Spring has arrived and many genealogists will be putting their research aside to spend more time outdoors, but did you know you don’t have to choose one over the other? Take your genealogy outside by growing plants with ties to your family heritage.

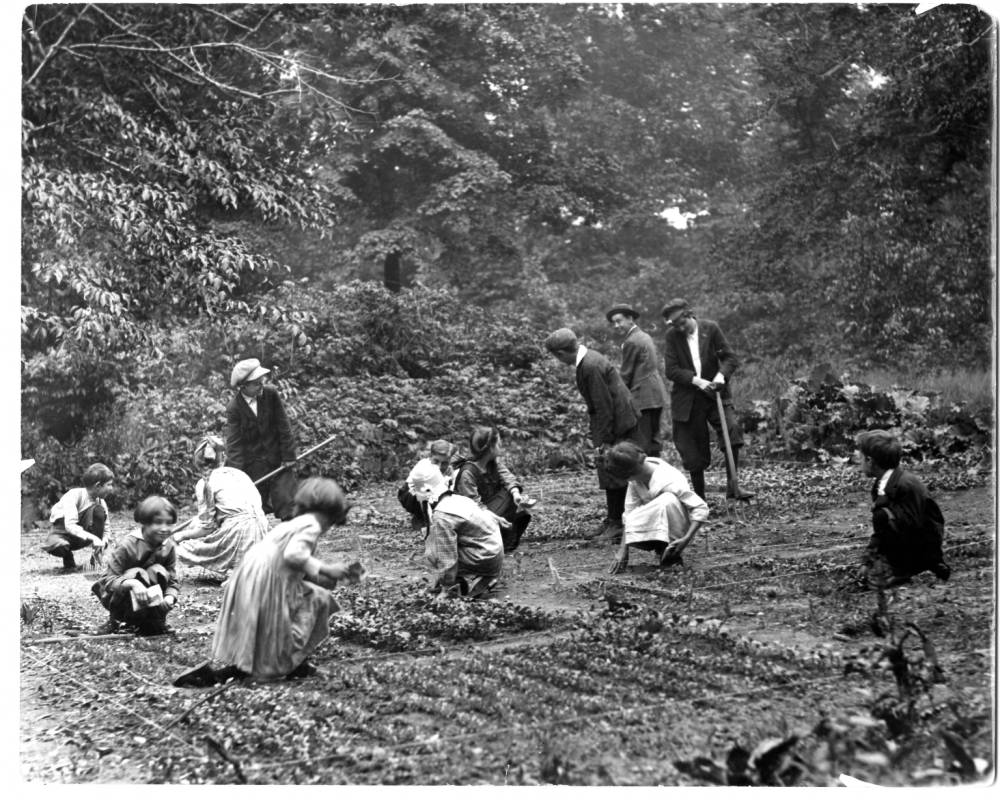

In addition to reaping the benefits of spending time in nature and beautifying your outdoor space, gardening with ancestors in mind brings family history to life. It may come naturally to those who don’t even realize starting the seeds an aunt passed down or planting grandma’s favorite tomato variety is a connection to their heritage. Others may be interested in learning more about the flowers, fruits and vegetables their ancestors raised so they can grow them as well.

The simplest way to get started is by taking inventory of your own memories and noting plants which are meaningful to you and your family. For example, my grandmother grew grapes and hot peppers in the backyard garden of her small ranch-style home in Speedway. In the limited space she had, she chose those specific plants for a reason. She probably learned to raise them from her own mother while she was a young girl. Planting them in my garden doesn’t just remind me of my grandmother’s loving kindness, it’s a connection to those ancestors that passed along their knowledge of growing those plants for generations.

Next, reach out to family members and ask about their gardens or what they remember growing in their childhood. In these conversations you may discover that your relatives still have access to some prized family favorites. They may be willing to gift you a clipping from a raspberry bush that’s been in the family for generations or share seeds from prize-winning pumpkins. Maybe you’ll learn there are treasured plants at the family homestead that you could transplant into your own space.

