If you’ve gone through a box of older relatives’ papers, you may have run across a flyer that mentioned an estate and that the heir of the estate were due millions of dollars. The paper would have mentioned ongoing litigation and that the end of suit was in sight. It would have also asked the reader to help assist with these lawsuits by sending money to the leaders of the suit. Unfortunately, the unclaimed millions mentioned didn’t exist. In some cases, neither did the estate. They were all a scam to fleece people out of their savings with the promises of easy money.

There have been numerous cases of estate fraud over the centuries in the U.S. One of the earliest and most well-known is related to the Anneke Jans Bogardus Estate in New York City. The land in question was a 62-acre farm where Trinity Church currently sits. The first suit was brought in 1749 by a descendant of Cornelius Bogardus who died before the land was sold and did not sign the deed transferring the land. Both the descendant, Cornelius Brower and his son John filed multiple claims with the ruling always going to Trinity.

Other estate fraud cases include the Col. Jacob Baker estate in Philadelphia 1930s and the Sir Francis Drake estate. Approximately 2 million dollars was collected to help settle the Drake estate and the leader of the scam, Oscar Hartzell, was convicted of fraud and sentenced to ten years in Leavenworth penitentiary.

One of the aspects of the scam was fraudulent documents, usually a will or deed created to attach a person to the property in question and would be mentioned at meetings of heirs and in newsletters. False pedigree charts and books were often created as well to connect unrelated persons to one another, only a more dedicated genealogist would find the discrepancies when going through the information. Even after the scam was revealed, the false pedigree information lived on in published family histories.

