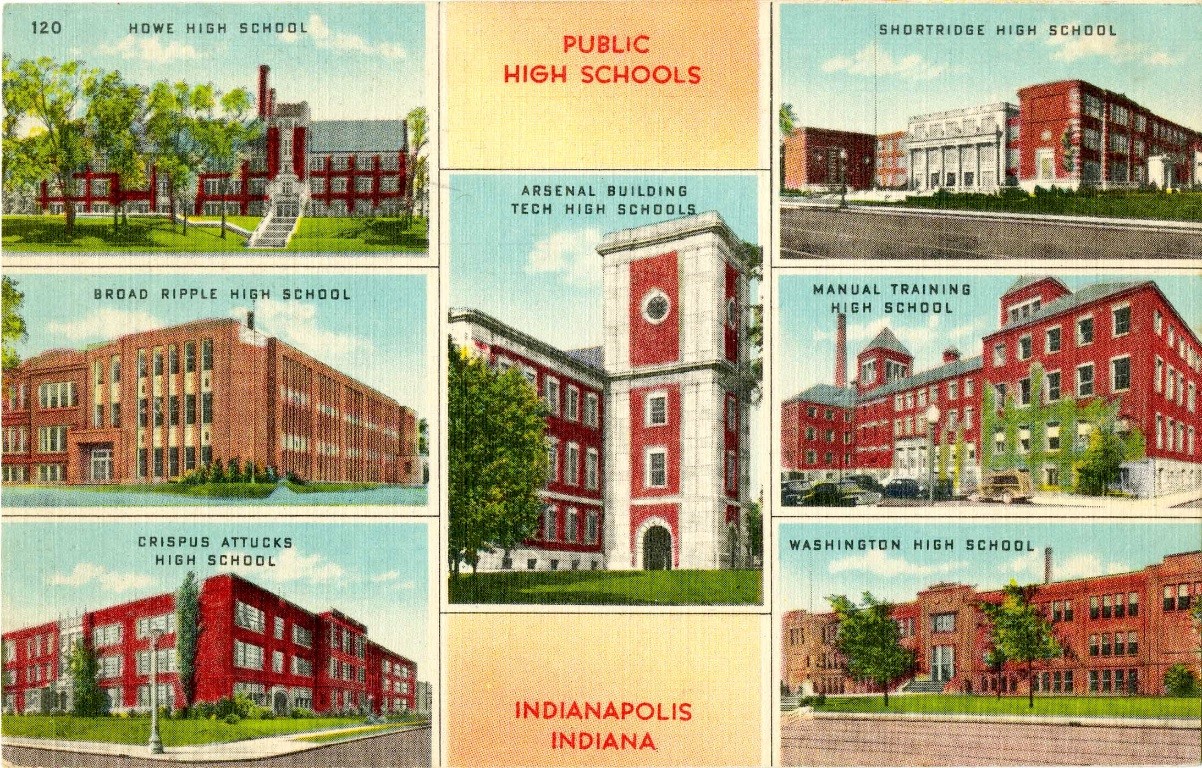

If you are familiar with Indianapolis history, you know that Crispus Attucks High School was the city’s first, and only, all-black high school. But did you know before Crispus Attucks opened, Indianapolis high schools were not formally segregated? Before the fall of 1927, when Crispus Attucks opened its doors, black high school students attended Shortridge, Washington and Arsenal Tech High Schools with white students.

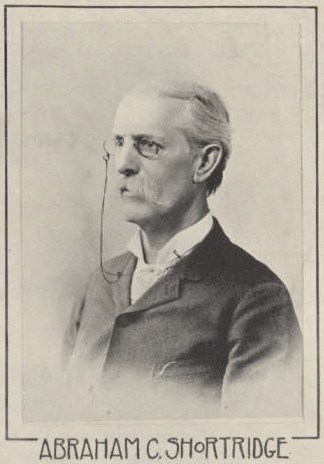

In May of 1869, the Indiana State Legislature passed a law ordering that all property should be taxed for the benefit of public school systems, without regard to the property owner’s race, and that all children, black or white, should be able to matriculate at their local public school. Still, section three of the act states “The Trustee or Trustees of each township, town or city, shall organize the colored children into separate schools, having all the rights and privileges of other schools of the township.” While this act was a huge positive step for black children, who beforehand were not guaranteed a free, public education, the law called for school segregation. In general, segregation came more naturally to elementary and middle schools, which were more numerous and served the children living closest to them. At this time, however, there was only one high school for all of the young men and women of Indianapolis. According the 1869 law, if there were not enough black students to justify separate schools, it was up to the trustees to find another means of education for these children. In 1872, although the superintendent and not a board trustee, Abraham C. Shortridge did just that.

After retiring from his position as IPS superintendent, Shortridge became the president of Purdue University, a position he held for just the 1874-1875 term. This picture appeared in the 1895 “Debris,” Purdue’s yearbook.

