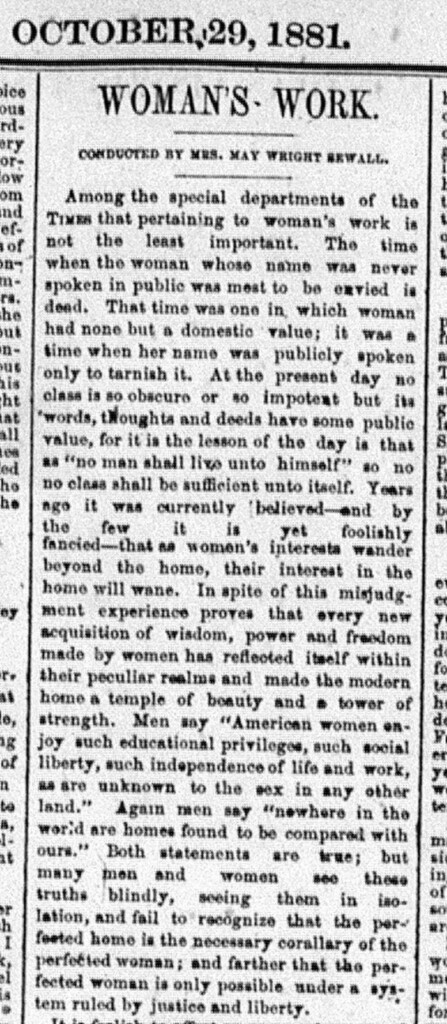

Indiana engendered more than one leader of the U.S. women’s suffrage movement. The most recognized of these Hoosier suffragists today are probably May Wright Sewall and Ida Husted Harper. Marie Stuart Edwards of Peru, Ind. was among the next generation of activists to take up the cause.

Marie Stuart Edward, circa 1910s. (SP021)

In many ways, Edwards was typical of women’s suffragists from Indiana. Born on Sept. 11, 1880, she was one of two children in an upper middle-class family from Lafayette, Ind. Edwards received a first-class education, having graduated from Smith College in 1901 and had a supportive husband, Richard E. Edwards (1880-1969), who she married in 1904.

Over six feet in height with brown hair and eyes, Edwards was described as “a woman of brilliant, buoyant personality” in the Carroll County Citizen-Times. Not one for idle hands, Edwards oversaw designing and decorating for her husband’s business, the Peru Chair Company, while raising her only child, Richard Arthur (1909-1984), and taking an interest in social reform.

Marie Stuart Edward and her son, Richard Arthur, 1912. (SP021)

