As a conservator, I have had many people ask me why conservation and preservation programs are funded “since we have digitization”. While it is a common misconception that digitization is “forever”, many people also do not realize that there are often times when collections materials must undergo conservation treatment before they are digitized. Some items are just far too fragile or unstable to survive the process.

Here at the Indiana State Library, I recently performed treatments on two special newspapers from our collections that had been selected for digitization and upload to the Hoosier State Chronicles database. Before treatment, I discussed these issues of Indiana Gazette with Chandler Lighty, the Project Manager of Hoosier State Chronicles, who explained just how rare and historically important they are:

“In 1804, Elihu Stout moved to Vincennes to publish the laws of the Indiana Territory. Stout also printed the first newspaper in the territory, the Indiana Gazette on July 31, 1804. He published the paper until April 12, 1806. Shortly thereafter a fire destroyed his press. No copy of the first issue of the Gazette is known to exist. Original issues of the Gazette are scarce, and are preserved at repositories across the country including the American Antiquarian Society, Harvard University, and the University of Texas-Austin. The Indiana State Library is fortunate to house two original issues of the Gazette from February 15, 1806, and April 12, 1806. These two issues are not very remarkable for their content, which was primarily eastern U.S. and European news. Aside from their advanced age, they are most remarkable for their purpose. When Stout first published the Gazette, he helped create a literate and informed public in Indiana over 200 years ago. After losing his press, Stout re-established a newspaper over a year later, which he titled the Western Sun.”

My first inspection of these important, historical newspapers revealed that they shared similar issues, despite being printed on two very different kinds of paper: creasing, heavy surface dirt, acidic discoloration from the aging process of the paper, tears and losses, and a lot of fly specs (a polite term used in conservation for “fly poop”).

Starting with surface cleaning, I then moved on to removing the fly specs. Removing fly specs is a meticulous business involving scalpel blades, a microscope, and a steady hand.

Microscope image of the removal of fly specs with scalpel (Indiana Gazette, No. 20, of Vol. 2, April 12, 1806, Indiana State Library Newspapers Collection)

The removal process was very successful, and the papers were much cleaner (and, perhaps, less icky) than before.

In the next phase of treatment, I decided to wash both newspapers. The issue from April 12, 1806 (No. 20 of Vol. II) was suffering from a lot of acidic discoloration as well as very large tide lines where the paper had previously suffered some water damage. The other issue, from February 15, 1806 (No. 14 of Vol. 2), had several areas with smaller tide lines as well as residue stains (possibly from an adhesive). Washing paper as a conservation treatment is very controlled and involves several techniques that professional conservators have been trained to perform. Do not attempt to wash paper at home! In all cases, all media (such as printing and writing inks, in this instance) and the paper is tested carefully prior to washing to ensure that no inks will run, bleed, strike-through, or fade during the washing process.

After washing and pressing dry, all tears and losses needed to be mended. Conservators often use wheat starch paste as an adhesive because it ages well and can be made thicker for strong adhesion or thinner for adhesion with flexibility. Japanese paper is also the preferred paper for mending in paper conservation because of the way it is made: Japanese paper tends to have longer fibers than western papers, making it possible to use incredibly lightweight papers that still remain strong when mending. After mending, the papers were humidified and pressed one last time before handing them back over to Chandler for digitization.

These images, taken in the Martha E. Wright Conservation Lab here at the Indiana State Library before and after conservation treatment, will give you a better understanding of how conservation treatment improved both the readability of the papers as well as their stability and longevity*.

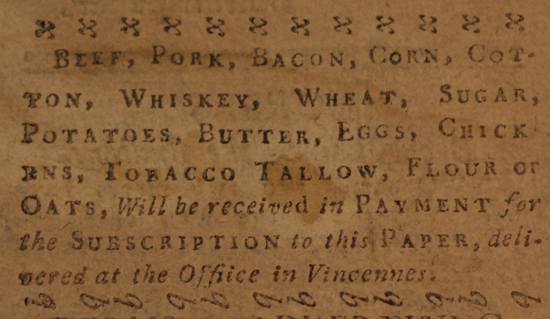

The issues featured above will be uploaded to the Hoosier State Chronicles database soon, where you’ll be able to read the higher resolution versions. One of my favorite parts explains just how many ways you can pay for your subscription:

(Before treatment) Excerpt from Indiana Gazette, No. 20 , of Vol. II, April 12, 1806, Indiana State Library Newspapers Collection

This blog post was written by Rebecca Shindel, Conservator, Indiana State Library.

*Please note that colors presented on computer screens are not precisely accurate, and may look slightly different from one screen to another.