“So, what is the Indiana State library?” As the communications director at the State Library, this is a question I often hear at conferences immediately after the person who asked the question realizes that we’re not the Indianapolis Public Library. It’s a fair mistake. After all, not many cities are privileged enough to have two large downtown libraries. More importantly, though, it’s a great question. What do we do here at the Indiana State Library? Predictably, the answer to that question is “a lot.” All libraries do a lot. However, the Indiana State library functions a little bit differently than a public or academic library.

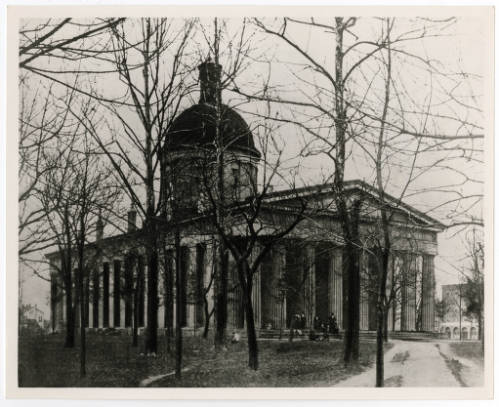

The Indiana State Library from W. Ohio St.

For starters, the Indiana State Library is a state government agency. Yes, we are all government employees of the State of Indiana, which is why we all have cool badges with our pictures on them. As a state agency, the library operates using a two-pronged approach. One prong is public services, the side of the library which, as the name implies, serves the citizens of Indiana and preserves the state’s history. The other prong is statewide services, the side of the state library which supports libraries throughout the state. Our mission statement sums up these two operational divisions: “Serving Indiana residents, leading and supporting the library community and preserving Indiana history.”

The Indiana State Library from Senate Ave.

