Have you ever stumbled upon a stack of old family photographs and found yourself fascinated by informal snapshots and formal portraits taken decades before you were born? Your eyes take in their outmoded dress and staged poses and scan their faces looking for a flicker of recognition and find none. You wonder who they were, flip over the images and learn, much to your dismay, that the back is blank. After a moment’s disappointment, you decide you’re going to rectify your ancestors’ oversight and find out who these nameless people were, even if you’re a little fuzzy on the how.

As an archivist, I work with a lot of family photograph collections. If I’m very fortunate, some enterprising relation took the time to label a good portion of the photographs with names, dates and even locations. Most of the time, I’m not that lucky.

So, where do you start when you can’t identify most of the people in your photographs? Just keep reading. I’ll walk you through my process for researching and caring for enigmatic family photographs with examples from the recently processed Lucile Johnson photograph collection.

1. Rage at the skies

Quickly move through the stages of grief.

- Denial: No way an entire box of photographs only has seven identified photos!

- Anger: I can’t believe no one thought to get more information from the owner when they were alive!

- Bargaining: “Hey, Bob. You like unnecessarily complicated puzzles and hate cleaning the breakroom. I’ll trade you! No?”

- Depression: Stare at photos hopelessly for 10 minutes. Maybe shed one lonely tear.

- Acceptance: After you’ve sufficiently lamented, accept your fate. You’re doing this thing.

2. Get to know the family

2. Get to know the family

“The King and I” (1956); 20th Century Fox; Tenor

I was fortunate when it came to the Lucile Johnson photo collection because a previous staff member had already assembled a brief bio for Lucile – also spelled Lucille – so I knew she was born in Vincennes, Indiana in 1908 and her mother’s name was Bertha Johnson. She also worked at Wasson’s department store in Indianapolis. While I generally give my predecessors the benefit of the doubt, I always try to verify such facts, especially when they don’t include sources, because people make mistakes. It’s a fact of life. Regardless, surveying the photographs before taking a deep dive into a family history is good practice.

Lucile Johnson working Coty counter at H.P. Wasson’s, 1946; Indiana State Library

Flip through the photos

Keep in mind who, what, when and where as you do this. Are you noticing the same faces or places over and over again? Do certain people appear together in multiple photographs and do they look like family (e.g., multiple generations, similar facial features, etc.)?

Make an effort to keep the photos in original order – it could be important

Someone may have had a very good reason for organizing them the way you found them. Or someone could have just tossed them in a box. Either way, you should pay attention to it and decide whether you should retain that order or reorganize the photographs later.

Gather low-hanging fruit first

Handwritten notes or printed information may be even more important if they’re scarce. Many older photographs such as cartes de visite and cabinet cards have information about the photographer printed on the fronts or backs, often including the location of the studio. A handwritten caption noting an event or a person’s name on one photograph could be the key to identify several images in a series.

In the Johnson photo collection, the only consistent notations I found were estimated dates in square brackets a previous librarian must have assigned in pencil. Square brackets are often used to denote information added by archivists to differentiate them from notes written by creators or owners.

3. Form connections

“Sherlock,” BBC; Hartswood Films; Kansas City Public Library

When I’m trying to connect the dots, I look for obvious relationships and repeating clothing and backgrounds. If you’ve elected to reorganize your photographs, you can begin by physically grouping the photographs based on event, place, time period, format or another factor that makes sense to you.

Find familiar faces

Identify commonalities. If you have recognized the subjects in one or two photographs, search for them throughout the images. Make note of dates, locations, their companions and events.

Right away, while looking through Lucile’s photographs, I could see that many of the snapshots were part of a series taken together based on the people, clothing, places and/or time period. A photograph identifying a man named J. H. Moyer, allowed me to pick him out in several other photographs and later, make educated guesses as to his companions.

Left: J.H. Moyer (green) walking street, 1941; right: J.H. Moyer with group, including Lucile, (yellow); Indiana State Library

Pay attention to notable places

Based on several snapshots, Lucile and a group of friends seemingly went on holiday together when they were young ladies. For many Hoosiers, the round building in the background is instantly recognizable as the iconic West Baden Springs Hotel in Orange County. Your own familiarity with common landmarks, legible signage or even a Google reverse image search can all lead you to successfully identifying places in your photographs.

