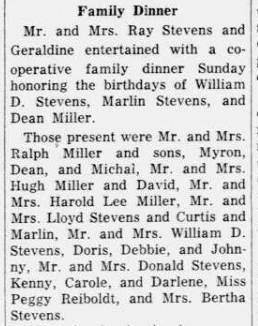

Look at newspapers.

As more and more newspapers are digitized and indexed, it is easier than ever to search the newspapers for your ancestor. Through newspapers, you may be able to find an obituary or death notice for your ancestor. You also may be able to find articles about religious or social affiliations. For example, if your ancestor attended a Methodist church picnic or helped out at a Masonic Lodge fish fry, he may have been a member of that church or fraternal organization. Depending on the area, newspapers may also contain information about vacations, hospital stays, weddings, funerals and many other everyday aspects of your ancestor’s life that cannot be found anywhere else.

Check online trees.

Looking at family trees that other researchers have posted online can help you to see if you have overlooked anything in your research. Try to use trees that have citations so you know where the person got their information. If the trees do not have citations, but do contain new information, think about sources that might provide that information and check them to see if you can find proof.

There are many websites where individuals can post family trees, so you may need to check more than one to find new information about your ancestor. Simply searching for “[ancestor name] family tree” or “[surname] family tree” can find many trees that are publicly available.

This blog post is by Jamie Dunn, genealogy librarian. For more information, contact the Genealogy Division at (317) 232-3689 or send us a question through Ask-a-Librarian.