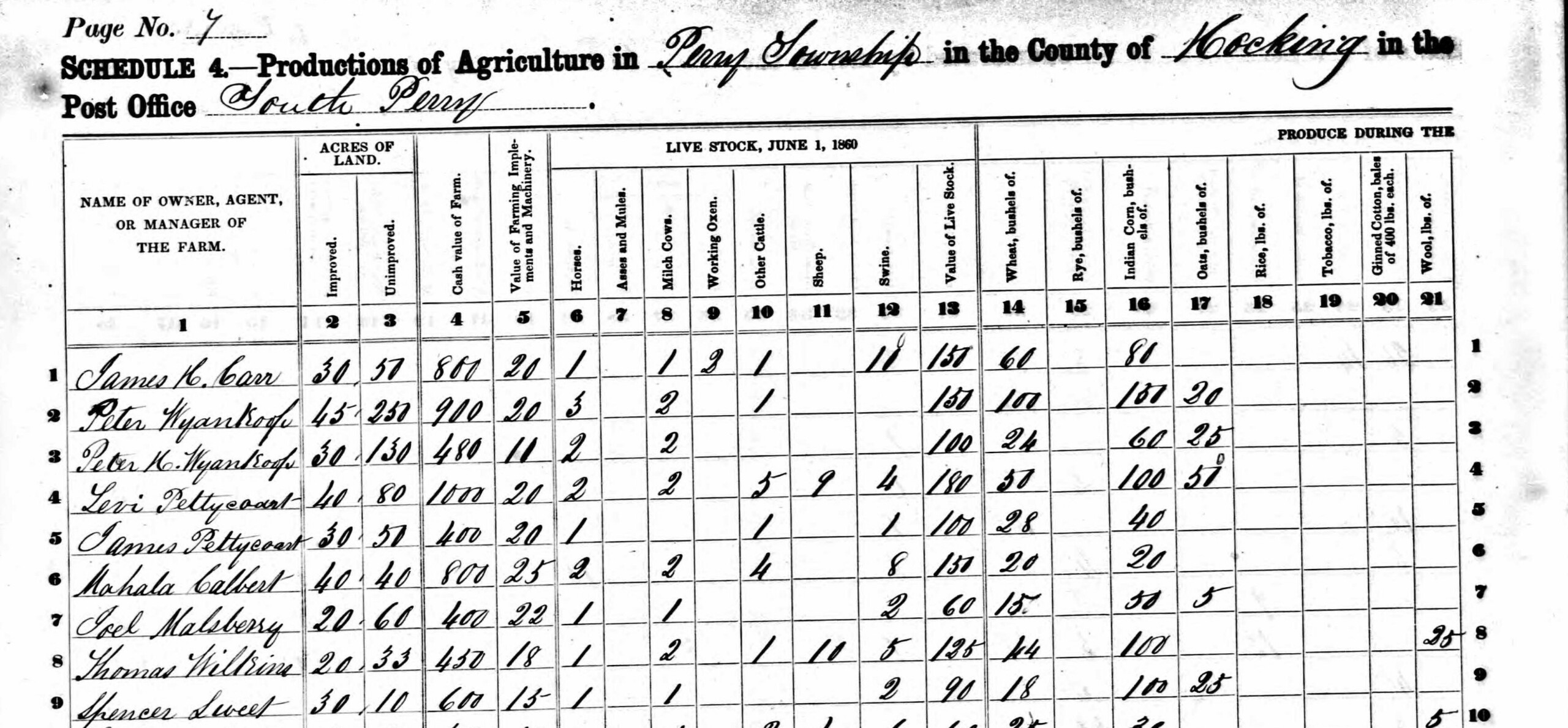

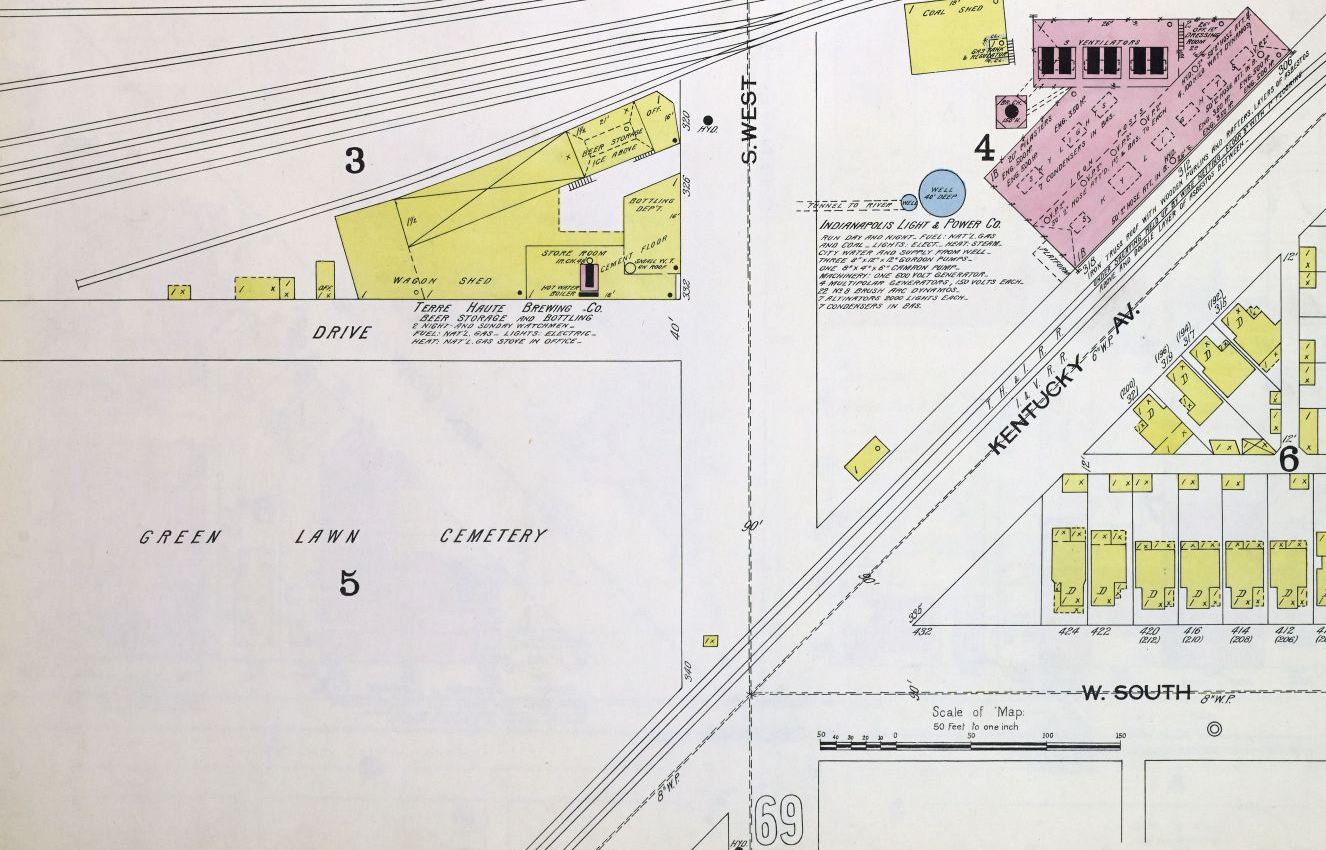

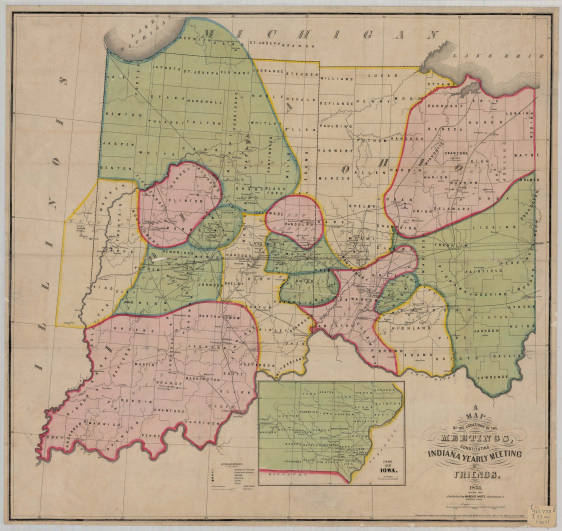

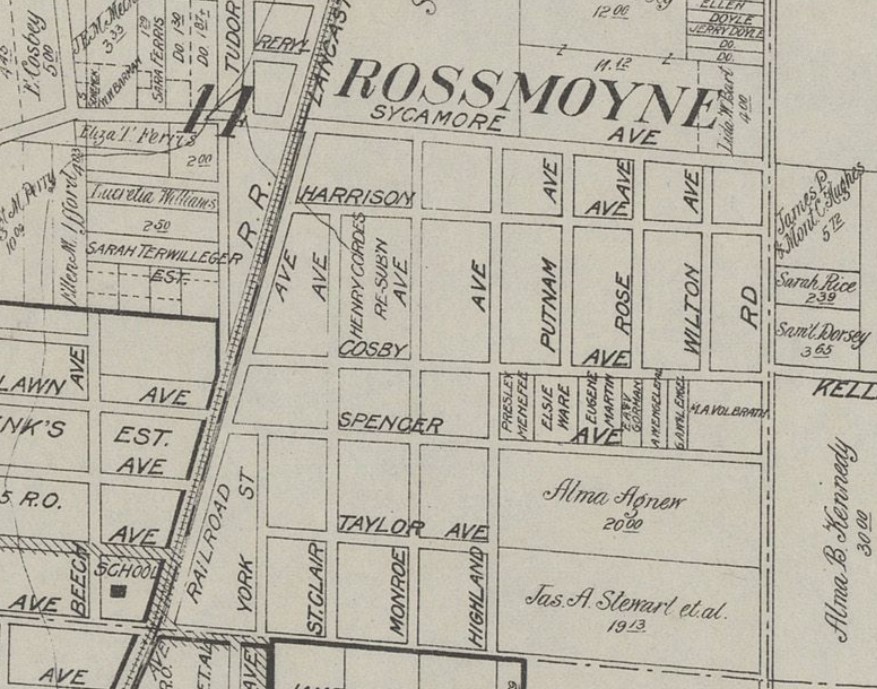

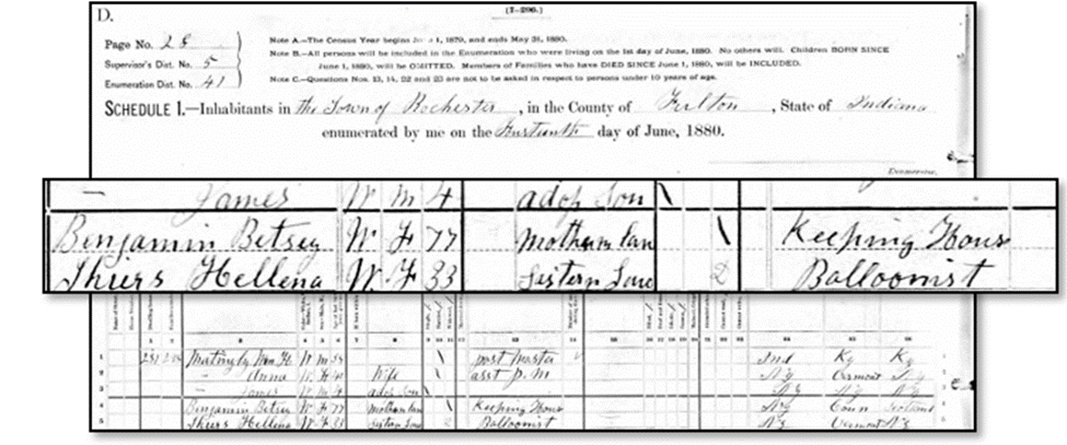

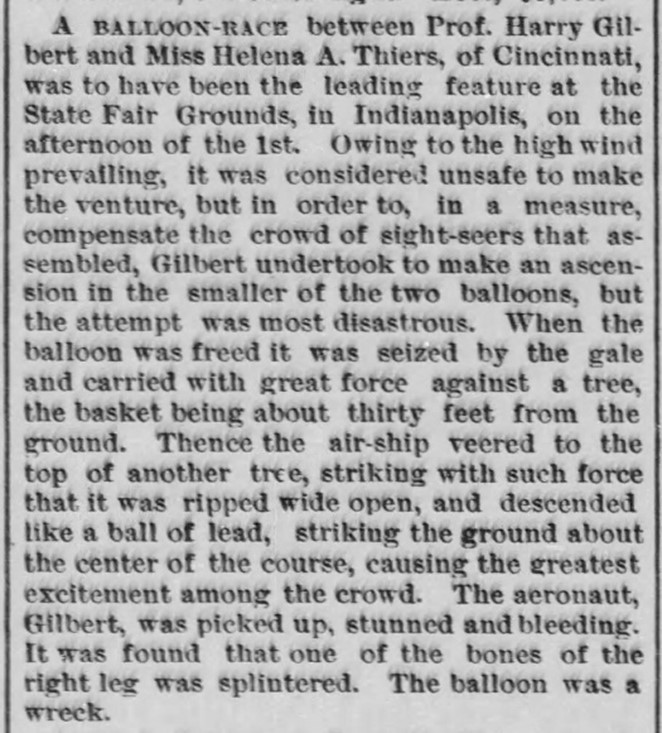

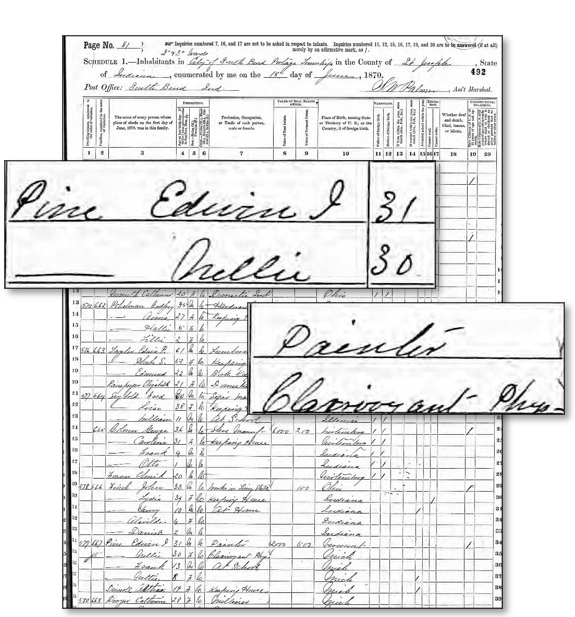

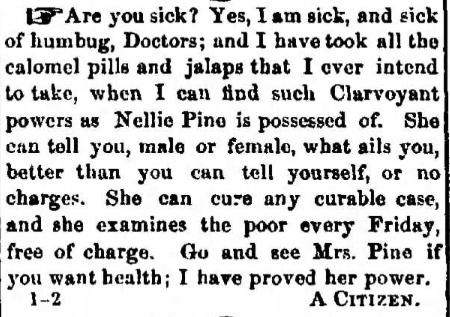

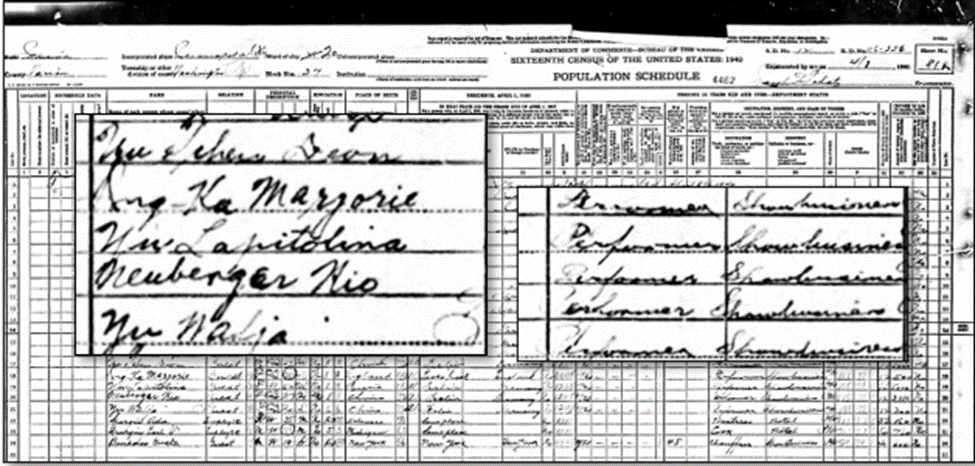

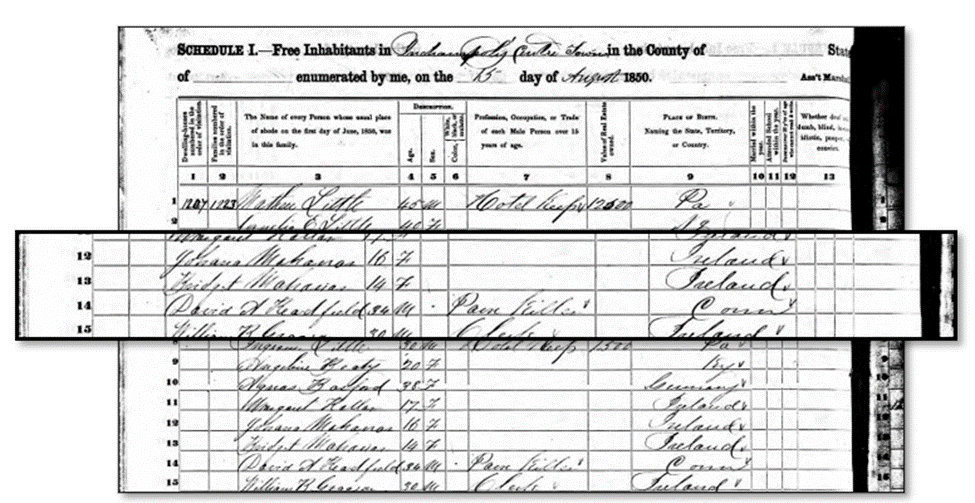

Before you abandon your genealogy research to start planting, use it to learn about the crops ancestors once grew. There are many helpful resources to search for information. For example, the U.S. agricultural censuses inventory the livestock and produce raised by farmers. If your ancestors are from Indiana, the 1850, 1860, 1870 and 1880 Indiana agricultural censuses are available at The Indiana State Library on microfilm. Ancestry Library Edition can be searched for free on the library’s computers and includes agricultural censuses from various other U.S. states. For example, I learned from this 1860 Pickaway County, Ohio agricultural census my ancestor grew corn, oats, potatoes and wheat on their farm.

