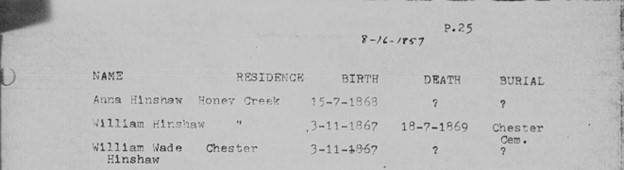

If you run with the genealogy crowd, you may be familiar with name William Wade Hinshaw as the author of the Encyclopedia of American Quaker Genealogy. What you might not know is that during his lifetime, he was known as an opera singer.

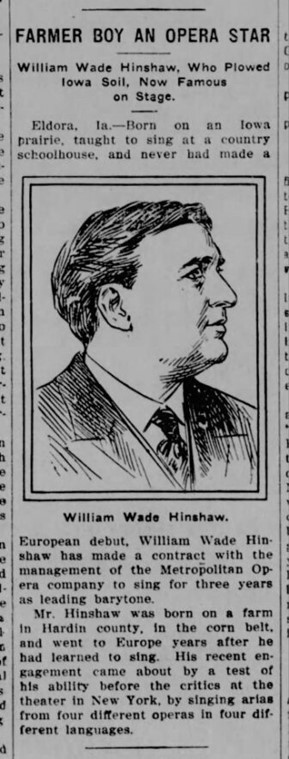

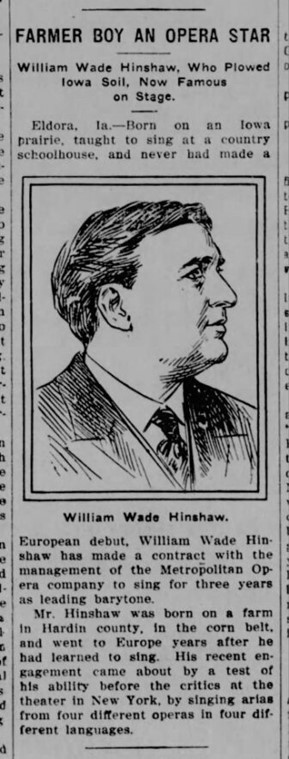

William Wade Hinshaw was born in Providence Township, Hardin County, Iowa on Nov. 3, 1867 to birthright members of the Religious Society of Friends (Quaker), Thomas Doane Hinshaw and Anna Harriet Lundy. The Hinshaws were members of the Honey Creek Monthly Meeting in Hardin County, Iowa.

The birthright membership of William Wade Hinshaw’s parents gave them automatic membership in the Religious Society of Friends, due to being born of Quaker parents. The Hinshaw family had been Quakers since the early 1700s in Ireland, coming to the American colonies in the mid-1700s and settling in North Carolina. The Lundy family had been Quakers since the late 1600s, with the arrival of Richard Lundy in Pennsylvania.

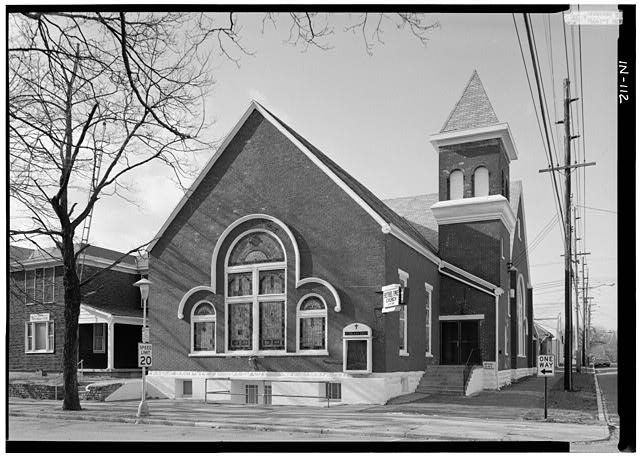

Honey Creek Meeting House.

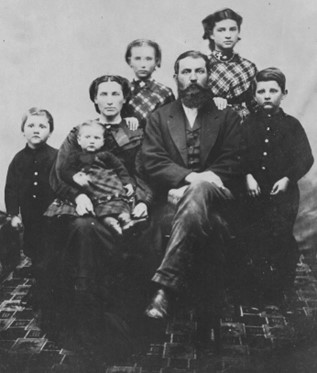

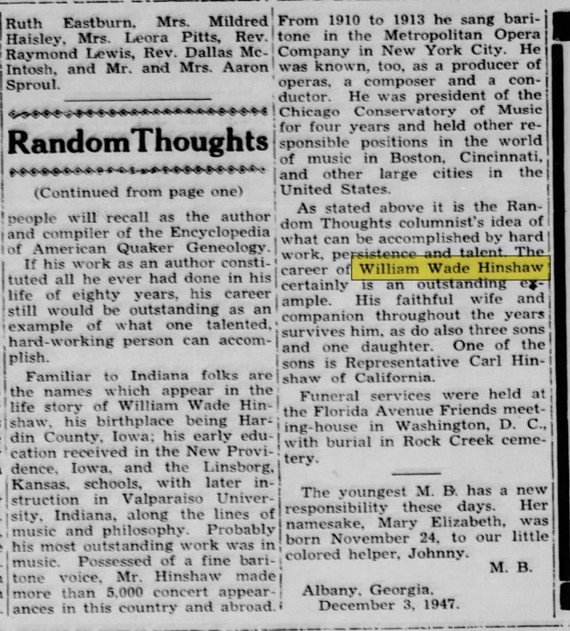

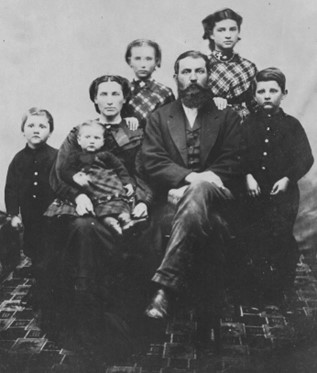

Thomas Doane Hinshaw family. William Wade Hinshaw on the left.

Playing the cornet at 9 years of age and then leading a brass band at 13, Hinshaw was educated at the Chester Meeting School and later attended the New Providence Friends Academy in Hardin County, Iowa.

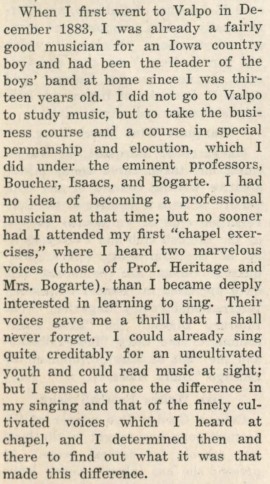

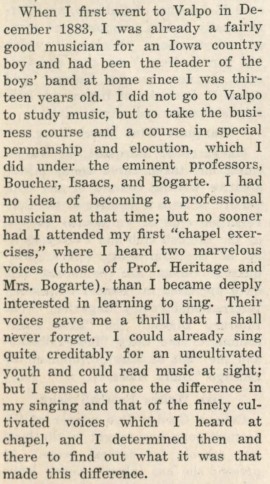

In 1893, he attended Valparaiso University in Indiana, graduating in 1890. While attending Valparaiso University, his love of music deepened. In his own words:

Valparaiso University Alumni Bulletin, June 20, 1930.

While attending the university, he also managed to direct a Methodist Episcopal choir. This is where he met Anna T. Williams, a member of the choir.

