If you’ve ever accidentally kept a stack of books for an extra week, or needed an additional few days to watch a borrowed DVD, you’ve felt the pinch of the resulting library fines. While fines might be as little as a dime a day for a book, they seem to accrue exponentially. Not only are fines an annoyance, but they can be a legitimate barrier to service. Every day at circulation desks across the state, public library users are denied borrowing privileges, sometimes years after accruing fines, because of balances owed for overdue or long-lost items.

There are many reasons patrons acquire fines. For some, it’s simple forgetfulness. For others, it’s a larger issue stemming from life circumstances like a lack of transportation, work schedules or changes in housing. For example, when moving between families, foster children may forget to return borrowed books from their previous library. Or when packing up and leaving a precarious living situation, people may need to leave their library materials behind.

There are many reasons patrons acquire fines. For some, it’s simple forgetfulness. For others, it’s a larger issue stemming from life circumstances like a lack of transportation, work schedules or changes in housing. For example, when moving between families, foster children may forget to return borrowed books from their previous library. Or when packing up and leaving a precarious living situation, people may need to leave their library materials behind.

What if there was a way for library users to start over from scratch? Or what if there was more leniency for people who needed to keep books an extra week or so? Luckily, over the past years, there has been a nationwide push toward eliminating library fines, and the push isn’t only coming from library users, but the librarians themselves.

