The following details the general day-to-day workings in the basement level of the Indiana State Library where the Indiana Talking Book and Braille Library conducts its circulation operations. Those who work in this department help many people who are unable to use standard printed reading material – and may not be able to use the library – gain access to library materials. This allows hundreds of people to take part in the Talking Book and Braille Library every day.

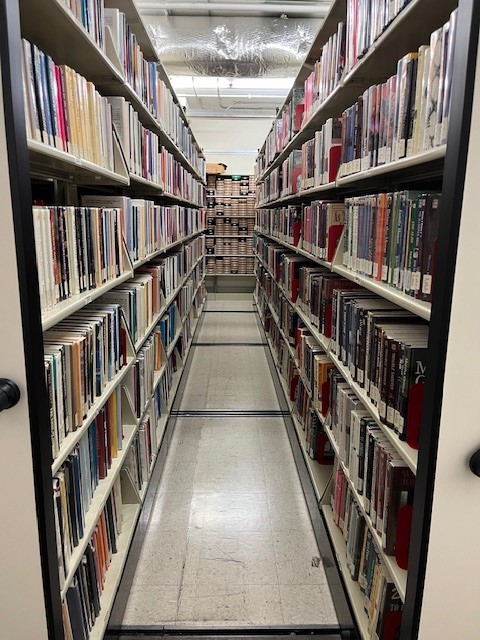

The process begins in the basement of the Indiana State Library, where hundreds of books are circulated to and from patrons. The basement is like nearly any other part of the library’s stacks, with the small exception being that all items are a part of the Talking Book and Braille Library and each item being circulated is a different form of an accessible book. From large print books to audio books to braille, every day there is an ebb and flow of accessible reading material sent out and returned, and here is how it works:

The day starts with requested large print books being pulled from the shelves in the stacks of the basement. They are then checked out to be sent through the InfoExpress courier service to the requesting libraries to be held for their patrons. From there, these books are transferred to the State Library’s circulation desk where they are processed by circulation staff and sent on their way via the courier service. Any incoming books are brought down and checked back in as well.

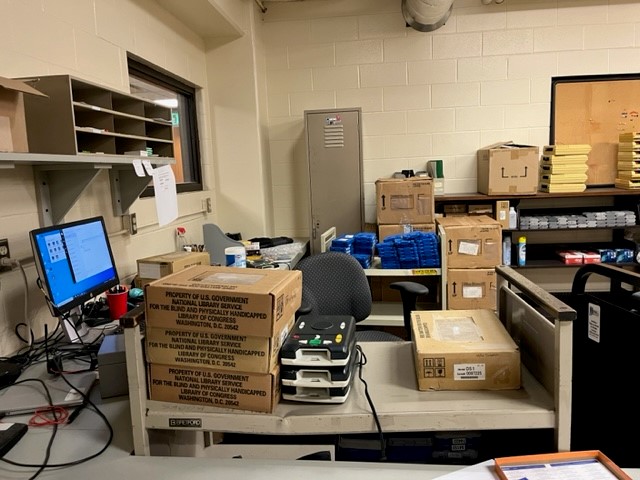

TBBL staff opening the returned mail to check in the talking books cartridges.