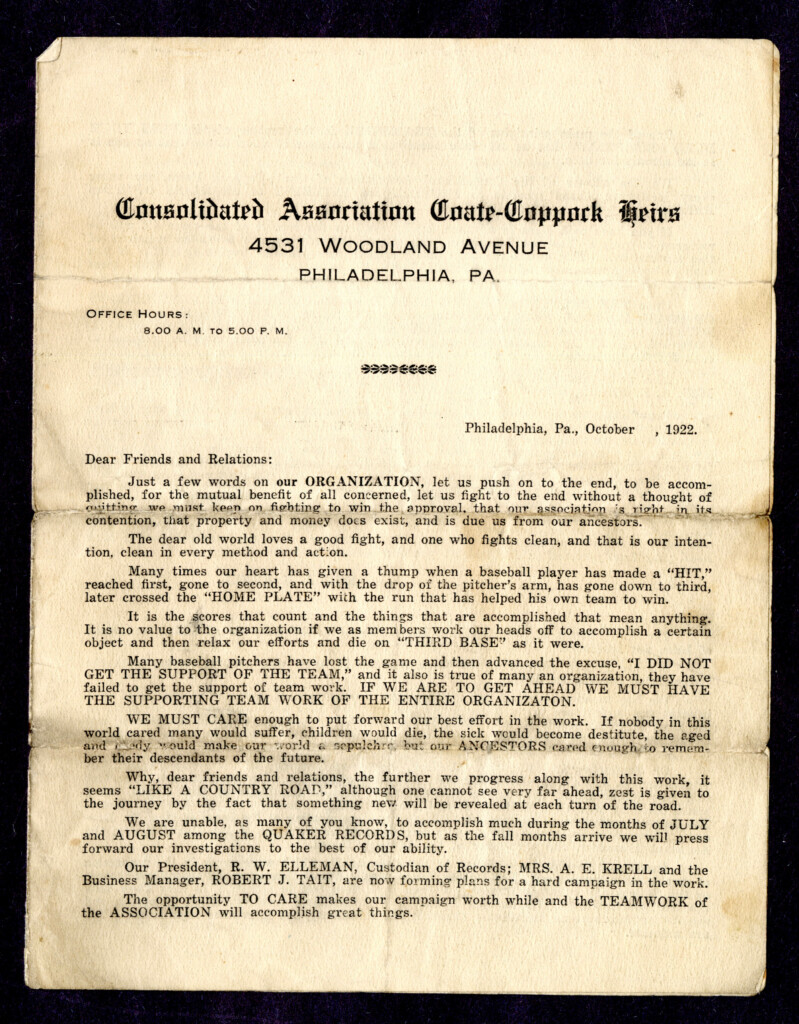

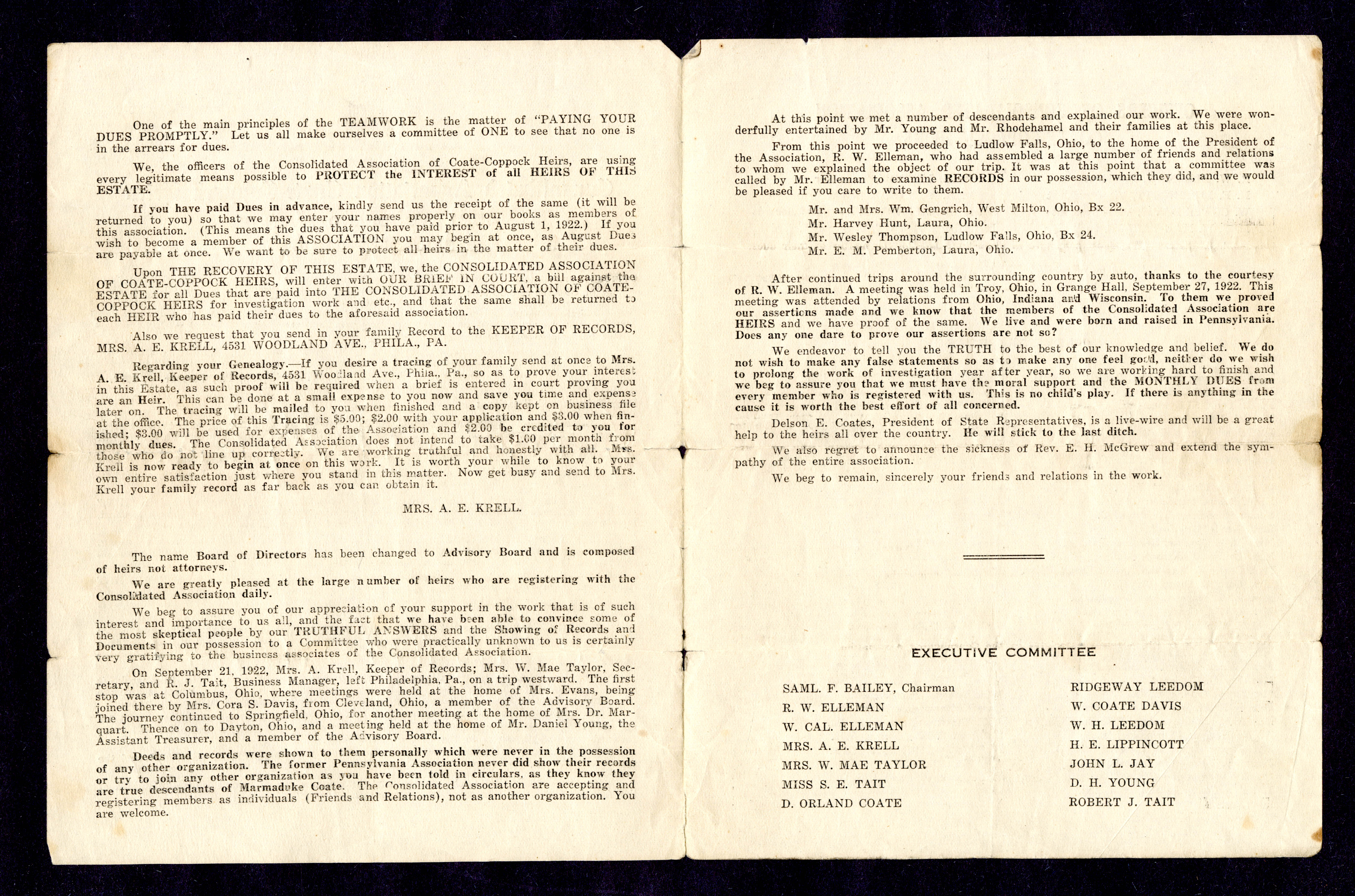

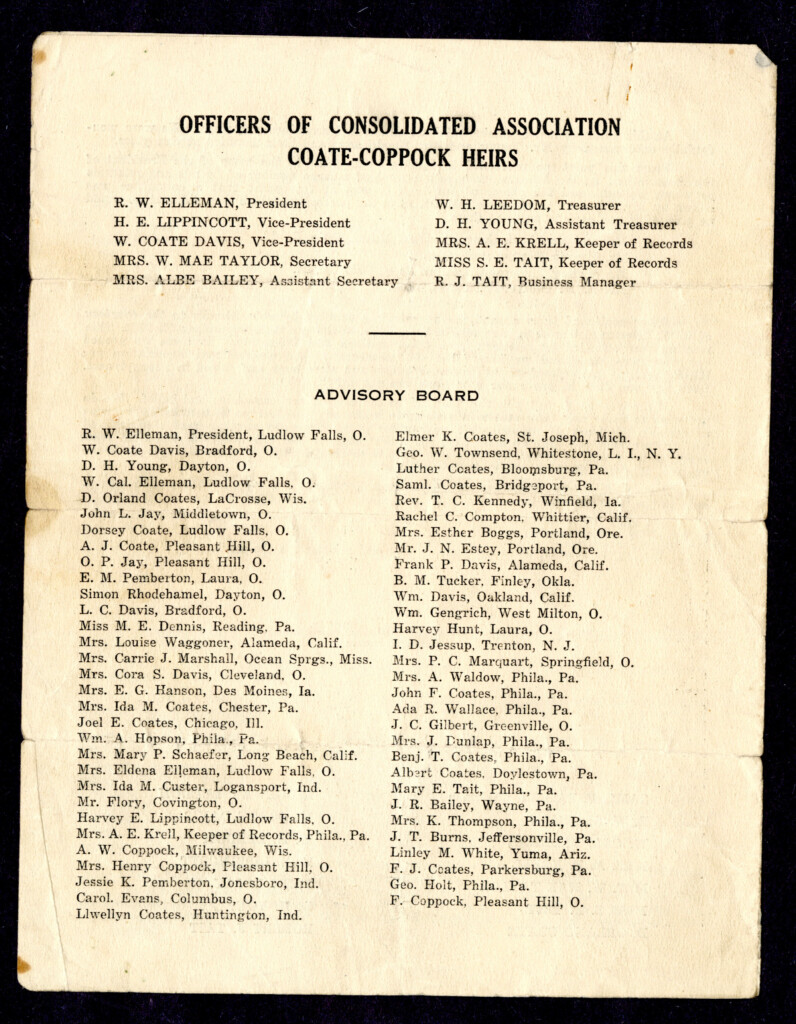

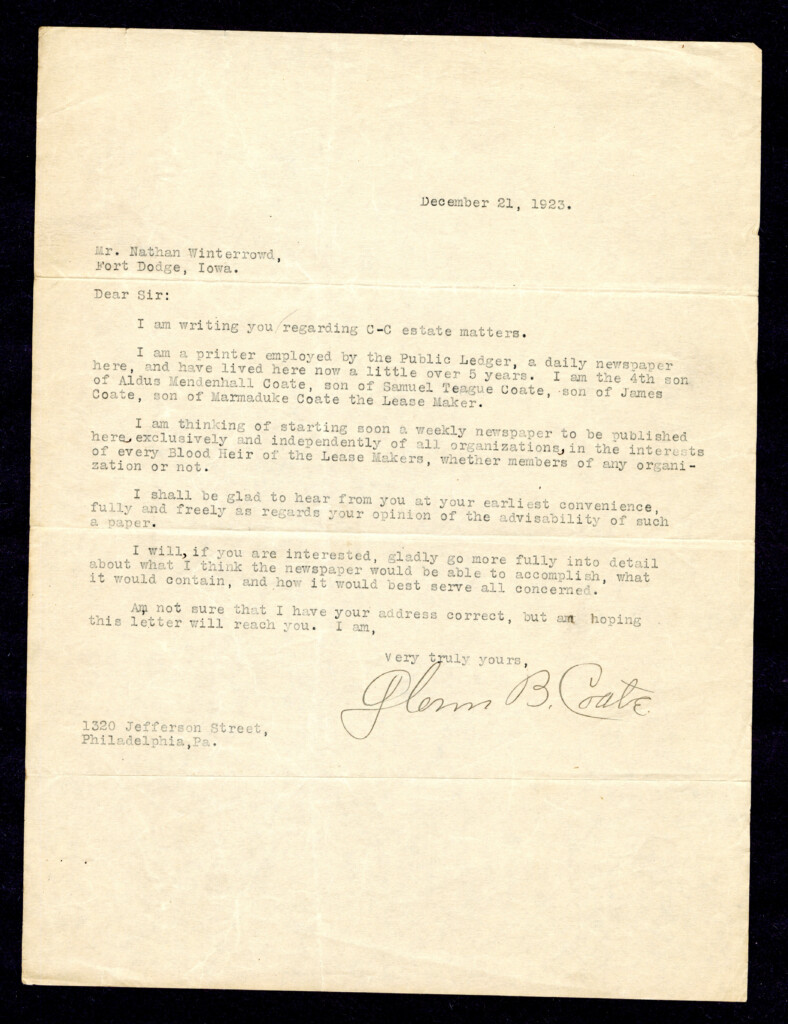

The Vern A. Carpenter Collection at the Indiana State Library has six folders dedicated to the Coate Coppock Estate. The Coate Coppock estate was hinged on a 99-year lease to property in central Philadelphia that belonged to Marmaduke Coate and Mary Jane Coppock. The lease covered 976 acres in Philadelphia, along with 5,000 acres in multiple counties in Pennsylvania. Fliers were sent out to people making them aware of the “unclaimed” lease and asking them to support the cause. Local newspapers ran articles about meetings of the heirs. Amanda Krell, along with Glen B. Coate, were ringleaders of the scam.