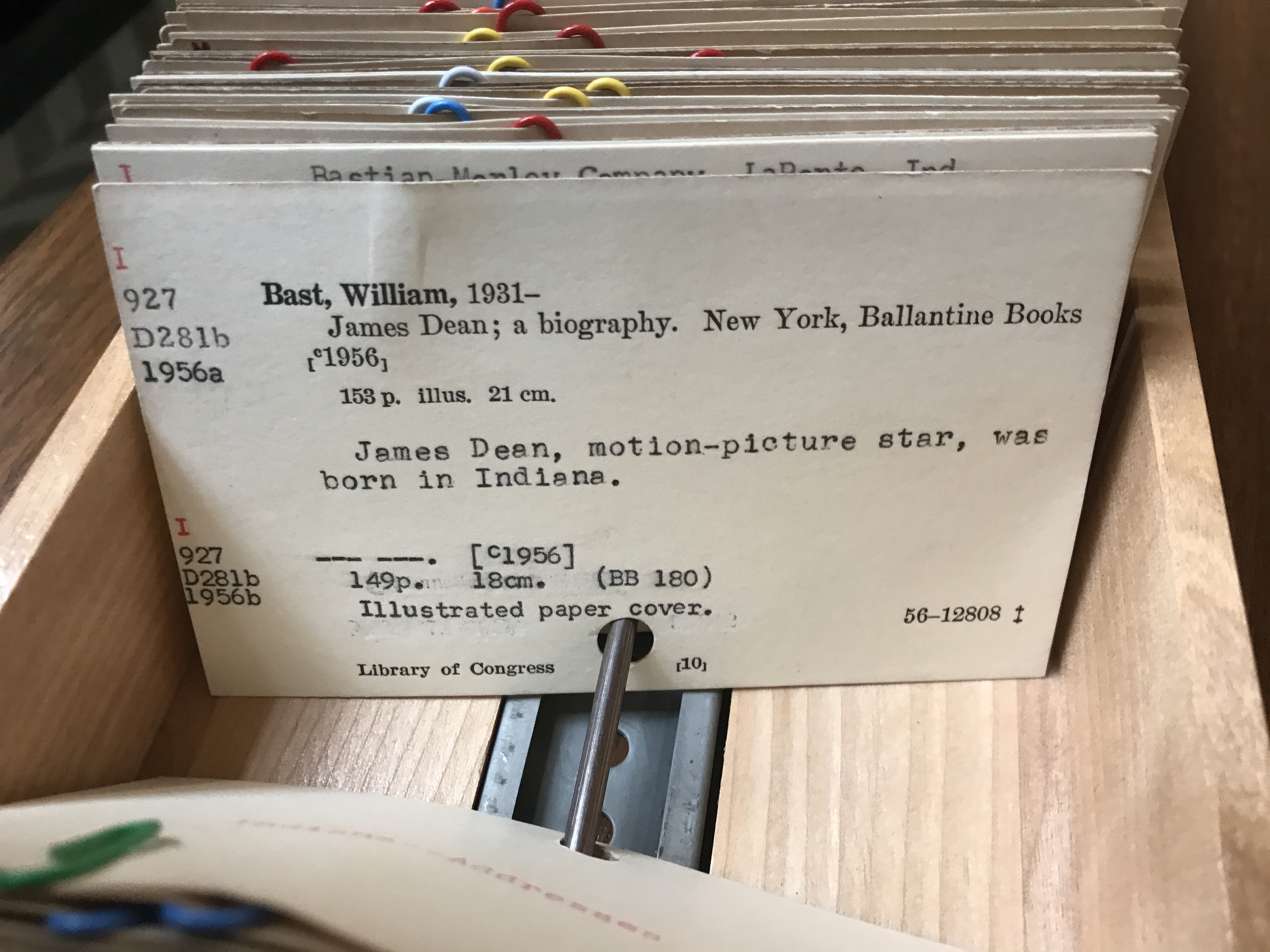

In Indiana, over 20 public library systems have opted to go fine free. This includes but is not limited to: Kendallville Public Library, Evansville Vanderburgh County Public Library, West Lafayette Public Library, Monroe County Public Library, Vigo County Public Library, Owen County Public Library, Morgan County Public Library, Anderson Public Library and more. Many more library boards are considering the move, especially after the Chicago Public Library boldly made the move in October 2019. The Indianapolis Public Library recently stated that in an effort to provide equitable service they are suspending the accrual of all fines and fees until further notice. Each library’s policy varies, and some fees may still exist for extremely overdue, damaged, or lost items, so please check with your local library for more details.

But don’t libraries need the money? While the public might perceive library fines as a major source of income for the library, they’re not. In Indiana, about 87% of a library’s budget comes from local sources like property taxes.1 Of the nearly $400 million in total revenue Indiana libraries received in 2019, only $6 million – about 1.5% – was received from fines and fees. Additionally, many systems have practiced writing off “uncollectable” fines over the years. At times, the cost of recovering materials or lost items can cost more than the materials are worth in staff time and collection service fees. Losing materials has always been a cost of doing business.

But don’t libraries need the money? While the public might perceive library fines as a major source of income for the library, they’re not. In Indiana, about 87% of a library’s budget comes from local sources like property taxes.1 Of the nearly $400 million in total revenue Indiana libraries received in 2019, only $6 million – about 1.5% – was received from fines and fees. Additionally, many systems have practiced writing off “uncollectable” fines over the years. At times, the cost of recovering materials or lost items can cost more than the materials are worth in staff time and collection service fees. Losing materials has always been a cost of doing business.

Some opponents to the fine-free library movement believe that fines and due dates teach “responsibility,” and not having them will encourage patrons to ignore due dates and hoard library materials. What some libraries are finding is the opposite. When fines are eliminated, not only are older materials are being recovered, and most items are still coming back before they are considered lost.

As a patron, what should you do if you have a large amount of library fines, but your library hasn’t eliminated fines? Try reaching out to the director or circulation manager at your library. While each library’s policy varies, some libraries offer the ability to reduce or waive fines and lost book fees in some situations. Some libraries periodically offer “amnesty” weeks where the fines on any books returned are forgiven. Some even offer opportunities to pay down fines with canned good donations or by tracking time read to “read off fines.” Some libraries write fines off as uncollectable over time, so the fines you thought you owed may have already been eliminated years ago. Please don’t let the $17 in fines you racked up in 1993 deter you from checking out all that’s happening in today’s public libraries.

1. 2018 Indiana Public Library Annual Report

This post was written by Jen Clifton, Library Development Office, Indiana State Library.