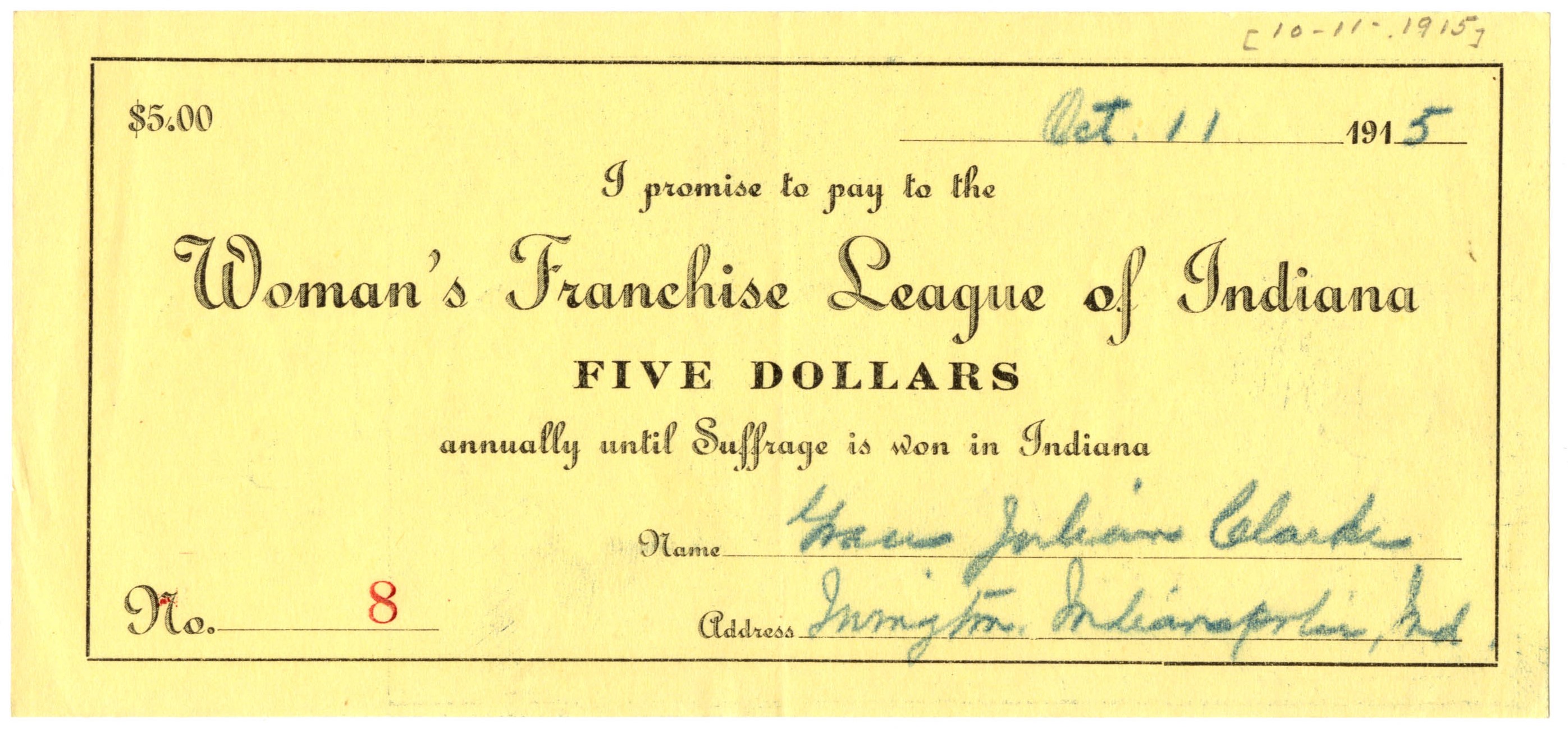

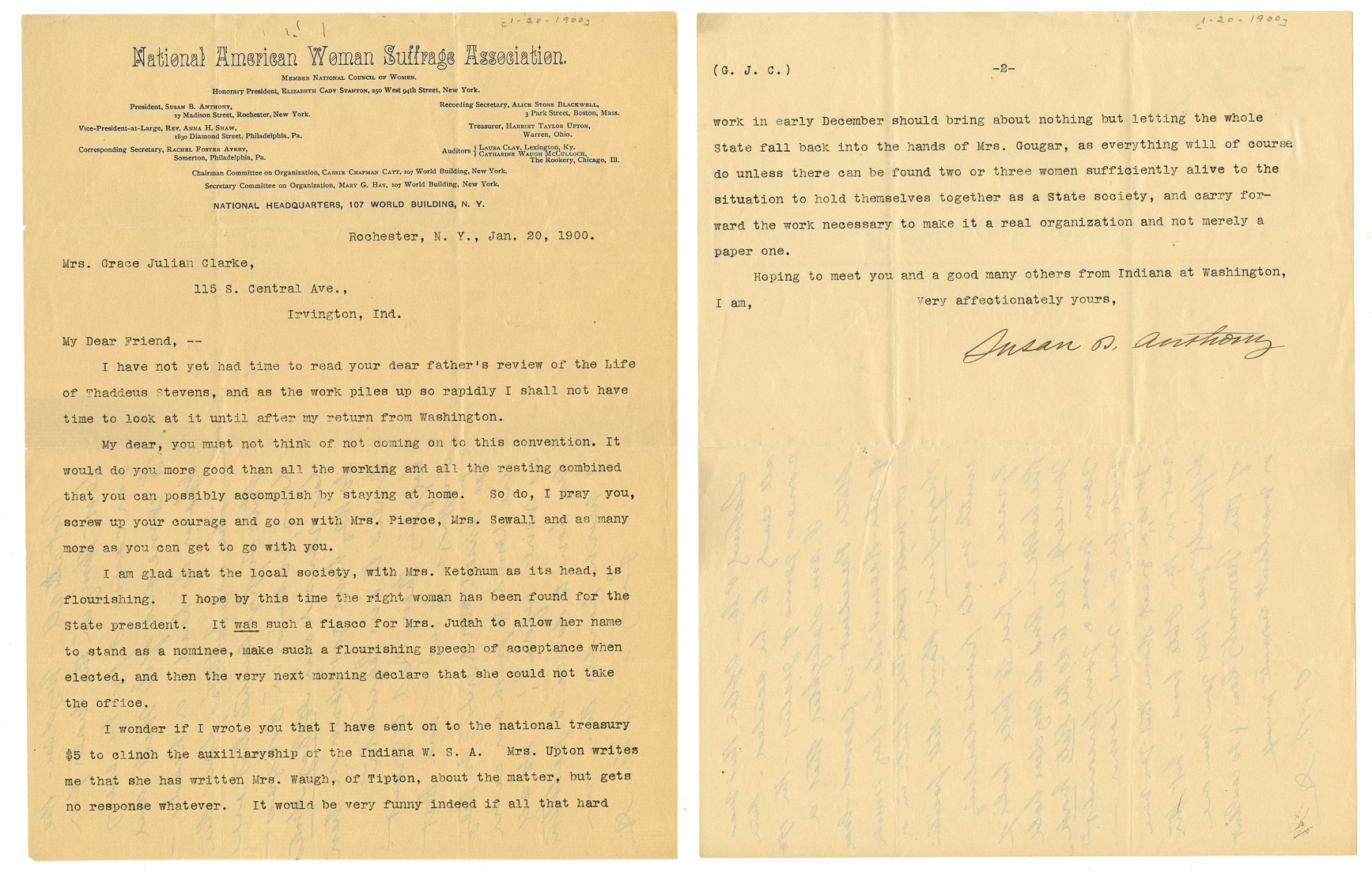

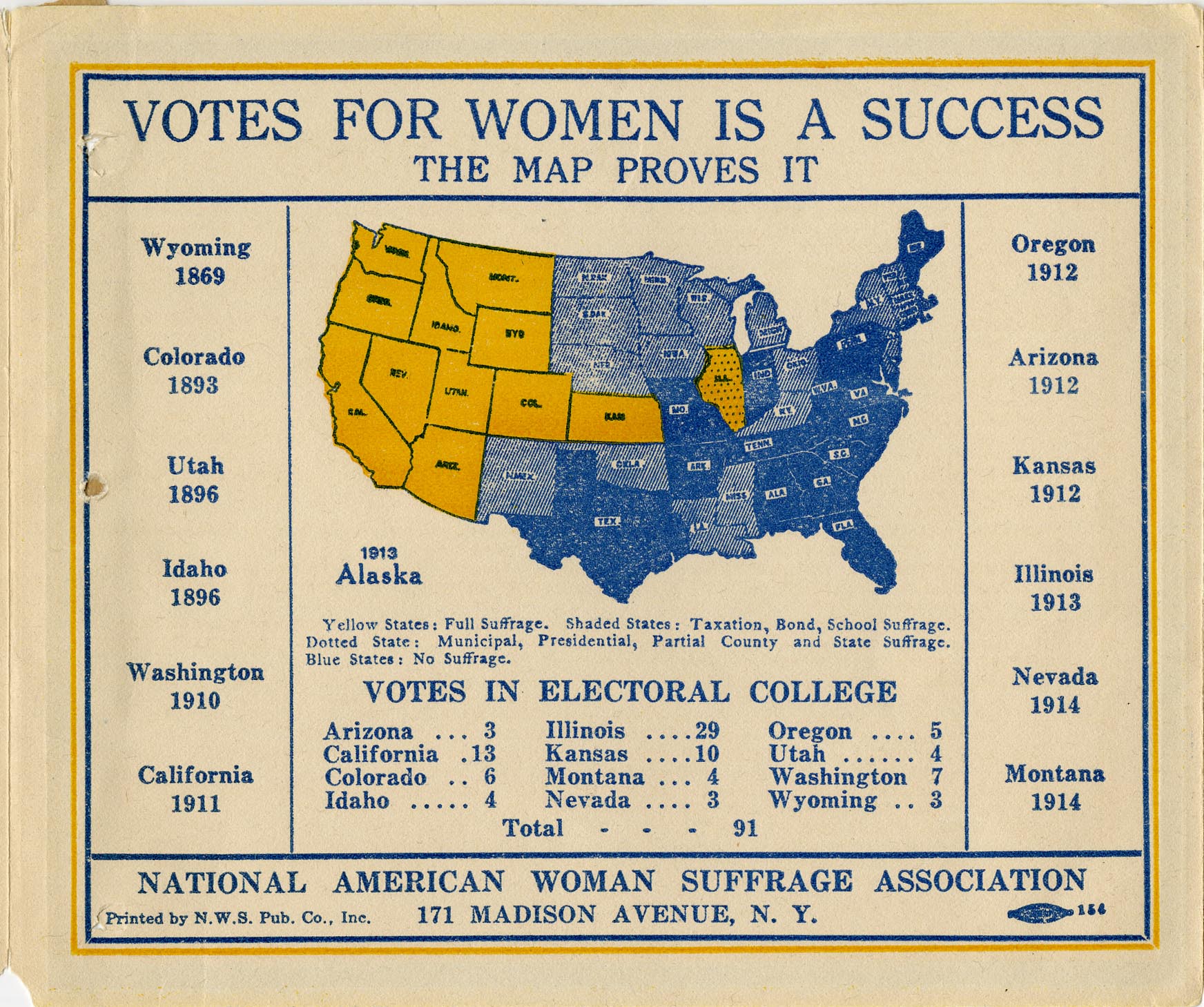

Alongside her contemporaries Grace Julian Clark and Luella McWhirter, Edwards belonged to various women’s clubs and desired the right to vote so she might effect social change. Also, like many Hoosier suffragists, Edwards lent her support to the mainstream suffrage movement, carefully keeping away from the more radical factions, such as Alice Paul’s National Woman’s Party.