Lucile (yellow) with five friends at West Baden Springs Hotel, ca. 1922; Indiana State Library

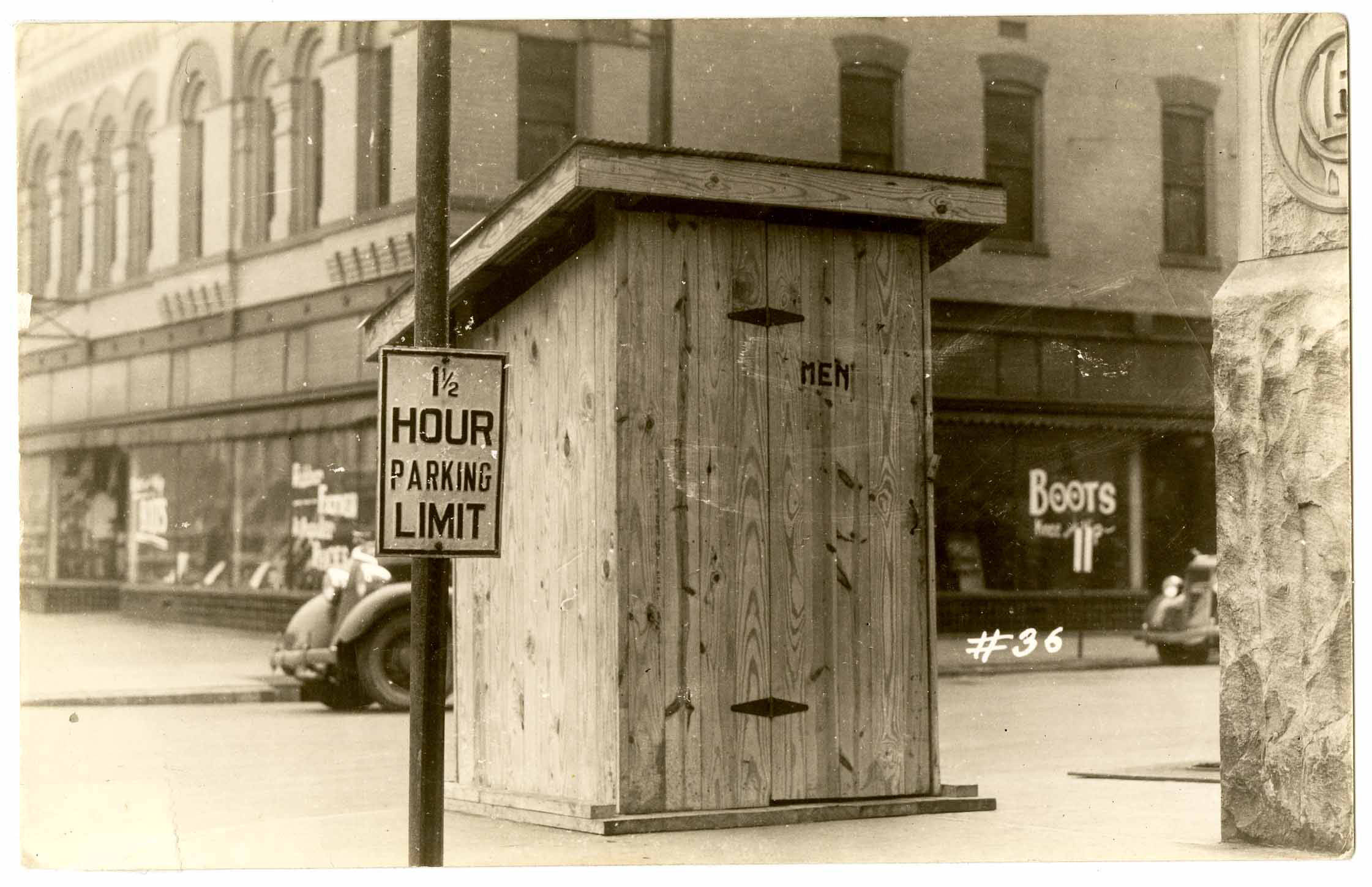

Date the images

You can narrow down or even pinpoint when a photo was taken by observing details such as fashion, architecture, insignia, signs, photo formats and more. This blog post from the National Archives walks you through the process step-by-step.