In a 1908 article penned by Shortridge for the Indianapolis News, the former superintendent explained how Indianapolis High School, today known as Shortridge High School, gained its first black student. In the early 1870s, there were only about six black teens looking to attend high school, so a segregated high school defied practicality. A group of local men prominent in the black community came together with a plan to file suit against Indianapolis Public Schools (IPS) and force them to admit black pupils to Indianapolis High School. Shortridge had a simpler idea. He asked the men to send their brightest, high-school age child to him on the first day of the new school year. On that day, Mary Alice Rann appeared before Shortridge and asked to enroll in the high school. He took her to the principal, George P. Brown, and plainly said, “Mr. Brown, here is a girl that wishes to enter the high school,” and then went back about his day. Shortridge would wait and see if anyone protested.

Miraculously, no one did; however, that does not mean that people weren’t against the admittance of Rann. In his article, Shortridge goes on to tell the story of one such dissenter. Editor of the now-defunct Indianapolis Daily Sentinel, and member of the IPS school board, J. J. Bingham, came to the high school to confront Shortridge about admitting a black pupil. After making a derogatory remark, Bingham said, “I have a long communication in my pocket now in regard to it.” He was threatening to publish his feelings in his new paper, which would surely stir up additional protesters. Shortridge replied, “That is a good place for it; better let it stay in your pocket.” In the end, Bingham published nothing. After four years of study, Mary Alice Rann graduated from Indianapolis High School.