Public Services

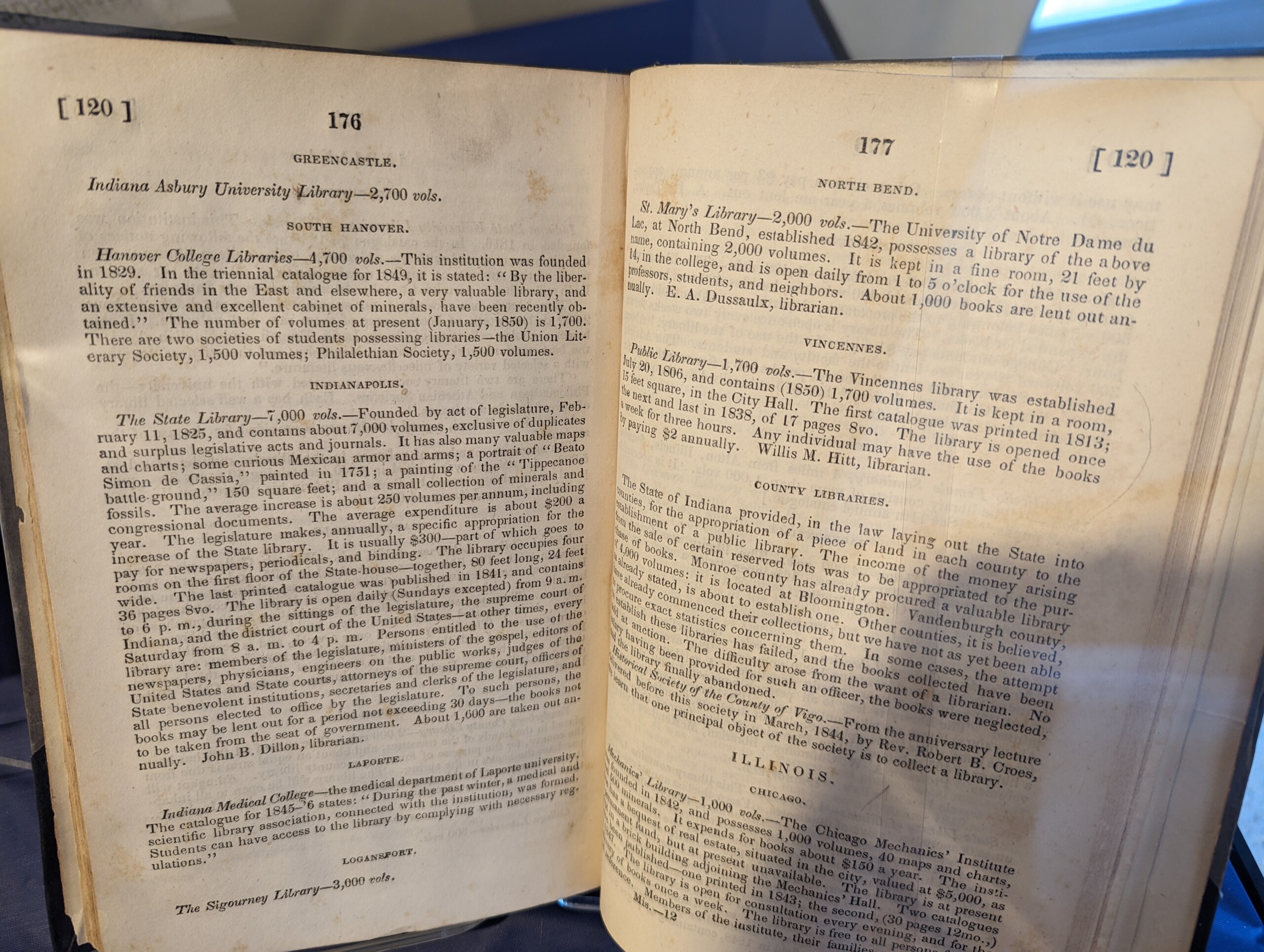

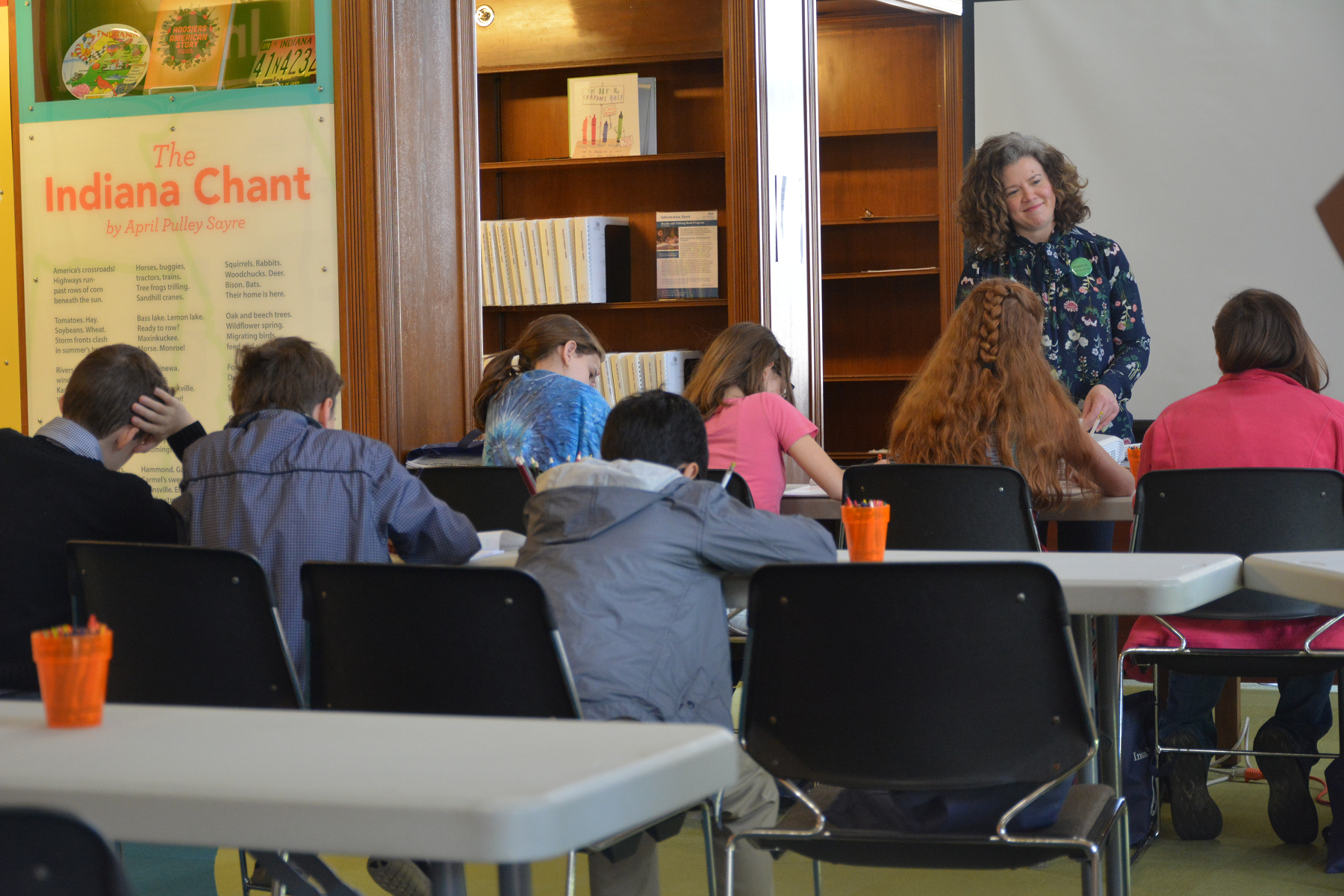

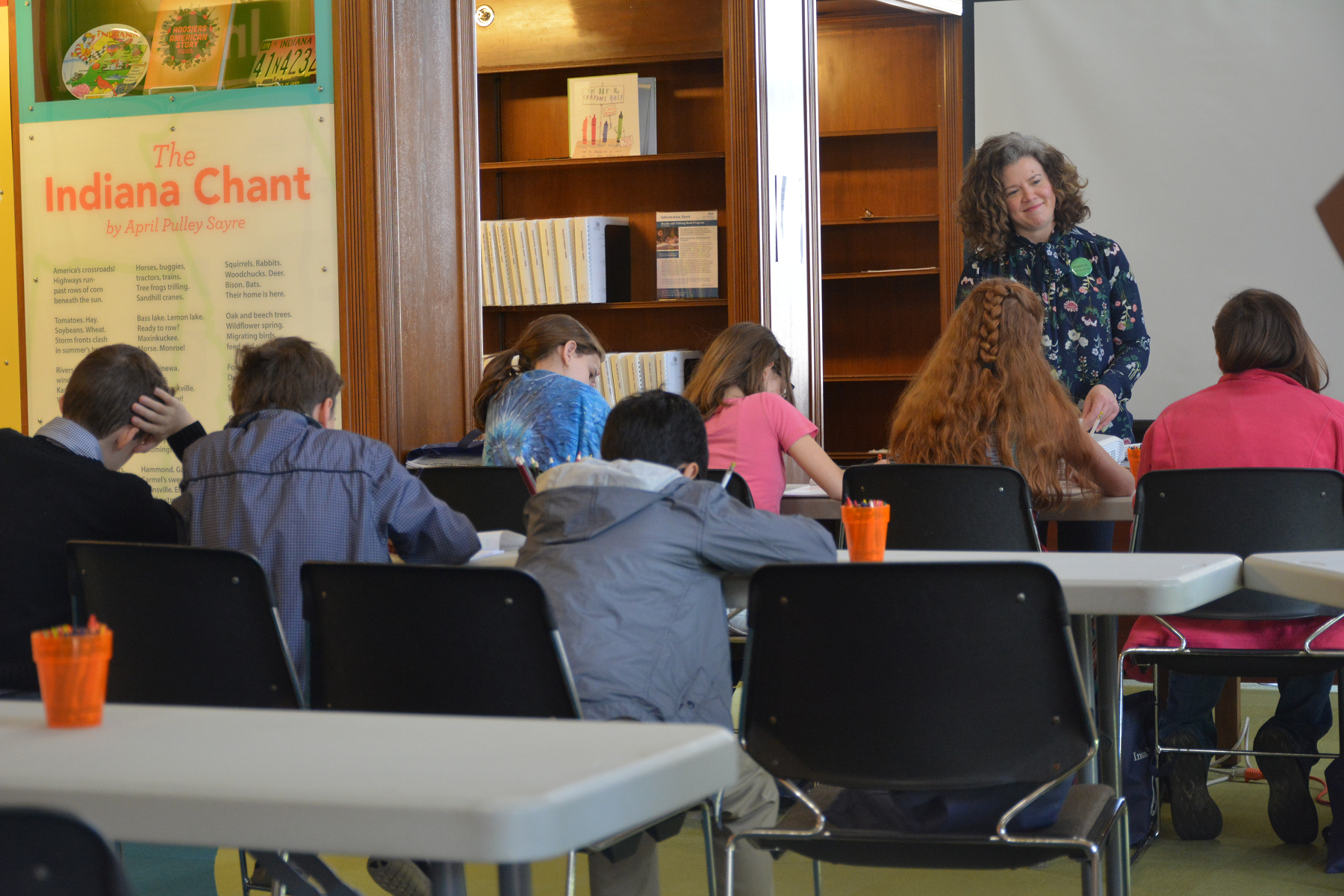

On the public services side, we operate in a similar fashion to a public library. A special research library, the Indiana State Library is a beautiful Art Deco building, opened in 1934, that sits on the Canal Walk in downtown Indianapolis near the Indiana Historical Society, the Eiteljorg Museum and the Indiana State Museum. Two of the library’s four floors are open to the public. However, we differ from a traditional public library in that the majority of our materials are Indiana-related. We do not carry many of the latest popular fiction and nonfiction titles – unless they are Indiana-related – but we do have the largest collection of Indiana newspapers in the world. In the state, our genealogy collection is second to only the Allen County Public Library in terms of size, and our collection is one of the largest in the entire Midwest. We also house the Indiana Young Readers Center, the only young readers center within a state library in the country. The center is modeled after the Library of Congress Young Readers Center and features Indiana authors and illustrators, including Jim Davis, Meg Cabot, Norman Bridwell and John Green. The state’s Talking Book and Braille Library is also part of the Indiana State Library. TBBL provides free library service to residents of Indiana who cannot use standard printed materials due to a visual or physical disability. TBBL also operates Indiana Voices and hosts the biennial Indiana Vision Expo.