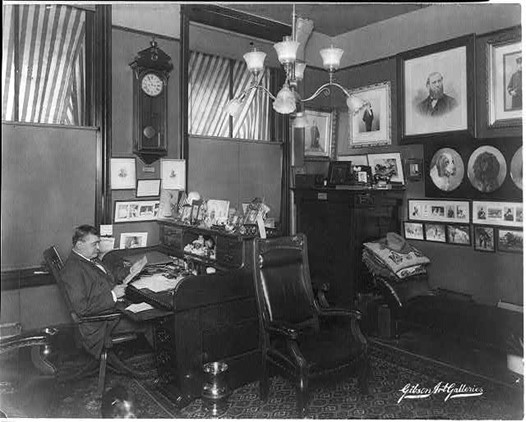

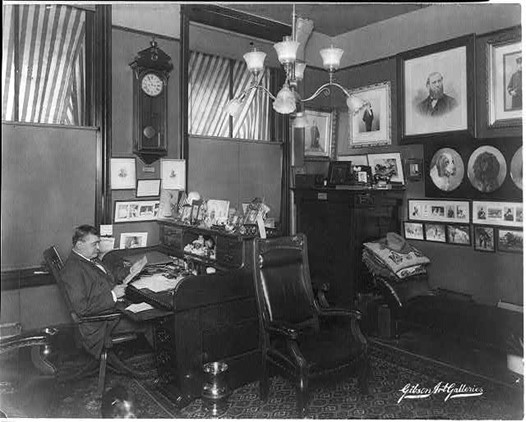

William A. Pinkerton at his desk.

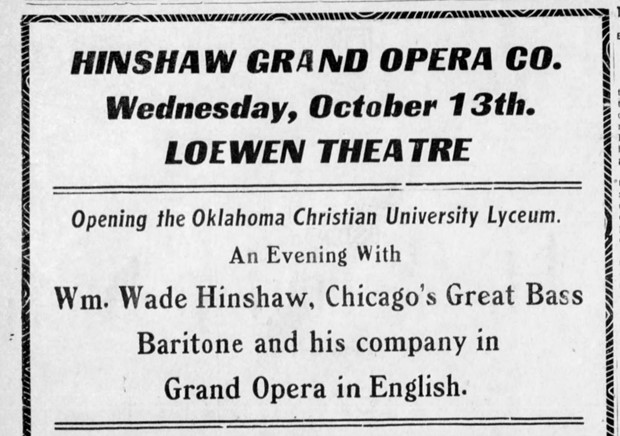

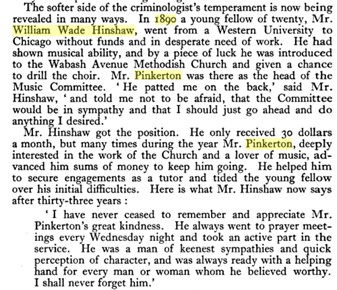

In 1890, the newborn graduate made his way to Chicago, meeting with William A. Pinkerton – son of Allen Pinkerton and successor to the Pinkerton Detective Agency – to secure a job directing a church choir. The Landmark magazine details that meeting.

Page 96 from The Landmark, the monthly magazine of the English-Speaking Union, Volume VI, 1924.

1893 was an eventful year for Hinshaw. In the summer of that year, he performed for the first time on a public stage at the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893. He probably sang as part of the Apollo Musical Club – of which he was a member.

Then, in September of 1893, he married Anna T. Williams, the woman he met while directing a church choir in her hometown of Centerville, Iowa.

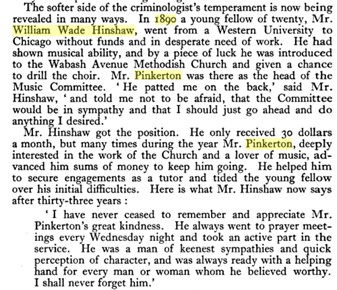

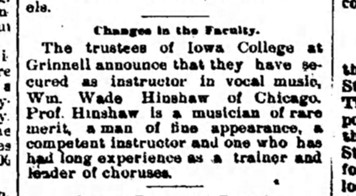

1894 was the year of the birth of his first child, Carl W. Hinshaw, and the year that he landed a new job as a music instructor at Iowa College, Grinnell.

Estherville Daily News, Aug. 9, 1894.

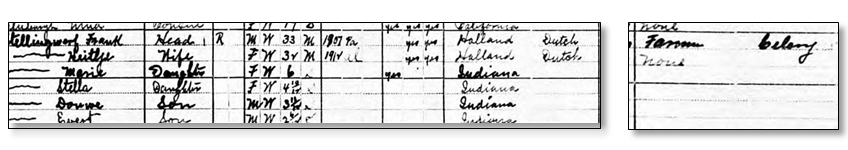

While Hinshaw was the head of the Music Conservatory at Valparaiso University from 1895-1899, his wife Anna attended the university and became a mother to William Wade Jr. in 1899.

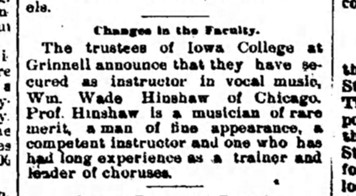

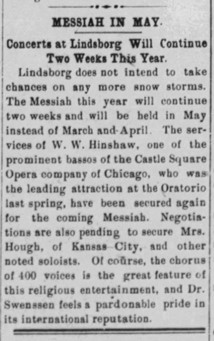

In 1900, the Hinshaw family was living in Chicago and William had listed his occupation as opera singer, as by then he was singing with the Castle Square Opera Company.

Abilene Weekly Reflector, Feb. 27, 1902.

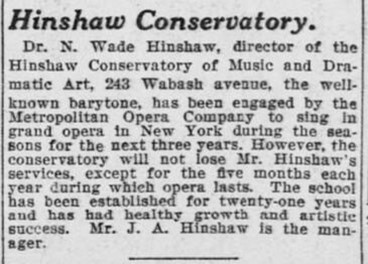

Throughout the 1900s, he directed and taught at the Hinshaw School of Music, part of the Chicago Conservatory of Music.

Auditorium Building, Chicago, Illinois.

According to the 1905 Chicago City Directory, Hinshaw the music instructor was living on the ninth floor of the Auditorium Building. Hinshaw must have found this location of residence convenient as he also performed in the building’s theater as part of the Apollo Musical Club.

On Nov. 30, 1905, Anna died of pneumonia, leaving the care of their four children – three boys and a girl – to William. The Hinshaw family made their home in Valparaiso, Indiana after her death.

