For over 100 years, the Indiana State Library has sought a solution to the “unserved” areas of Indiana. As someone who grew up in one of these areas, this has been a topic that I have long wanted to see addressed. As I look back at some of the articles written in the 1930s in Library Occurrent, I find that this issue has been on the minds of folks working with libraries for a long time. Maybe it’s time we started to change the conversation. What if we stopped talking about “unserved areas” and started talking about the “library deserts” that exist in our state?

In calling the areas unserved, we have unintentionally painted this as a problem for the libraries to deal with, and one that seems to be the fault of the libraries. “Why won’t the library serve those people?” First of all, having grown up in rural Hancock County before Sen. Beverly Gard was able to make changes with CEDIT, and change the service area, this was something the folks at the Hancock County Public Library wanted to see changed. While my friends and I would make the 20-30 minute drive to the Hancock County Public Library to do research, we were constantly teased by the worlds that could be opened up to us through all the books available for check out, but not to us. As high school students, all striving for admission and financial assistance to colleges, our focus was beyond the “why” we couldn’t check out the books, beyond the “why” behind the fact that we had to purchase most of the books we wanted to read. We had more immediate concerns that would impact our futures greatly, and didn’t even realize how much we were missing just because our neighbors had fought against paying taxes to the library.

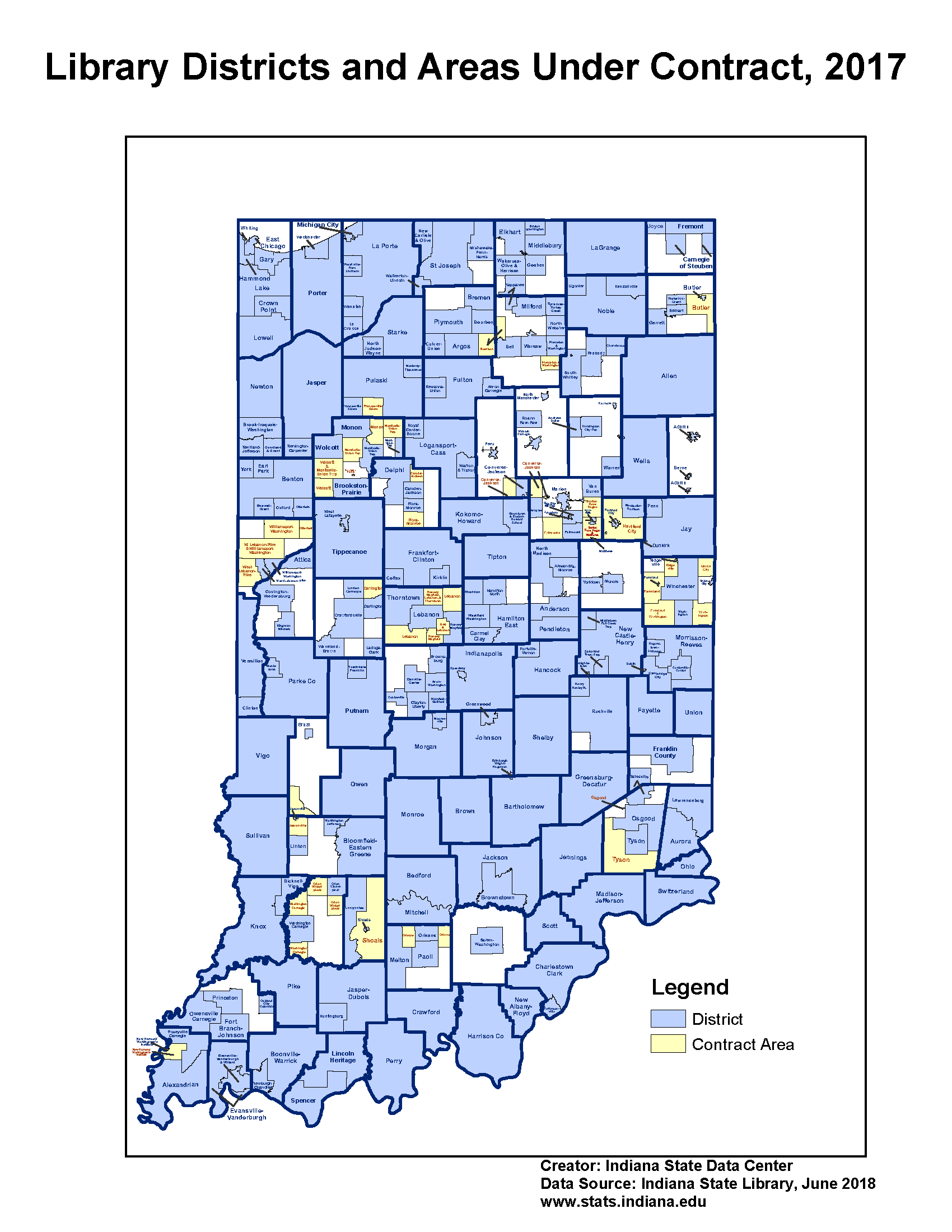

By talking about library deserts, we can begin to shape the conversation around the citizens of this state who are at a disadvantage. Yes, they are welcome to go to any public library and use the materials while there, but it’s not the same level of access that the residents of that district have. It is a civic inequity that exists because of decisions made long ago and/or by a vocal group of individuals striving to protect their own interests. Every child in this state can expect to receive an education, starting at least with kindergarten. But there is so much work to do before those children ever get to kindergarten. Every Child Ready to Read and other early literacy programs have been growing in popularity throughout the public library network. But what about those pre-K kids who don’t have a public library of their own? Maybe they’ll still get to story hours, but what fun will it be when all of their friends get to leave with stacks with books and they have to go home empty-handed? And our colleagues in library districts that are juxtaposed with these library deserts have to have difficult conversations every day explaining what we all know: that library service is not free, that patrons contribute to the fiscal success of every library through some kind of tax and that the individuals who are paying those taxes should not have to carry the burden for everyone who doesn’t pay taxes.

Inequities among students who have restricted access to adequate broadband, varying levels of digital and general literacy and inequity in income noticeably affects their potential, as highlighted by this February 2019 ACT report. Obviously, library access does not solve all these problems, but ensuring all citizens have a basic level of access to information may help level the playing field for all our citizens. The ability to convey the benefits of library access to all members of our communities, and to all citizens of the state could be enhanced if we made a minor shift in our language to better reach more people.

This post was written by Wendy Knapp, deputy director of Statewide Services at the Indiana State Library.