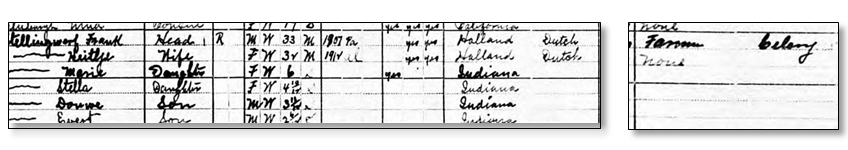

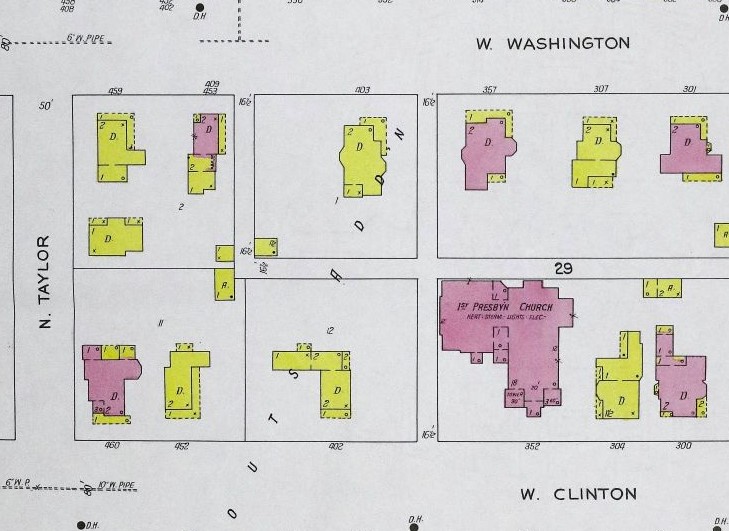

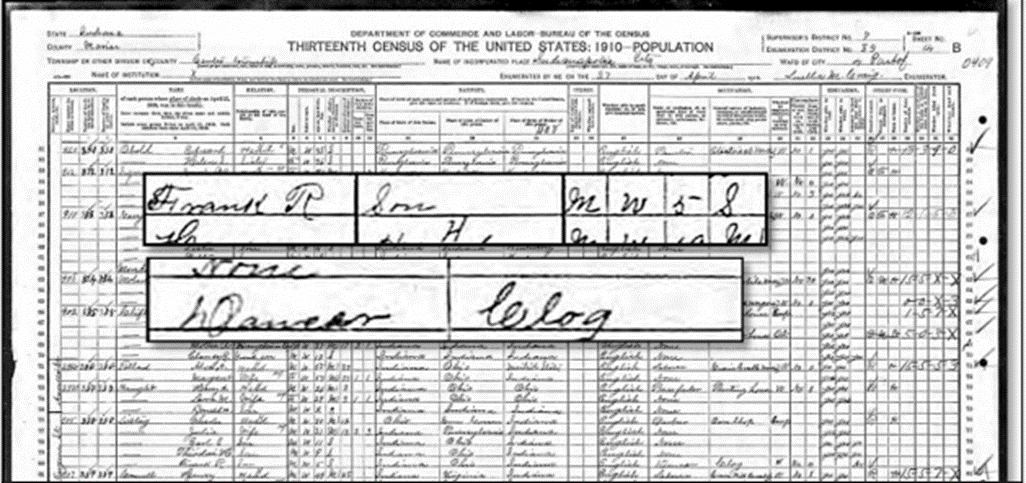

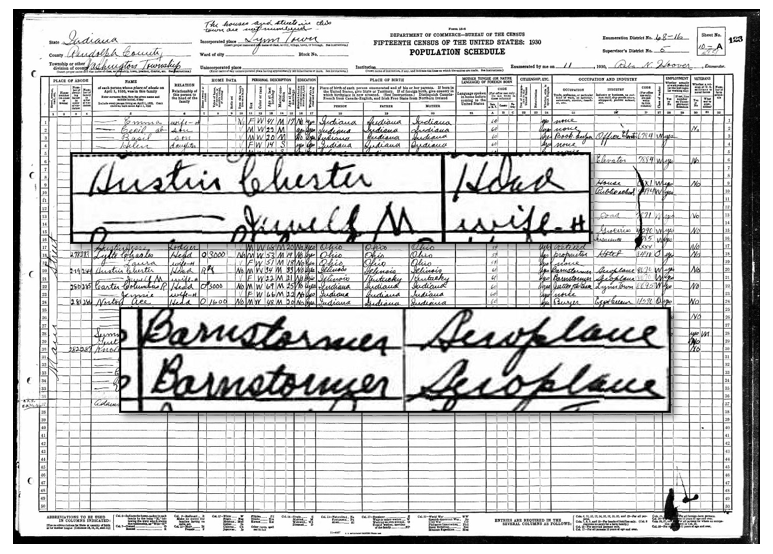

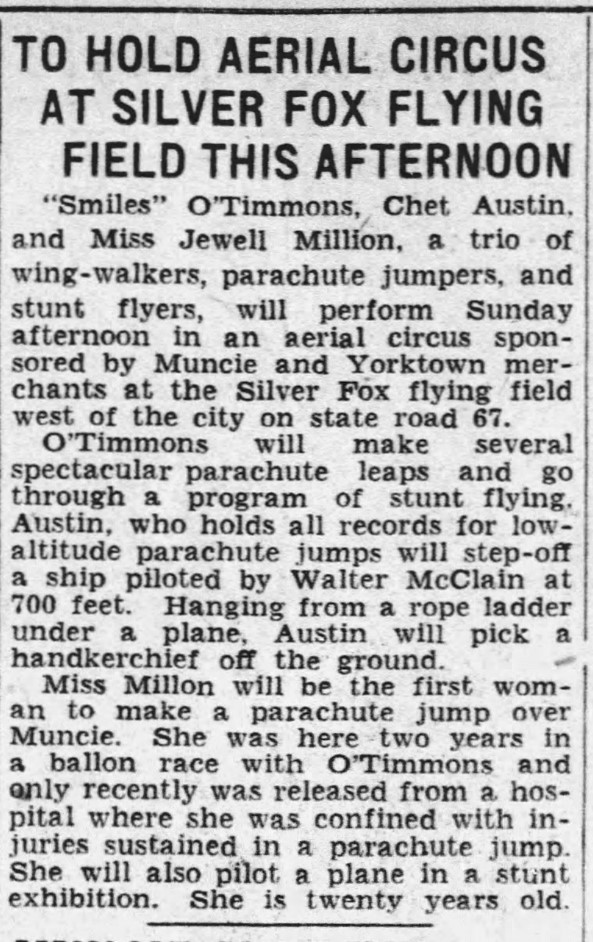

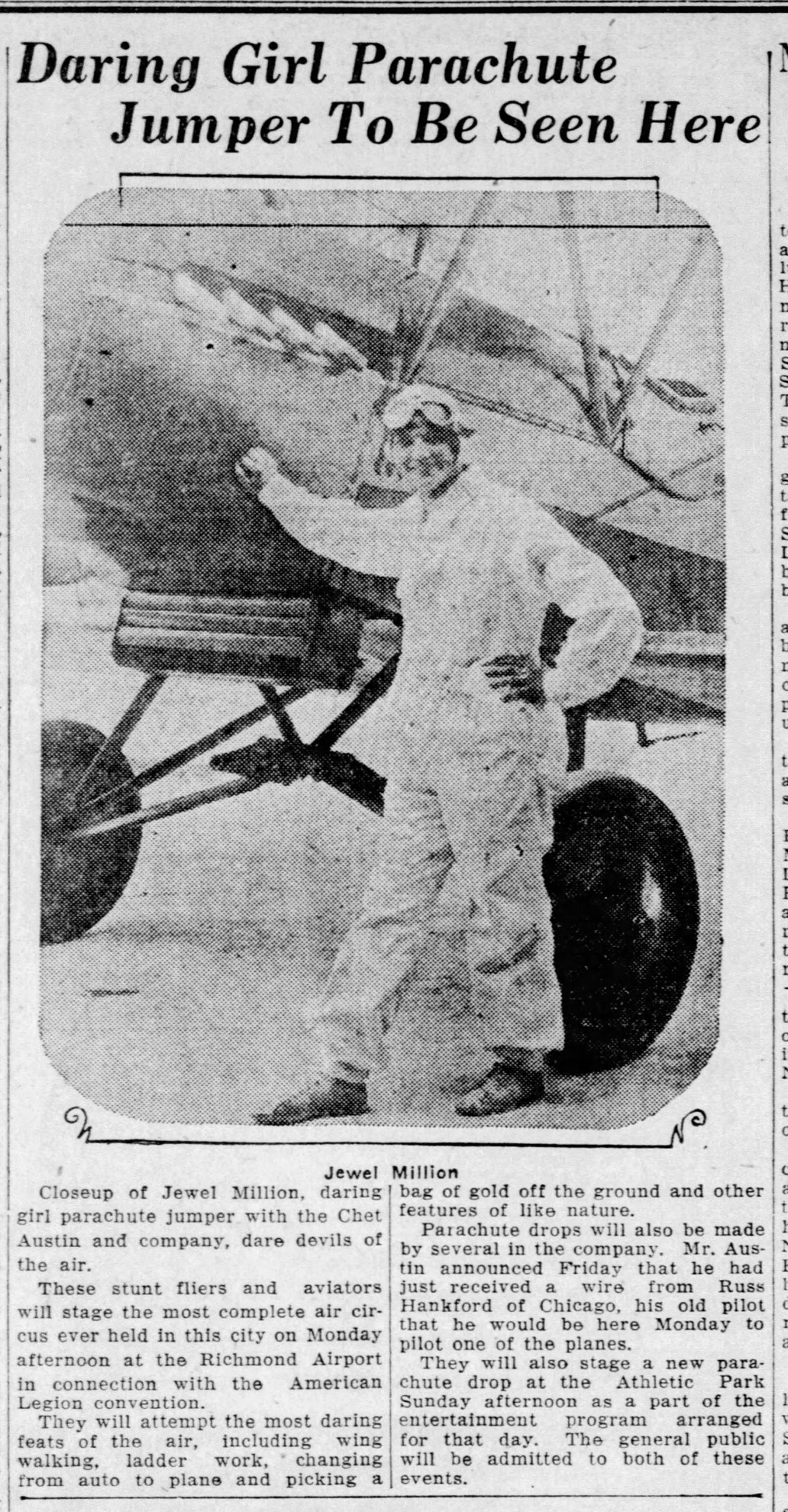

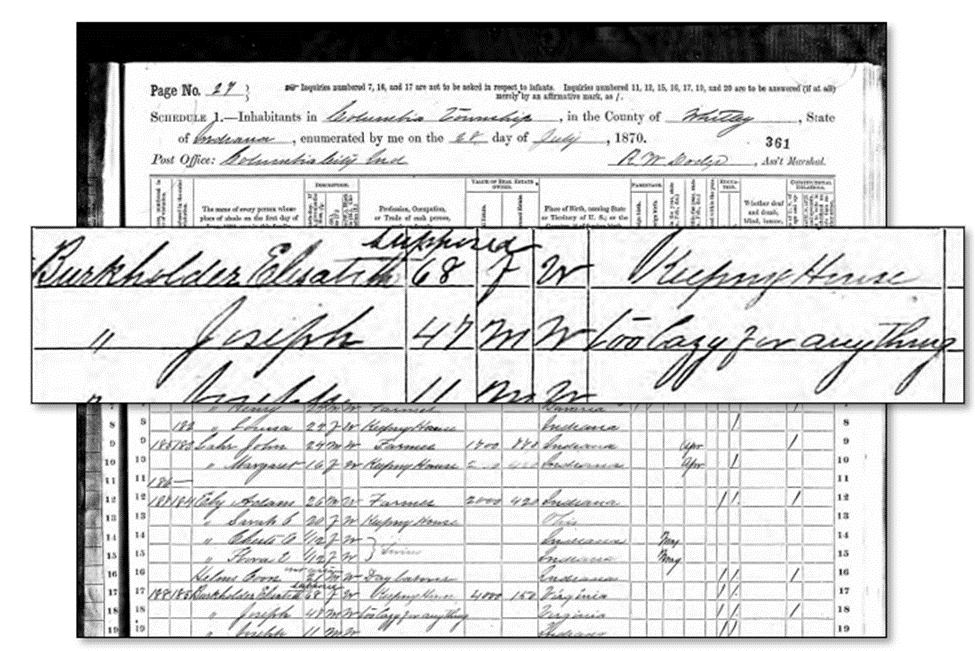

The U.S. federal census is another potential resource. For example, the 1920 census of Kosciusko County, Indiana identifies Frank Stellingworf of 52 Chapman Road as a celery farmer. While it is often overlooked, it’s rare to have a holiday meal that doesn’t include one or more dishes with celery as an ingredient. It was also commonly grown by Dutch immigrants, like Mr. Stellingworf. If you have Dutch ancestors that grew celery, you could connect to that heritage by growing it in your garden.

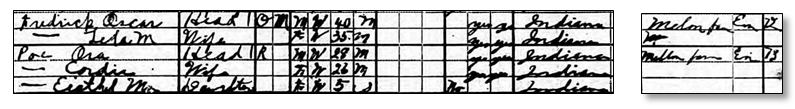

In another example, Oscar Fredrick and Ora Poe are listed on this 1920 Knox County, Indiana census as melon farmers. There are few things sweeter than fresh Indiana melon in the summertime.