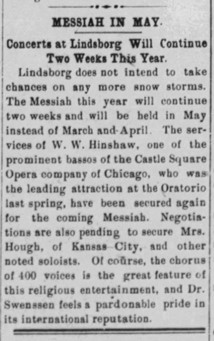

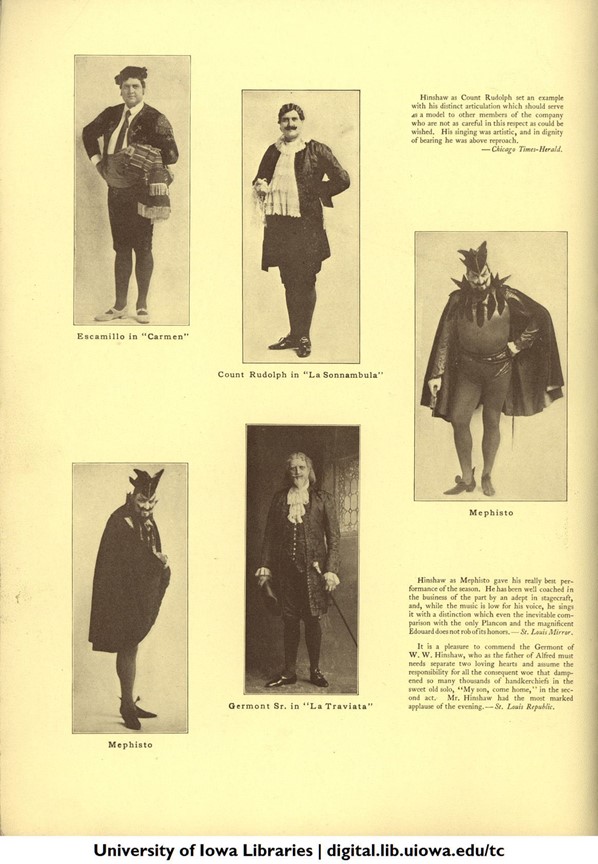

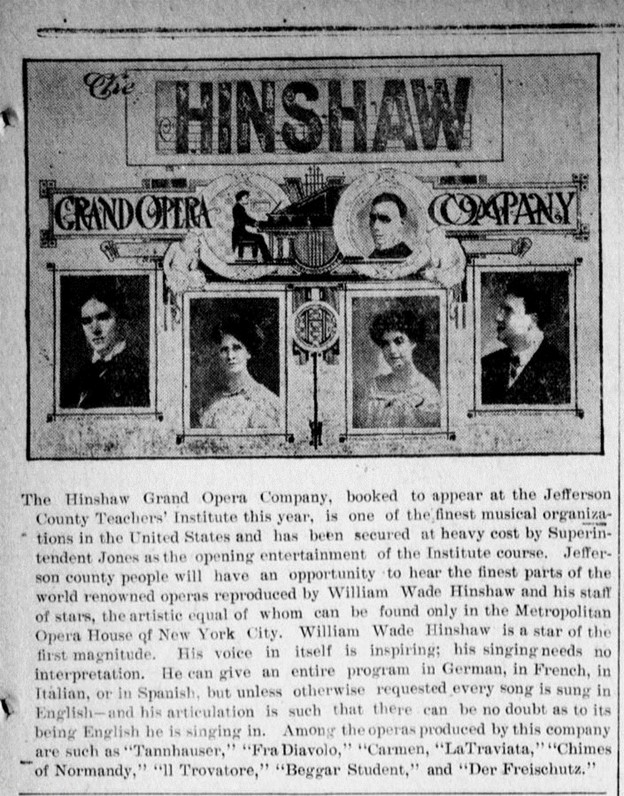

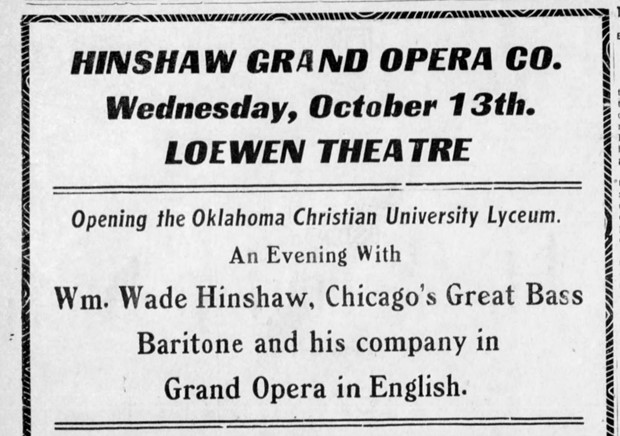

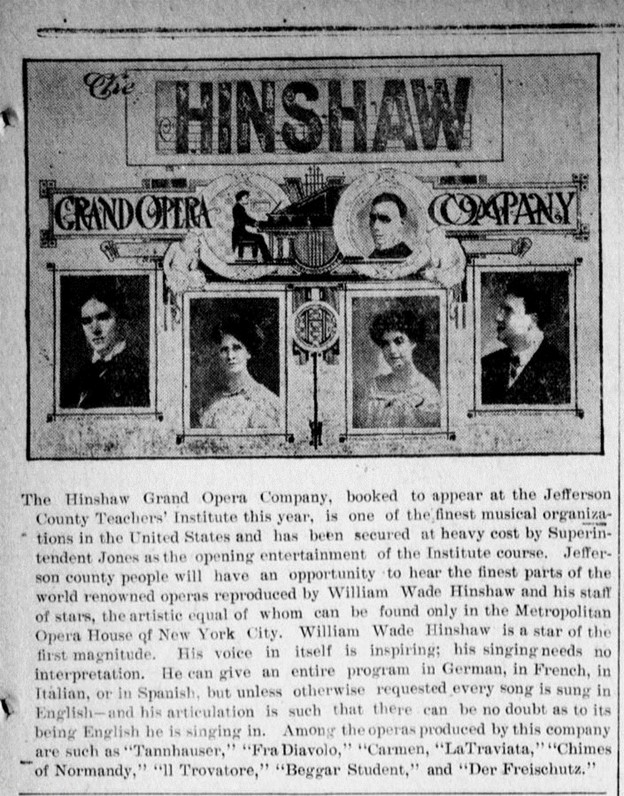

However, by 1909 things were looking sunnier, as Hinshaw was the owner of his own opera company.

The Enid Daily Eagle, Oct. 3, 1909.

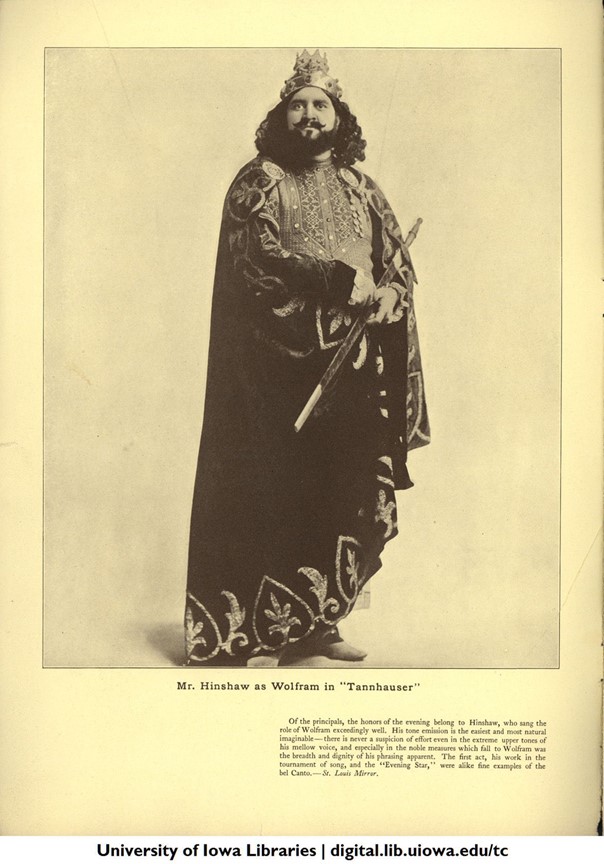

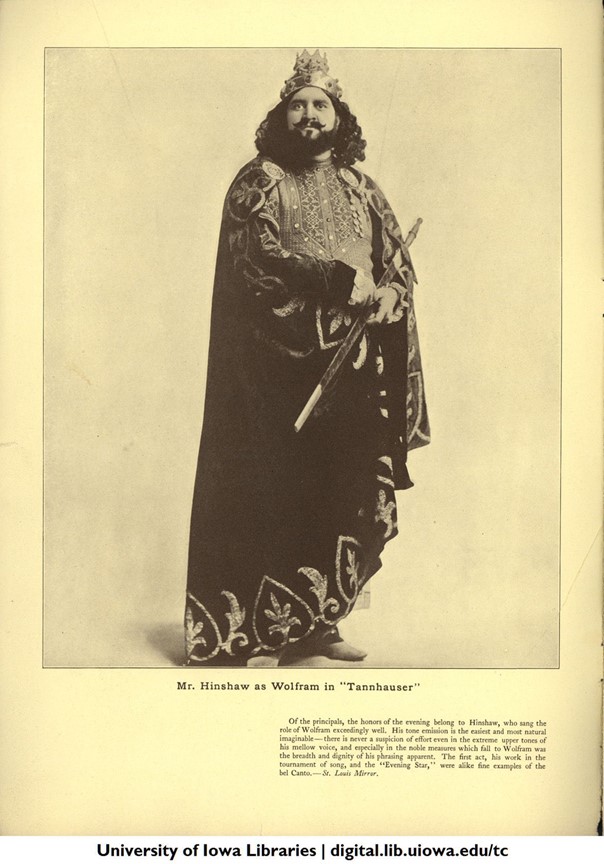

By 1910, life was even better when Hinshaw debuted at the Metropolitan Opera House on Nov. 16, 1910 in a production of Tannhauser.

Chicago Examiner, Aug. 14, 1910.

For all of 1910, William Wade Hinshaw is the talk of the town.

Advertisement from The Morning Chronicle, June 10, 1910.

The Silver Messenger, Oct. 4, 1910.

The Star, Nov. 16, 1910, page 3.