In the folders are papers from Nathan Winterrowd of Fort Dodge, Iowa. Winterrowd was mentioned in a few newspaper articles in 1922 trying to raise money for the estate and get more claimants to join. Numerous signed affidavits from other family members detailing relationships along with other vital information take up most of the first two folders. Correspondence, newsletters and pamphlets about the Coate and Coppock estate are also included.

The other folders contain correspondence to and from Vern Carpenter and different agencies of the U.S. government, FBI, U.S. district attorney for Pennsylvania, U.S. Post Office, Herbert Hoover Presidential library, the Bureau of prisons and the commonwealth of Pennsylvania, along with several other libraries and state and federal agencies.

Carpenter was researching the Wenderoth – and related names – family when he came across Nathan Winterrowd in the newspaper and the Winterrowd connection to the Coate and Coppock estate. He started looking into what the family connection was to the estate. He spoke with one of the original attorneys who managed the estate, Harry S. Monell, who was engaged to Amanda Krell in May of 1920. He mentions Winterrowd and how they had him arrested on a couple of occasions but was generally evasive about what happened to the association after he resigned.

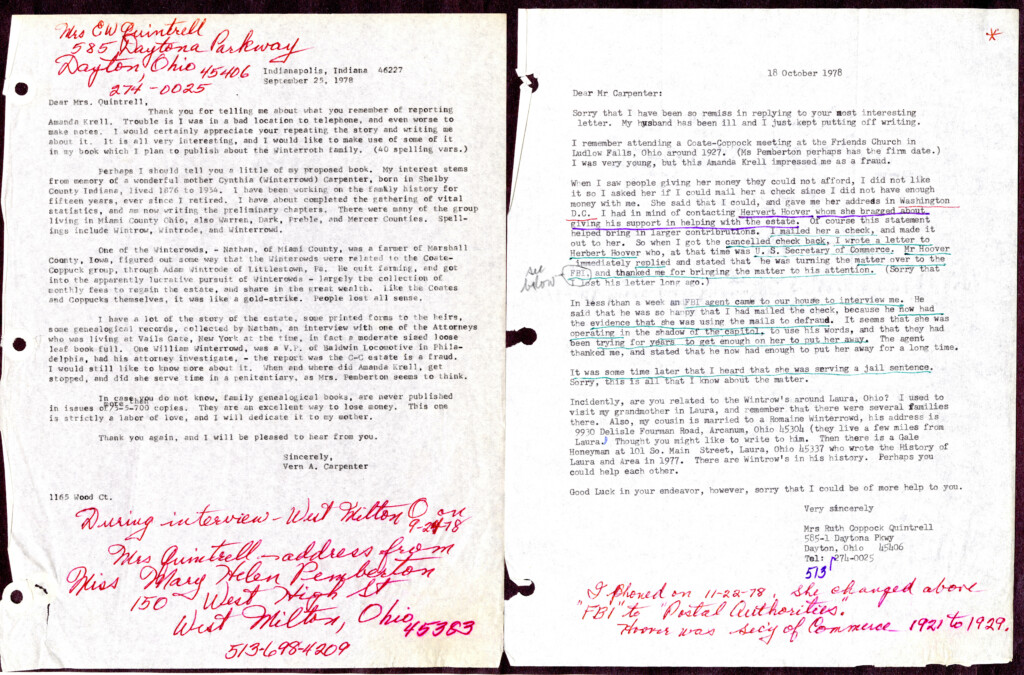