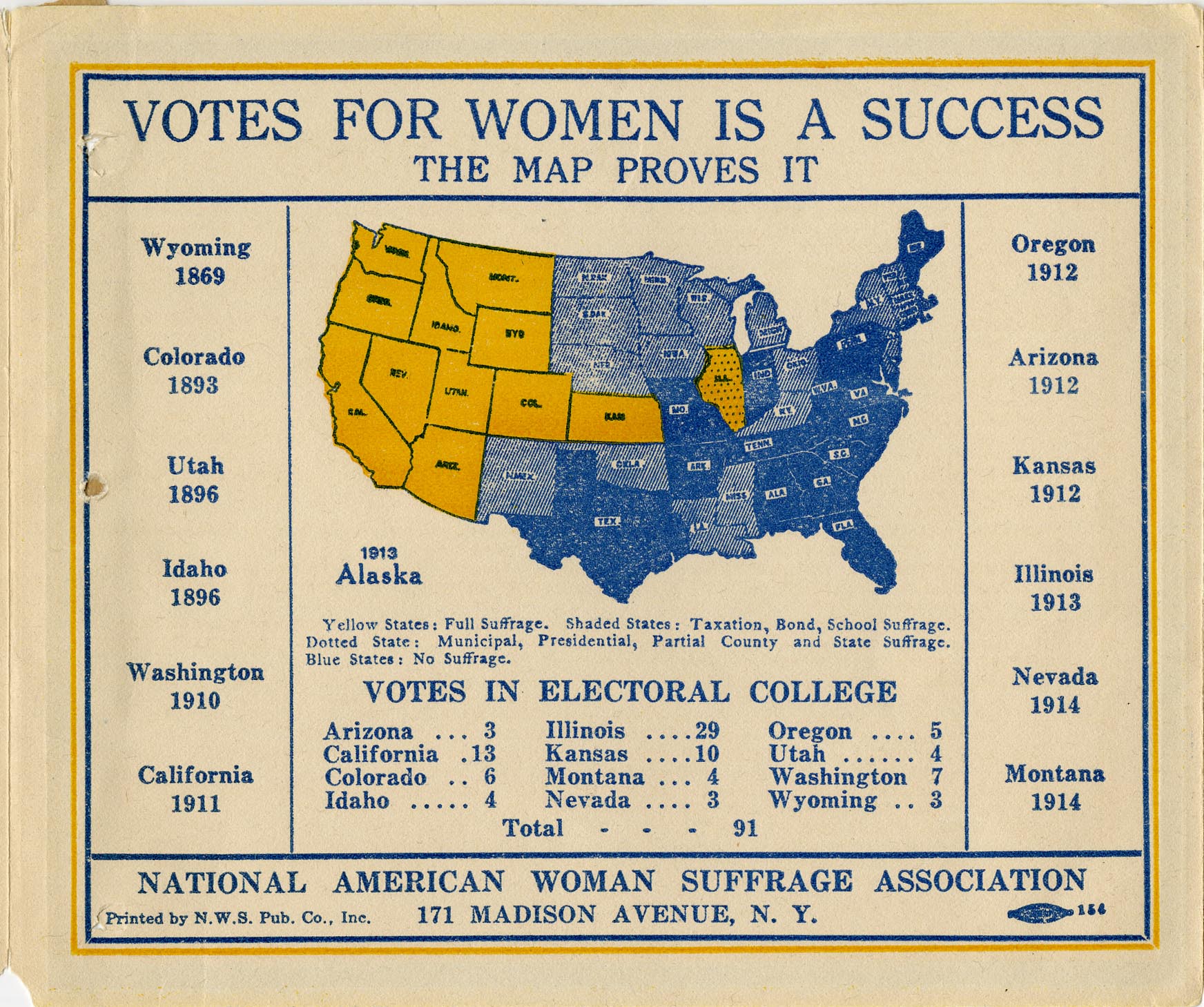

Map of states where women could vote in 1914. From NAWSA pamphlet (S3355).