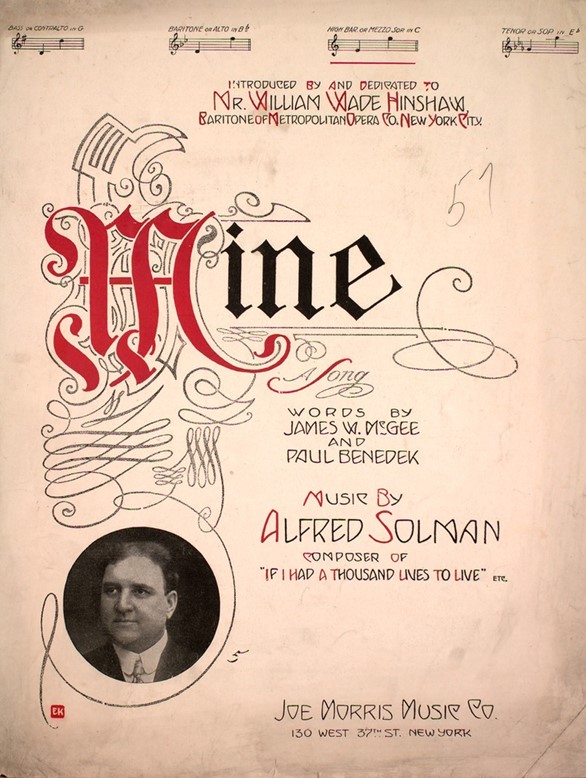

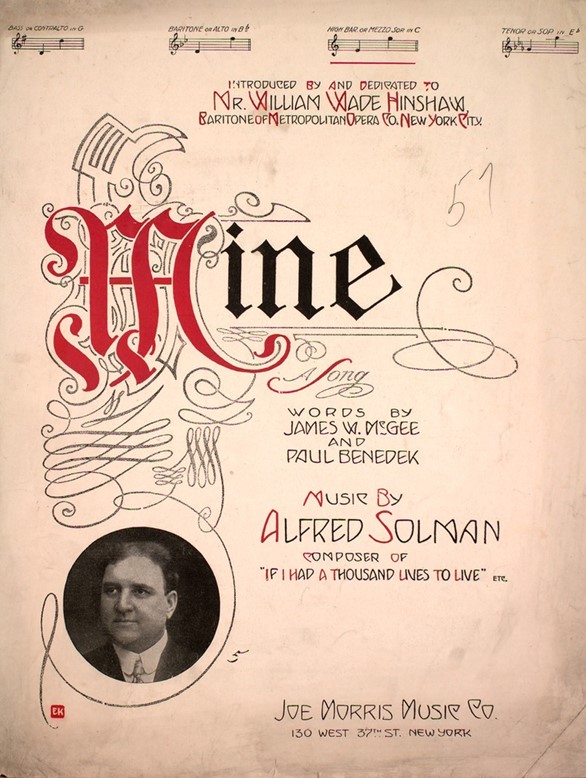

Sheet music, 1911.

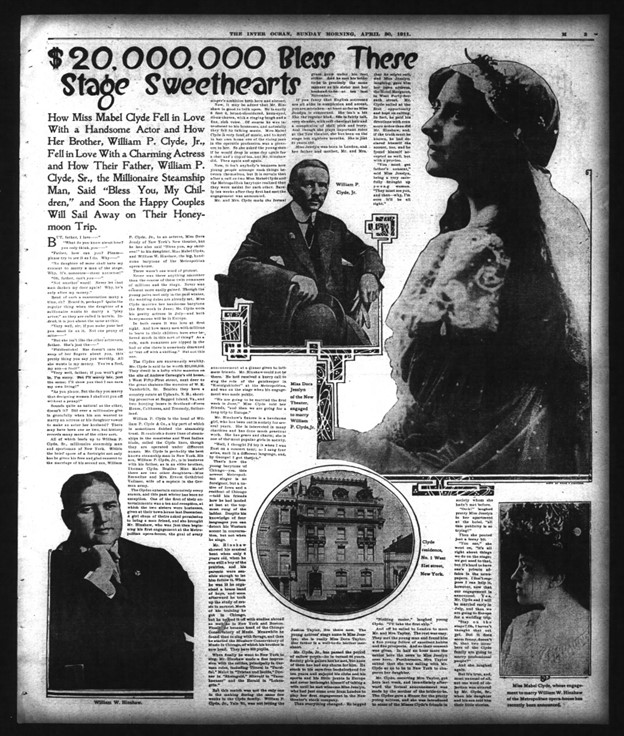

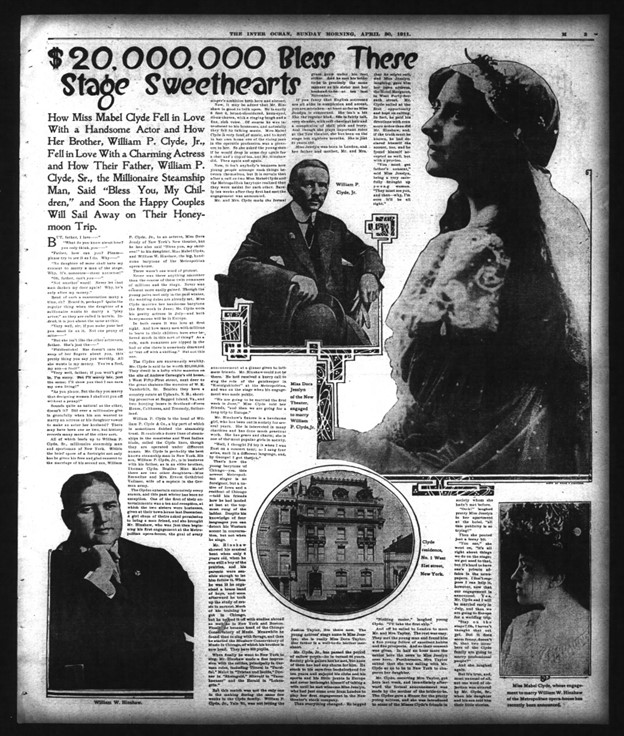

In December of 1910, he met Mable Clyde at tea held at her parents’ home in New York. By March of 1911, the couple were engaged to be married. The marriage made the society page.

The Inter Ocean, April 30, 1911, page 29

Hinshaw was singing at the Austrian Das Rheingold Festival in the summer of 1912. He would return to New York in October to perform again with the Metropolitan Opera.

The steamship George Washington, baritones Antonio Scotti, Pasquale Amato and William Hinshaw, Oct. 29, 1912.