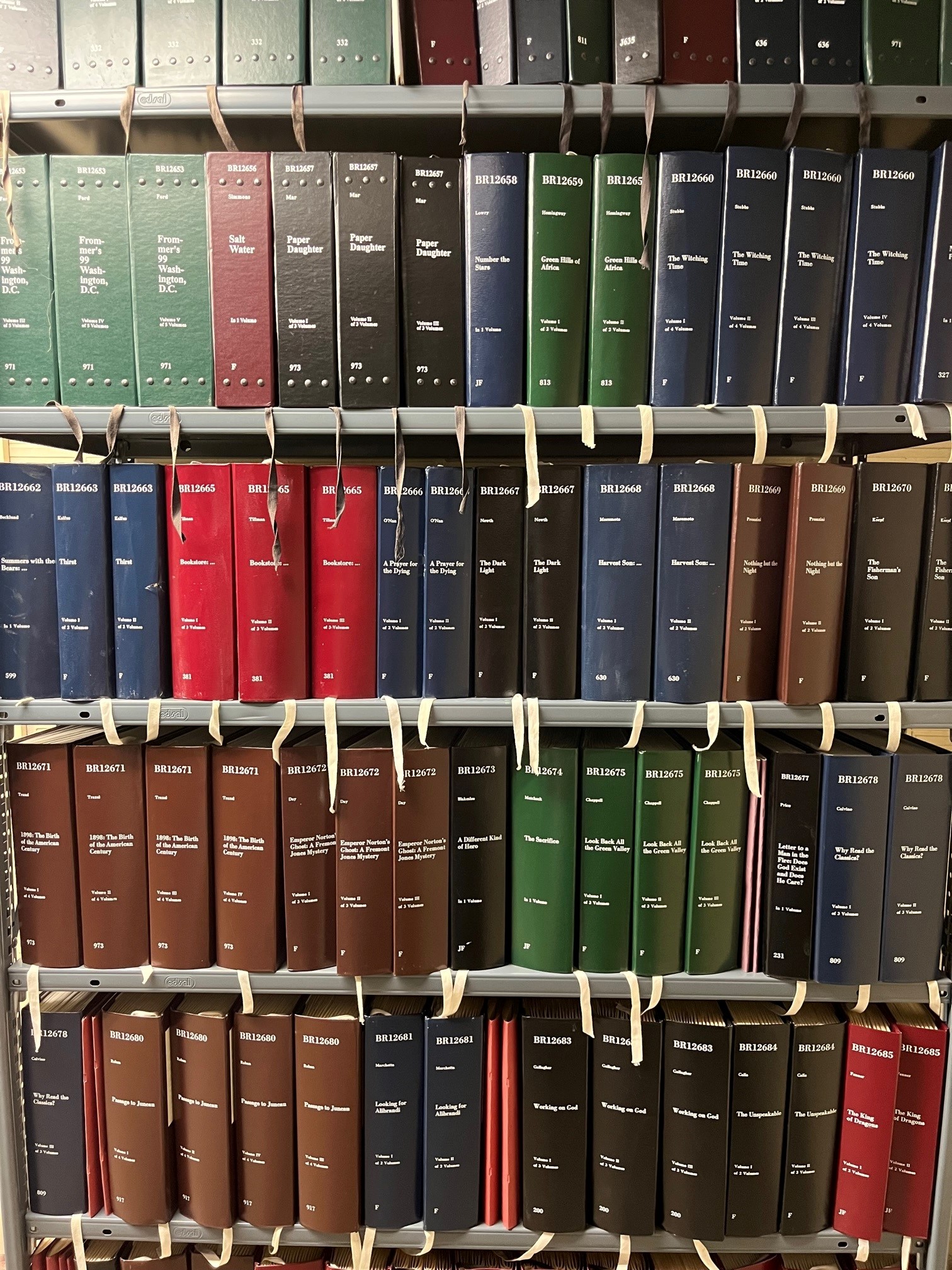

Next, large print and braille books are mailed directly to patrons through the Talking Books and Braille Library. These books are pulled from shelves in the same manner as the other books, as well as checked out, but rather than being sent to circulation, these books are bagged up along with their associated mailing cards and set in mail tubs to be sent out later in the day through the United States Post Office. The cases used for the braille books are tough, black, Velcro-enclosed boxes that help in the safety of the books during transportation. All these books are mailed as “free matter for the blind,” and no postage is paid by the library or the patrons.