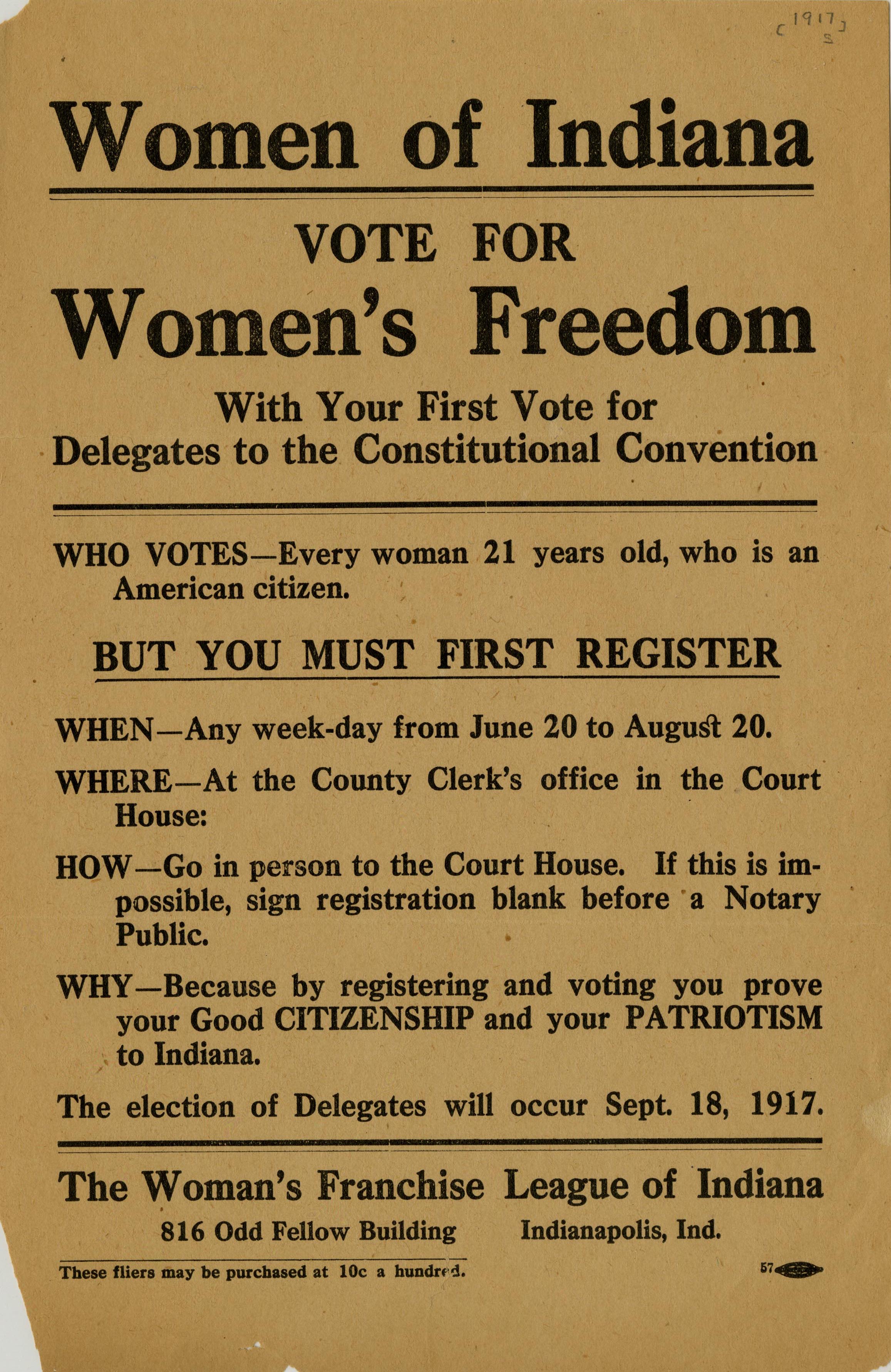

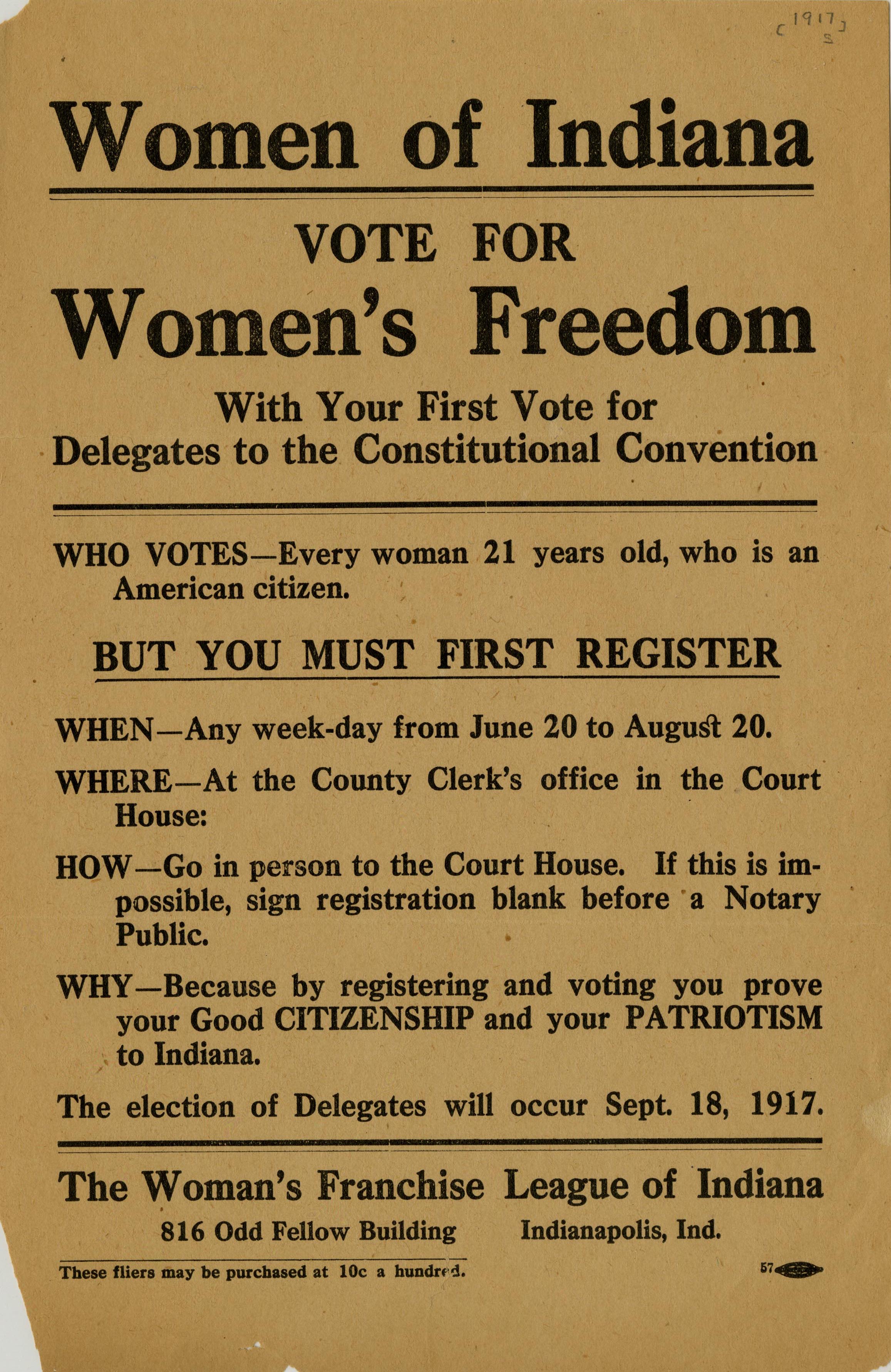

In 1917, Edwards was elected president of the Woman’s Franchise League of Indiana, an organization associated with the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). That same year, the Indiana General Assembly passed the Maston-McKinley Partial Suffrage Act, granting Hoosier women the right to vote in municipal, school and special elections.

Woman’s Franchise League of Indiana leaflet before repeal of partial suffrage law, 1917. (S3355)

Between 30,000 and 40,000 women registered to vote in Indianapolis alone within a few months. However, Indiana suffragists soon suffered a bitter disappointment. On October 26, 1917, the Indiana Supreme Court ruled the law was unconstitutional.

The court’s decision shocked Edwards, but she declared that Indiana women would continue to fight for equal enfranchisement. She was right. Although the women of the state seemed shaken by the setback, they soon recovered, gaining confidence as momentum for a national suffrage amendment mounted.