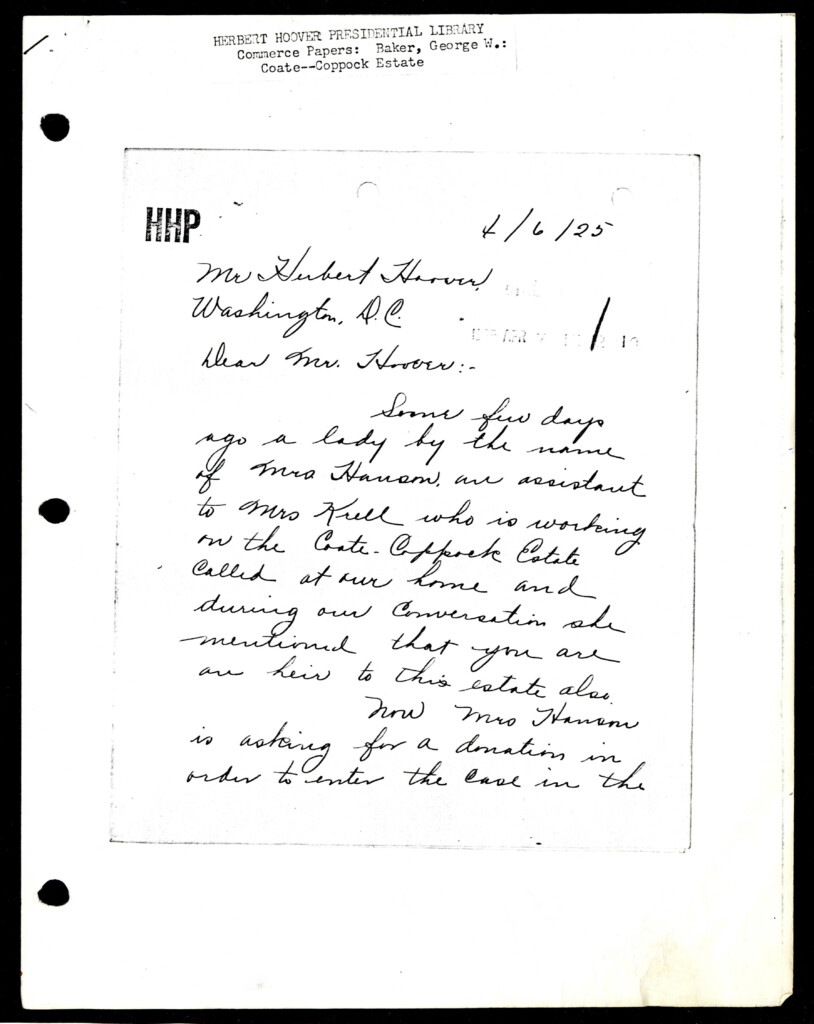

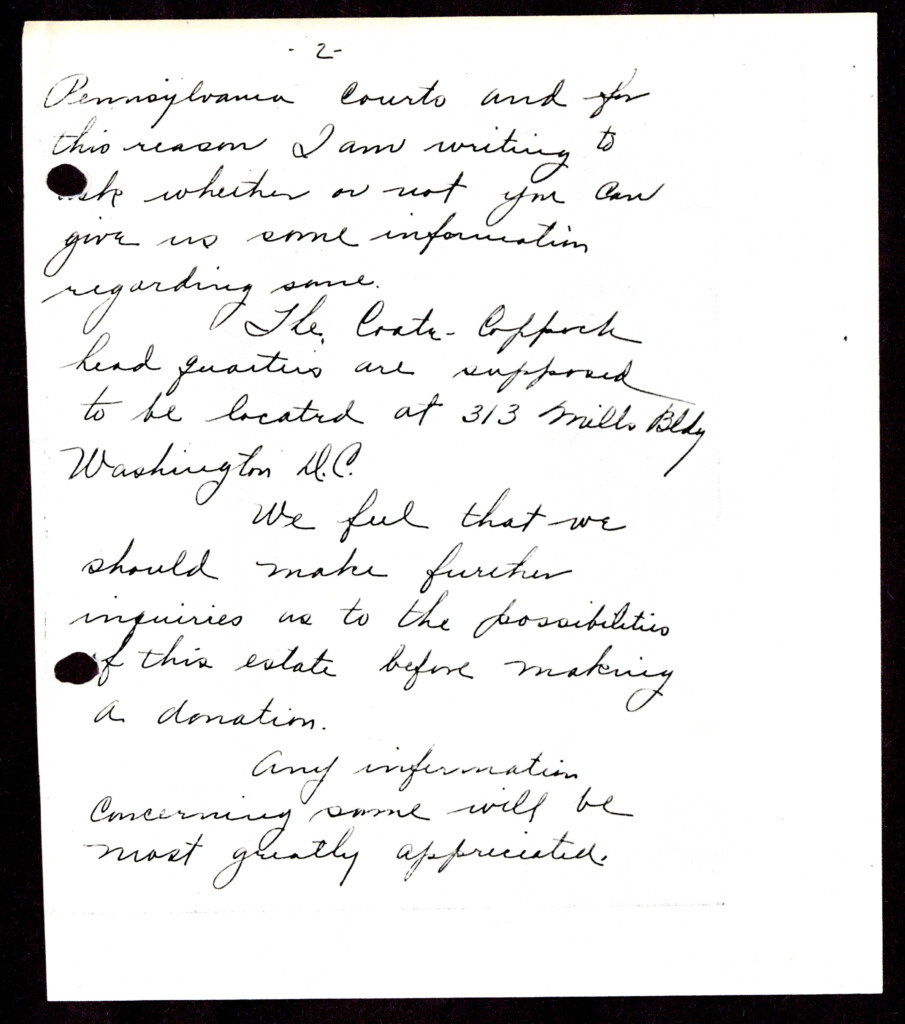

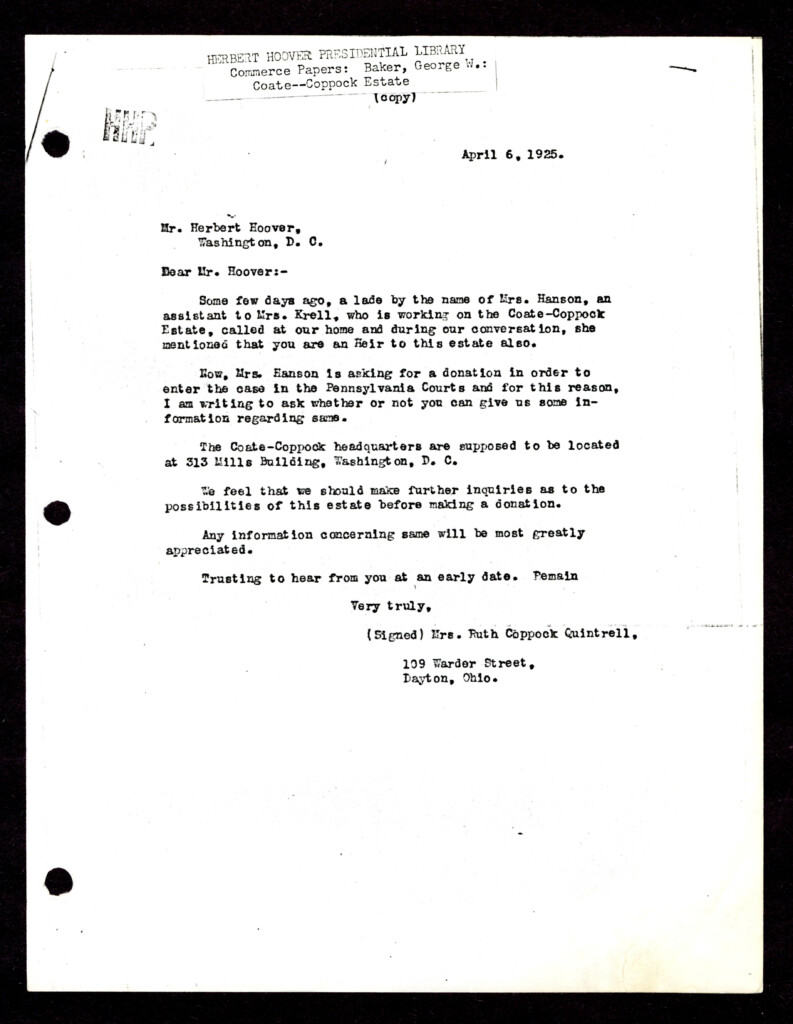

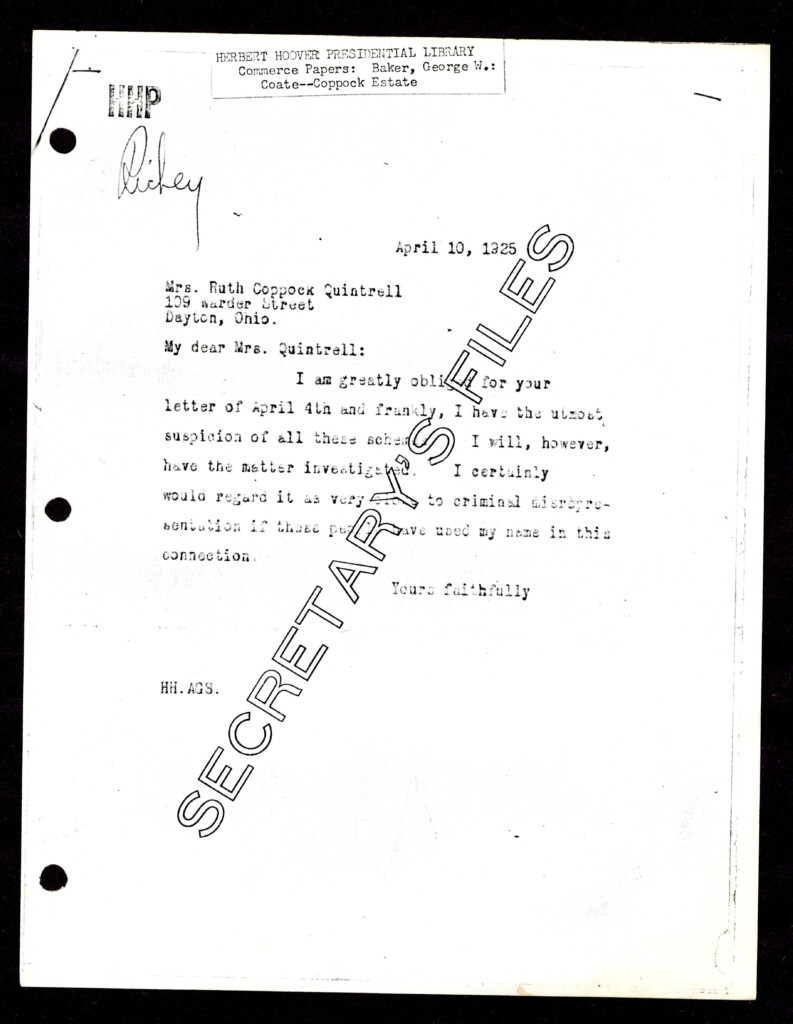

While talking with another genealogist, he was put in touch with a woman, Ruth Quintrell. During an interview, she mentions she attended a Coate and Coppock heirs meeting and after listening to Krell, Quintrell suspected Krell was a fraud. She mailed a check to the association and then sent the returned check along with correspondence to Herbert Hoover, the Secretary of Commerce at the time, thus starting the federal investigation into the Coate and Coppock Association.

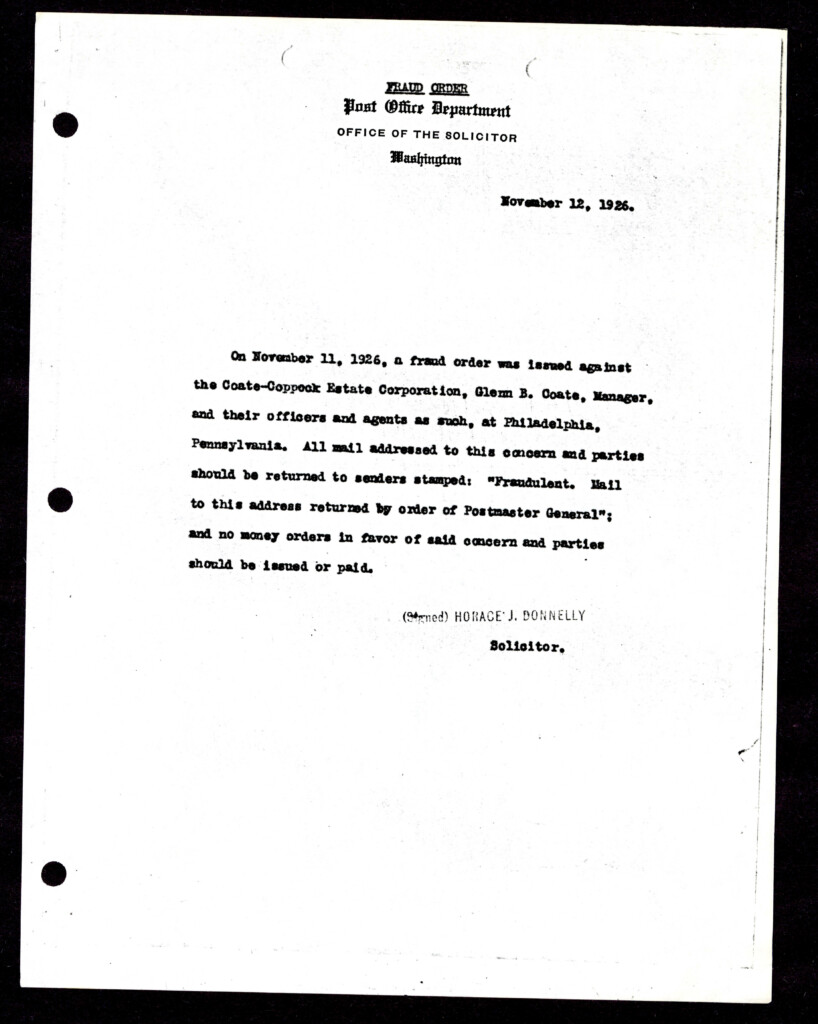

Carpenter spends his time contacting various state, and federal agencies, libraries and archives looking for information about the case and finding out what if anything happened to Amanda Krell and Glen B. Coate. His first big break is from the Herbert Hoover Presidential library. The library sent him 34 pages from a folder that also contained correspondence into the Baker Estate. After contacting a family member who works for the federal government Vern finds out case files from the Coate and Coppock Estate are held at the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia. There are also records from the U.S. Postal Department that go into the investigation of the association.