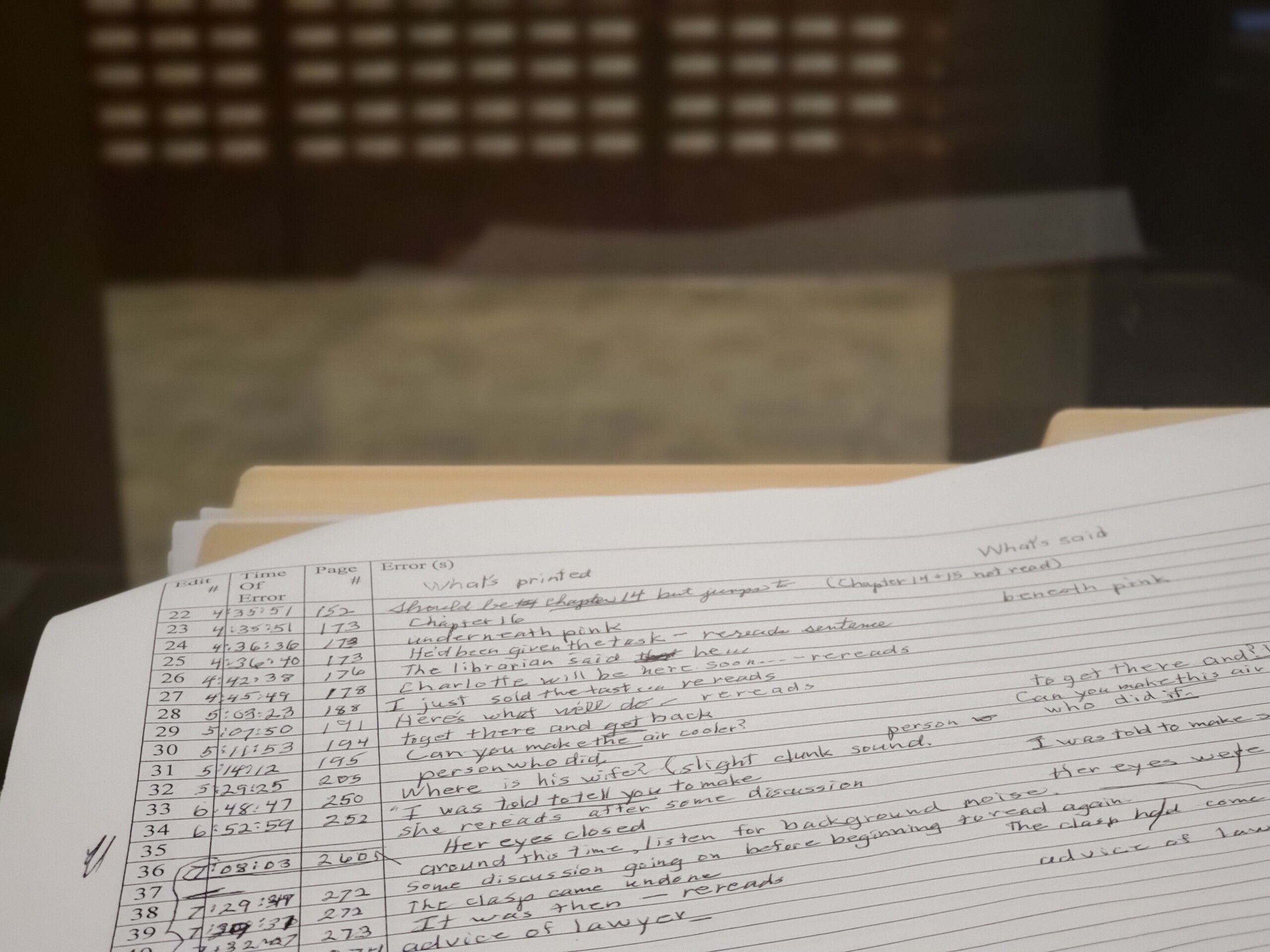

After all the outgoing physical books have been finished, next comes the audio book duplication. Audio books are distributed through the Talking Book and Braille Library via Duplication on Demand. USB drives that are larger than traditional drives, and are easier to manipulate, are then placed inside a small machine connected to a computer known as Gutenberg. While connected to Gutenberg, books that have been assigned to patrons are copied onto the USB drives and within a few minutes are ready to be sent out. The cartridges are pulled from the machine, causing their mailing cards to be printed along with the books contained on the device. The cartridges are placed inside their special blue mailing cases, along with their card for the destination, and sent along with the rest of the mail. Every day, anywhere from 100 to potentially upwards of 500 of these are sent out, with each USB containing anywhere from one to around 10 books.

A mail tub with outgoing talking book cartridges.

