As a manuscripts librarian, sometimes I come across items in our collections which point to bizarre and bemusing events in our nation’s history. What’s the old adage? Fact is stranger than fiction. Recently, I discovered a document relating to one of those historical oddities: The so-called Great Camel Experiment of the 1850s.

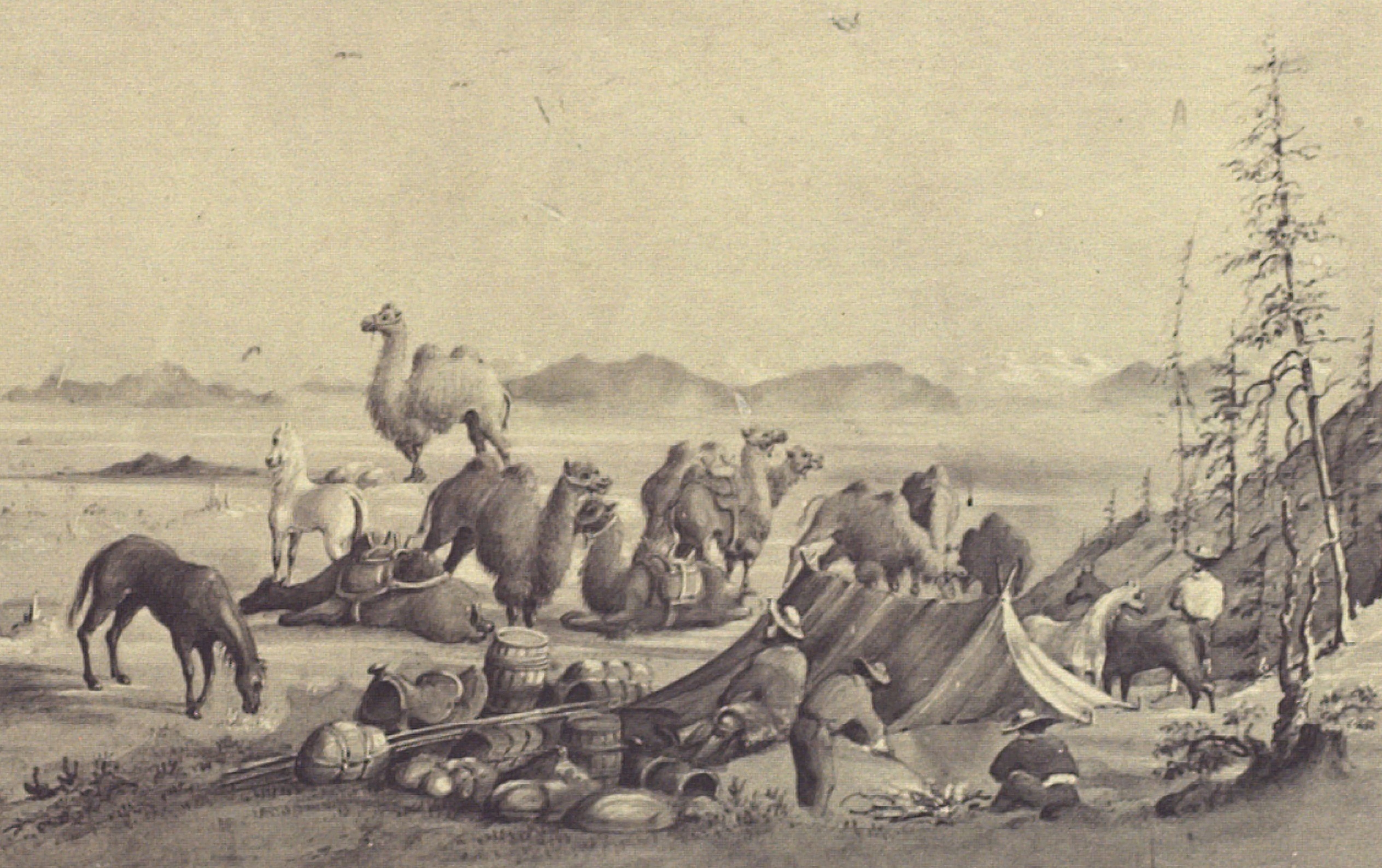

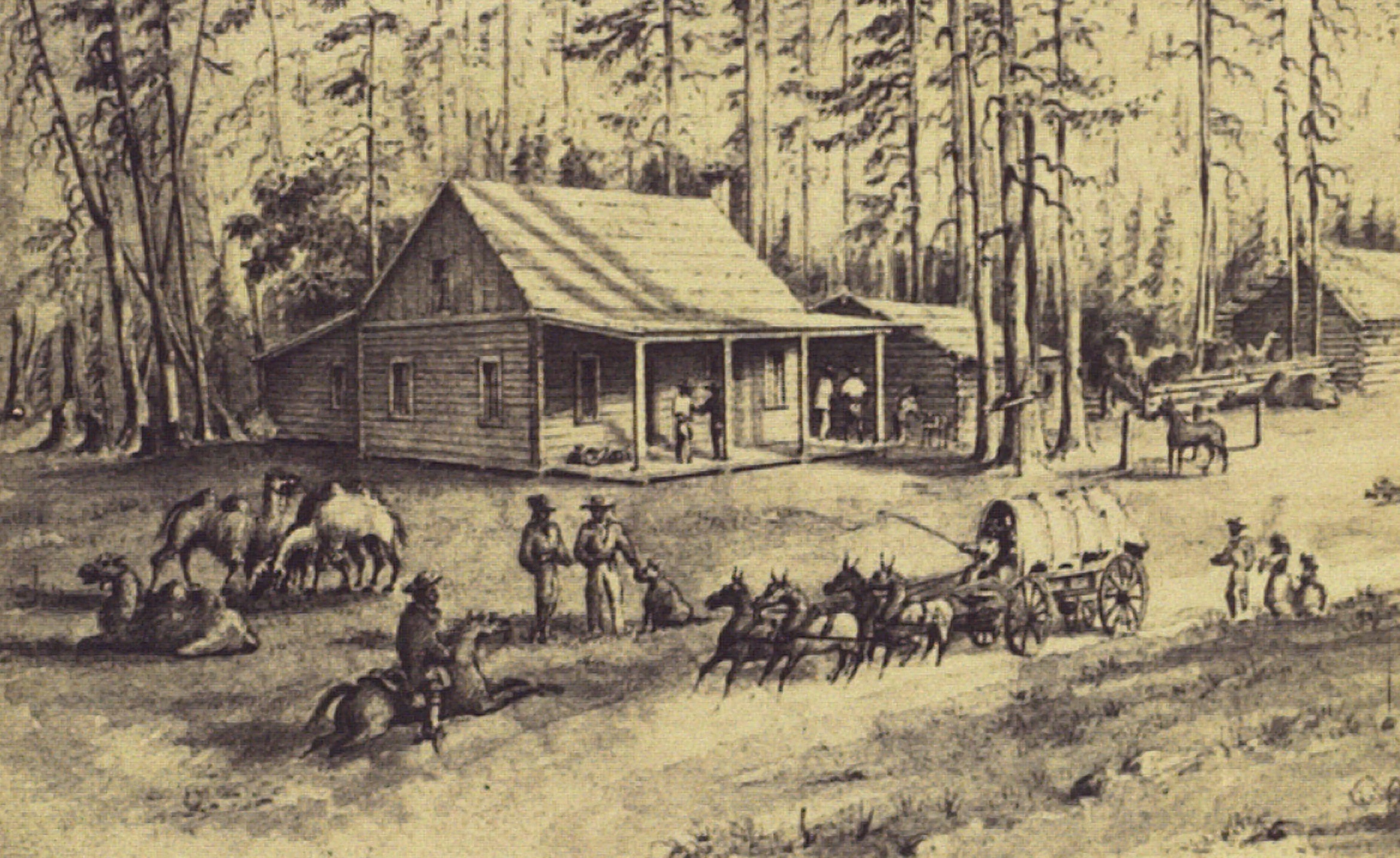

Drawing of Bactrian camels in Carson Valley, circa 1870. Source: Edward Vischer, “Vischer’s Pictorial of California,” 1870. View no. 47. http://ccdl.libraries.claremont.edu/cdm/ref/collection/vdp/id/1332