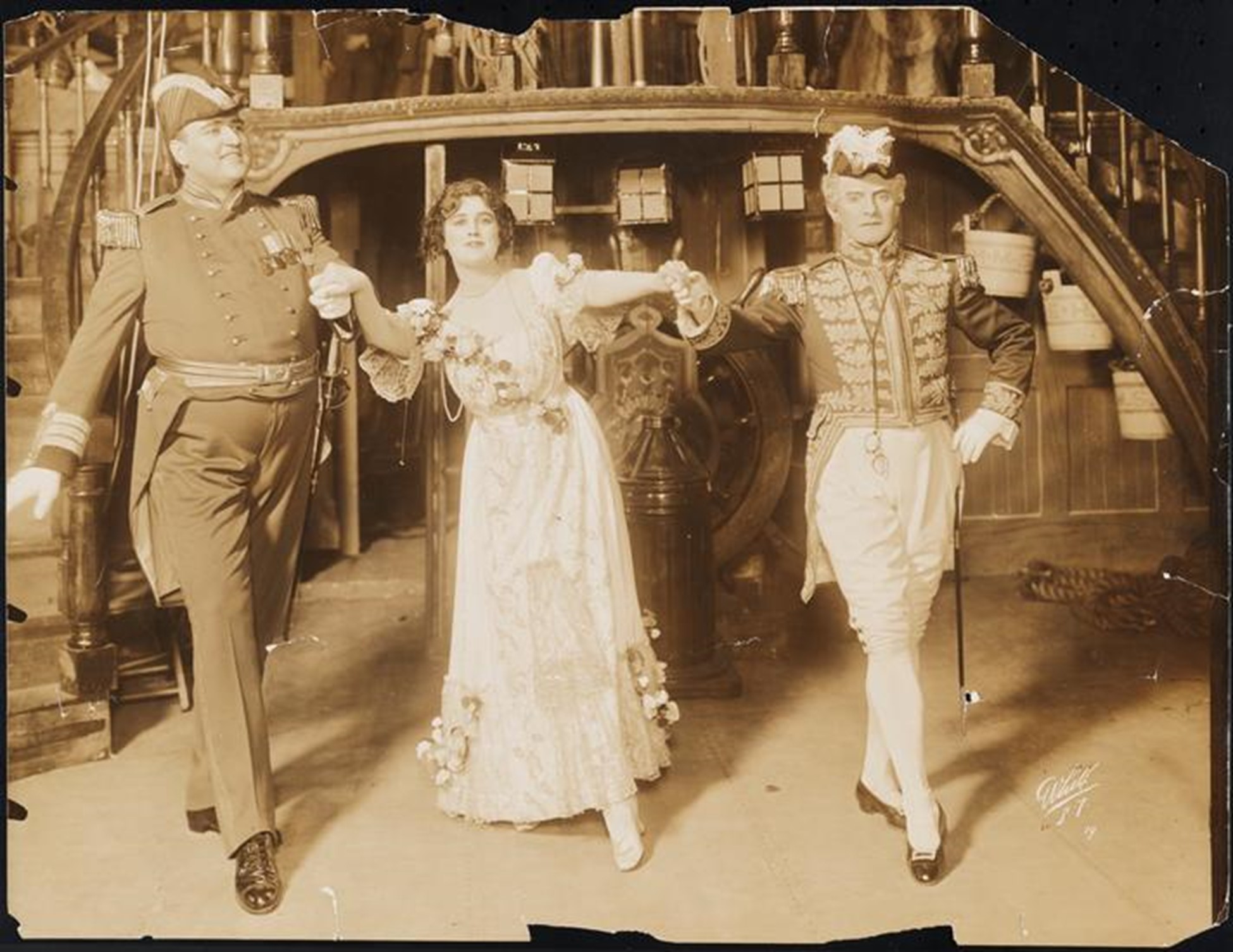

On March 16, 1913, he played Carnegie Hall. He followed that performance the next year in April and May when he appeared on Broadway in a production of the “H.M.S. Pinafore.”

Music News, Volume 5, Issue 1, 1913.

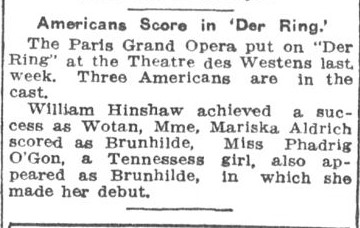

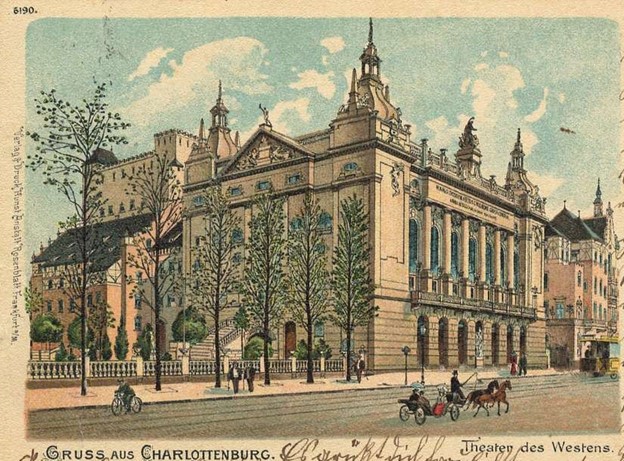

In July of 1914, Mr. and Mrs. Hinshaw were in Berlin, Germany. Mr. Hinshaw was singing with the Paris Opera at the Theatre des Westens.

The Fargo Forum and Daily Republican, July 4, 1914.

Theatre des Westens, Berlin Germany, German postcard.

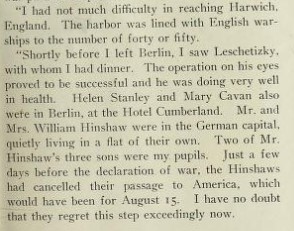

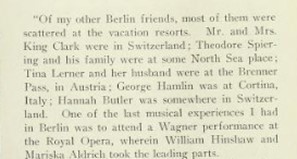

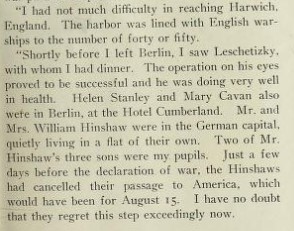

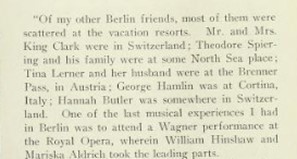

However, if you know your history, you may already suspect what event is coming up. World War I was declared on July 28, 1914. A fellow American musician returning from Germany, reported to the Musical Courier:

Musical Courier, Aug. 19, 1914 page 23.

Musical Courier, Aug. 19, 1914 page 23.

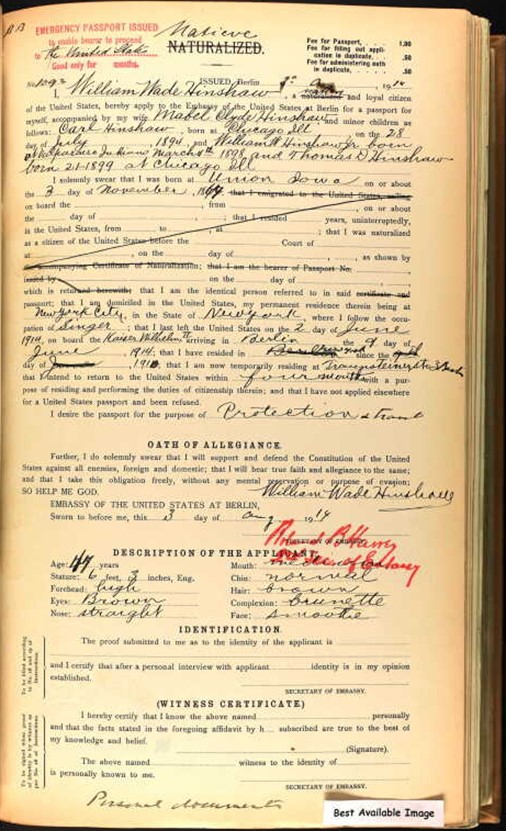

In August of 1914, U.S. Consular Officers in Europe were authorized and advised to issue emergency passports to those U.S. citizens stranded in Europe after the declaration of war. The emergency passports issued to those stranded provided citizenship verification for protection and the paperwork needed to safely seek passage back to the United States.

That August, Hinshaw applied for an emergency passport.

Hinshaw’s emergency passport application, August, 1914.

After first securing passage for the Hinshaw children earlier in September, Mr. and Mrs. Hinshaw left Rotterdam on Sept. 23, 1914 and arrived in New York on Oct. 2, 1914.

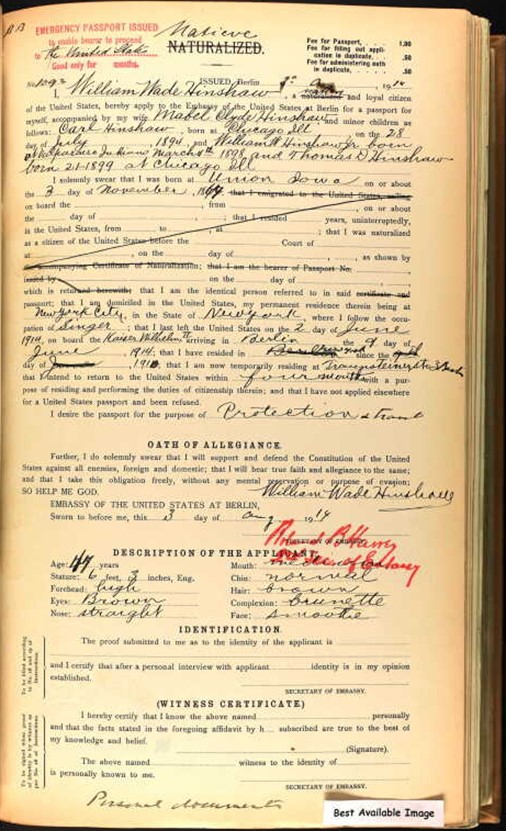

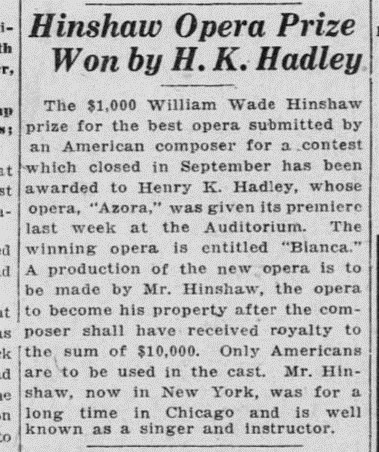

In 1916, he established the Hinshaw Opera Prize of $1,000 for the composer of a new American Grand Opera. If won today, the prize amount would equal $23,000-$24,000.

