Born on May 26, 1805, in Petersburg, Virginia, Angelina Maria Lorain – or Lorraine – was raised as a Methodist and instilled with ideas of abolitionism. After marrying James Collins – and taking his name – in 1830, the couple moved to Paoli, Indiana, where they lived for a few years before settling in New Albany in Floyd County.

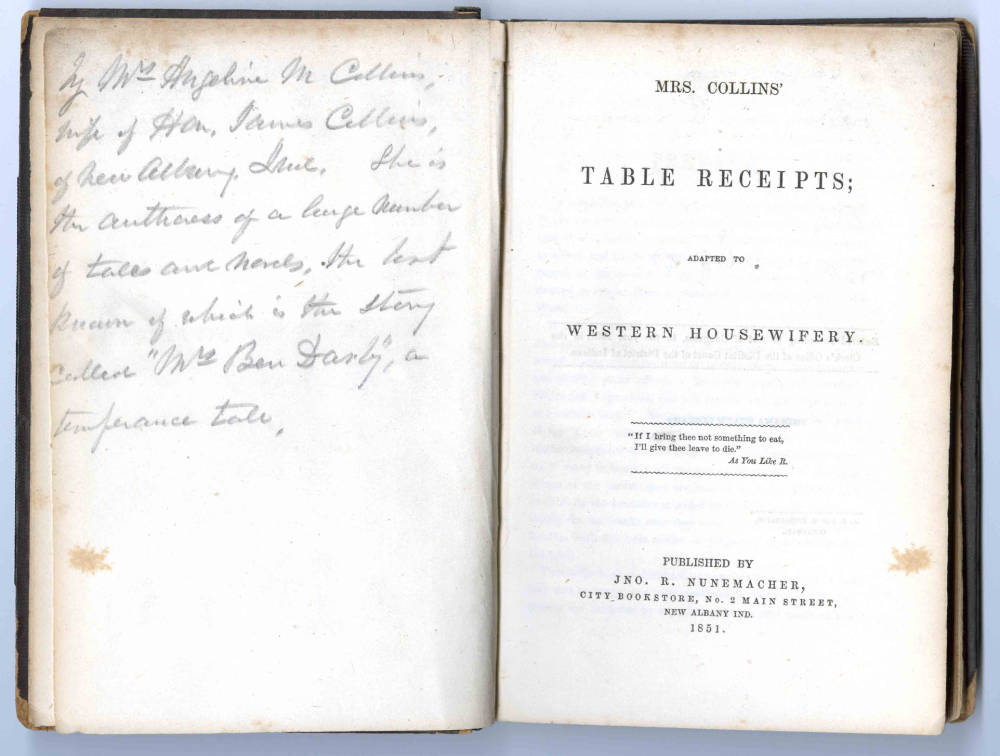

In 1851, Angelina Collins, with the help of John R. Nunemacher, printer and book seller in New Albany, published her volume of table receipts – known today as recipes – titled “Mrs. Collins’ Table Receipts: Adapted to Western Housewifery.”

In the preface of the book, she explains “…my object has been to simplify the culinary art, and adapt it to every capacity and condition of life, and in preparing the receipts, I have endeavored to select and combine such ingredients as may be easily obtained in any section of our country, but especially have I desired to render them serviceable to the housekeepers of the West.” In other words, “Here’s what you can find at local markets and groceries in late 1840s southern Indiana.” Being on the Ohio River, many of the river towns would have access to a far greater variety of imported goods from the eastern coast, with grocers and merchants being among the first businesses to be established.

Collins ends her preface with “To the ladies of the West, I offer this little volume with full confidence that it will be properly appreciated and well received, and should it in any manner add to their comfort or convenience, I shall be fully compensated for the employment of my leisure home.” And her little volume must have added a large amount of comfort and convenience because in 1857, her cookbook was republished after somehow making its way to A. S. Barnes & Company in New York, where it experienced a name change to the title “The Great Western Cookbook, Or Table Receipts Adapted to Western Housewifery” with the same number of pages. By this time, 1850s southern and middle Indiana would have been well settled, but the upper part still remained as open territory for settlers. These types of publications, such as Mrs. Collins’ cookbook, were meant to encourage immigration to those areas and further west, by showing that there is an abundance of resources.

Here at the Indiana State Library, we have the original 1851 volume and have added it to our digital collections. You can view it here.

The 1857 version is available online to be researched in Indiana University’s digital collection, “Service through Sponge Cake”. Here is a link to that version.