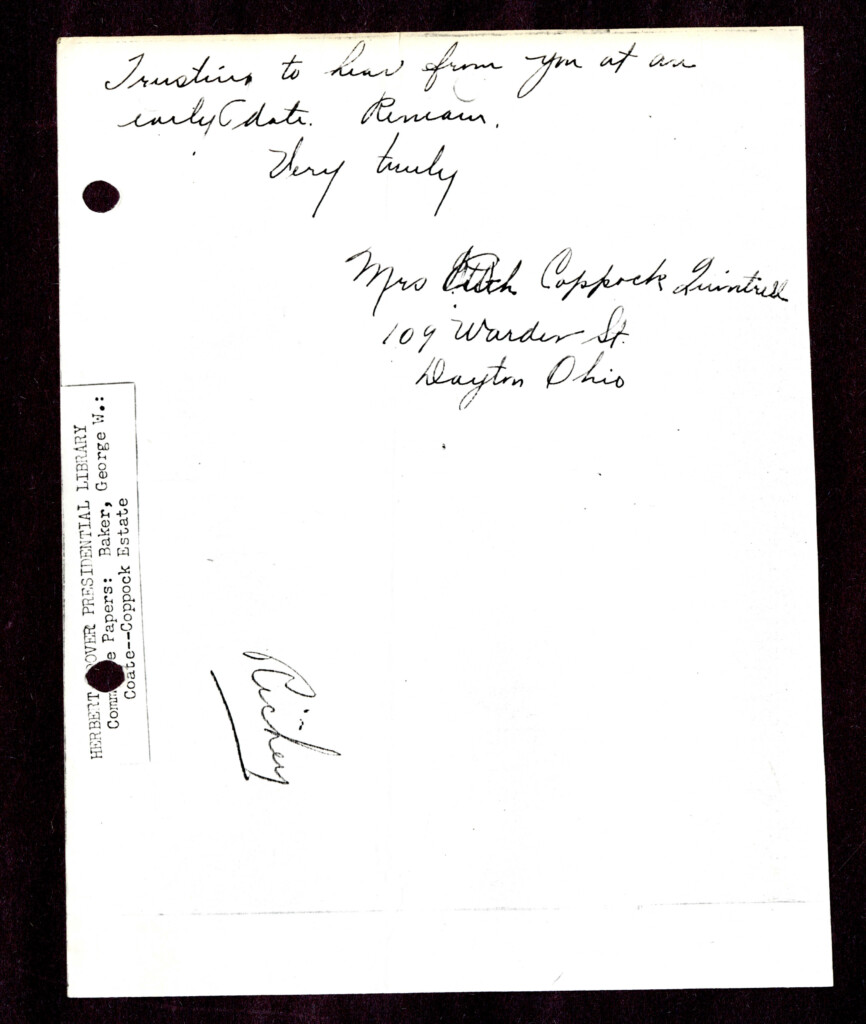

Photocopies of correspondence between Ruth Quintrell and Herbert Hoover from the Herbert Hoover Presidential Library

Photocopies of correspondence between Ruth Quintrell and Herbert Hoover from the Herbert Hoover Presidential Library

Photocopies of correspondence between Ruth Quintrell and Herbert Hoover from the Herbert Hoover Presidential Library

Photocopies of correspondence between Ruth Quintrell and Herbert Hoover from the Herbert Hoover Presidential Library

Photocopies of correspondence between Ruth Quintrell and Herbert Hoover from the Herbert Hoover Presidential Library

In the end, Carpenter found that the Federal Government had decided against prosecuting Amanda Krell and Glen B. Coate. Instead, they issued a permanent injunction which was why finding records about the case proved to be difficult. In his book “Wenderoth Families of Germany,” Carpenter spends 21 pages going through the documents he found while researching the case.

Scams like this still happen today. They are usually better known as the “Nigerian prince” scam.

Blog written by Sarah Pfundstein, genealogy librarian, Indiana State Library. For more information, contact the Indiana State Library at 317-232-3689 or “Ask-A-Librarian.”