At their core, federal government publications seek to provide information and don’t exactly exist for entertainment purposes. They are not known to have aesthetically pleasing covers or particularly exciting content. Publications are often austere in appearance and the information contained within is both useful and concise. Illustrations exist only if absolutely necessary and when they do, the images are rarely in color.

The cover and inside of a typical Army Technical Manual from 1958 (ISLM p.d. 355 Un58tma TM-11 no. 6665).

One publication that famously resisted the trend of dull and dry content was the magazine known as PS: The Preventative Maintenance Monthly, more commonly known as PS Magazine, or just PS. A publication of the Department of the Army “for the information of all soldiers assigned to combat and combat support units, and all soldiers with organizational maintenance and supply duties,” the magazine was essentially a supplement to the usual Army technical manuals. However, unlike the manuals, PS delivered information in a comic book format, complete with recurring characters, story arcs and full color illustrations.

The eye-catching cover of this issue was drawn by Murphy Anderson and closely resembles that of a superhero comic. (ISLM D 101.87:323).

PS began in 1951 during the Korean War and featured the artwork of former Army Corporal Will Eisner. Prior to his military work in World War II, Eisner had created The Spirit, a popular comic series. Eisner later would write many influential long-form comic books and is credited with coining the term “graphic novel.” The comic book industry’s most prestigious annual awards are named after him.

Eisner helmed PS for many years. In the 1970s-1980s, another well-known artist named Murphy Anderson provided artwork. Like Eisner, Anderson had served during World War II and went on to have a successful comics career, creating artwork for many different titles published by DC Comics.

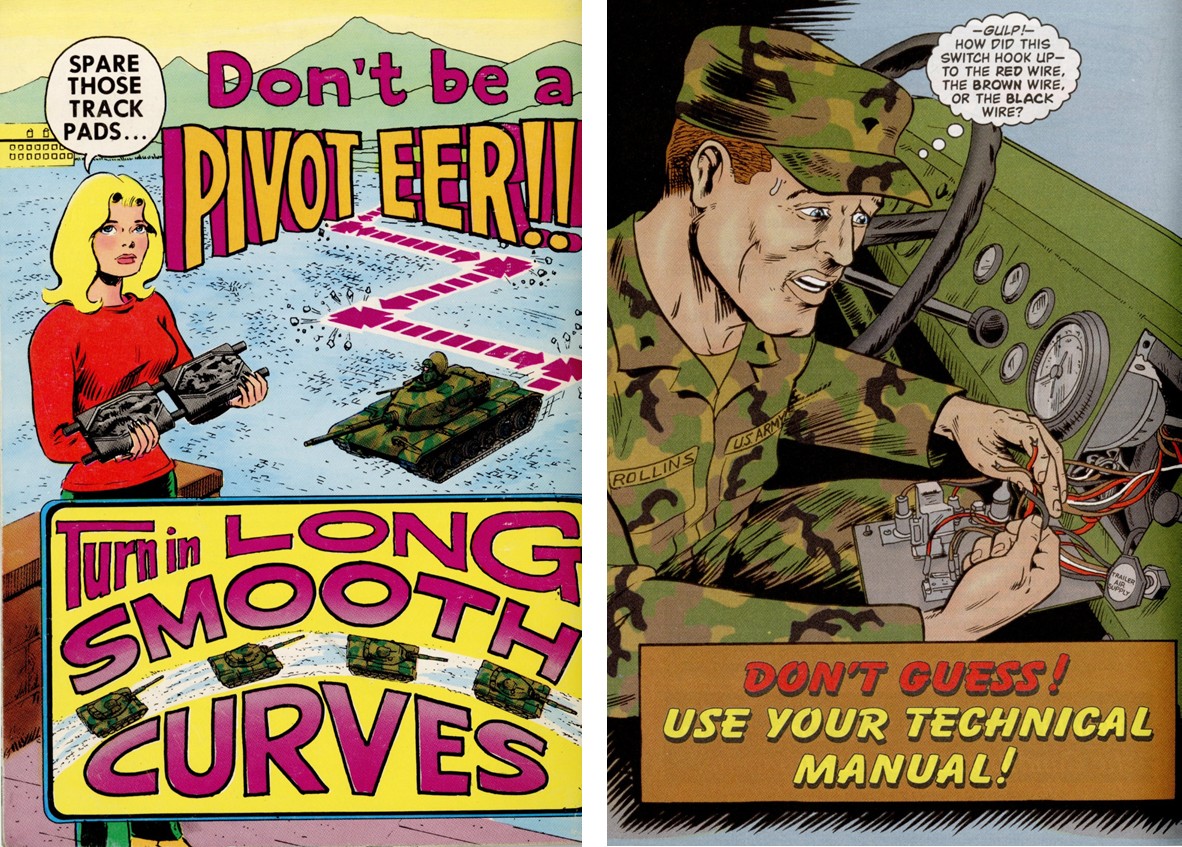

The back covers of each issue featured a full-color preventative maintenance reminder. (Left to right: ISLM D 301.87:341, ISLM D 301.87:545).