Chicago Examiner, Dec. 30, 1917.

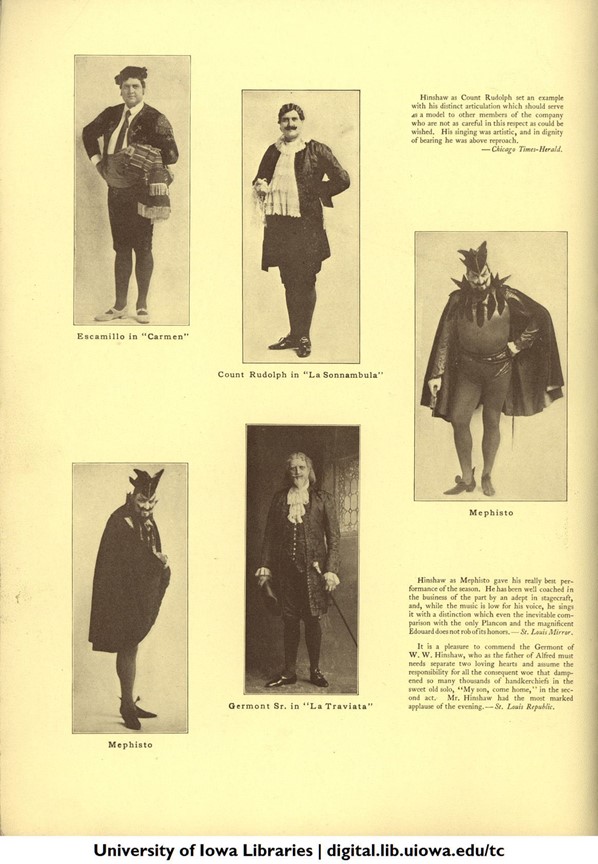

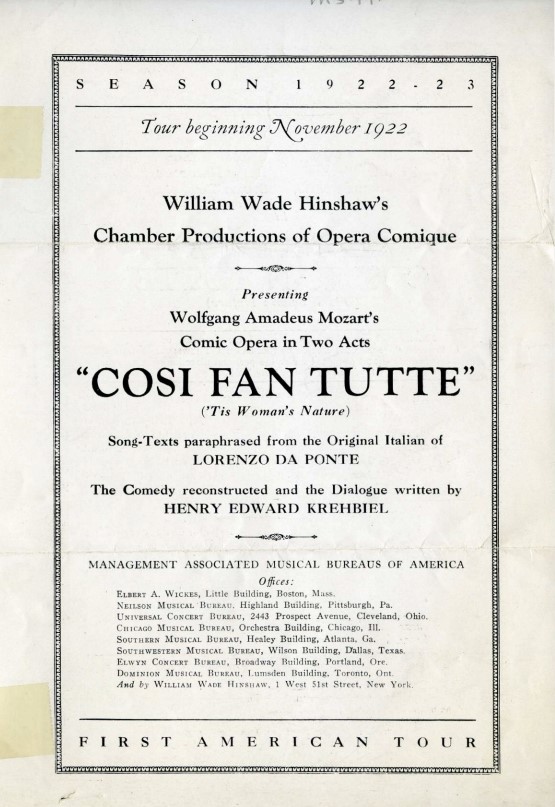

During the 1920s and 1930s, he was the director of his own opera touring company. Throughout his career as an opera singer, he supported and sang English opera, which are operas that have been translated into English from French, Italian or German to make them more accessible to an English-speaking audience.

While Hinshaw’s children found a home base in Ann Arbor, Michigan with their aunt Lydia Fremont Hinshaw Holmes, their father established his home in New York City with his wealthy in-laws.

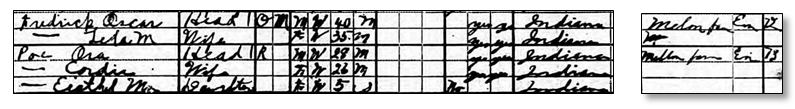

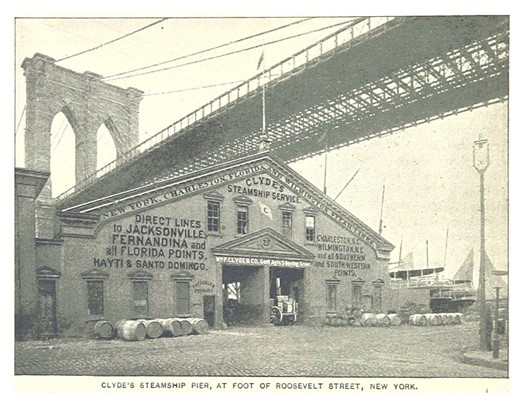

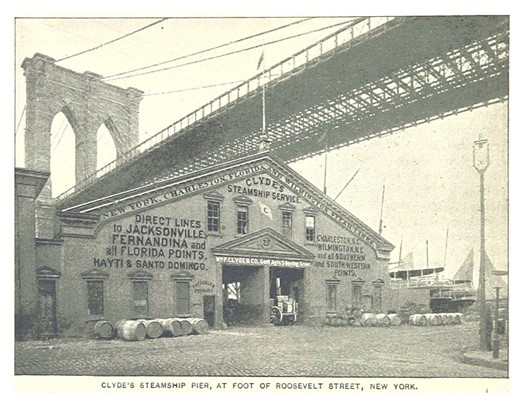

William Wade Hinshaw’s father-in-law was William P. Clyde, owner of the Clyde Steamship Company. The Clyde family lived on 5th Avenue in a house formerly owned by Andrew Carnegie. According to the 1920 census, 26 people were living in the house – 13 of those being servants. Of the remaining 13 persons – besides Hinshaw who listed his occupation as opera manager – their occupations are listed as “none.”

King’s Handbook of New York City, page 100, British Library.

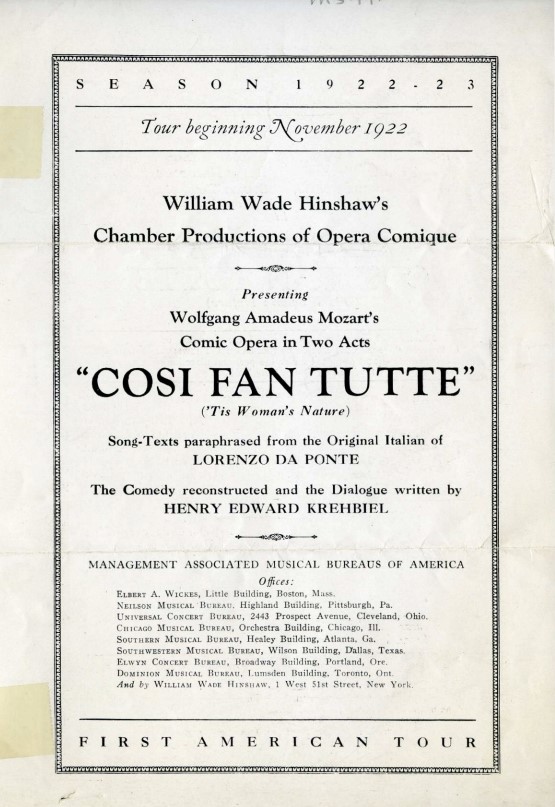

Cover page of the program for Cosi Fan Tutte, 1922, Multnomah County Library, digital gallery.

