This blog article should be considered general information and should not be construed as legal advice. The article reflects Indiana law at the time the article was written, but may not include every detail or nuance and may not reflect the law in other jurisdictions. Additionally, laws frequently change. The reader should not act on the information contained in this article but rather should act on the advice of his/her own legal counsel or other appropriate professional.

Periodically, the Indiana State Library receives requests for information about whether library staff have an obligation to report suspected child abuse. This Q & A attempts to address the most common questions regarding this subject.

Image courtesy of Pixabay (https://pixabay.com).

Are library staff required to report suspected child abuse or neglect?

(See IC 31-33-5-1 through IC 31-33-5-4)

Yes, an individual who has reason to believe that a child is a victim of child abuse or neglect is required to make a report to the Department of Child Services (DCS) or local law enforcement. Furthermore, if an individual is required to make a report in the individual’s capacity as a member of the staff of a public institution/agency, the individual is required to immediately notify the person in charge of the institution/agency (in this case, the library director) or must notify the library director’s designated agent. The library director, or the director’s designated agent, must make a report (or cause a report to be made) to DCS or local law enforcement. The staff person who personally observed the child who is suspected to be abused or neglected is only excused from making his/her own report if the staff person knows the director or the director’s designee made the report.

How should such reports be made? (See IC 31-33-5-4)

Reports must be made orally and immediately to either DCS or local law enforcement. Currently, DCS operates a hotline that is staffed 24-hours a day for the purpose of receiving such reports of suspected child abuse or neglect. The phone number is 1-800-800-5556. You could also call directly the local DCS office for the county in which your library is located.

Our library has a patron privacy policy. Doesn’t reporting suspected child abuse or neglect violate our patrons’ privacy?

The law always trumps local policy. Suspected child abuse and neglect must be reported. The library could consider amending the privacy policy to address that patron privacy is automatically waived in cases of suspected child abuse or neglect.

What if I am not sure if the child is being abused or neglected? (IC 31-9-2-101)

You don’t have to be sure. Actual knowledge is not required by the law, nor do you have to have a high level of certainty. If you have reason to believe a child may be abused or neglected, make the report and let DCS determine if the report is substantiated. “Reason to believe”, for the purpose of the child abuse and neglect reporting laws, means “evidence that, if presented to individuals of similar background and training, would cause the individuals to believe that a child was abused or neglected.”

Is the library or library staff at any risk of legal liability for reporting suspected abuse or neglect if the report is later found to be unsubstantiated by the Department of Child Services? (See IC 31-33-6-1 through IC 31-33-6-3)

Unless a report is made in bad faith, individuals who report suspected child abuse or neglect are immune from civil or criminal liability relating to their making the report. The law presumes a person making such a report was acting in good faith.

Are there consequences for not reporting suspected abuse or neglect?

(See IC 31-33-22-1 & IC 35-50-3-3)

Failure to report suspected child abuse or neglect is a class B misdemeanor punishable by up to 180 days in jail and a fine of up to $1,000.

I am concerned about retaliation from the family I reported, should I be concerned?

(See IC 31-33-18-1; IC 31-33-18-2; IC 31-33-18-5)

The names of individuals who report suspected child abuse or neglect to DCS are not supposed to be divulged by DCS. Library employees are not required to inform the parents that a report was made to DCS about the parents’ child. The audio recordings of calls made to the child abuse hotline are confidential and may be released only upon court order. Additionally, according to the DCS website, people who make reports of suspected abuse or neglect to DCS may remain anonymous.

Update: As of July 1, 2017, the following changes have been made to the child abuse and neglect reporting laws:

- Previously, reports of suspected child abuse or neglect were required to be made orally. Now, reports of suspected child abuse or neglect may be made in writing or verbally.

- The law now prevents public institutions, agencies, schools and other entities from establishing a policy that restricts or delays the duty of an employee or individual to make a report of suspected child abuse or neglect.

- The law slightly modifies the reporting process when someone makes an “on the job” report as an employee of a public institution. Previously, the employee was required to notify the individual in charge and the individual in charge had an obligation to make the report. Now, the report must be made by the employee first, and then the employee must notify the individual in charge of the public institution, agency, school, etc.