The Document

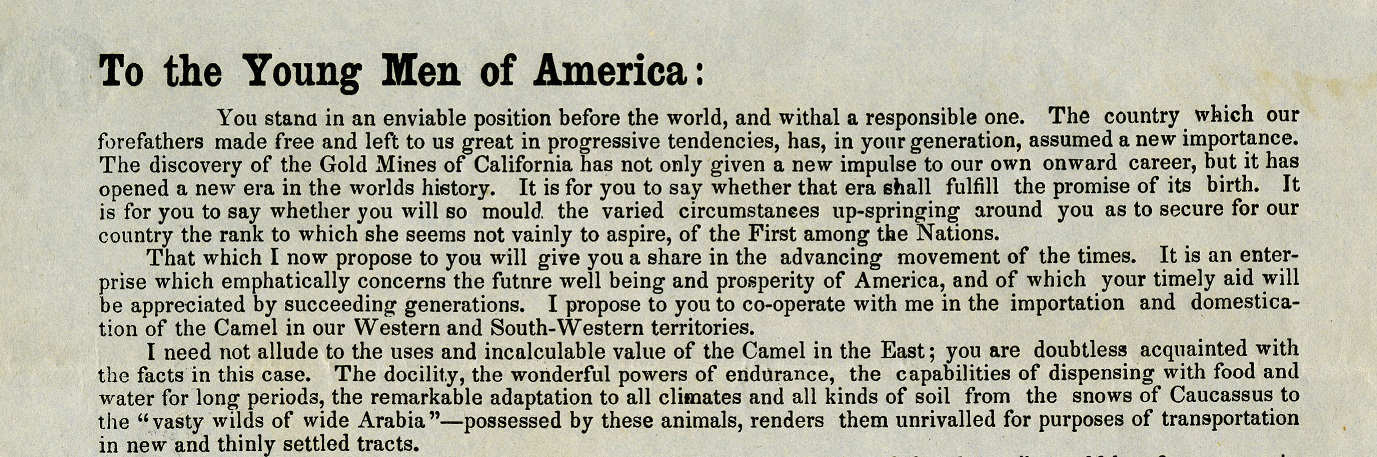

On Feb. 5, 1850 in Boston Charles Wilkins Webber—journalist, author and adventurer—drafted a circular “to the Young Men of America.” He hoped to entice young go-getters to invest in his new venture: the importation of 50 “long-legged, sure-footed, steady, but swift moving ‘ships of the desert.’”

Excerpt of C.W. Webber’s circular soliciting investors in his camel import enterprise, 1850. Source: Ewing family collection (L323), Indiana State Library, http://digitalcollections.library.in.gov.

In the missive, Webber provided several examples for the potential utility of camels in the United States, ranging from the impractical (camel expresses for delivery in the upper Midwest) to the disturbing (the extermination of Native Americans in the Great Plains). However, the most convincing proposal and primary aim of his endeavor was to use camels to establish a “shorter, safer and a cheaper route” overland to California.

Gold Feverish and Footsore

Two years after the discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill in 1848, the California Gold Rush was in full swing. Thousands charged to California in the hopes of plucking easy fortunes from the territory’s auriferous rivers. The first transcontinental railroad wouldn’t be completed for 16 years and the two transportation options—by ship and by hoof—were almost equally problematic, arduous and treacherous.

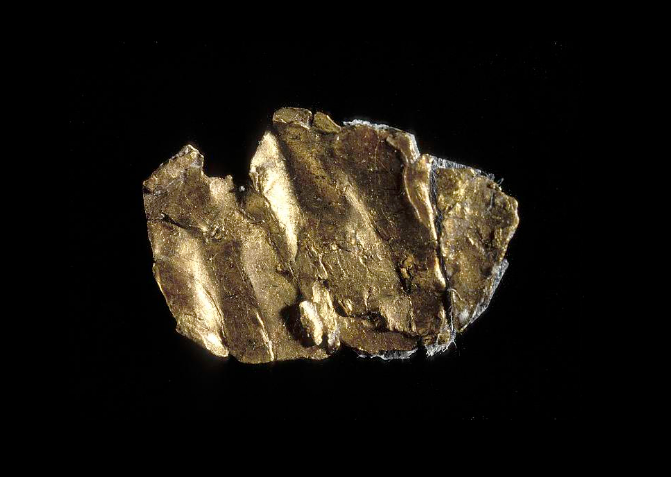

Presumably the first piece of gold discover at Sutter’s Mill in California, 1848. Source: National Museum of American History, Kenneth E. Behring Center, http://collections.si.edu.

The southwestern route, the Gila Trail (also known as the Southern Emigrant Trail), traversed great stretches of desert which killed pack animals by the score. There were also other hazards—accidents, exhaustion and diseases among the most prominent. Webber himself, intent on leading an expedition to the Colorado and Gila rivers in Arizona Territory, lost his party’s horses to Comanche raiders at Corpus Christi, Texas less than a year before proposing his camel enterprise.

Broadside for potential emigrants during the California Gold Rush, 1849. Source: Boston Rare Maps, http://bostonraremaps.com.

By 1855, approximately 300,000 people had migrated to California lured by the promise of gold, nearly half of whom had traveled overland from east to west. And all those people needed supplies—food stuffs, clothing, prospecting and mining gear and other goods—which had to travel the same routes as the ‘49ers. Is it any wonder businessmen and pioneers saw an opportunity for new means of transportation?

Why Camels?

Webber was not the first American to propose the use of camels in the U.S. As far back as 1836, the army had flirted with idea of the dromedary’s application for military transport, but it was only in 1848 that they began giving it serious consideration.

Camels’ adaptions for thermoregulation and high water retention made them well-suited to high temperatures and arid conditions. Moreover, the ungulates could bear loads several times those of pack mules. These capabilities made them appear ideal for crossing the deserts of the Southwest and the idea was surprisingly popular with many Americans.