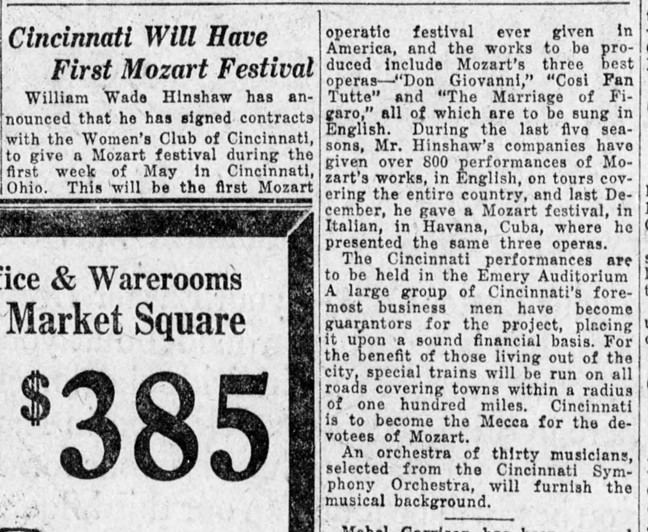

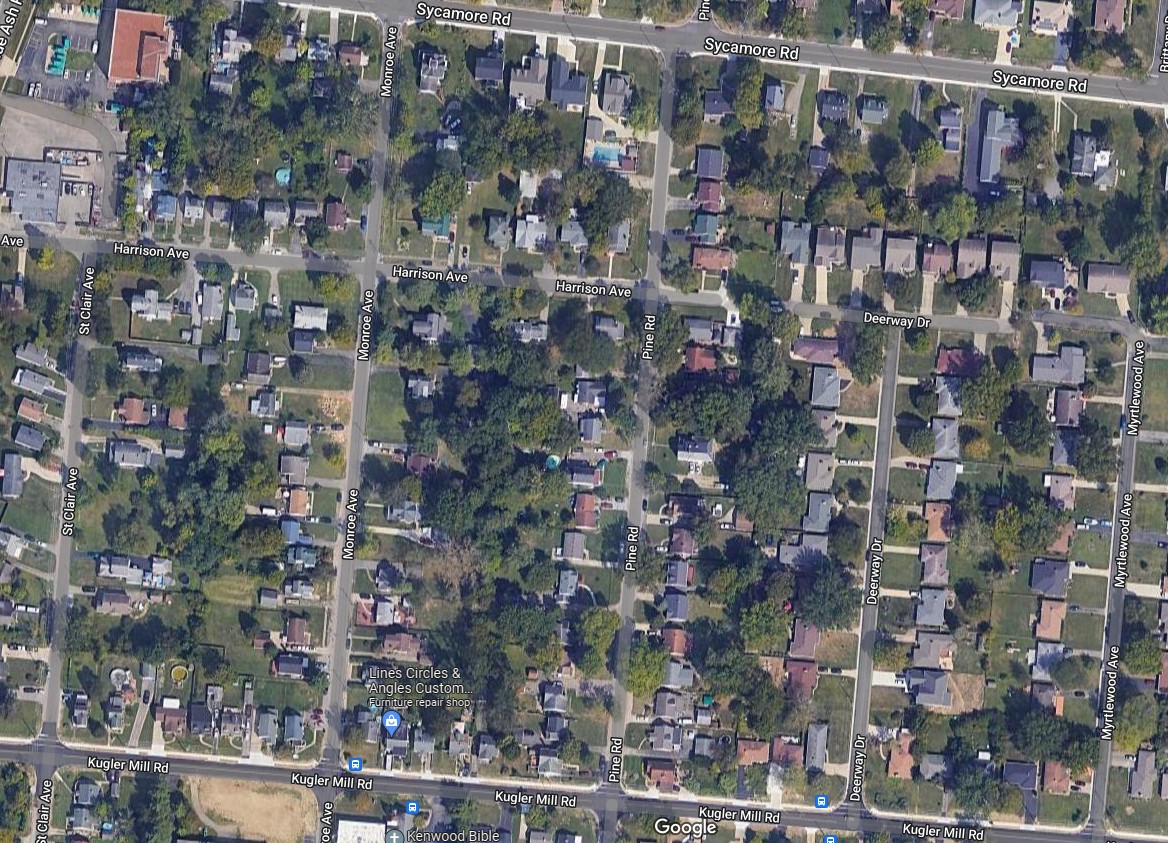

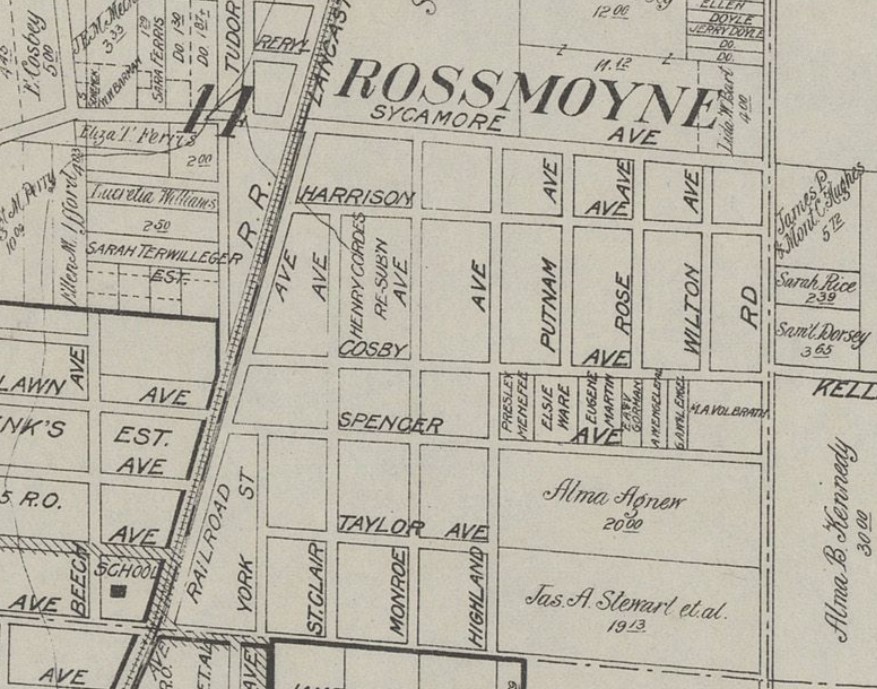

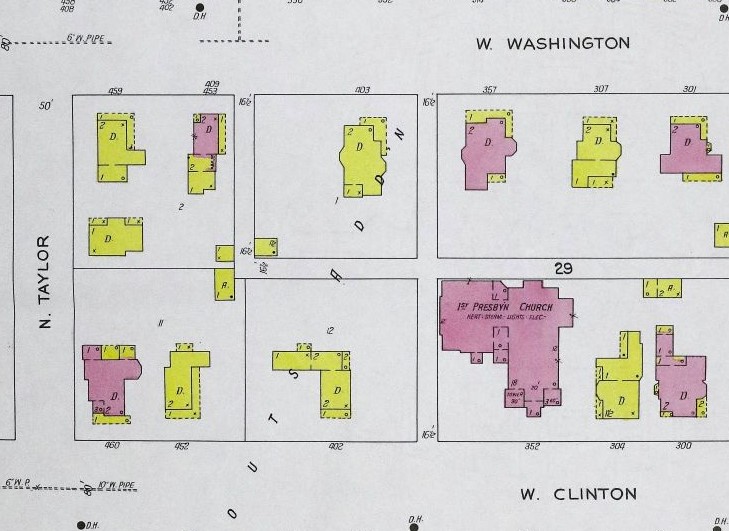

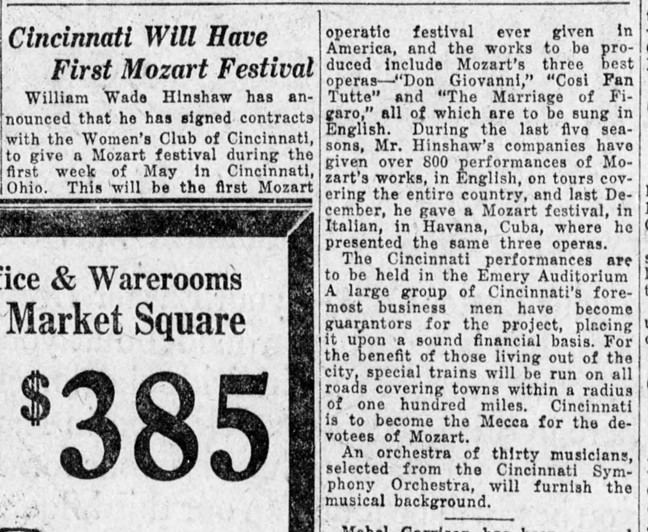

The Evening News, March 23, 1926, page 4. 1926 – First American Mozart Festival in Cincinnati, Ohio.