Letters About Literature workshop in the Indiana Young Readers Center

On the subject of events, in addition to Vision Expo, the state library also hosts the annual Indiana Poetry Out Loud finals, Letters About Literature, the Genealogy Fair and Statehood Day. Furthermore, the library offers INvestigate + Explore summer programming for children; Genealogy for Night Owls; monthly one-on-one DNA testing consultations with the Central Indiana DNA Interest Group; various history and genealogy lectures and programs, highlighted by our recent lecture series; and even the occasional art opening in our Exhibit Hall. Yes, we even showcase fine art when our many display cases throughout the library aren’t already put to use featuring some of the wonderful items in our collection – which are often featured in this blog.

Dolls created by the Work Projects Administration in 1939 for the Indiana Deaf History Museum on display as part of the “Welcome to the Museum!” exhibit in the library’s Exhibit Hall.

Wait, there’s more! The Indiana State Library is a DPLA hub via Indiana Memory, a collection of digitized books, manuscripts, photographs, newspapers, maps and other media. Indiana Memory is a collaborative effort between Indiana libraries, archives, museums and other cultural institutions. The library also maintains its own digital collection, covering a wide range of topics such as the arts, environment, sports and women.

We participate in the Federal Depository Library Program and serve as the congressionally-designated regional depository of Indiana. As the regional depository, the library is required to collect all content published by the U.S. government. The library is also the home of the Indiana State Data Center. State data centers across the country assist the Census Bureau by disseminating census and other federal statistics. The data center provides data and training services to all sectors of the community including government agencies, businesses, academia, nonprofit organizations and private citizens.

The Indiana Center for the Book is a program of the Indiana State Library and an affiliate of the Center for the Book in the Library of Congress. The center promotes interest in reading, writing, literacy, libraries and Indiana’s literary heritage by sponsoring events and serving as an information resource at the state and local level.

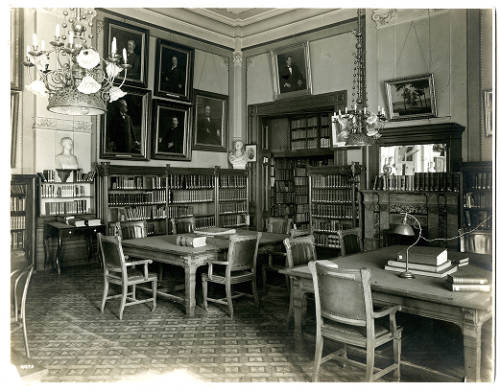

The Martha E. Wright Conservation Lab

The Martha E. Wright Conservation Lab is the center for all things preservation and conservation at the Indiana State Library. Preservation and conservation services aims to improve and ensure long-term, ongoing access to the cultural and historical collections of the Indiana State Library. The department, staffed by one full-time conservator as well as volunteers and occasional interns, fulfills this primary goal by providing conservation treatments of collections items and implementing preventive care and administrative policies.

Finally, our Ask-a-Librarian service offers an opportunity for anyone to, well, ask a librarian a reference or research question. Questions may be submitted 24/7 to Ask-a-Librarian and all questions will be answered within two business days.

All of these services come courtesy of our divisions: Genealogy, Indiana, Rare Books and Manuscripts, Catalog, Talking Books and Braille and Reference and Government Services.

Pretty simple, right? Shall we move on to statewide services?

Statewide Services

Nearly every single library patron in the state of Indiana has benefited from the Indiana State Library’s statewide services. While some programs and services are offered directly to Indiana residents, the vast majority of statewide services could be considered behind-the-scenes. Not many patrons ponder how their interlibrary loans travel from one location to another or how librarians keep up with their required continuing education, but statewide services makes them possible. Statewide services consists of two divisions, the Library Development Office and the Professional Development Office, or LDO and PDO, as they are known to many library employees throughout the state.