This blog post was written by Sylvia Watson, library law consultant and legal counsel, Indiana State Library. For more information, email Sylvia at sywatson@library.IN.gov.

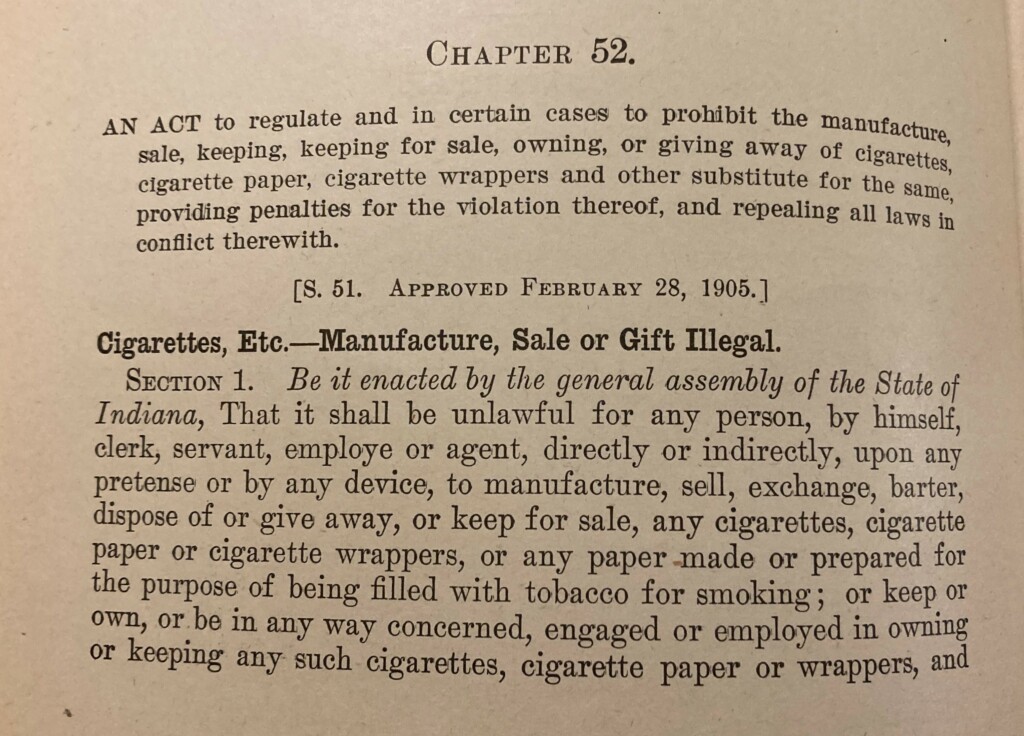

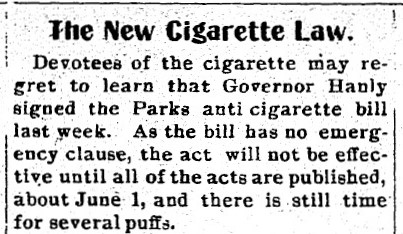

The law was in place until 1909, when it was amended. The new law narrowed the prohibition of cigarette sales and use to just minors. Currently, Indiana and federal law have the age set at 21.

The law was in place until 1909, when it was amended. The new law narrowed the prohibition of cigarette sales and use to just minors. Currently, Indiana and federal law have the age set at 21. Luther H. Higley began publishing the No-Tobacco Journal in Butler, Indiana in January 1918 for the No-Tobacco League of America. Higley was the owner and operator of the Butler Record, a local newspaper. He had an established career as a printer and publisher. Higley also had an affiliation with the Methodist Church in Butler and published the Epworth League Quarterly which had national circulation.

Luther H. Higley began publishing the No-Tobacco Journal in Butler, Indiana in January 1918 for the No-Tobacco League of America. Higley was the owner and operator of the Butler Record, a local newspaper. He had an established career as a printer and publisher. Higley also had an affiliation with the Methodist Church in Butler and published the Epworth League Quarterly which had national circulation. World No Tobacco Day was created in 1987 by the Member States of the World Health Organization to draw attention to preventable disease and death caused by smoking. World No Tobacco Day is May 31.

World No Tobacco Day was created in 1987 by the Member States of the World Health Organization to draw attention to preventable disease and death caused by smoking. World No Tobacco Day is May 31.