Draw a family tree

If you’re faced with a convoluted family or you’re a visual person, creating a family tree is a must. It doesn’t have to be fancy, but I do recommend using a pencil with an eraser if you’re doing it by hand because you’re going to make mistakes. You can also find family tree templates to print out or take advantage of online tools or software. Unless you have an eidetic memory like Barbara Gordon, notes and family trees may be crucial for the next step.

4. Investigate

Search genealogy databases

Search genealogy databases

Once you have a person’s name and a few other details – an approximate birth or death date, a place they may have lived, a close family member – you can start online sleuthing. Genealogy databases, newspapers, digital collections and cemetery projects are the bread and butter of this research. If you don’t want to spring for subscription databases, which is legit, start by searching free databases like FamilySearch and Find A Grave to find your person and identify their social bubble.

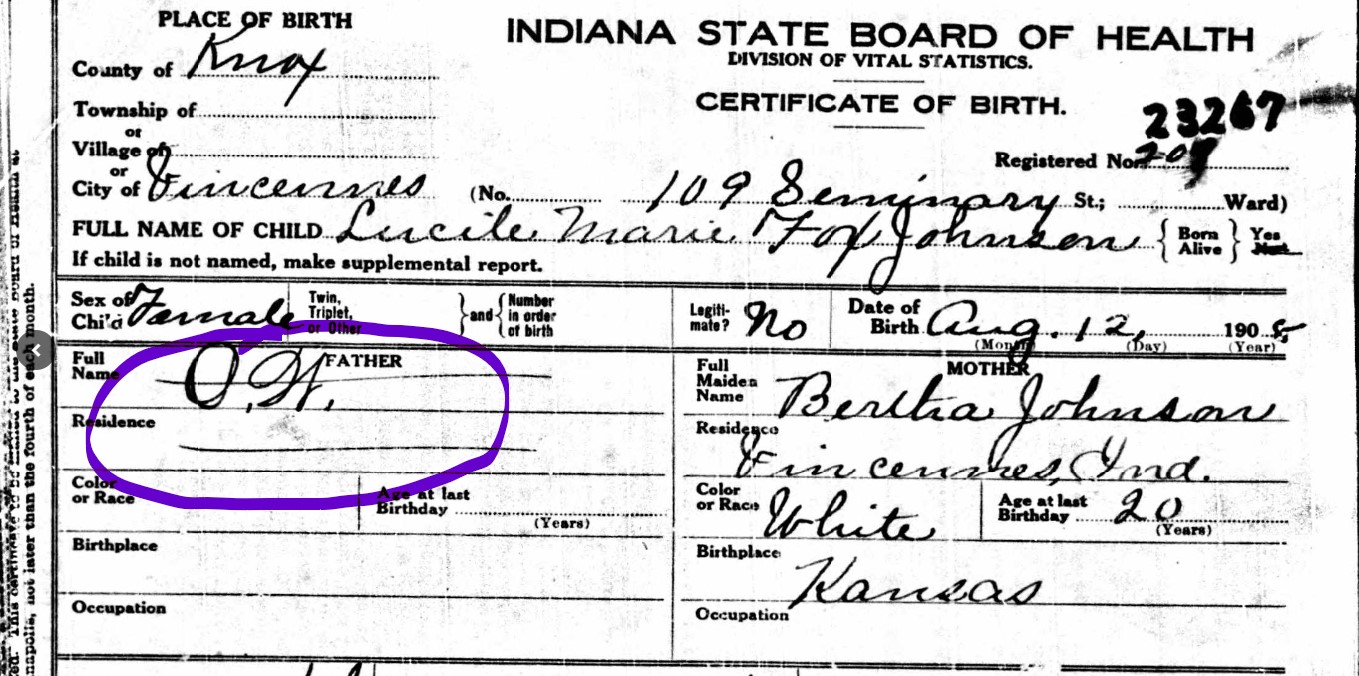

While researching Lucile Johnson and her mother, Bertha, I easily located birth and early census records and discovered a mystery. At first glance, the birth certificate was just like any other, informing me Lucile Marie Fox Johnson was born in Vincennes, in Knox County, Indiana on Aug. 12, 1908. Her mother’s name was listed as Bertha L. Johnson and her father’s name was listed as O.W. Wait, what?