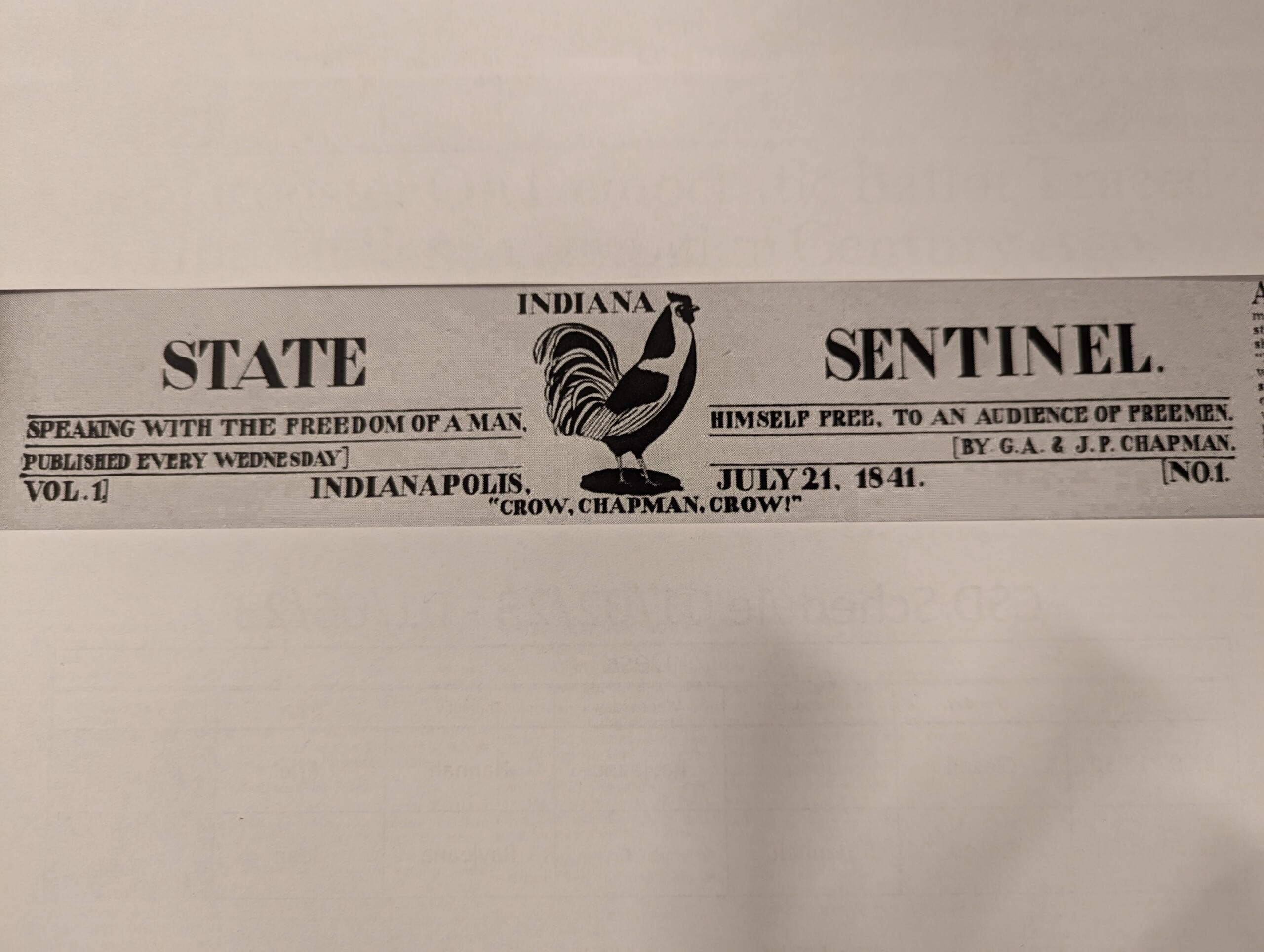

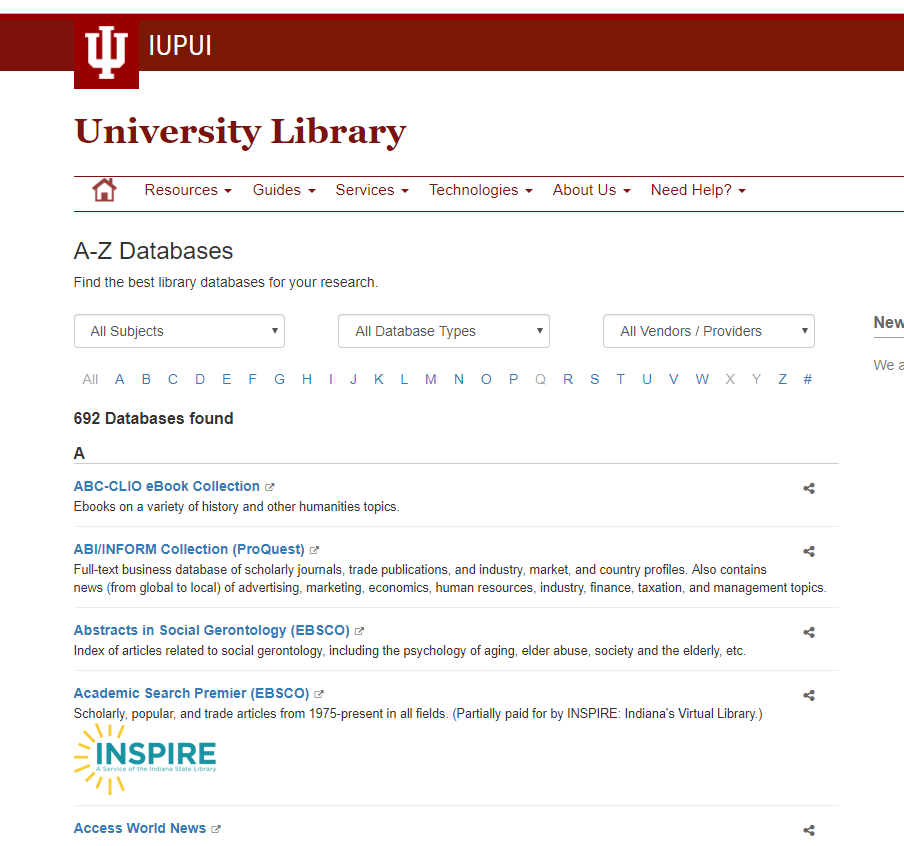

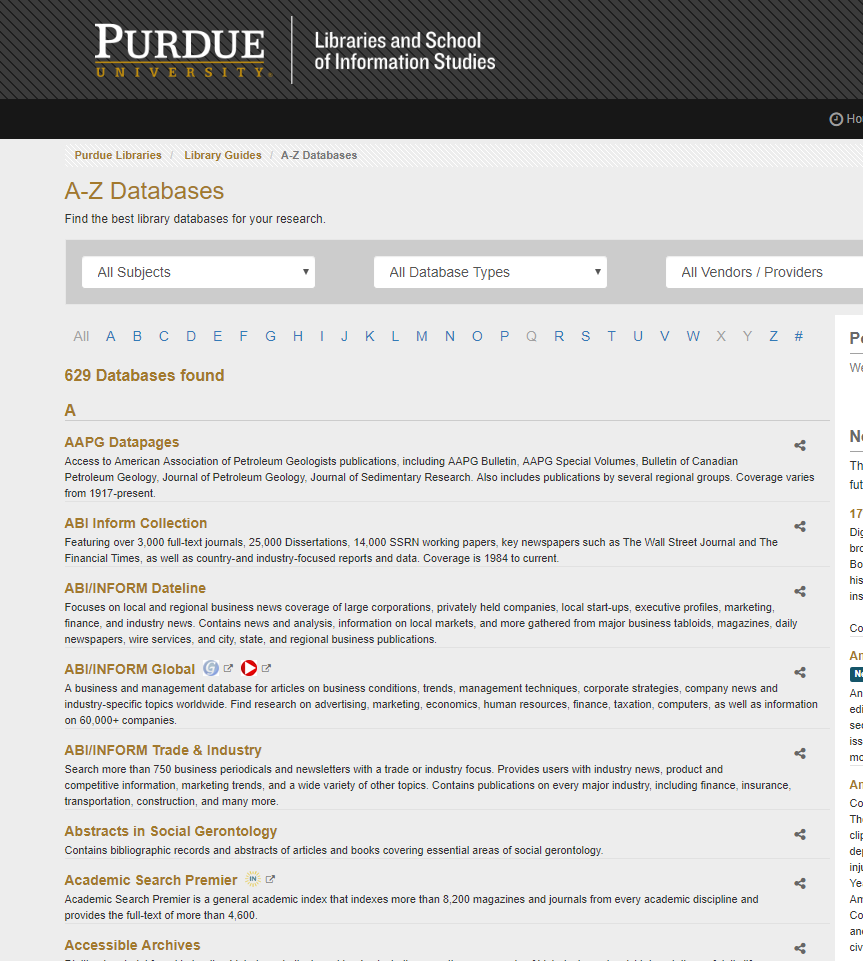

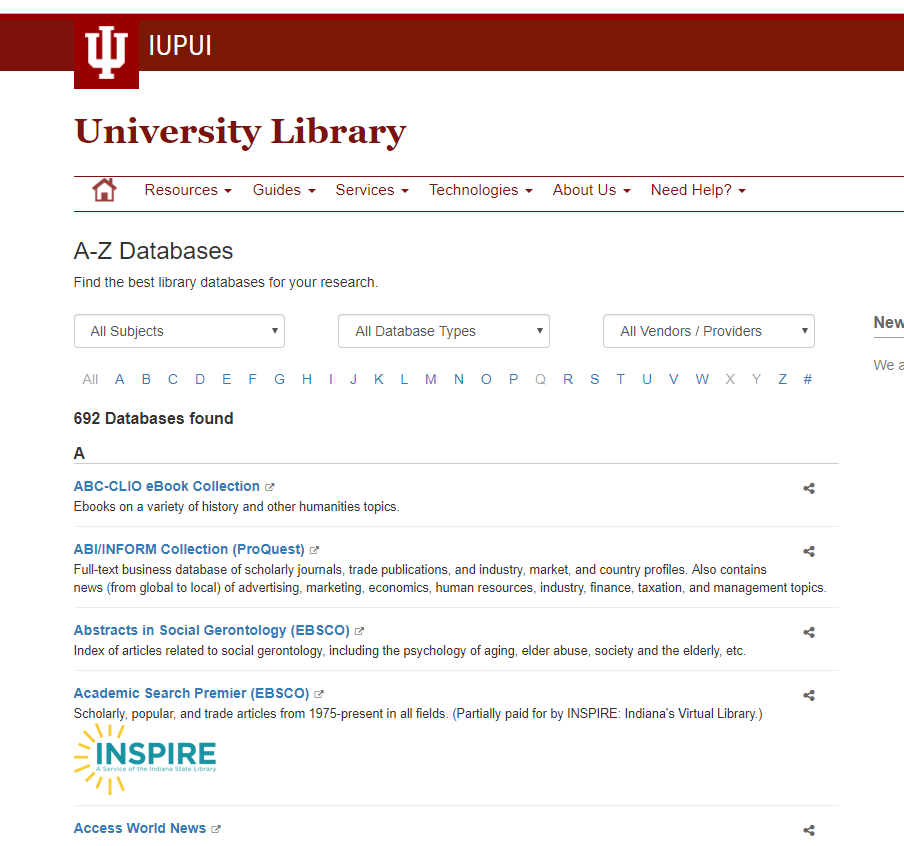

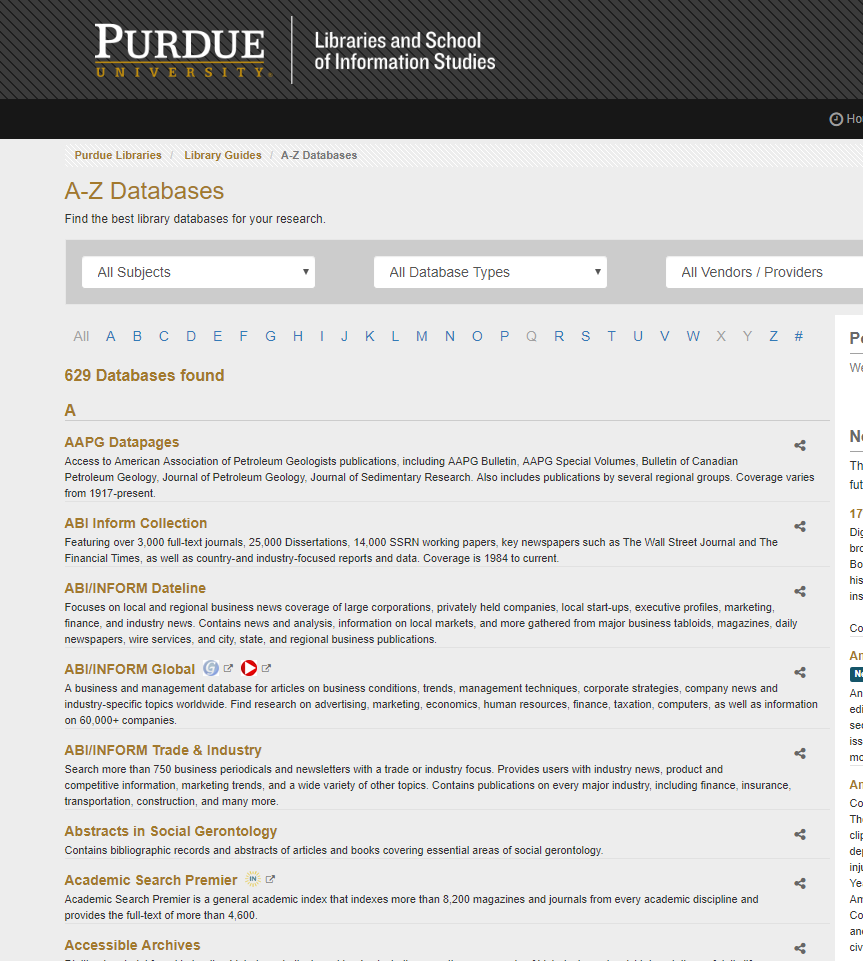

LDO supports the improvement and development of library services to all Indiana citizens. The aforementioned Indiana Memory, Hoosier State Chronicles – which is Indiana’s digital historic newspaper program with nearly a million digitized Indiana newspaper pages – and INSPIRE are three programs freely available to Indiana residents that are maintained by LDO.

Hey, that’s us!

INSPIRE, also known as “Indiana’s virtual library,” is a collection of vetted databases provided to the residents of the state at no cost. INSPIRE offers a diverse collection of reference materials, such as free access to level one of Rosetta Stone in 30 languages, a small business resource database, the latest issues of Consumer Reports and much more. If you attended high school or college in Indiana in the last 20 years and needed online resources, there’s a good chance you’ve used INSPIRE.

Hey, that’s us, too!

Let’s get to the behind-the-scenes stuff from LDO. The Library Development Office administers over $3 million of LSTA grant money each year. This federal funding, distributed from the Institute of Museum and Library Services as part of the Grants to States program, is intended for projects that support the Library Services and Technology Act signed into law Sept. 30, 1996. The purposes and priorities of the LSTA include increasing the use of technology in libraries, fostering better resource sharing among libraries, and targeting library services to special populations. While the Indiana State Library does set aside an allotment to be awarded directly to libraries as competitive LSTA sub-grants, the majority of the funds are funneled into services meant to benefit the entire state.

Remember those interlibrary loans? Well, they travel from library to library via a combination of SRCS, Indiana Share and InfoExpress. SRCS, Indiana’s Statewide Remote Circulation Service, links together catalogs of over 150 libraries containing over 30 million items. These materials are delivered to your library using the InfoExpress courier service. Indiana Share also allows libraries to request interlibrary materials though the Indiana State Library.

In addition to LSTA-supported programs, LDO supports E-rate, the discount telecommunication program available to schools and libraries from the federal government; the PLAC card program, which allows an individual to purchase a Public Library Access Card, thus permitting them to borrow materials directly from any public library in Indiana; and Read-to-Me, a cooperative effort between LDO and the state’s correctional facility libraries to enable incarcerated parents an opportunity to share the joys of reading with their children.

