The Indiana Colonization Society, formed 1829 and based in Indianapolis, advocated for the relocation of free people of color and emancipated slaves in Indiana to settlements in Liberia, Africa. The ICS was an auxiliary of the American Colonization Society, located in Washington, D.C., which formed in 1817.

Premised on the idea that an integrated society was impractical and impossible, “colonizationists,” who were overwhelmingly white, argued that black people could find liberty only in Africa. A small portion of free people of color who agreed that justice, liberty and prosperity could not be achieved in America emigrated. Critics, such as free black people and abolitionists, voiced strong opposition to this movement. They asserted that the agenda of the society was counterproductive for racial reconciliation and integration, that it was overall an ineffective scheme to combat slavery and finally that it undermined anti-slavery efforts. Free people of color who wished to “fight against slavery and for equal rights as American citizens” viewed this plan as effectively abandoning those still enslaved. “Abolitionists saw the colonization movement as a slaveholders’ plot to safeguard the institution of slavery by ridding the country of free blacks.” Colonizationists maintained that their motives were benevolent and philanthropic, but even supporters questioned whether the idea of relocation was even practically feasible or financially realistic.

In the 1820’s and 1830’s, the movement gained support in the state legislature and with citizens throughout the state, but by late 1830’s interest and activity declined. Black Hoosiers opposed it vehemently, resolving at an 1842 convention that, “we believe no well-informed colonizationist is a devoted friend to the moral elevation of the people of color.” The ICS reacted with renewed efforts for the movement when, in 1845, the Rev. Benjamin T. Kavanaugh was named as its agent. He was tasked with raising awareness, organizing supporters and local auxiliaries, fundraising and emigrant recruitment. By 1848, the Rev. James Mitchel, a Methodist minister, abolitionist and colonization advocate, took over as agent and secretary of the American Colonization Society of Indiana. Both Kavanaugh and Mitchell recruited black ministers to raise awareness in the black community and to identify potential emigrants. These men, the Rev. John McKay and the Rev. Willis R. Revels, had limited success. “Revels won approval from black citizens… but soon gave up his post.” Kavanaugh attributed this to pressure from abolitionists. McKay was appointed as, “an agent for the board to purchase land in Liberia and promote colonization among Indiana black citizens.” In the 1850’s he traveled to Liberia with two groups of emigrants and observed the colony, reporting back enthusiastically. Escalating tension between the north and south over slavery, and increasing violence over issues such as the question over expansion of slavery into new territories, led to laws in Indiana that gave free people of color reason to consider emigration, even if the vast majority chose to remain in the country of their birth. During the period of the 1830s until the 1850’s, according to Anthrop, “increasing tensions nationally between anti-slavery and slavery factions… resulted in increasing prejudice against blacks. The culmination of this prejudice in Indiana was Article XIII of the Indiana Constitution of 1851,” which prohibited blacks and mulattoes to enter or settle in the state. Fines set for violation were appropriated to “defray costs of sending blacks in Indiana to Liberia.” Further legislation, “required all blacks already living in Indiana to register with the clerk of the circuit court.”