Now, I’m a manuscripts librarian, which is just another term for archivist, so only a small fraction of my job is doing genealogical research, unlike our dedicated and talented genealogy librarians. I must confess I had to Google the acronym to figure it out. If you, like me, have never encountered this before, O.W. on an old birth record means “out of wedlock.” And that’s when I knew this research was going to get a lot more interesting. A baby born to an unmarried young woman in a small town in the Heartland in the early 20th century? There’s a story there. I just had to hope I could find the records to tell it.

The question became, how do I discover the identity of Lucile’s father when his name doesn’t appear in most typical records? One possible clue came from Lucile’s own name – Lucile Marie Fox Johnson. A middle name of Fox in the early 1900s was less likely to be a parent’s attempt at whimsy or an indication of their love of vulpine creatures and far more likely to be a surname, usually familial. It seems important to note that a surname as a middle name was often the maiden name of the mother, when a child’s parents were married. In Lucile’s case, it could indicate a pointed statement from her mother to ensure the world knew, as the people in Knox County surely did, who her father was. Keep this in mind, as we’ll come back to it.

The question became, how do I discover the identity of Lucile’s father when his name doesn’t appear in most typical records? One possible clue came from Lucile’s own name – Lucile Marie Fox Johnson. A middle name of Fox in the early 1900s was less likely to be a parent’s attempt at whimsy or an indication of their love of vulpine creatures and far more likely to be a surname, usually familial. It seems important to note that a surname as a middle name was often the maiden name of the mother, when a child’s parents were married. In Lucile’s case, it could indicate a pointed statement from her mother to ensure the world knew, as the people in Knox County surely did, who her father was. Keep this in mind, as we’ll come back to it.