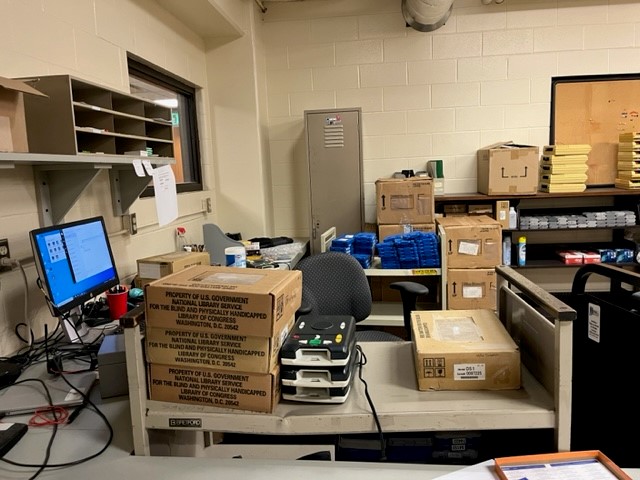

Alongside the Duplication on Demand cartridges, digital players must be sent out as well for patrons to be able to listen to these books. Players are held on to, often for years at a time, so the amount of players circulating each day is far lower than the amount of cartridges. They are kept waiting on shelves ready to be sent out as needed. Headphones are occasionally sent along with these players and are kept in the same area. Mailing cards are printed for all requested devices and they are checked out in KLAS, and sent out as well. This marks the end of the outgoing materials from the basement section of the Talking Book and Braille Library.

Talking book players are stored here until they are either sent to a patron or sent to the repair shop for evaluation and cleaning.

Next comes the incoming material. Every day, just as hundreds of books split between the three types go out, a similar amount comes in. Mail tubs arrive in the middle of the day at the loading dock. Mail is separated and sorted, and then the process of checking everything in starts. Books are checked back in, making them available to be borrowed again. Duplication on Demand cartridges are separated from their cases and scanned to become available to be overwritten with new books the following day. Players are marked to be refreshed or repaired and placed on holding shelves where they will be sent to the repair group in Fort Wayne. The repair group is a volunteer organization that works with talking book players from the Indiana State Library, as well as a few other states. Once at the repair group they will be checked for any issues, fixed of any that are found, and returned later to become available for circulation once again. Alongside these returned materials from patrons, repaired machines could arrive with this mail as well.

Hopefully, this look into the day-to-day operations of the Indiana Talking Book and Braille Library has been informative and insightful.

This post was submitted by Derrick Fraser, Indiana Talking Book and Braille Library.

However, due to age, rough handling and heavy usage – as well as leaks and temperature control issues – a portion of the braille books were no longer usable or fit for circulation. Additionally, many of the older nonfiction books contained outdated information on medicine, health, technology, job training and legal information. With the objective of maintaining the quality of the collection, each member of the Indiana Talking Book and Braille Library staff was assigned a handful of sections from the braille collection and charged with weeding out these damaged and outdated items, and cleaning and shifting the remaining books.

However, due to age, rough handling and heavy usage – as well as leaks and temperature control issues – a portion of the braille books were no longer usable or fit for circulation. Additionally, many of the older nonfiction books contained outdated information on medicine, health, technology, job training and legal information. With the objective of maintaining the quality of the collection, each member of the Indiana Talking Book and Braille Library staff was assigned a handful of sections from the braille collection and charged with weeding out these damaged and outdated items, and cleaning and shifting the remaining books. The amount of weeding was significant in the beginning, since the project started with the oldest books, which had been circulating longest, therefore receiving the heaviest damage. After the first few rounds of weeding, cleaning and shifting became the priority. Like all Talking Book and Braille Library collections, the braille collection is sent by mail to patrons statewide. Without regular cleaning, dirt and grime easily accumulated on book covers, inside pages and subsequently on the shelves. Similarly to the weeding, the need for cleaning was heavier in the earlier stages of the project.

The amount of weeding was significant in the beginning, since the project started with the oldest books, which had been circulating longest, therefore receiving the heaviest damage. After the first few rounds of weeding, cleaning and shifting became the priority. Like all Talking Book and Braille Library collections, the braille collection is sent by mail to patrons statewide. Without regular cleaning, dirt and grime easily accumulated on book covers, inside pages and subsequently on the shelves. Similarly to the weeding, the need for cleaning was heavier in the earlier stages of the project. The Talking Book and Braille Library staff is currently in the final stages of the 18-month braille book project. With weeding and much of the cleaning finished, the main focus has become shifting the collection. Since new braille books continue to arrive on a weekly basis, staff is eager to finish the last of the shifting and open a portion of the storage room for the incoming braille books. The braille book project will officially be completed in December.

The Talking Book and Braille Library staff is currently in the final stages of the 18-month braille book project. With weeding and much of the cleaning finished, the main focus has become shifting the collection. Since new braille books continue to arrive on a weekly basis, staff is eager to finish the last of the shifting and open a portion of the storage room for the incoming braille books. The braille book project will officially be completed in December.