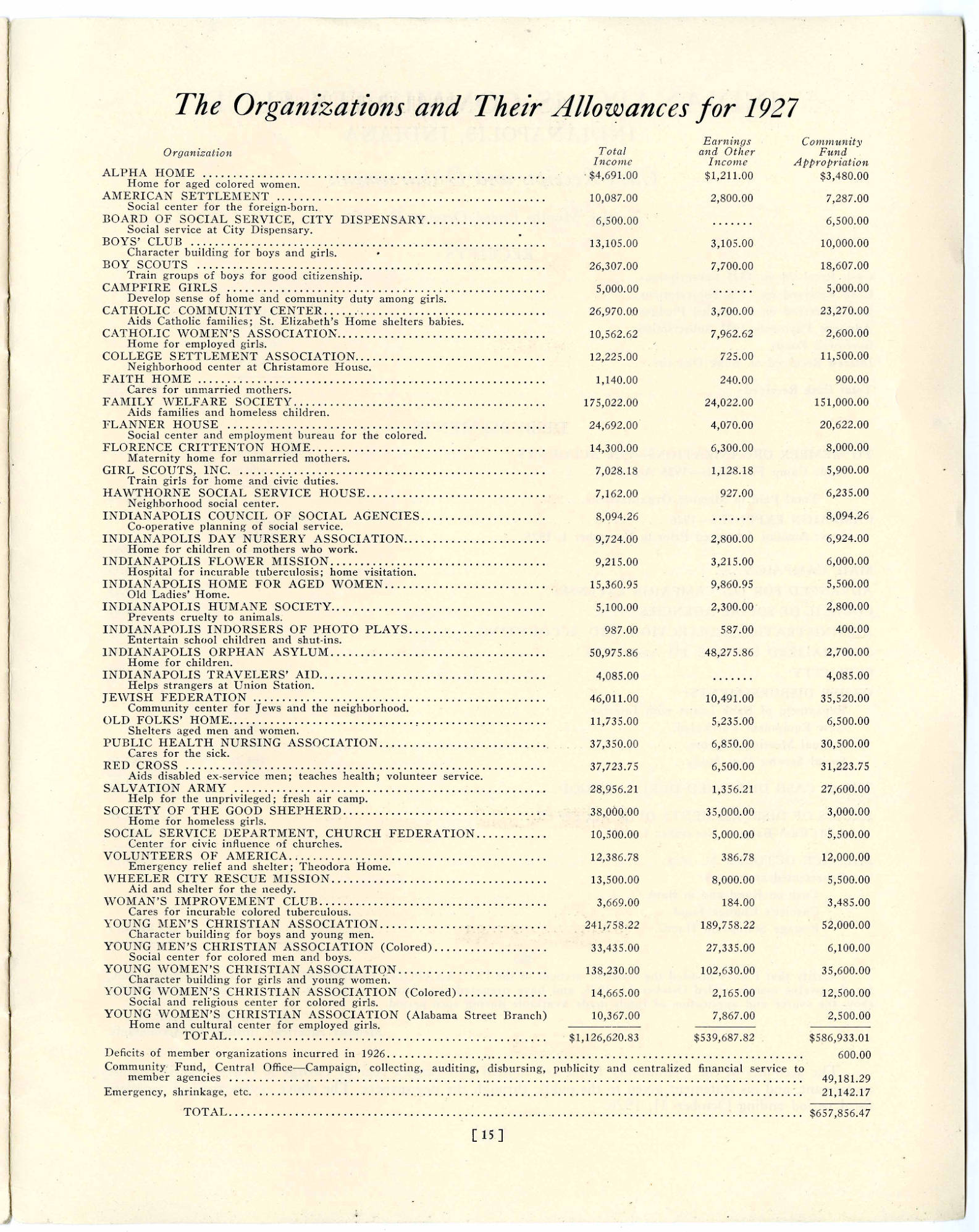

In 1852, ICS advocacy led to a state initiative when the Indiana General Assembly formed the Indiana Colonization Board and began providing funds to help, “Indiana free blacks emigrate to Liberia on the western coast of Africa.” The state government appropriated funds to finance the purchase of land in Liberia and for the transport and support of immigrants. According to Anthrop, “eighty-three” free people of color emigrated from Indiana to Liberia, but the state board facilitated the departure of “only forty- seven” of those emigrants. During the 1840’s, 1850’s and 1860’s advocates and critics within the movement and the government squabbled over complaints about financial arrangements, funding cuts, fundraising methods, settlement location and administration and over negotiations with the government of Liberia. James Mitchell, in an 1855 “Circular to the Friends of African Colonization” apprising society members of the progress and obstacles faced by the movement, admitted the paltry sum of $65 per person for emigration was insufficient to provide for transportation, and offered nothing for support or protection of immigrants. In the final report in 1863 to the State Board by its secretary, the author William Wick, concluded that the movement had been a “total failure.” Wick attributed this failure to the ambition of formerly enslaved people to be equal in social status to white Americans.

The types of records in the sub collection of the Colonization movement include government documents, such as the report to the State Board of Colonization, organization records, such as Indiana Colonization Society reports, circulars that act as newsletters to supporters, private society correspondence disseminated to influential political operatives and the society’s monthly publication The Colonizationist, as well as a campaign literature from the 1860 race for the governorship of Indiana in a the form of speech by Oliver P. Morton. These materials offer insight into the theoretical and philosophical tenets of the Colonization movement, document its efforts, successes and obstacles, provide historical context and can be used to map out its historical trajectory from a burgeoning movement to abject failure. Scholars and students will find these items to be a rich resource for exploring the history of the Back-to-Africa movement. Genealogists and historians will find in these primary sources a wealth of information on the individuals active in this movement, and on those who ultimately emigrated to Liberia.