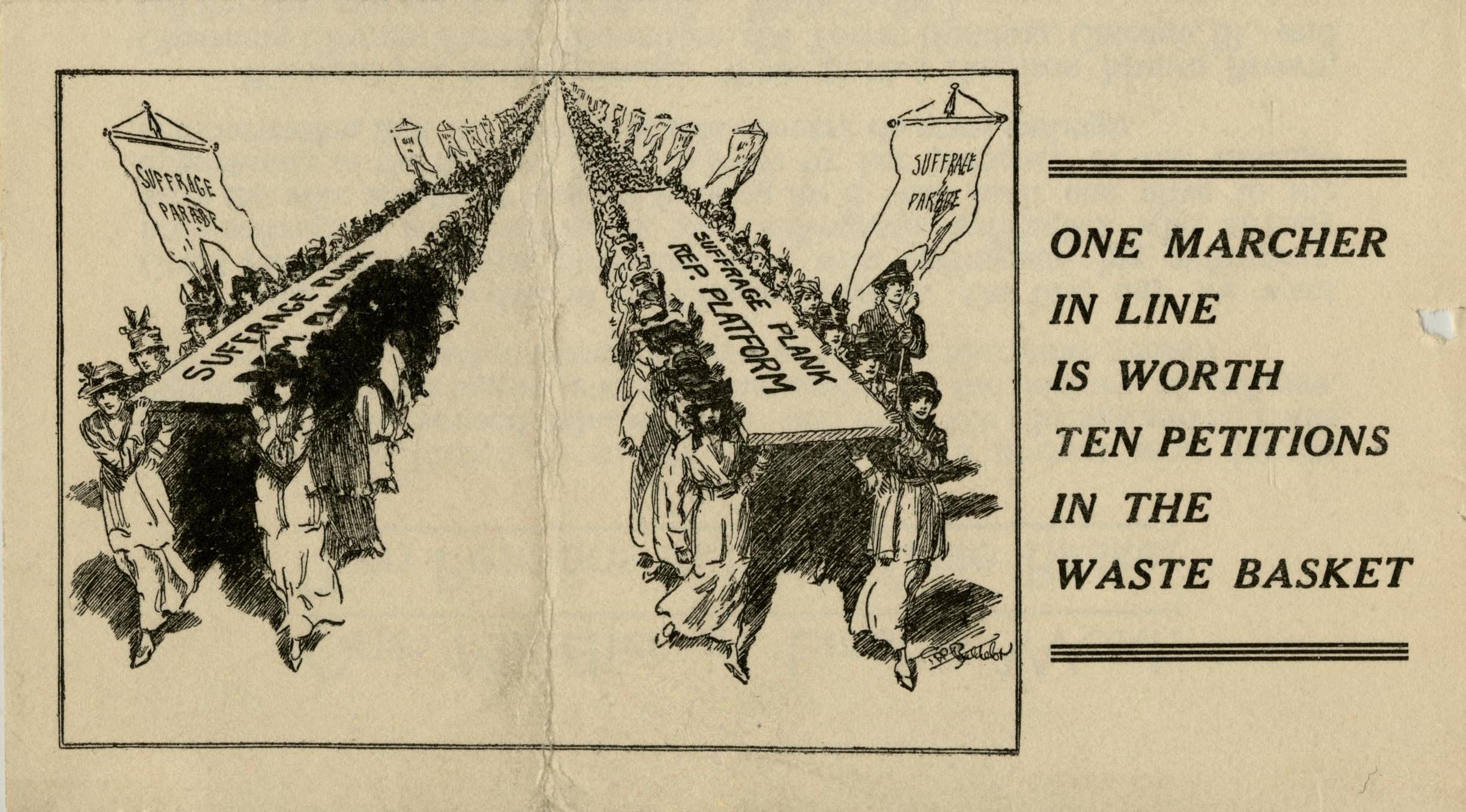

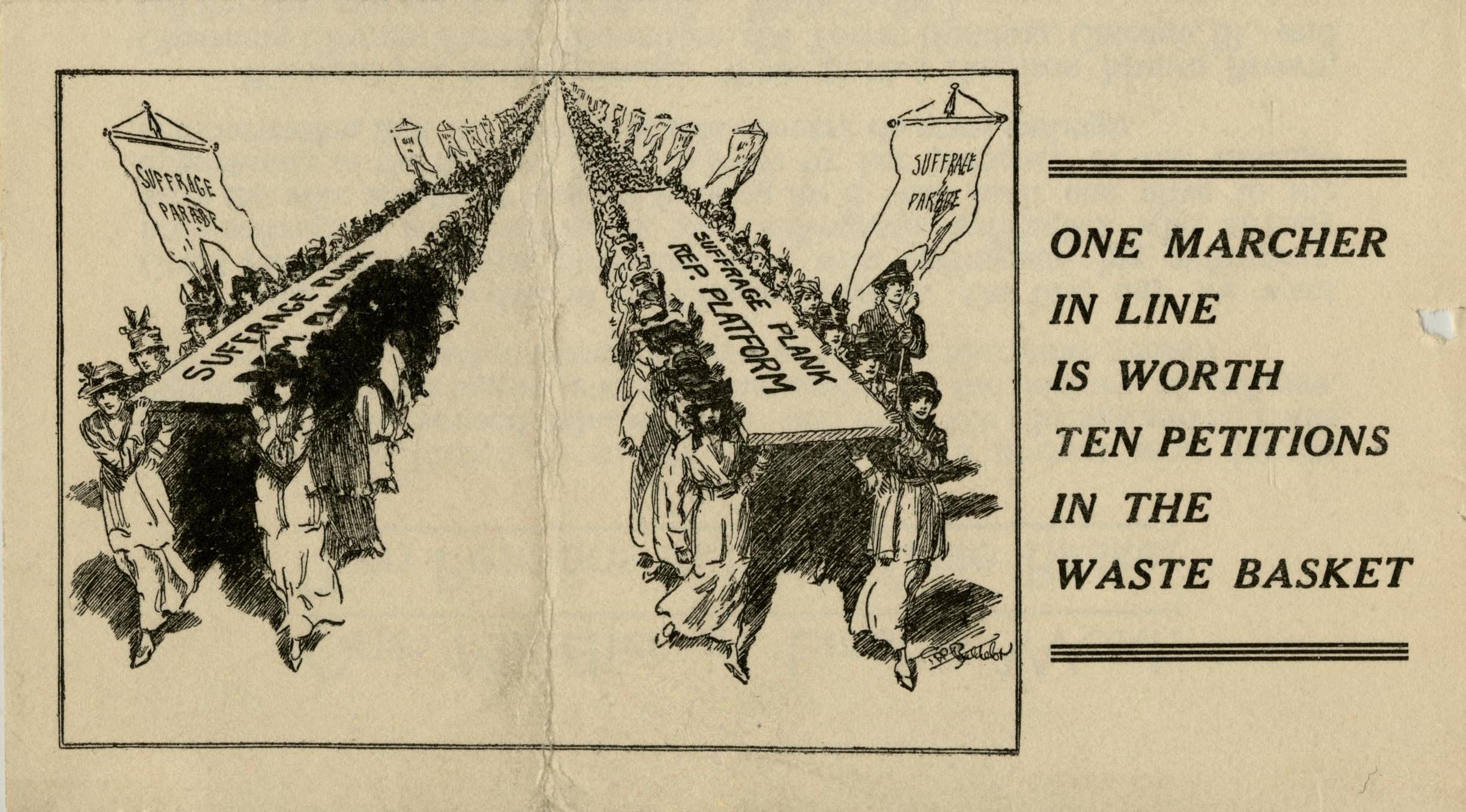

Cartoon from NAWSA leaflet promoting pro-suffrage parades in Chicago and St. Louis, 1916. (S3355)

While managing her husband’s chair factory during his war service, Edwards also served as the Franchise League’s president until 1919, when she became more heavily involved with NAWSA working for the passage of the 19th Amendment. The Susan B. Anthony Amendment, as it was then called, was ratified on August 18, 1920. It stated, “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex.”

Carrie Chapman Catt and Marie Stuart Edwards on either side of the next U.S. president, Warren G. Harding, Social Justice Day, October 1, 1920, Marion, Ohio. (SP021)

In February of 1920, months before the amendment’s passage, Edwards helped found the League of Women Voters, in preparation for helping women exercise their new rights as voting citizens. A non-partisan organization, approximately 2 million women joined the League by 1921. Edwards served as the first treasurer of the National League of Women Voters and then as the organization’s first vice president until 1923. As part of her duties as treasurer and manager of the national speakers bureau for the League, she traveled widely across the United States.

Marie Stuart Edwards (front row, middle) volunteering with the Red Cross during World War II. (SP021)