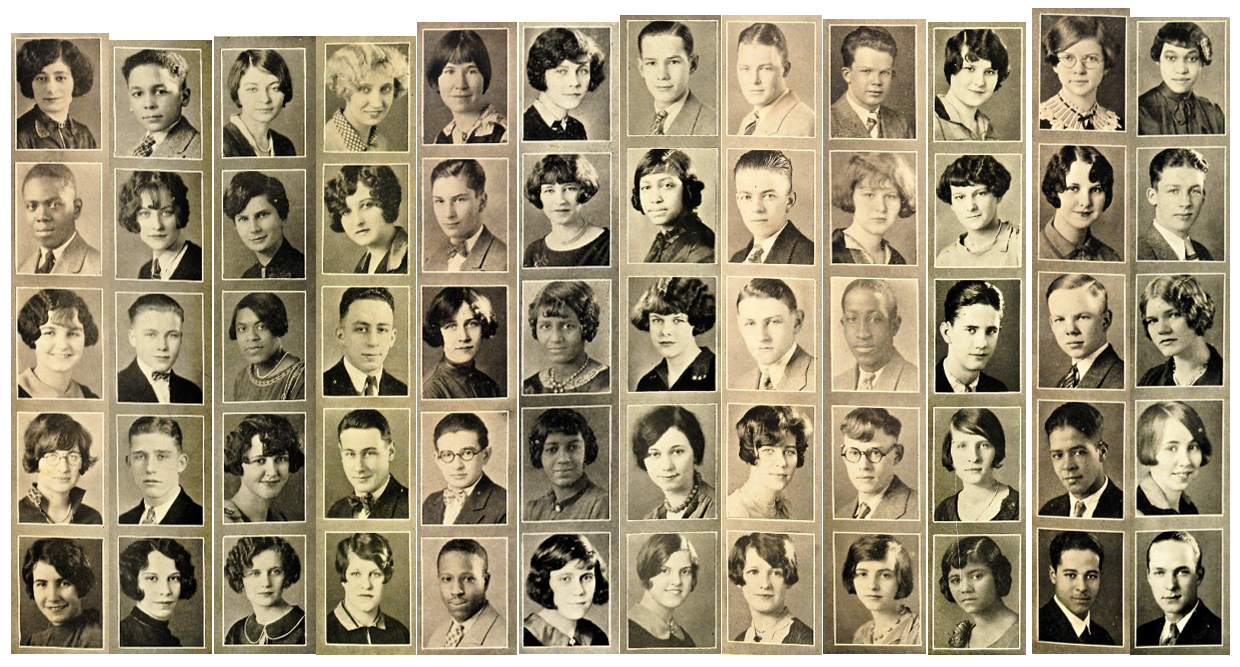

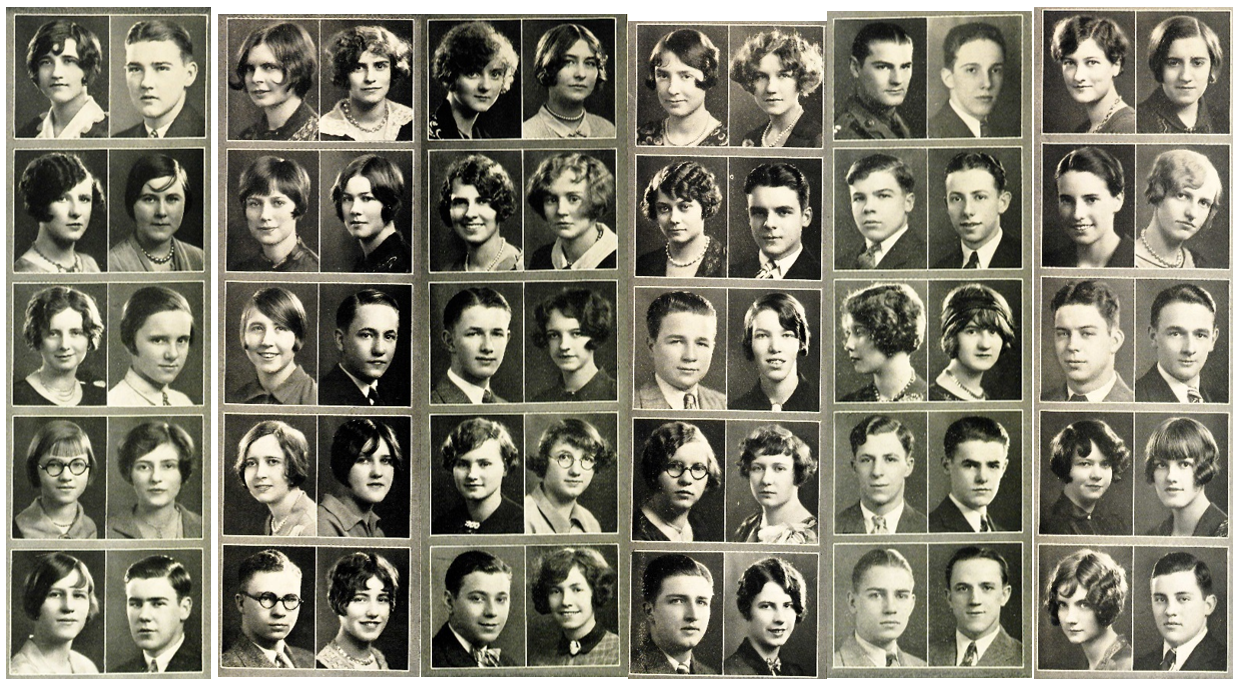

The part I find the most fascinating about history is how we can see facts within material culture and through archival documents. I found proof of the beginning of segregation in Indianapolis high schools on a whim. I wondered, would I be able to see segregation by looking at Shortridge High School yearbooks? Look at the images below. Notice a change? The first clump of senior photos are from the 1926-1927 term yearbook at Shortridge High School. Below that are several pages worth of senior pictures from the following term, 1927-1928. In this yearbook, you will find nothing but white faces, save one young man from the Philippines.

People often associate the decision to build Crispus Attucks High School with the Ku Klux Klan. This association is based on the fact that multiple IPS board members elected in 1925, along with Indianapolis city councilors, Governor Edward Jackson and Indianapolis Mayor John Duvall, were members of the KKK; however, it was actually the school board elected in 1921 who began the preparations for building Crispus Attucks. Sentiment for white supremacy was running rampant in the state well before 1925.

Many, if not most, in the black community in Indianapolis were against the creation of Crispus Attucks. They argued that this new school could not possibly provide the same opportunities, academically or vocationally, that the city’s three other high schools offered. Shortridge High School was considered one of the best in the nation, after all, and the majority of Indianapolis’ black high school students were enrolled there. Even with local protest and pending court cases, construction on the new school commenced. In the end, the school became one of the crown jewels of the neighborhood surrounding the Indiana Avenue corridor. It provided jobs for black teachers who were otherwise barred from teaching at white or even integrated schools. Because of the high level of competition for black teaching jobs, the teachers at Crispus Attucks were the best of the best. Many had advanced degrees and were better qualified to do their job than white teachers, and Crispus Attucks became a first rate school despite the circumstances that caused its founding.

Crispus Attucks High School, 1928. This photograph is part of the Bass Photo Co. Collection at the Indiana Historical Society.

In 1949, Indiana outlawed segregation in its schools; however, segregation continued in Indianapolis. Crispus Attucks began admitting white students in 1967, but the pupils remained more than predominantly black. In 1968, the federal government filed a complaint and took the IPS school board to court for continuing de jure (by law) segregation, while the school board argued that they were innocent and that IPS schools only suffered from de facto (by fact, or chance) segregation. In reality, there had been gerrymandering of school boundaries, which perpetuated segregation. After multiple appeals by the IPS school board, the federal court ordered that the city and IPS needed to facilitate a busing program to help reverse the years of segregation. The program bused black students living closer to the city center to township schools in more affluent, predominantly white neighborhoods. It began on a small scale in 1973 and then transitioned to a large-scale program over several years; many of the affected township schools did not begin participating in the program until 1981. White students living in the townships were never bused to predominantly black schools in the inner city. The federal court order mandating this program expired in 2016.

This blog post was written by Caitlyn Stypa, Indiana Young Readers Center assistant, Indiana State Library.