The complete list of services provided by the Indiana State Library and administered by LDO are far too expansive to cover in a single blog post, but I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention that LDO also provides consultation to libraries across the state in the areas of library finance, management, planning, evaluation, grants, board training, trustees, expansion, library standards, certification, statistics, new director information and unserved communities.

PDO supports the advancement and development of library staff in all Indiana libraries for improved services to the citizens of Indiana. The Professional Development Office includes specialists in the areas of programming, children’s services and continuing education. The four regional coordinators and the children’s consultant travel the state to provide support for library employees in Indiana.

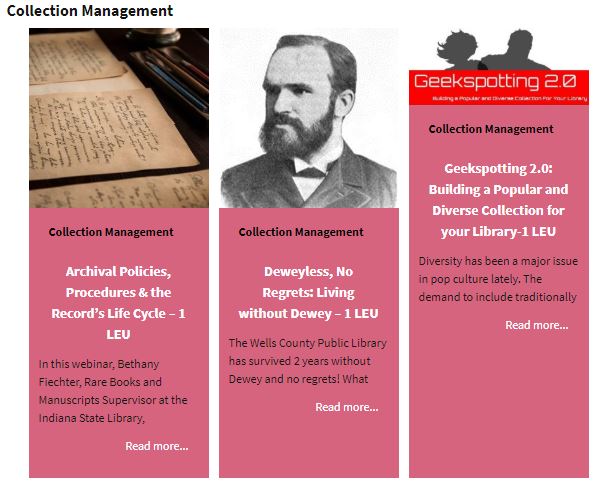

Staff working at Indiana public libraries who spend at least 50% of their time on professional library work are required by law to be certified; they gain and maintain certification by earning a certain amount of library education units, also known as LEUs, every five years. PDO frequently oversees, creates or produces these webinars, which cover a wide range of topics. “So, You Want to Start a Library Podcast,” “Serving Adults with Disabilities” and “Teaching iPad and iPhone to Seniors” are just as few examples of recent webinars. Additionally, PDO assists librarians in locating other sources of continuing education outside of the state.