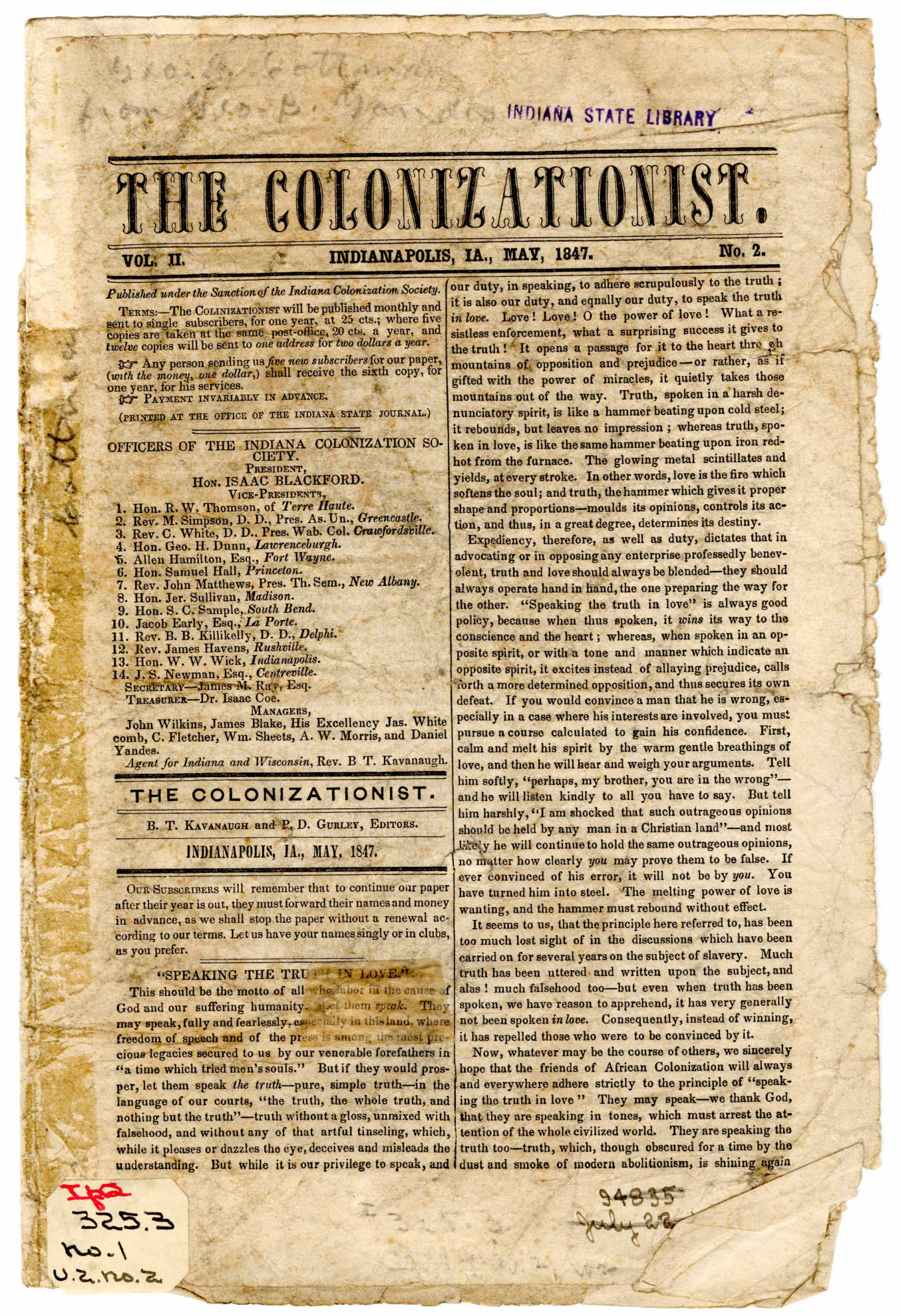

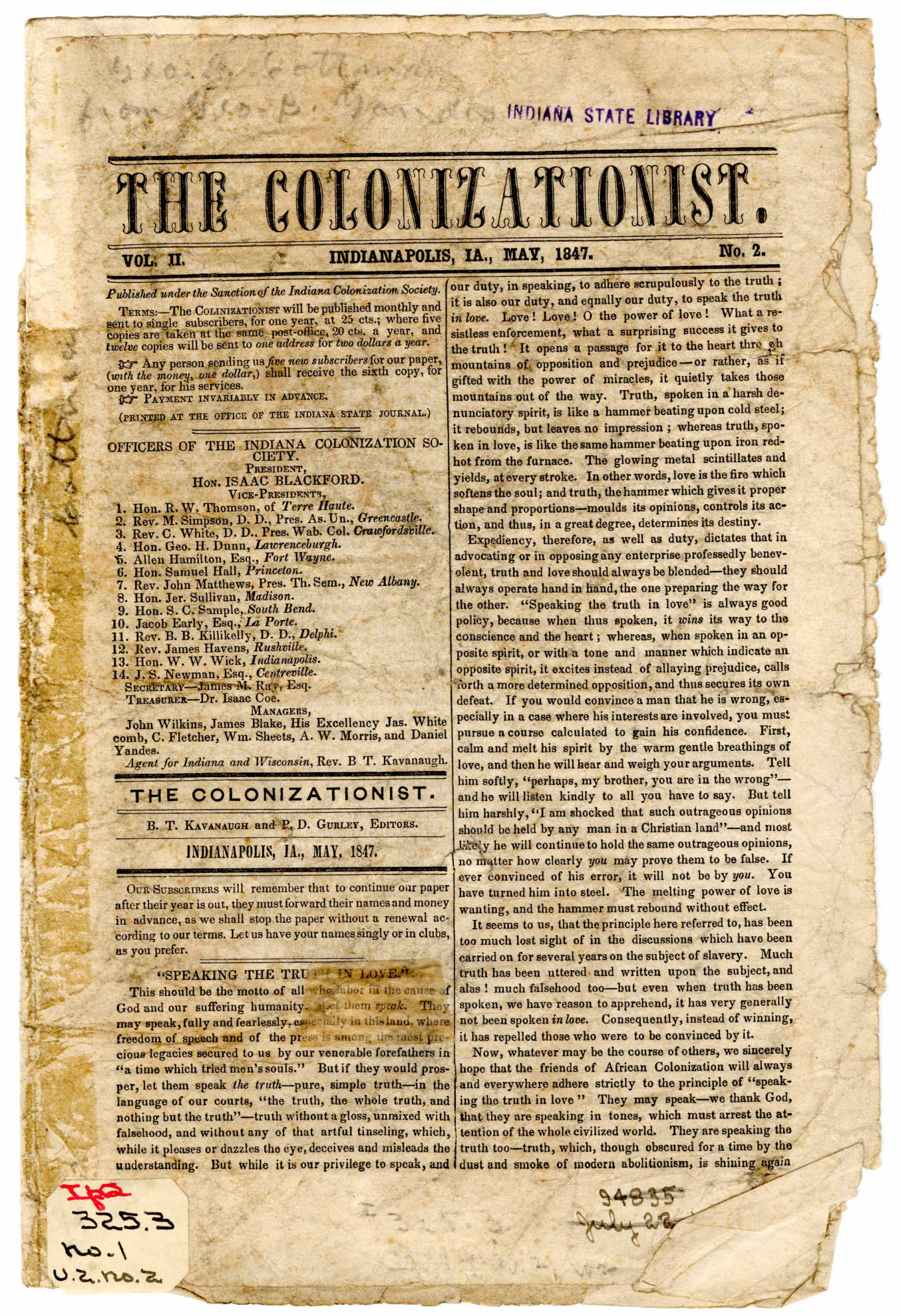

Colonizationist May 1847, vol. 2, no.2

ISL_IND_Pam_Coloniz_1847

The Colonizationist, owned by John D. Defrees, was the monthly publication of the Indiana Colonization Society and was printed by the Indiana State Journal in Indianapolis. The ICS, formed in 1829 and based in Indianapolis, advocated for the relocation of free people of color and emancipated slaves to settlements in Liberia, Africa. The publication was edited by B.T. Kavanaugh and P.D. Gurley. Kavanaugh was a Methodist minister and the agent of the ICS. Gurley, who was the minster of the First Presbyterian Church of Indianapolis from 1840-49, and again in 1859, was appointed the Chaplain of the United States.