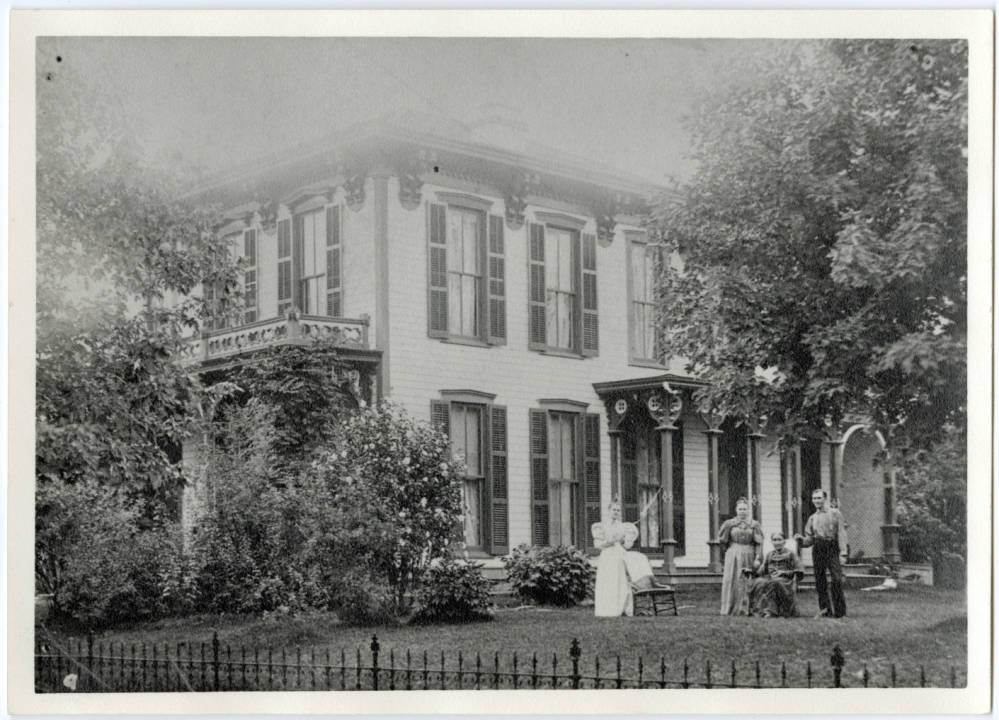

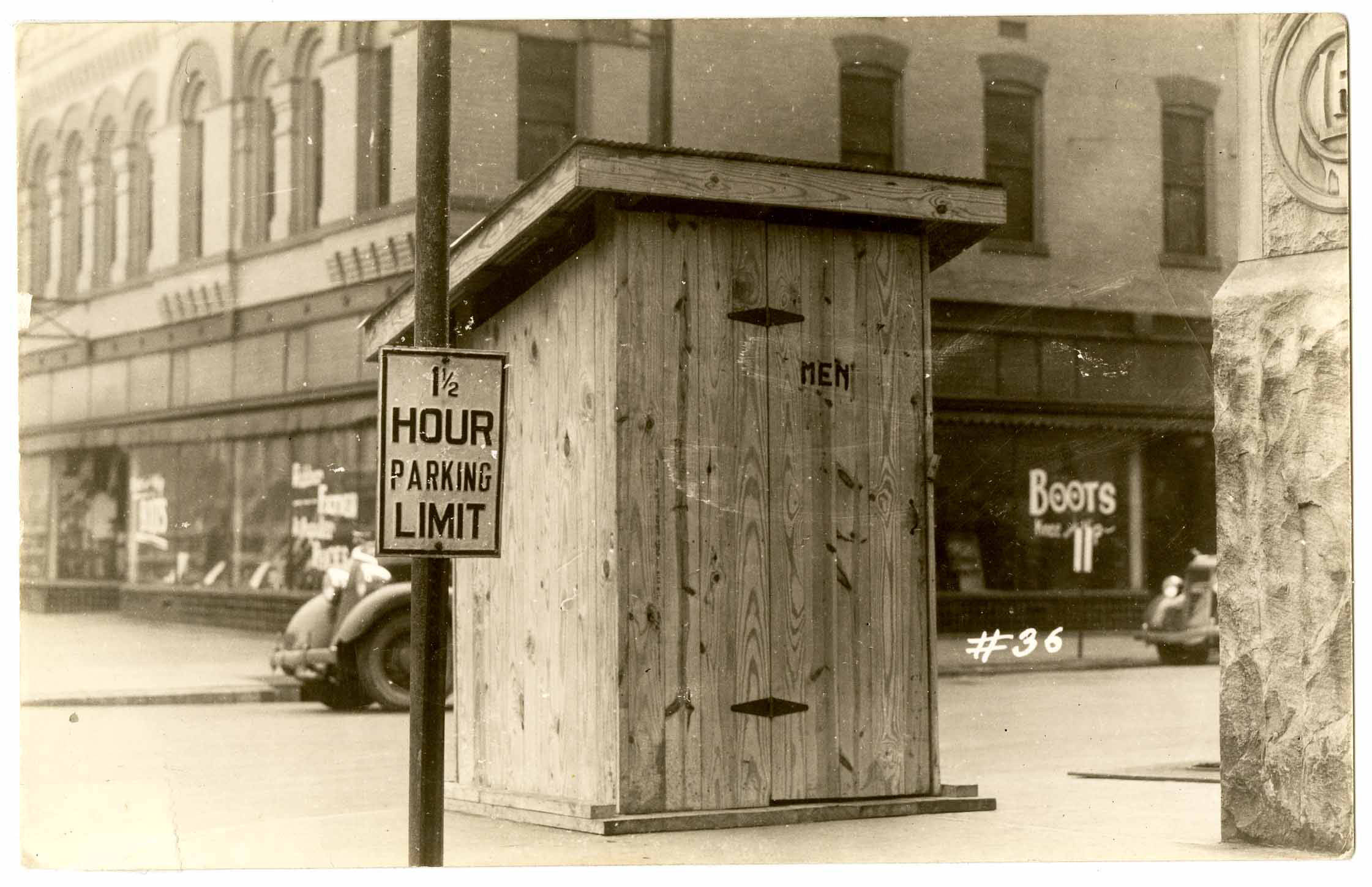

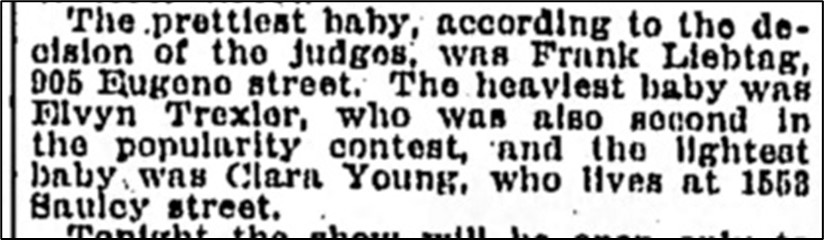

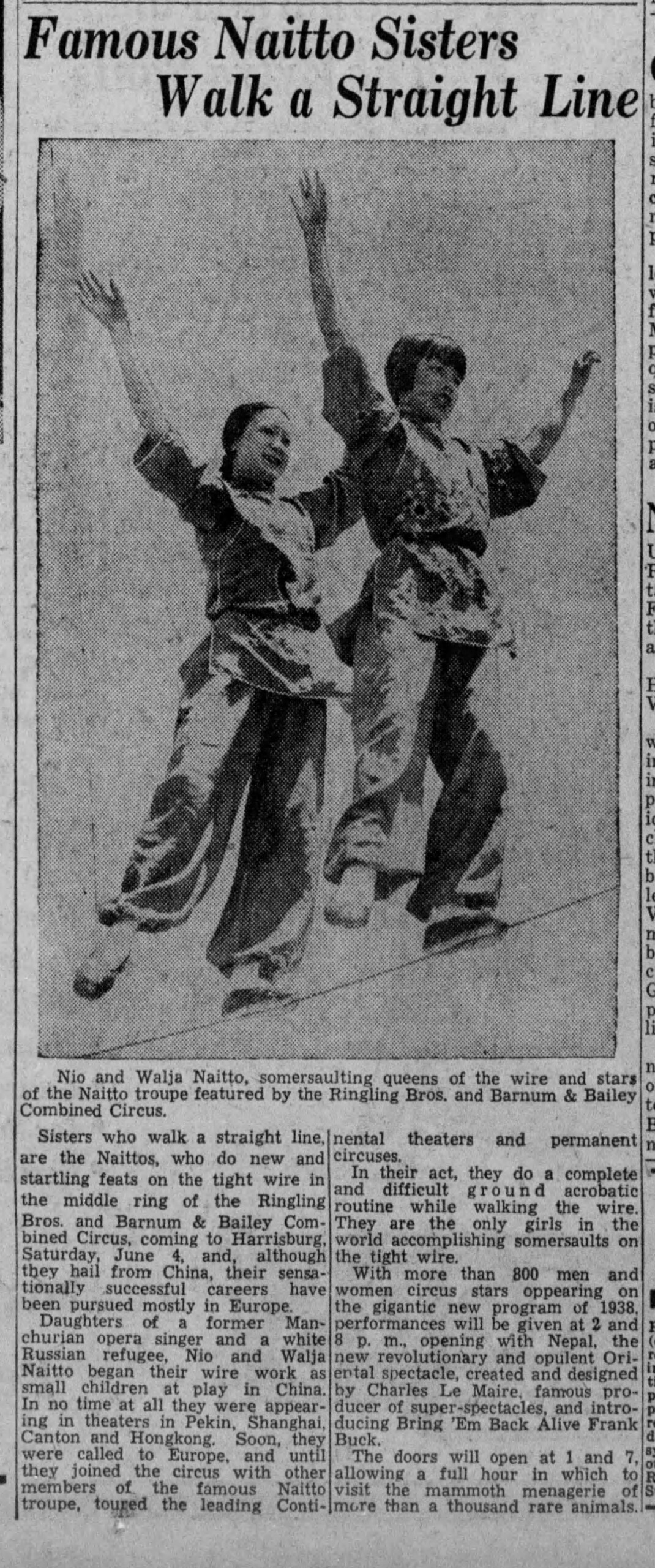

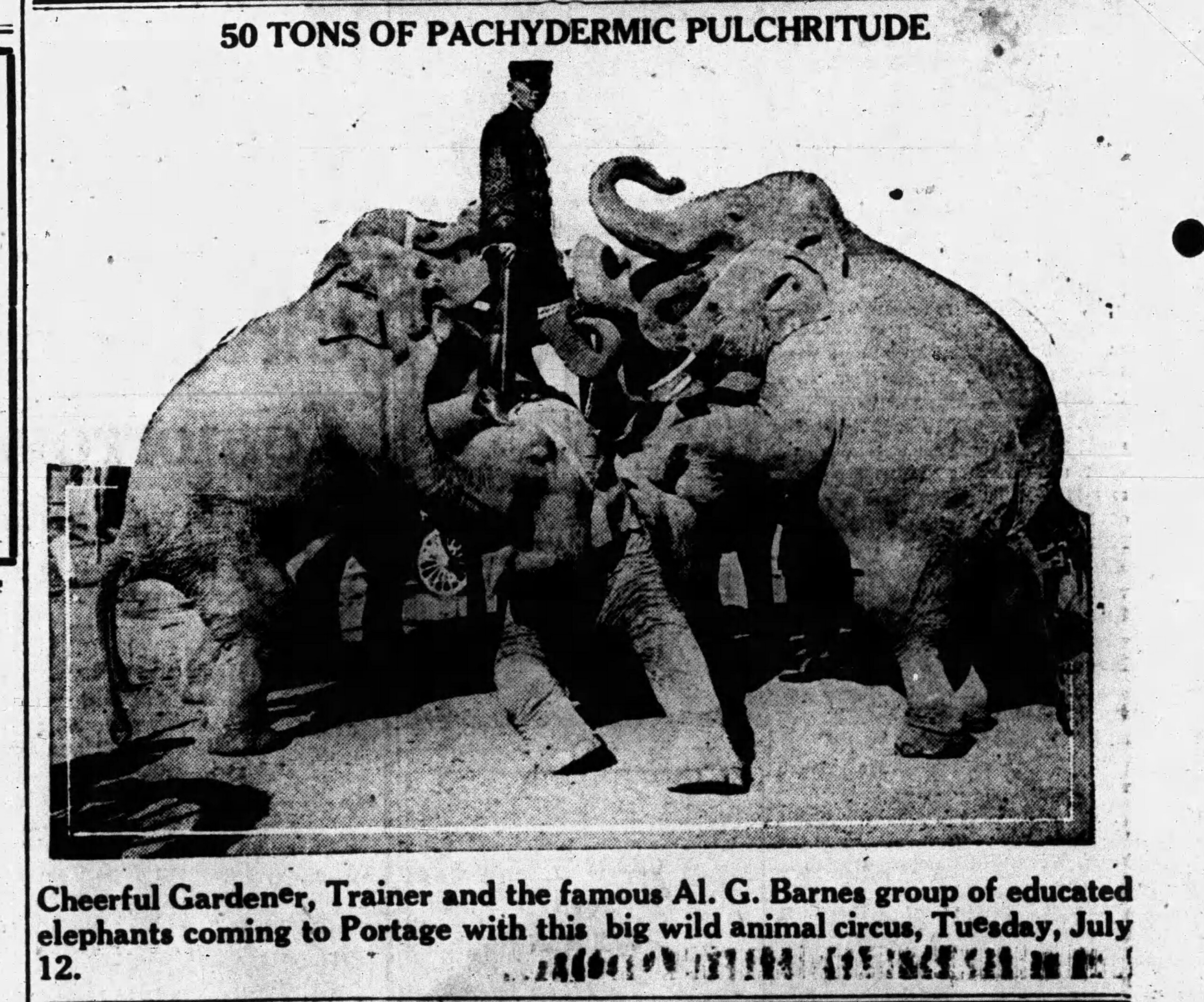

The library’s newspaper databases include news about local farms, gardeners or gardens. By searching these databases, you may learn interesting tidbits about your family, like that your relative grew the largest pumpkin, planted the sweetest strawberries or raised the fattest carrot in their town. For example, Earl Grider is shown below with an impressive ten-pound cucumber that is taller than his 3-year-old son.