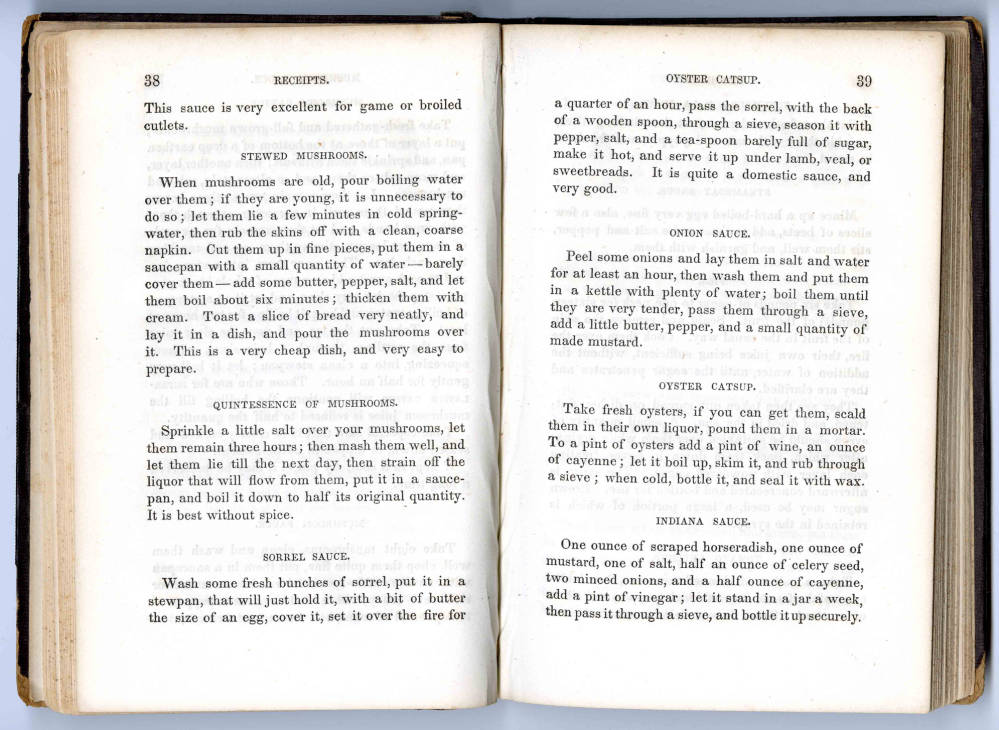

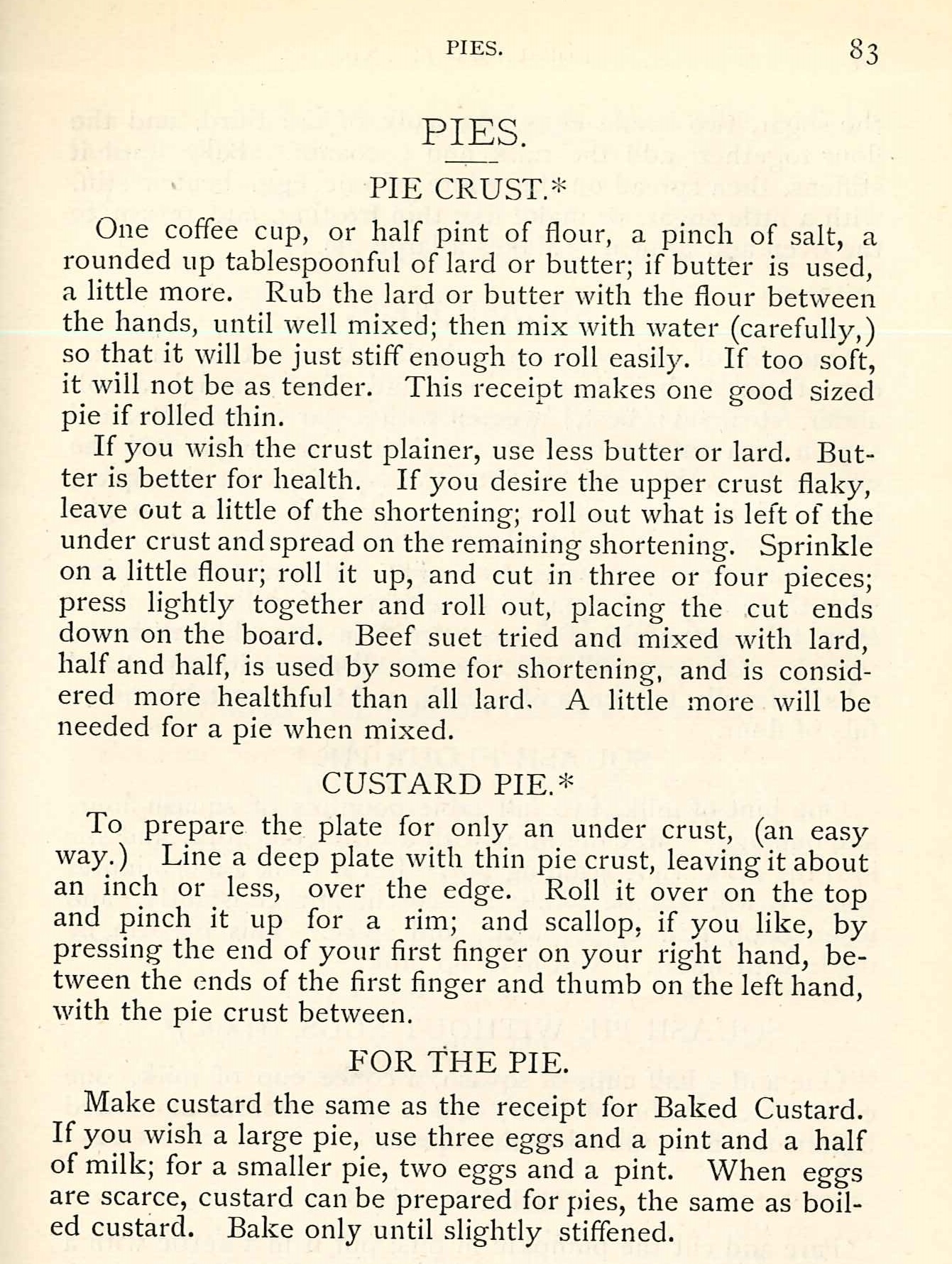

So, if you love trying our historic recipes, there are 140-plus pages for you to sample. Collins organized her book by topics, including fish, boiling, pickling, pies and fancy dishes to name a few. And of course, no cookbook would be complete with tidbits of information or advice. On page 15, “Observation – In preparing soups, always cut the pieces of meat you send in the tureen small enough to be eaten with introducing a knife and fork into the soup plate.”

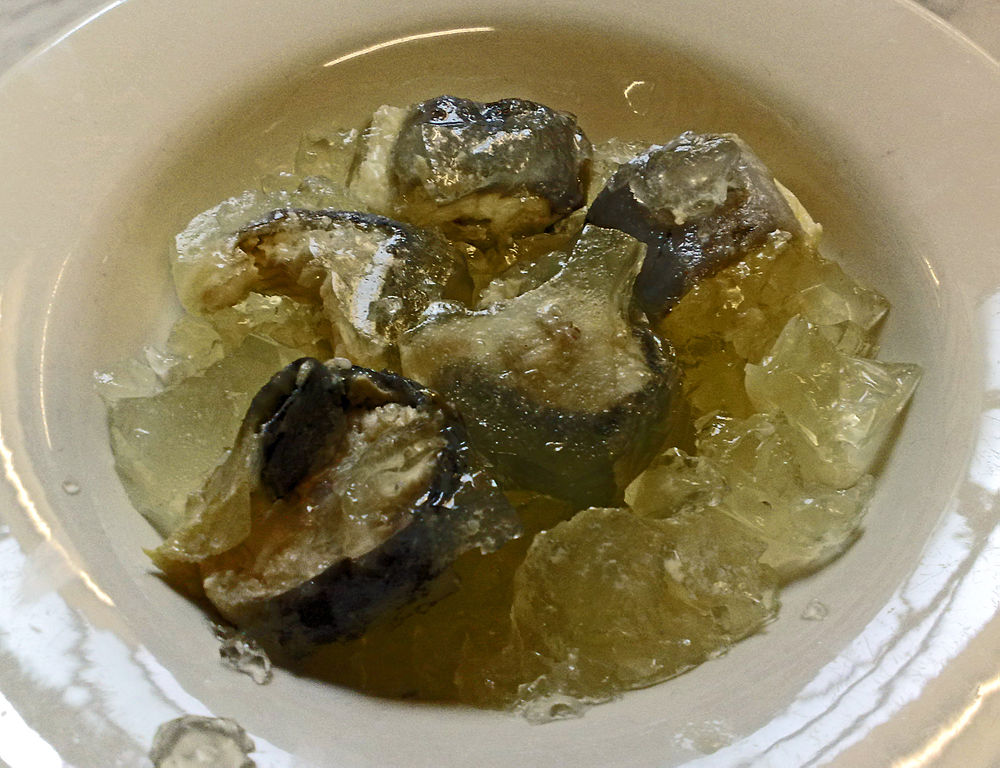

Her recipes include corn pone, hominy, “Succotash a la Tecumseh,” mock turtle soup, “California soup,” Mrs. Collins’ batter cake and brain balls. Collins also includes a recipe for mangoes, or in today’s language, stuffed bell peppers. Also included is an interesting recipe for “Indiana sauce.”

Although Angelina Maria Collins died on Sept. 28,1885 in Salem, Indiana, her cookbook is still being researched and used by historians.

Are you interested in historic cookbooks? If so, here are some digital collections of historic cookbooks available from libraries around the country:

- Indiana State Library’s Digital Collections.

- Service through Sponge Cake.

- Community Cookbooks: An Online Collection.

- Recipe for Victory: Food and Cooking in Wartime.

- Feeding America: The Historic American Cookbook Project.

- Culinary History and Cookbook Digital Archive: Explore the second largest collection of cookbooks in the nation.

This post was written by Christopher Marshall, digital collections coordinator for the Indiana Division at the Indiana State Library.