In Indiana, Edwards remained heavily invested in civic responsibility. She was the first woman to sit on the Peru Board of Education and in 1922, Governor Warren T. McCray appointed her to the Indiana State Board of Education. Later, Edwards led the local Works Progress Administration board in Miami County during the Great Depression. In 1937, she served as vice president of the Indiana Board of Public Welfare, as well as chairman of the drafting committee for the Indiana Civil Service bill. Edwards was also a member of Miami County Board of Public Welfare (late 1940s-1955) and served on state women’s prison parole board during the 1950s. She died in Peru, Indiana on November 17, 1970.

Sources:

Wilson, Mindwell Crampton. “Thoughts in Passing.” Carroll County Citizen-Times, November 17, 1917, 3.

Dice, Nellie Waggoner. “Forum: The Readers Corner.” Indianapolis Star, July 16, 1977, 63.

Harper, Ida Husted, ed. “Indiana.” In History of Woman Suffrage, 1900-1920, vol. 6. New York: National American Woman Suffrage Association, 1922.

Kalvaitis, Jennifer M. “Indianapolis Women Working for the Right to Vote: The Forgotten Drama of 1917.” MA thesis, Indiana University, 2013.

Images from the Mary Smiley Small Photograph Collection (SP021) and Women’s Suffrage Movement Collection (S3355), Rare Books and Manuscripts, Indiana State Library. These items are available online in Women in Hoosier History collection in the ISL Digital Collections.

This blog post was written by Rare Books and Manuscripts Librarian Brittany Kropf. For more information, contact the Rare Books and Manuscripts Division at (317) 232-3671 or “Ask-A-Librarian.”