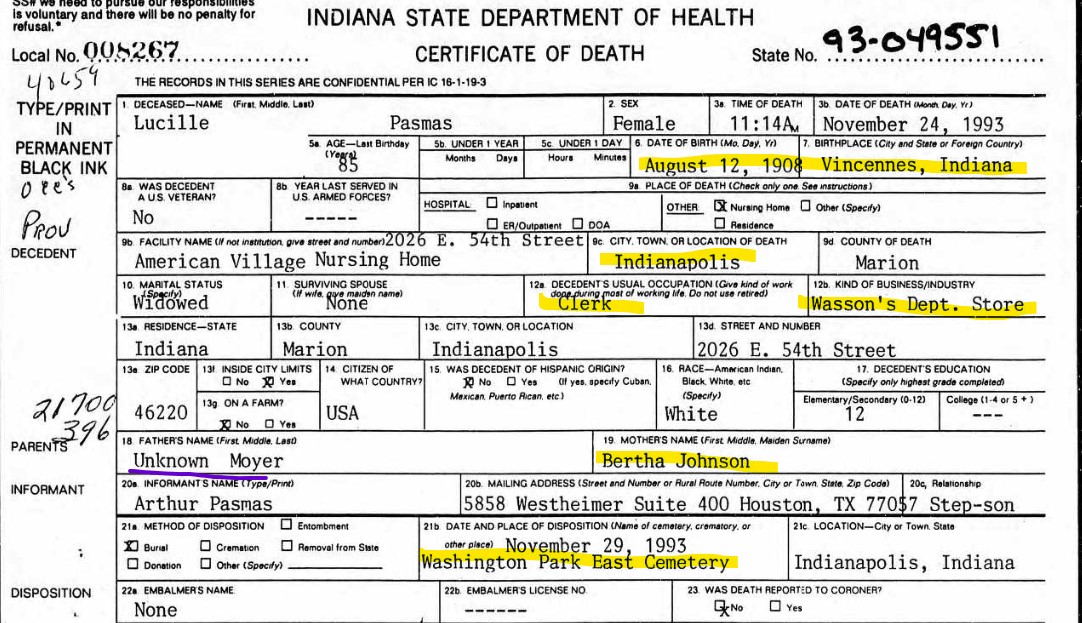

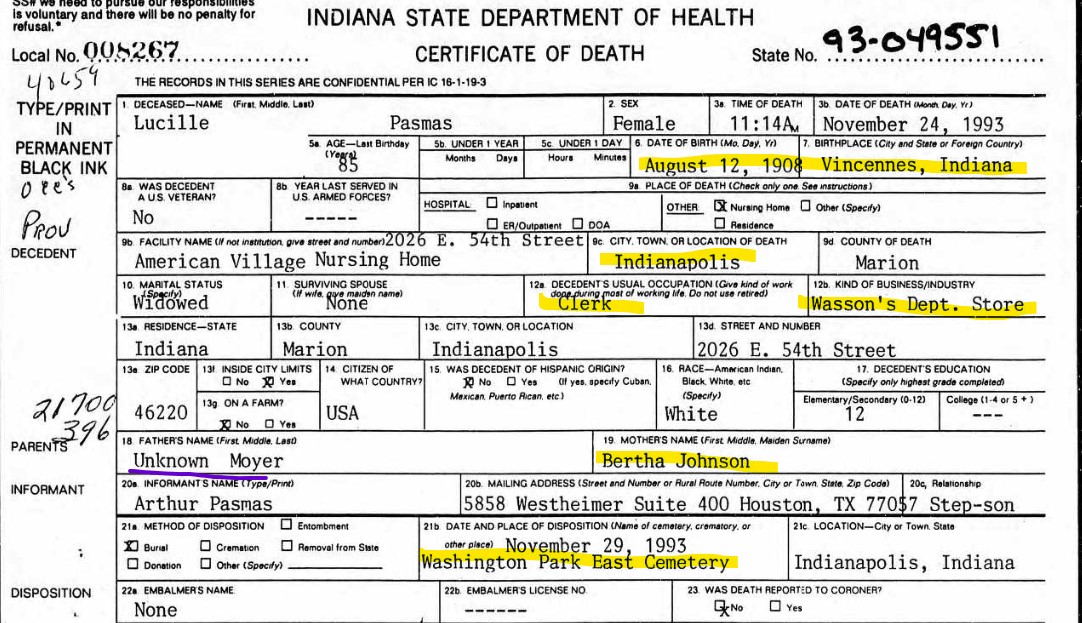

While continuing to gather more information on Lucile M. Johnson, I also came across Lucile Moyer Pasmas’ death certificate and gravestone. In the photo collection, there are a few photographs of people identified as Moyers, so I looked closer. The birthdate, birthplace, mother’s name, profession, and place of residence – Indianapolis – on the certificate match Lucile M. Johnson. What caught my attention was the father line, which listed Unknown Moyer. It lines up with the O.W. on her birth certificate, which made me certain I had found the right Lucile. However, her father was a Moyer? I supposed it could be true. I did have those photographs, but then what was the origin of Fox on her birth certificate? And if her father wasn’t a Moyer, Lucile may have married one instead.

Lucille (Johnson) Moyer Pasmas death certificate, 1993; ancestry.com

Crowdsource and consult the experts

About this time, I enlisted the aid of the library’s incomparable genealogy supervisor, Jamie Dunn, to help me locate marriage records for Lucile’s presumed first marriage to Ford D. Moyer. I’m not going to get into that saga here, but you can view the results in the collection finding aid’s biographical note. Jamie didn’t locate the elusive marriage record I hoped to find, but she did discover the identity of Lucile’s father, which brings us to the next resource to utilize – other people. Take advantage of living memory and ask your older relatives what they remember. Message your cousin group chat. And don’t be afraid to contact local genealogy pros at the cultural institutions in your area.