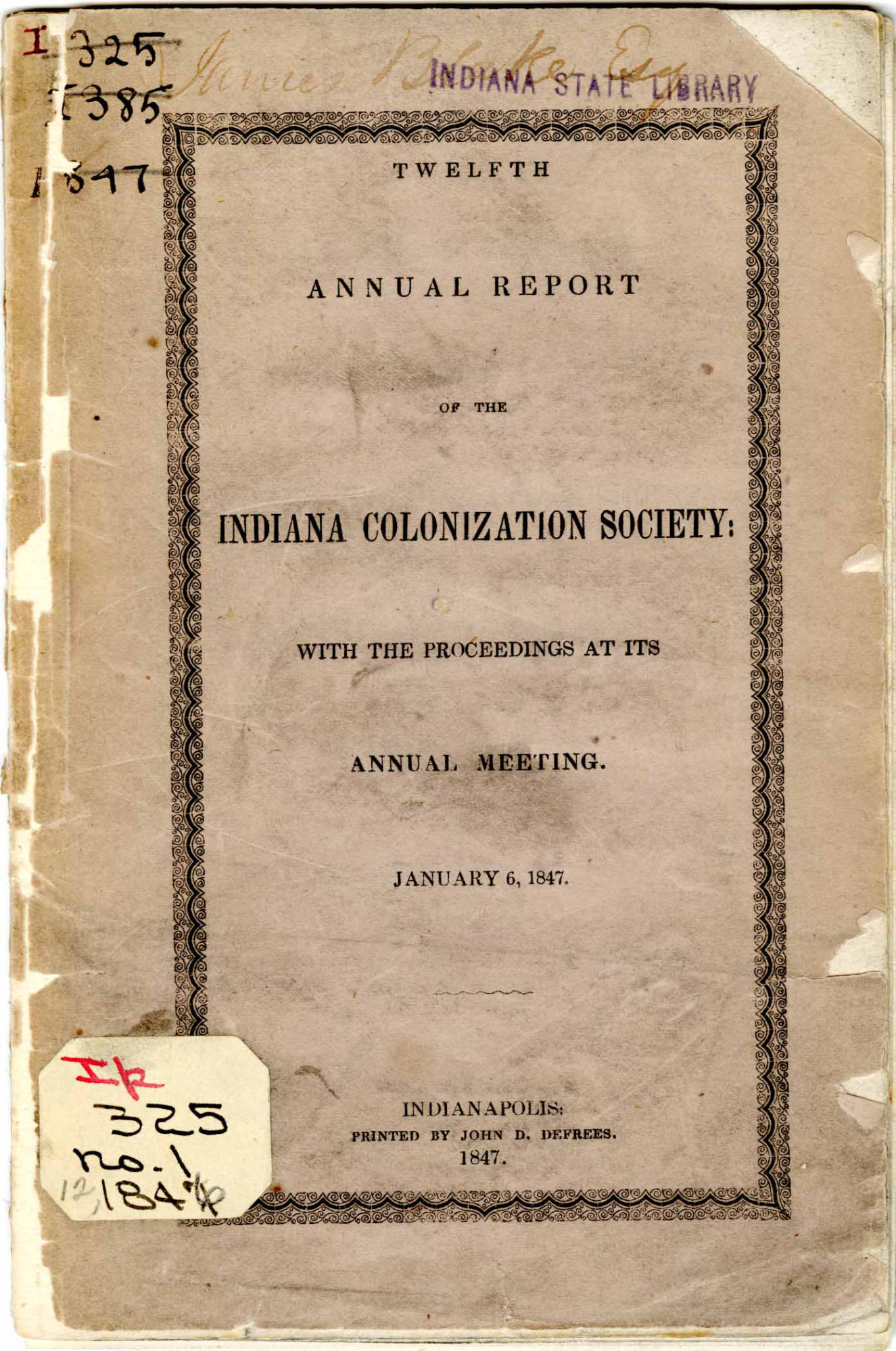

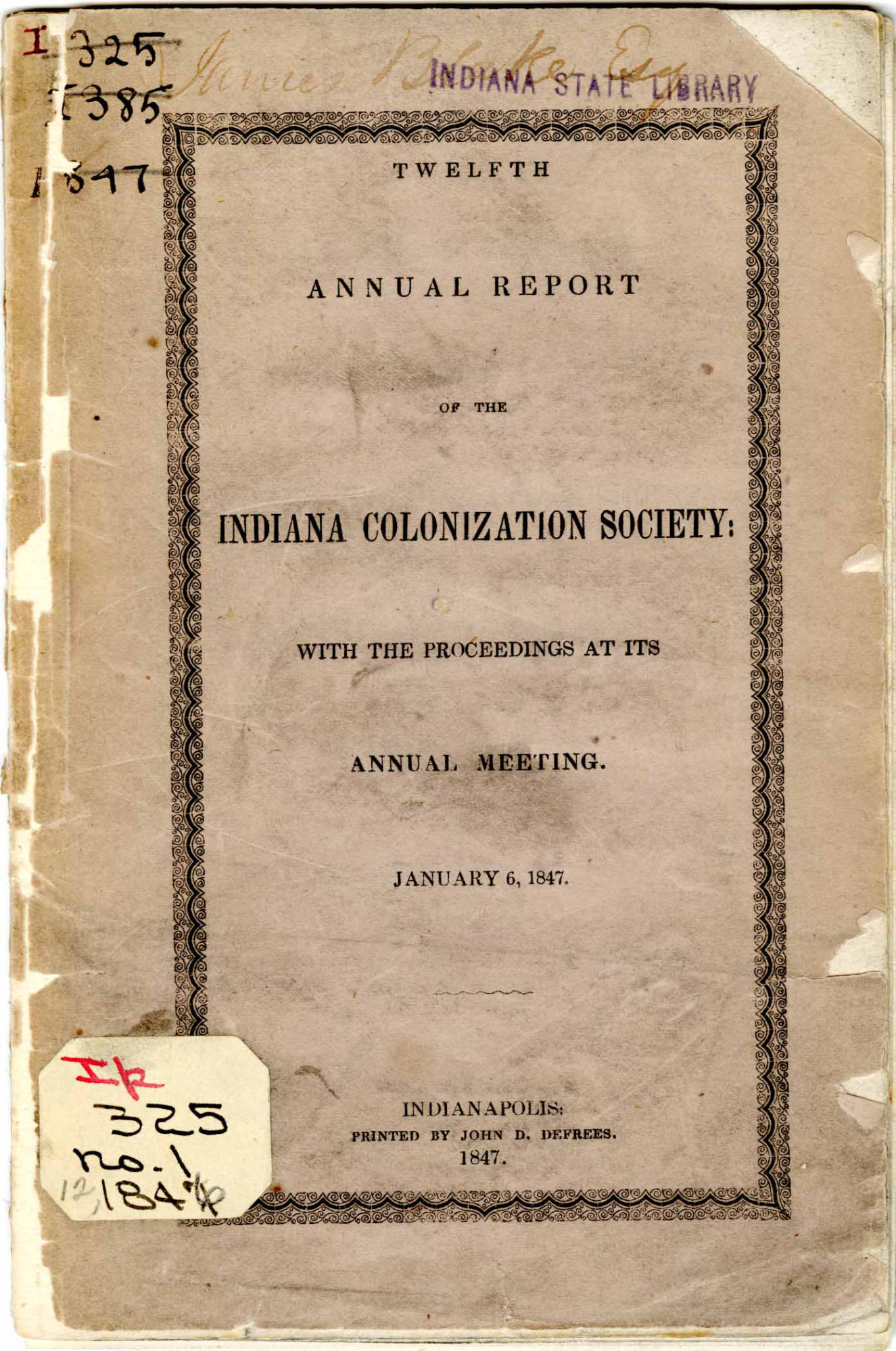

Twelfth Annual Report of the Indiana Colonization Society, 1847

ISL_IND_RptColSoc_1847

Report by the Indiana Colonization Society on the proceedings of its annual meeting held Jan. 6, 1847 at Robert’s Chapel in Atlanta, Jackson Township, Hamilton County, Indiana. This report includes the meeting minutes which describe the proceeds of the event, such as topical addresses and speeches given, motions made by members and resolutions adopted by the society. It also includes detailed financial proposals and cost estimates for the scheme, statistics on the organization’s success, lists of ships with the ship name and year of passage from 1843-46, and an overview of the national organization’s statistics. The official publication, The Colonizationist, and the individual efforts of members, such as the Rev. B.T. Kavanaugh are discussed. An appendix lists “twenty reasons for the success of Liberia.”