Michigan Daily, May 10, 1931.

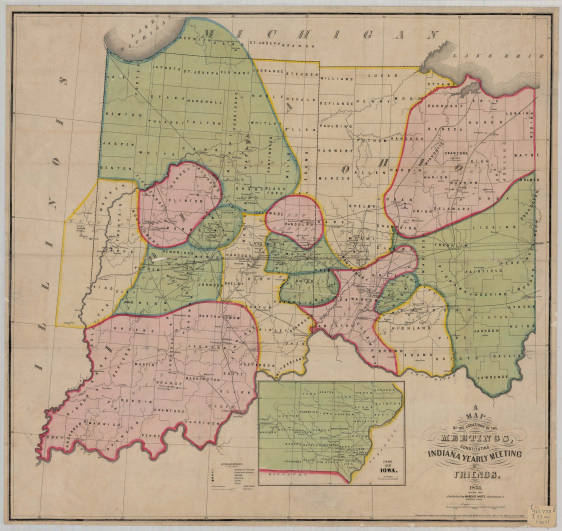

The 1930s found Mr. and Mrs. Hinshaw living in Ann Arbor, Michigan. William owned a music shop, and he spent the last two decades of his life actively researching genealogy. Involved in family research by at least 1923, perhaps, as he stopped traveling for opera performances and settled down, he now had more time for genealogy research. He was assisted by genealogist Edna Harvey Joseph in his research of Quaker monthly meeting records for his family genealogy. She suggested that with all the money and time spent gathering monthly meeting records for his family, that perhaps entire monthly meeting records could be copied – not just those that pertained to his ancestors. This suggestion eventually results in the creation of the Encyclopedia of American Quaker Genealogy.

The research that would result in the encyclopedia was underway by at least 1934, as reported by the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting. The first volume of the encyclopedia was published in 1936 by the Edwards Brothers of Ann Arbor and distributed by the Friends Books and Supply House of Richmond, Indiana.

Advertisement for the Friends Book and Supply House from the Richmond Palladium, April 28, 1921.

Having started so late in life on his genealogical endeavor, at his death in 1947, most of Hinshaw’s obituaries across the nation are headlined by the fact that he was the father of California Congressional Representative Carl Hinshaw. Secondary to his time as an opera singer – if genealogy is mentioned at all – Hinshaw is called an amateur genealogist.

However, at least one obituary highlighted his contributions to the world of genealogy research:

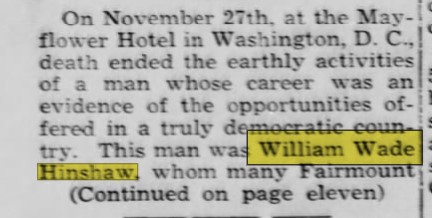

The Fairmount News, Dec. 11, 1947.

The Fairmount News, Dec. 11, 1947.

The Fairmount News, Dec. 11, 1947.

William Wade Hinshaw’s life presents this lesson for established genealogists and anyone temped to pursue family history: However many passions you have in life, there is always time for genealogy.

This blog post is by Angi Porter, Genealogy Division librarian.

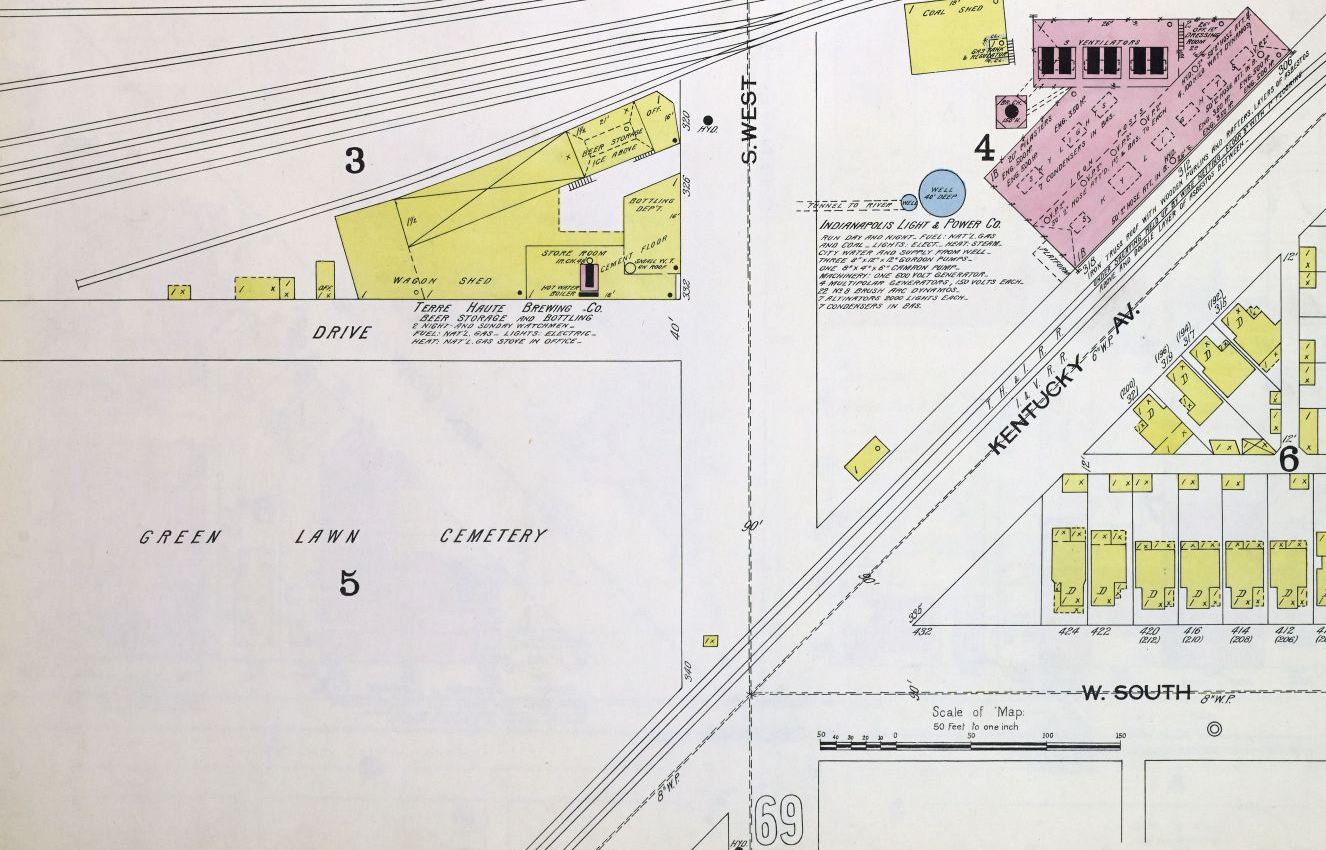

Resources in the Indiana State Library Collection

Encyclopedia of American Quaker Genealogy; call number: ISLG 929.102 F911h, Volumes 1-6

Genealogy Manuscript: Edna Harvey Joseph collection 1851-1969; call number: Mss G ISLG G.053

Ancestral Lineage of William Wade Hinshaw; call number: Pam. ISLG 929.2 H UNCAT. NO. 1

Online resources

Encyclopedia of American Quaker Genealogy, Volumes 1-3

“The Lundy Family and Their Descendants of Whatsoever Surname : with a biographical sketch of Benjamin Lundy”