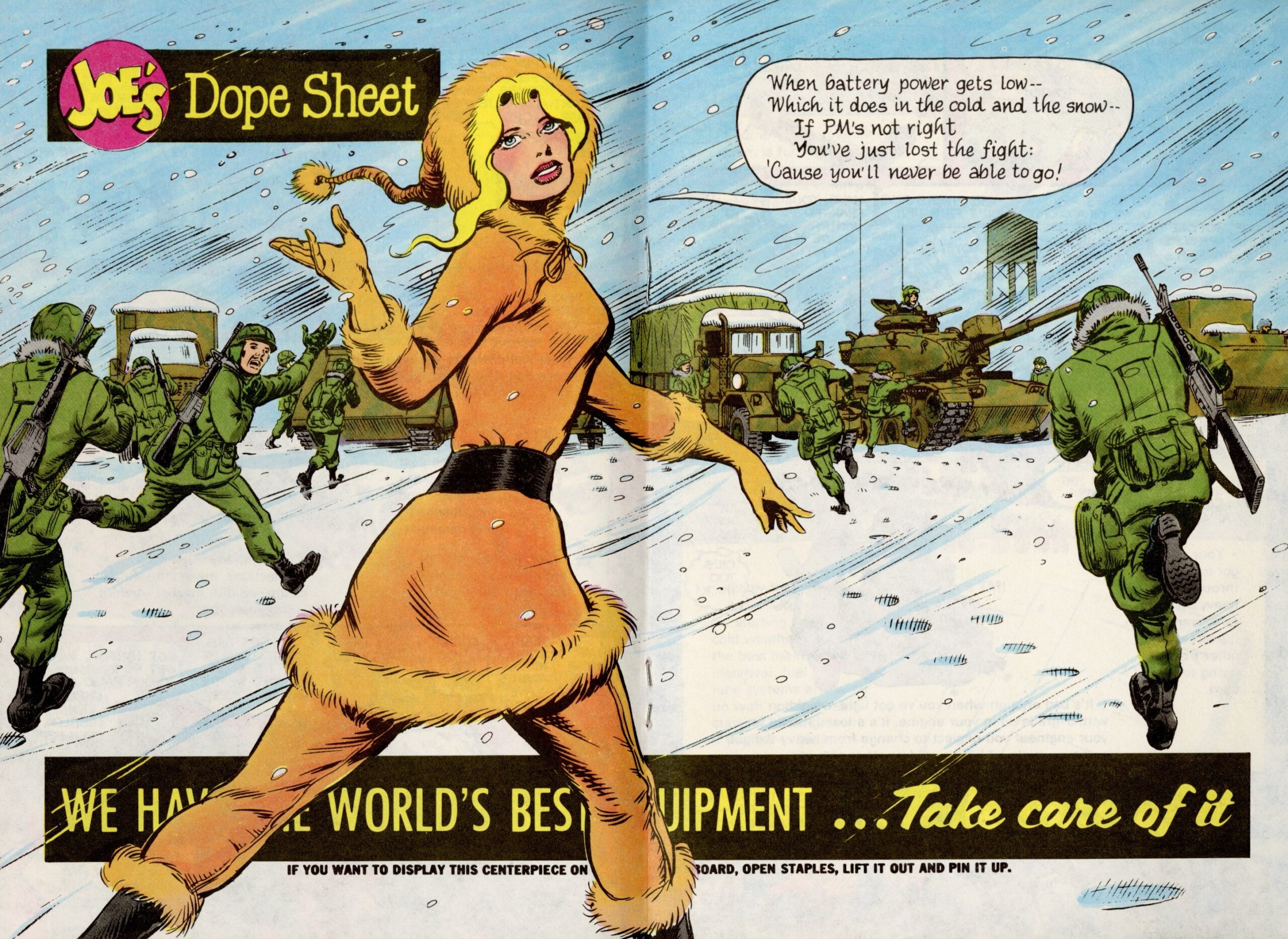

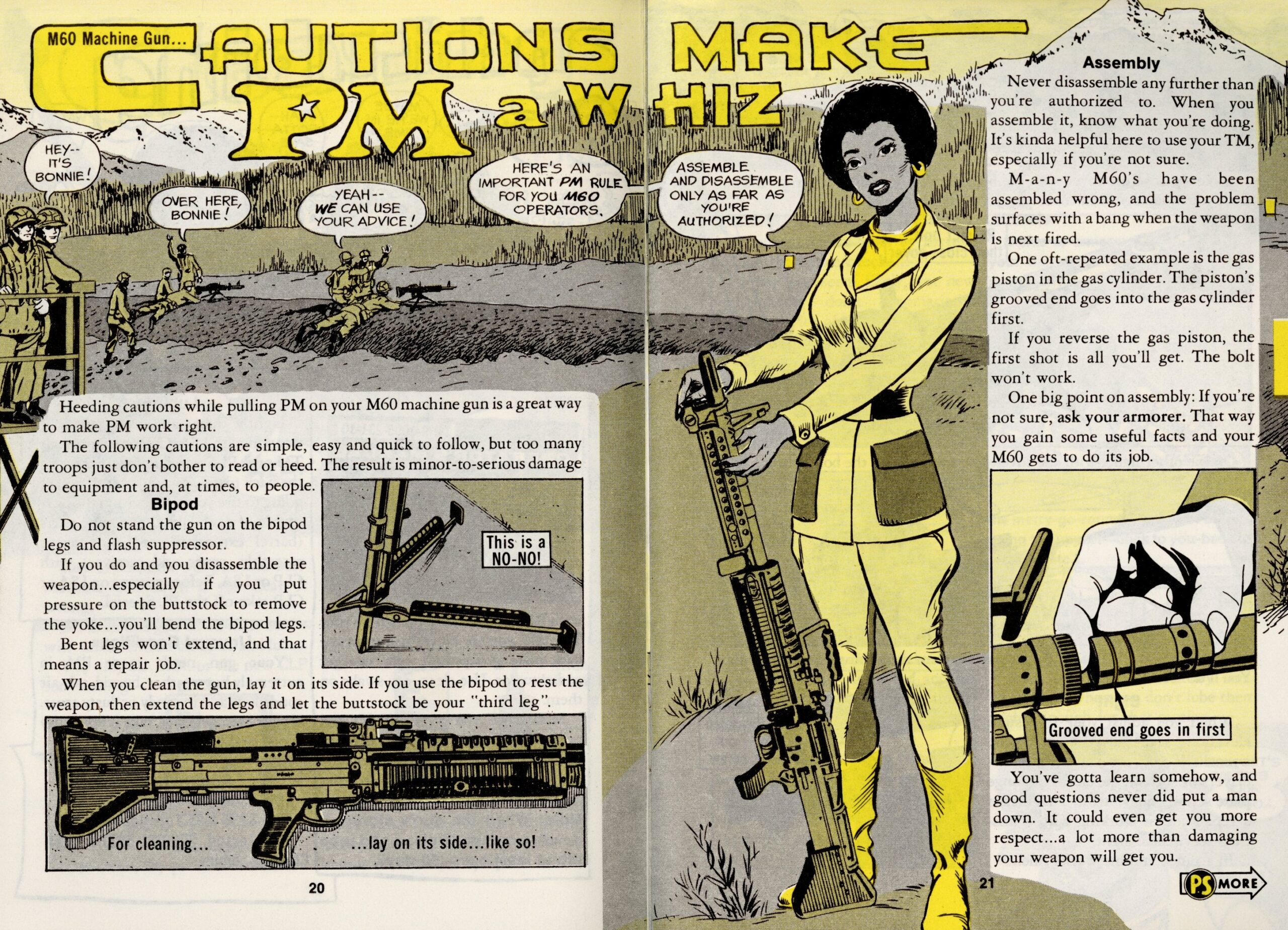

The main message conveyed in each issue of PS was to remind soldiers they had a duty to properly maintain military equipment. Readers were gently chastised on correct procedures by an attractive female civilian character named Connie. In the 1970s, an African American woman named Bonnie was added.

“Joe’s Dope Sheet” was a two-page spread in the center of each issue often featuring one of the comic’s recurring characters. In this example, Connie reminds soldiers to take care of vehicle batteries in cold weather. (ISLM D 101.87:347).

Issues contained short vignettes with illustrated instructions. Here Bonnie demonstrates how to correctly clean an M60 machine gun. (ISLM D 101.87:342).

The military equipment itself became another character in each issue. Military machinery such as tanks and machine guns were often depicted with human physical characteristics like arms and legs and even demonstrated human emotions, to underscore the importance of following proper preventative maintenance.

Anthropomorphizing military equipment was a common component of each issue. In these examples, a bulldozer is sad because its operator doesn’t shift properly and causes unnecessary wear and tear on the transmission while in the accompanying image, an air filter suffers from freezing cold weather. (Left to right: ISLM D 101.87:471, ISLM D 101.87:576).

PS Magazine went completely digital in 2019, and officially ended in 2024 after 73 years of continuous publication. The Indiana State Library has scattered issues from the 1980s through 1999. Digitized versions of back issues are available from several sources, including the University of North Texas Digital Library, the Virginia Commonwealth University Digital Collections and the Internet Archive (1999-2013 only).

This blog post was written by Jocelyn Lewis, Catalog Division supervisor, Indiana State Library. For more information, contact the Indiana State Library at 317-232-3678 or “Ask-A-Librarian.”