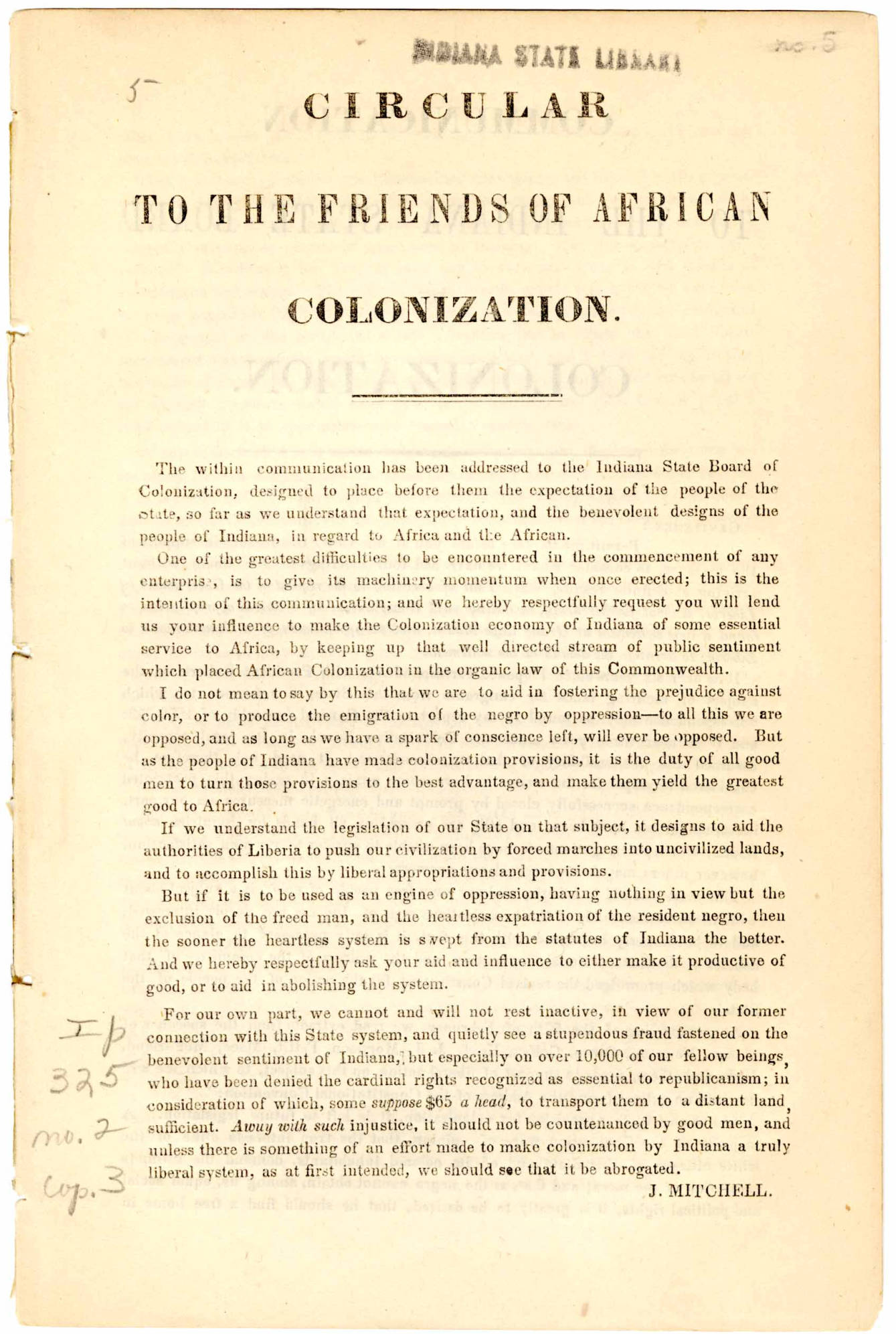

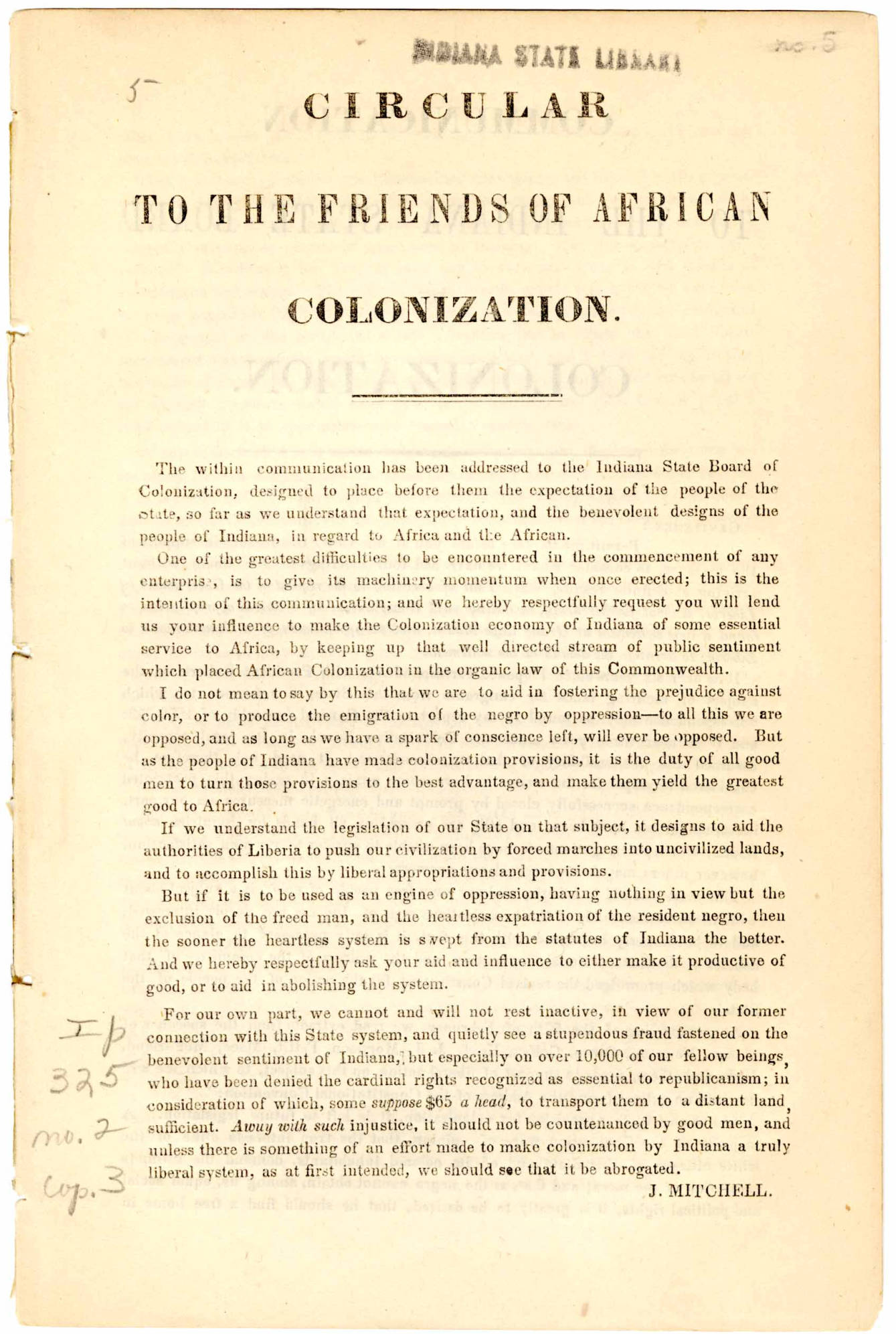

Circular to the Friends of African Colonization

ISL_IND_Pam_Mitch_CirAfCol

This 1855 circular is addressed to the Friends of African Colonization. It is comprised of a one page introduction and a long letter addressed to the Indiana State Board of Colonization. The author, the Rev. James Mitchell was the Secretary of the American Colonization Society of Indiana. In the circular, he lists reasons for inaction of the board in the past, legislative, financial and administrative obstacles faced, and lays out a detailed plan for action.

Letters on the Relation of the White and African races in the United States, and the Necessity of the Colonization of the Latter

ISL_IND_PAM_LtrsColMov1860

This pamphlet is a collection of private letters written by James Mitchell as agent of the Indiana Colonization Society, on the subject of the African Colonization movement, detailing the actions, policies and theoretical foundation of the organization. It is addressed to the candidates for the 1860 U.S. presidential election. Mitchell seeks to privately communicate the aims of the movement to popular leaders and the future president. The correspondence includes an extract from the 1852 report to the legislature of the state of Indiana titled, “The Separation of the Races Just and Politic,” an 1857 letter from Mitchell to President James Buchanan and an 1849 letter to President Zachary Taylor.

The Speech of Oliver P. Morton, the Republican candidate for Lieutenant Governor, 1860