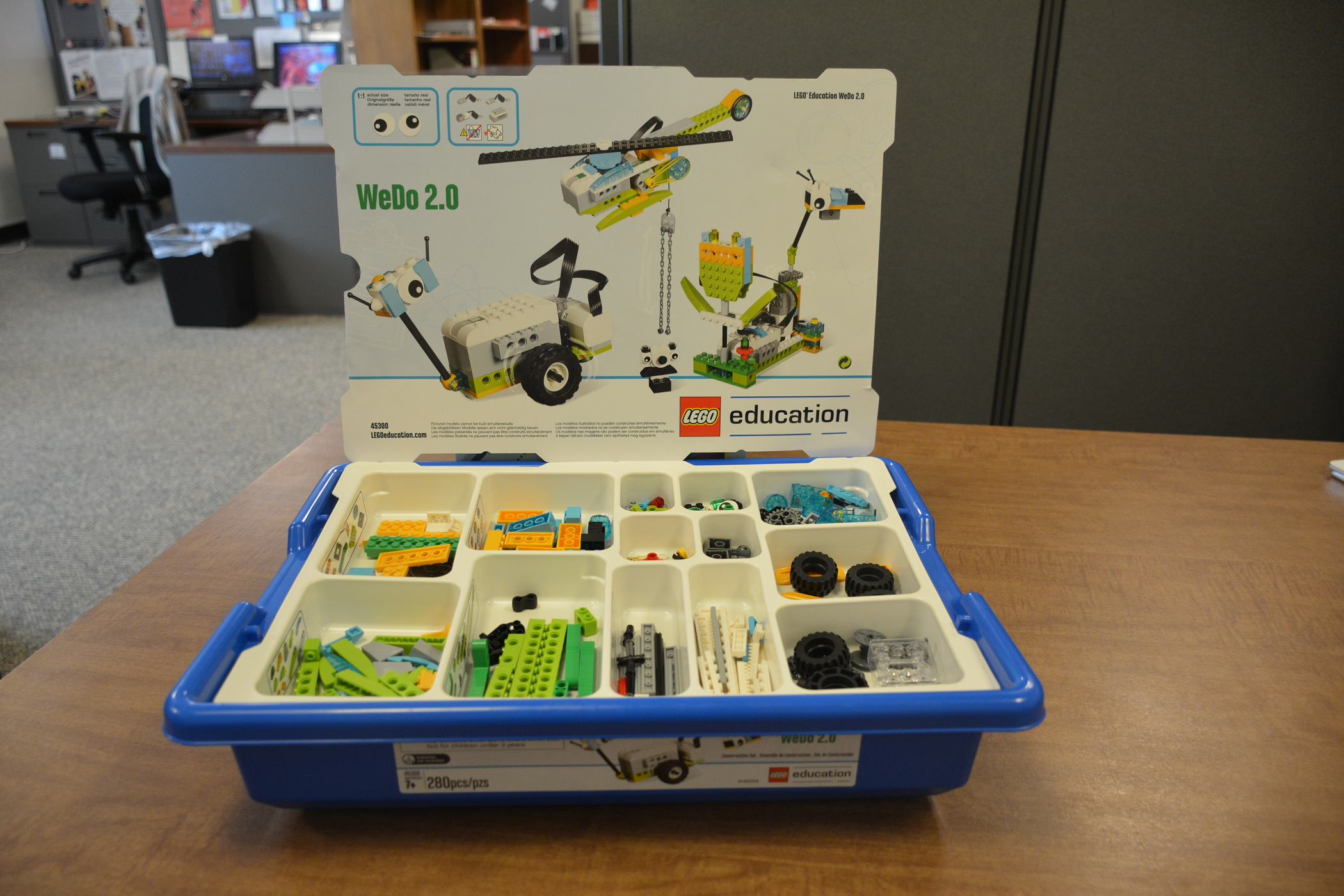

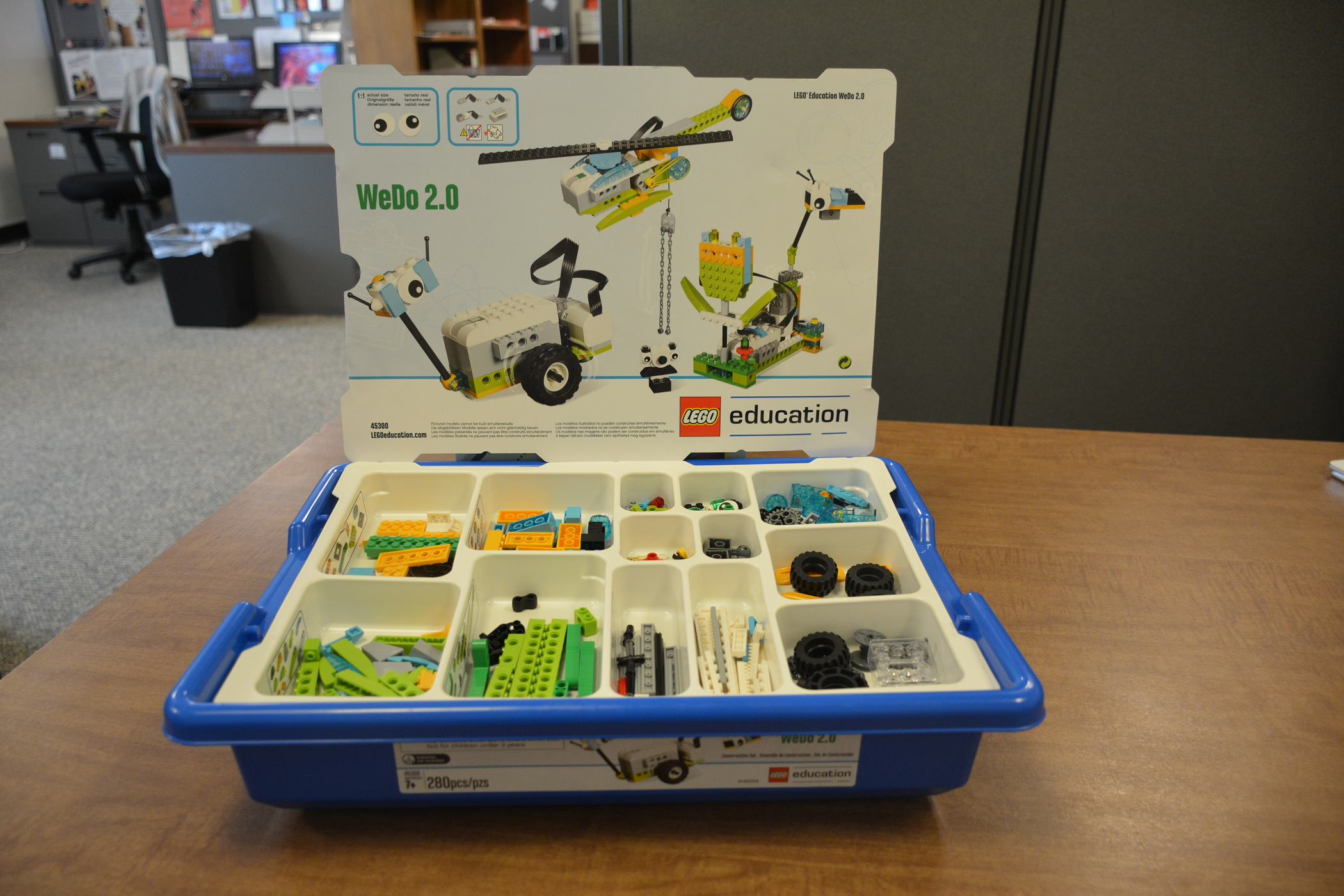

Legos!

The Professional Development Office provides five types of kits for use by youth librarians across the state: book club kits, LEGO kits, DUPLO kits, storytime kits and Big Idea storytime kits. PDO also maintains the wildly-popular VR kits. The kits are shipped to schools and libraries via InfoExpress and may be kept for a specified duration of time.

Connect IN, the program that provides free high-quality and functional websites to public libraries without a current online presence, and to those having difficulty maintaining their existing site, is managed by PDO. Connect IN provides a modern and high-quality website, tech support and training, content management system training, free website hosting and free email for library staff.

The 2019 The Difference is You conference

In addition to the daily consultation and educational support offered by PDO staffers, the department spearheads larger initiatives throughout the year to honor and develop current library employees. These initiatives include the Indiana Library Leadership Academy and the The Difference is You library support staff and paraprofessional conference. Whether it’s working with individual librarians or entire gatherings, PDO puts the continuing education of Indiana librarians at the forefront of all they do.

Does your local library use the Evergreen catalog? That’s also a service provided to more than 100 Indiana libraries from the Indiana State Library that falls under the statewide services banner. Evergreen is funded by the Indiana State Library through LSTA monies and participant membership fees. The services provided by the State Library include purchasing and maintaining the central servers, personnel costs in operating the system, training, software development, data conversion and other related expenses.