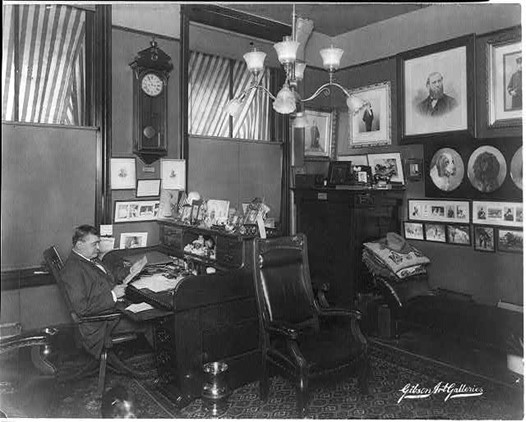

Mike Vulk, is pictured standing inside of the plot he grew on a small strip of land on Maryland St. in 1934. He didn’t allow the lack of a yard to stop him from growing carrots, beans, cabbage, and corn in his city garden.

From the June 23, 1934 Indianapolis Times:

“Trucks and automobiles whiz by Mr. Vulk’s garden daily; just across the street, workmen in a factory have watched its progress with interest. But Mr. Vulk doesn’t think it anything unusual. He eyes the green, flourishing rows of vegetables with satisfaction.

‘A fine garden!’ Mr. Vulk comments. ‘There’s many a good kettle of soup that will come out of that garden.’

And the scarecrow doesn’t answer a word.”

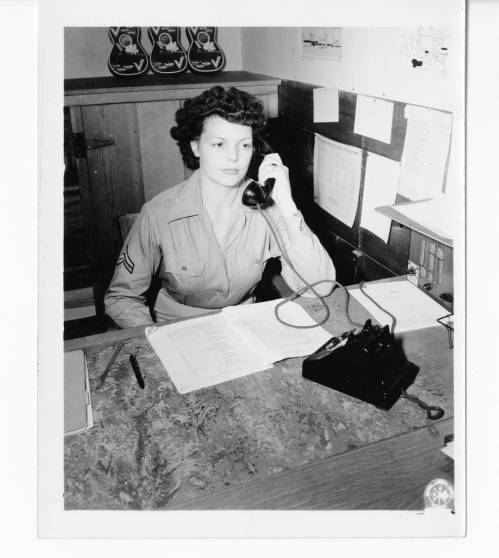

During wartime, many people planted Victory Gardens to support the effort and supplement groceries. Victory Gardens were reported on in the newspapers frequently to promote them within the community. According to this article in Evansville Courier Sun featuring a lovely Mrs. Kenneth Miller working in her Victory Garden while inexplicably wearing fine clothes and pearls, “Mrs. Miller digs into the soil which she hopes will fork over plenty of corn, beets, potatoes and what have you in the vegetable line to chase away the ration point blues.”

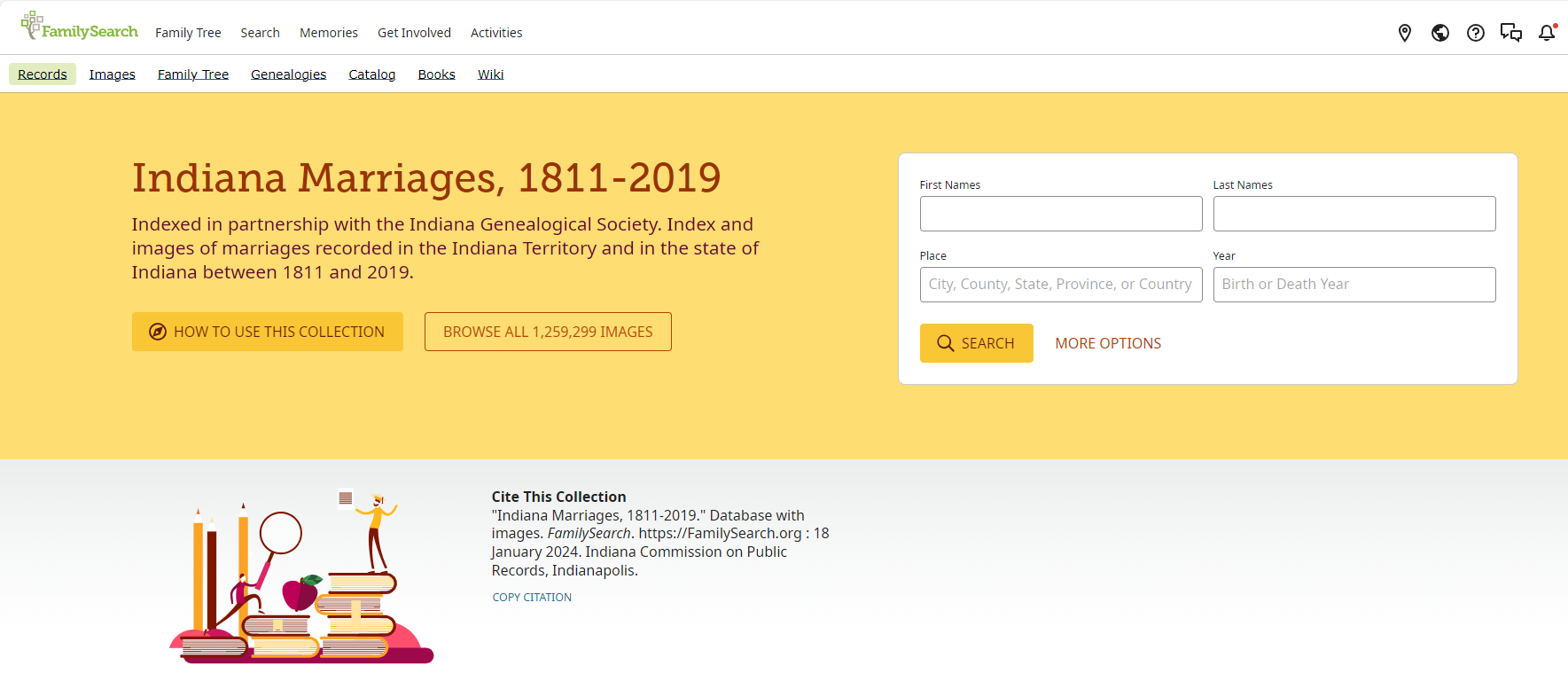

County histories often include details on early farm life and the local flora and fauna. By researching the history of the area you may discover the plants your ancestors were likely to encounter or grow. For example, “The History of Hancock County, Indiana; Its People, Industries and Institutions” by George J. Richman describes the principal crops, soil types, native plants and animals and area farms. The Indiana State Library has numerous county histories in the collection, and you may find some digitized online you can read for free on websites such as Archive.org or Familysearch.org.

There are few things more satisfying than harvesting fresh ingredients from your own garden and incorporating them into family meals. Pass those memories on to the next generation by preserving your connections to those home-grown foods. Books like, “From the Family Kitchen: Discover Your Food Heritage and Preserve Favorite Recipes” by author Gena Philibert-Ortega and “Preserving Family Recipes: How to Save and Celebrate Your Food Traditions” by Valerie J. Frey offer insights and ideas on how to share that history with your family.

Now is a perfect time to share the gift of your garden with your loved ones while connecting it to your family story.

However you choose to celebrate springtime with your family, I wish you a very happy and fruitful season!

This blog post is by Dagny Villegas, Genealogy Division librarian.