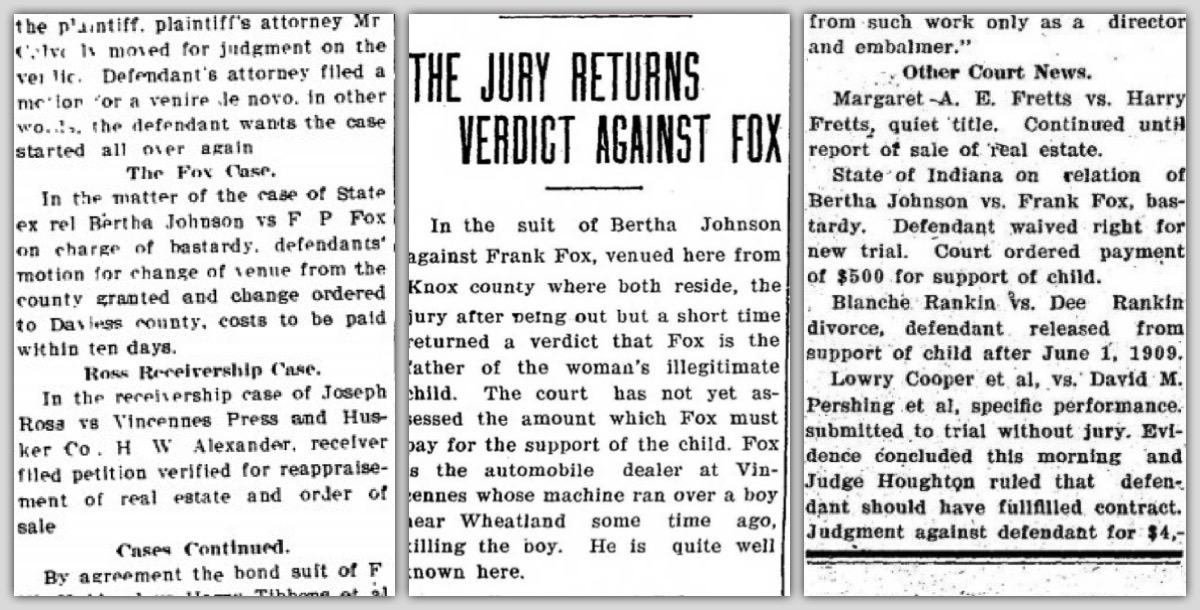

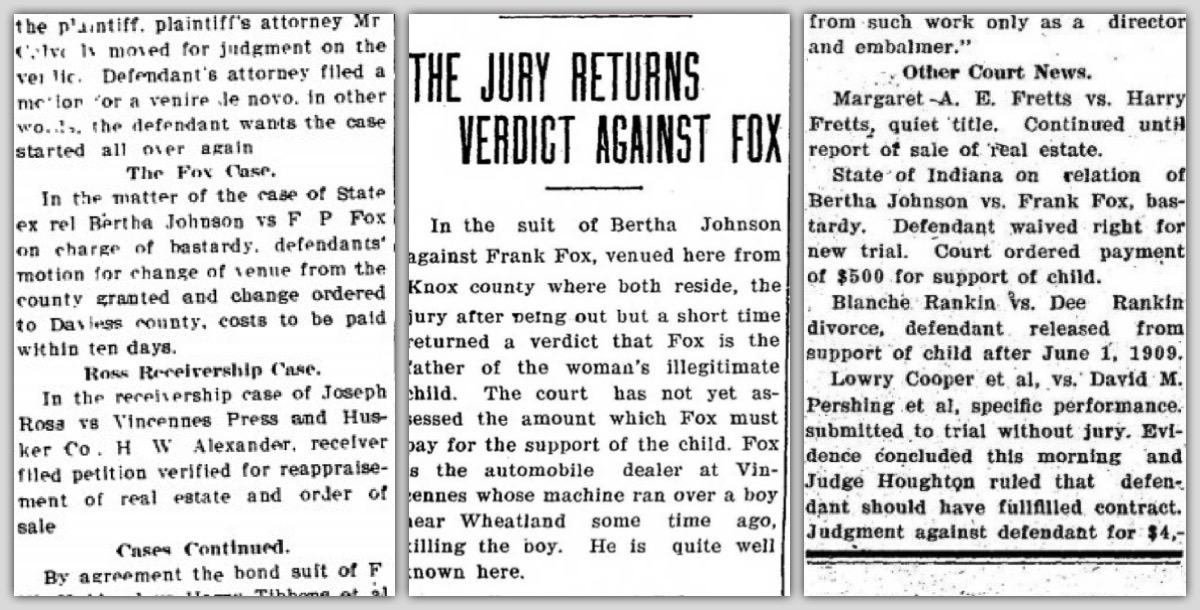

Check local newspapers

Newspapers contain much more than news articles. They also publish birth and marriage announcements, obituaries and legal proceedings. In my case, small town newspapers proved they are, in fact, excellent sources for tidbits about local families. Jamie discovered several notices in the Vincennes Commercial and other papers, which tell us that Bertha Johnson was in fact not pleased with the behavior of her baby’s father and sued him for bastardy in Knox County the same year Lucile was born. He was, it turns out, named Fox — Frank P. Fox, to be precise.