ISL_IND_Pam_Mort_Spch_1860

This is a speech by Republican candidate for Lieutenant Governor of Indiana, Oliver P. Morton, delivered in Terre Haute on March 10, 1860. The speech discusses campaign issues, such as popular sovereignty, the expansion of slavery into new territories, “sectional parties,” John Brown, the fugitive slave law, hostility between north and south, abolition, tariffs and homesteading legislation. Morton and his running mate won the election of 1860, with Lane opting to take a seat in the Senate, Morton became the 14th Governor of the state of Indiana.

Report on colonization for 1863 to the state board

ISL_IND_Gov_SBC_Rpt_1863

This 1863 report on the Colonization movement is authored by the Secretary of the State Board of Colonization William W. Wick. It is addressed to the Colonization Board, but is intended for all members of the legislature and the public. Wick writes to report the “total failure” of the Colonization movement.

References

Anthrop, M. (March 2000). Indiana emigrants to Liberia. The Indiana Historian, March 2000. Indiana Historical Bureau.

Retrieved from https://www.in.gov/history/files/inemigrants.pdf.

Notes on other resources

The American Colonization Society Collection at the Library of Congress – letters from Indiana emigrants

American Colonization Society Collection

http://www.loc.gov/rr/print/coll/007-b.html

American Colonization Society records, 1792-1964

https://lccn.loc.gov/mm78010660

This blog post was written by Ricke Gritten, Indiana Division intern at the Indiana State Library.