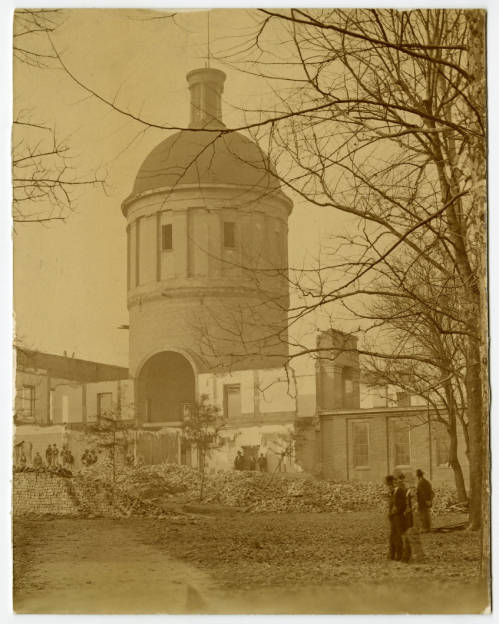

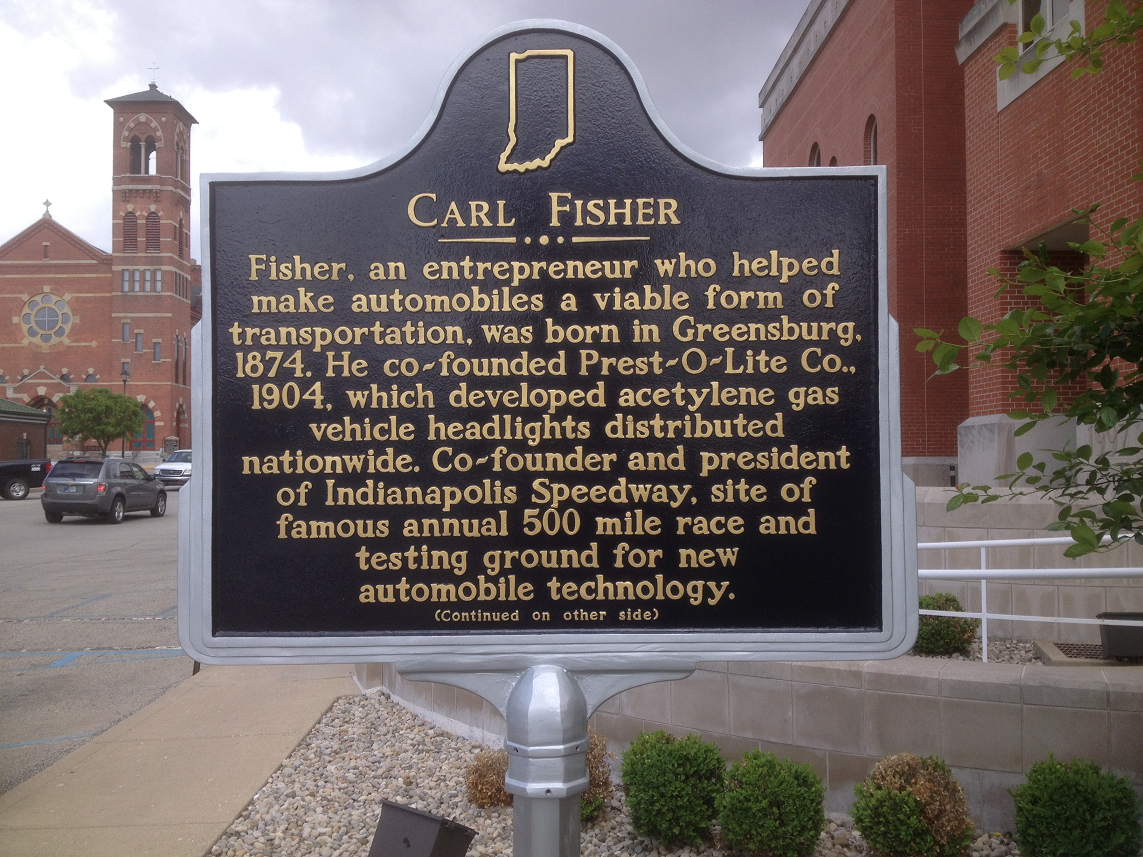

The Indiana Historical Bureau and the Statehouse Education Center

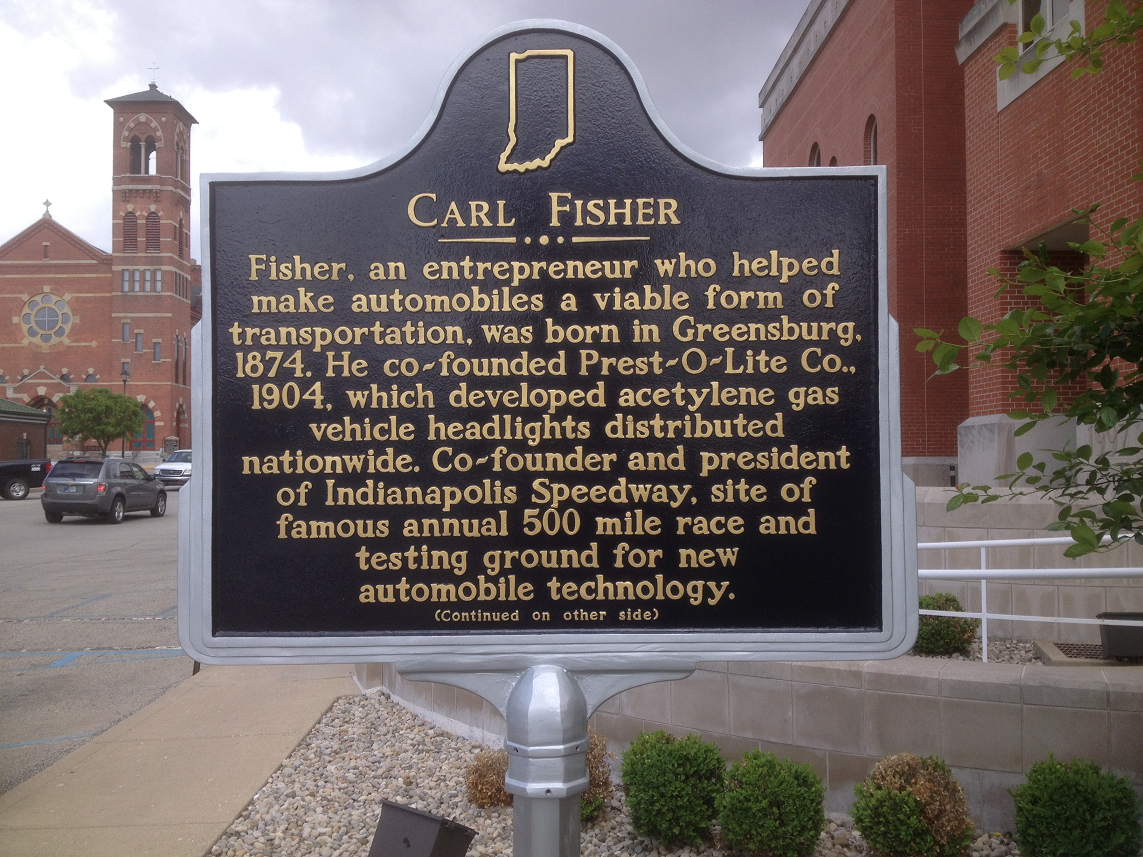

The Indiana State Library has within its walls the Indiana Historical Bureau and the Statehouse Education Center. In 2018, the Indiana Historical Bureau, previously its own agency, merged with the Indiana State Library. The historical markers you might see while travelling the state are part of the Indiana Historical Marker Program administered by the bureau. Additionally, the Indiana Historical Bureau regularly publishes a detailed history blog, digitizes many historical items, organizes the Hoosier Women at Work conference and produces the award-winning podcast Talking Hoosier History. In 2017, the 120th Indiana General Assembly passed HB1100 mandating that the Indiana Historical Bureau “establish and maintain an oral history of the general assembly,” leading to the Indiana Legislative Oral History Initiative.

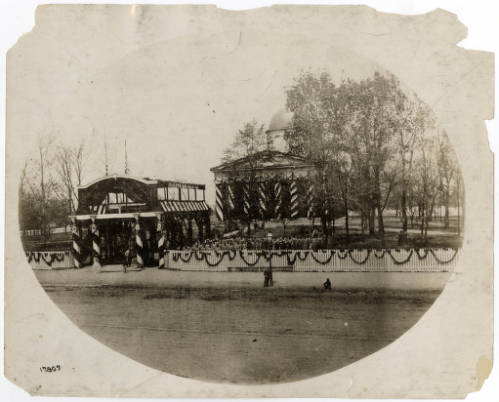

Courtesy of the Indiana Historical Bureau

The Statehouse Education Center is a project of the Indiana Bicentennial Commission, a commission that was assembled to spearhead the strategic plan behind the celebration of Indiana’s 2016 bicentennial. As part of the Statehouse Tour Office under the Indiana Department of Administration, the center sees thousands of students, families and individuals each year who learn how state government works for them through interactive exhibits on voting, urban versus rural landscapes and the architecture of the statehouse.

Thank You

Hopefully, I’ve given you a sense of the many services the Indiana State Library provides publicly and behind the scenes. Everything the library does would not be possible without our many volunteers and employees, the Indiana Library and Historical Board, the Indiana State Library Foundation, the General Assembly, our financial office and the work of our many committees, including the INSPIRE Advisory Committee, the IMDPLA Committee and the Resource Sharing Committee… just to name a few. Indeed, we all do “a lot.”

This blog post was written by John Wekluk, communications director, Indiana State Library. For more information, email the communications director.