The case was moved to Daviess County at Fox’s request, possibly hoping for a more impartial jury since he and Bertha were both from Vincennes. If that was his intent, it backfired. The jury ruled in Bertha’s favor and awarded her $500 in child support. The Daviess County Weekly Democrat, reporting on the story, also noted that Fox was the same man who hit a child with his car near Wheatland, Indiana, killing him. The newspaper ended by saying, “He is quite well known here.” Absolutely savage.

Left: Vincennes Commercial, Nov. 25, 1908, p. 3; Center and right: Washington Weekly Democrat, May 22, 1909, p. 4; June 5, 1909, p. 3.

If you’re researching someone from Indiana, Hoosier State Chronicles allows anyone to search dozens of Indiana newspapers at no charge. To use subscription databases like Newspapers.com and Ancestry, avoid paying for individual memberships and contact your public library or historical society. They often maintain database subscriptions you can use in-house or from a state IP address for free, as well as collections of newspapers in print or on microfilm, in addition to other resources.

Don’t trust everything you read online

Treat everything you read on the internet with at least as much suspicion as the expired yogurt in your fridge. No database is perfect or will have every record. The records they do have are often rife with errors, which is often why you’ll see so many different spellings for the same person’s name. Database volunteers are human. Census takers are human. So are journalists and coroners and amateur genealogists. And as we all know, humans aren’t perfect.

Don’t just assume that the Bertha Johnson you found listed in a marriage record is your Bertha Johnson. Johnson is almost as common a surname as Smith and Bertha was a very popular first name among the Gilded Age set. Like a bank verifying your identity, recognize key distinguishing information for your person like birth date, mother’s name and birthplace and check them against the sources you find as much is possible. And if you can’t confirm something, even when you’re 99% certain about it, allow for uncertainty. ::hops off soapbox::

5. Get organized

When you’ve reached a stopping point in your research, don’t quit there. Organizing and taking care of your old photographs means that they’ll still be there for your son or granddaughter.

When you’ve reached a stopping point in your research, don’t quit there. Organizing and taking care of your old photographs means that they’ll still be there for your son or granddaughter.

If you’re not maintaining the original order, try grouping them in a logical way. I often organized photo collections by subjects arranged from specific to general, then chronologically within each subject, as I did with Lucile’s collection. Subjects included Lucile’s childhood photographs, portraits of her and her mother, Johnson extended family photos, vacation snapshots, pictures of pets and miscellaneous photographs as a catch-all for the random or unidentifiable images. At other times, I might organize by format or date, separating the more fragile tintypes, ambrotypes and daguerreotypes from paper photographs.

A few housekeeping notes

- Photographs are light sensitive and will fade if left out so they should be stored flat or upright to prevent bending in opaque, acid-free enclosures, envelopes and sleeves.

- Always handle photographs by their backs or edges as the oils on our skin can damage the image.

- Don’t store photographs in musty basements or hot attics. Keep them in spaces with mid-level humidity, 15% at the lowest and 65% at the highest, and below 75 degrees Fahrenheit.

- If you can, avoid doing anything permanent to the photos like writing in pen or using adhesives to stick it in a scrapbook. For more information, check out this blog post from the National Archives on the care and storage of photographs.

- And lastly, consider donating your photo collection to an archive. If you’re downsizing, lack storage space or don’t have anyone to leave your collection to, an archive could be a viable option depending on the content. Archives keep the materials safe, ensuring their survival for future generations, while allowing the public, including your family and researchers, to access them as needed.

This blog post was written by Rare Books and Manuscripts librarian Brittany Kropf. For more information, contact the Rare Books and Manuscripts Division at 317-232-3671 or by using “Ask-A-Librarian.”

This blog post was written by Rare Books and Manuscripts librarian Brittany Kropf. For more information, contact the Rare Books and Manuscripts Division at 317-232-3671 or by using “Ask-A-Librarian.”