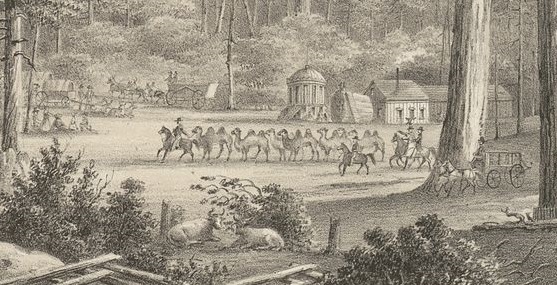

Riders herding camels on the grounds of the Mammoth Grove Hotel, circa 1870. Source: Edward Vischer, “Vischer’s Pictorial of California,” 1870. View no. 18. http://ccdl.libraries.claremont.edu/cdm/ref/collection/vdp/id/1332

An article in the Wabash Courier of Terre Haute, Indiana on July 26, 1856 described the camels as “uncouth and awkward to the extreme,” bearing “a resemblance to the stupid turkey.” Despite their opinion of the camel’s homeliness, the authors finally concluded the enterprise would prove successful, with camel caravans “thread[ing] the weary wastes of the West, and the rugged defiles of the mountains connecting our Eastern and Western fields of enterprise and empire.”

Under Secretary of War Jefferson Davis (yes, that Jefferson Davis), 33 dromedaries (one-humped camels) and Bactrian camels (two-humped) were imported for the army’s use. In 1857, Edward F. Beale led the U.S. Camel Corps (no joke) from San Antonio to Fort Defiance, Arizona and then on to California to test the animals’ potential for military supply transport. At the terminus, Beale reported the experiment as a triumph and avowed he would prefer one camel to four mules for transportation in desert conditions.

Why It Failed

A handful of other army expeditions employed camels in the 1850s, but the U.S. Civil War put an end to the camels’ use in military operations. It certainly didn’t help the camel’s case that one of its biggest proponents, Jefferson Davis, defected from the Union to become president of the Confederacy. After the war, camels were largely viewed as irrelevant as modes of transport while the focus shifted to completing the transcontinental railroad.

As for Webber’s enterprise, four years after he wrote his circular, it seemed his dream would be realized. The New York State Legislature passed an act to incorporate the American Camel Company on April 15, 1854 with Webber listed as one of its commissioners. However, the endeavor died in 1855 and was never resurrected. The California Gold Rush had peaked in 1852 and the company failed to get over the hump (ba-dum-bump).

Act to incorporate the American Camel Company, 1854. Source: New York State Legislature, Laws of the State of New York, http://babel.hathitrust.org.

Coda

Was the failure of the Great Camel Experiment really a “calamity?” No, not really (the alliterative assonance of “camel calamity” [camelamity?] was just too good to pass up).

Camels outside Holden’s Station in Hermit Valley in the Sierra Mountains, circa 1870. Source: Edward Vischer, “Vischer’s Pictorial of California,” 1870. View no. 19. http://ccdl.libraries.claremont.edu/cdm/ref/collection/vdp/id/1332

Overall, the use of camels for military transportation proved more efficient than pack mules and might have had more widespread appeal if the Civil War hadn’t completely diverted the military’s attention. But ultimately, it was the steam engine that obliterated any practicality of using camels as a means of transportation in the United States. As for the fate of those camels imported to the U.S., many were sold to entrepreneurs who used them to carry supplies to remote mining operations, while some went free and presumably roamed the Southwest until they died off. Residents of Arizona, Nevada, Colorado and Utah reported sighting camels in the desert as late as the early 1900s. (In contrast, for an example of a thriving, wild, non-indigenous camel populations, see this article on the feral camels in Australia).

What ever happened to the camel crusader, C.W. Webber?

After giving up his camel endeavor, Webber joined notorious filibuster William Walker in the invasion of Nicaragua and was killed in action at the fourth battle of Rivas on April 11, 1856.

Webber had lived in an interesting life, having dabbled in all sorts of careers from medicine to theology, but his ultimate success lay in writing. He was a successful journalist and wrote several books based on his experiences working with the Texas Rangers and traveling the West, which are in the public domain and freely available online. Webber’s flair for the dramatic really shines in his camel circular. You can view the full circular here in the Indiana State Library Digital Collections (http://digitalcollections.library.in.gov).

For more information on camels and their connection to Indiana, check out this blog post from Hoosier State Chronicles.

This blog post was written by Rare Books and Manuscripts Librarian Brittany Kropf. For more information, contact the Rare Books and Manuscripts Division at (317) 232-3671 or “Ask-A-Librarian” at http://www.in.gov/library/ask.htm.

I think the utility of camels in the United States was to establish a “shorter, safer and a cheaper route” overland to California…-:)

When businessmen and pioneers saw an opportunity for new means of transportation? -:)