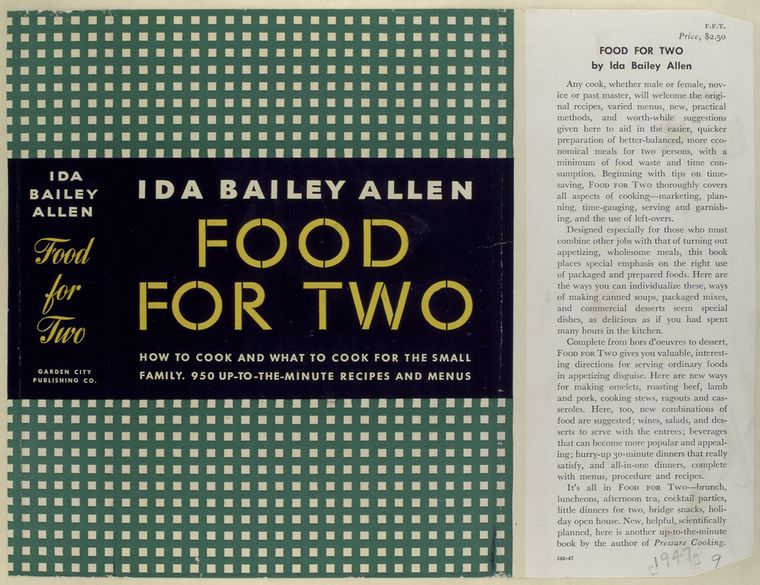

I have a cookbook that was my grandmother’s. The cookbook, “Food for Two,” was acquired during her engagement to my grandfather. I also have handwritten recipes from another grandmother. These items are among my most treasured family heirlooms.

I have memories of my grandmothers making gingerbread cake, johnny cakes in the pan – fried in lard, beef and homemade noodles. Saturday evenings I watched my great grandmother make communion bread for Sunday’s service.

I have memories of my grandmothers making gingerbread cake, johnny cakes in the pan – fried in lard, beef and homemade noodles. Saturday evenings I watched my great grandmother make communion bread for Sunday’s service.

Though my life is surrounded by living memories of sharing food and life with family, I have also wondered what my ancestors’ lives were like. What their occupations were, what their environments – the places they lived – looked like, what music they listened to and I wondered what did my ancestors eat? All the things that make a life full.

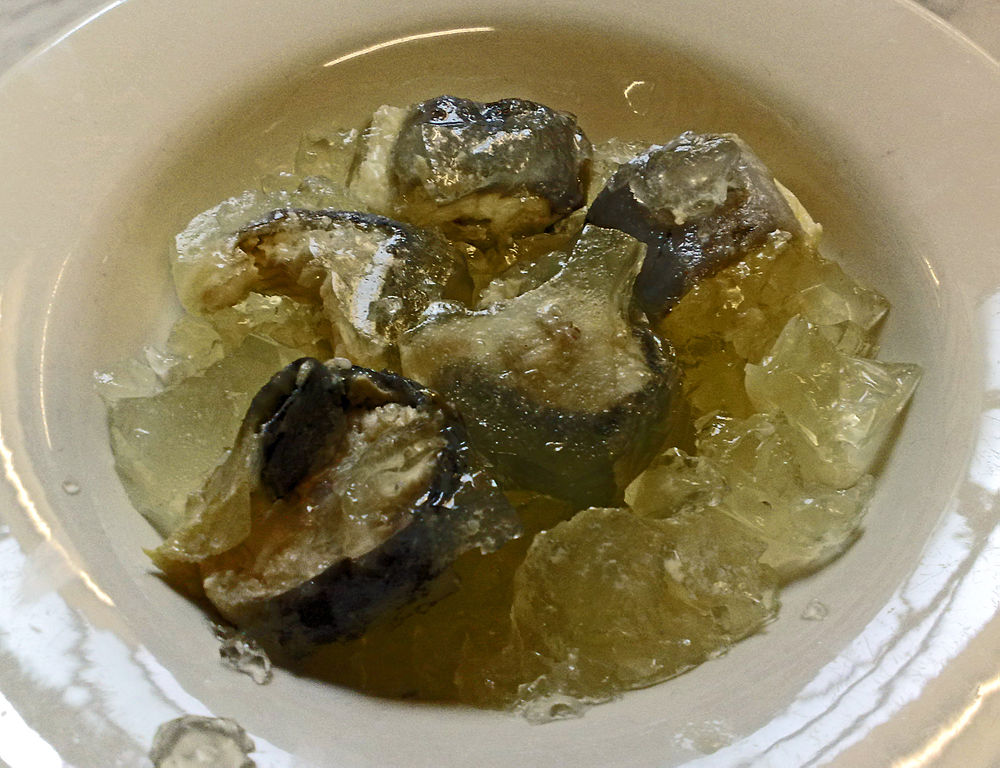

My family has no sheen of the gentry on it and some of them lived in London. My ancestors who lived in London lived near the river Thames, and the river provides. And what does it provide? Eels. Eels from the Thames river. Cooked eels, eel pies and jellied eels.

Like many Midwesterners, I have plenty of Irish heritage, too. I have wondered: What did the Irish eat?

Like many Midwesterners, I have plenty of Irish heritage, too. I have wondered: What did the Irish eat?

Even though corned beef is often associated with our Irish ancestors, it was not beef they were eating – that was for the wealthy British landowners. Potatoes – also often associated with our Irish ancestors – were brought in to feed the poor, Irish tenant farmers. Of course, when the cheap food source of potatoes failed in Ireland; many Irish migrated to America.

But when families have plenty of food, they use food to show love, celebrate, tell stories and heal.

Recently, foodways were used to bring healing to the native peoples in Minneapolis during the COVID pandemic.

Family foodways can turn into family businesses and then influence and change the surrounding culture as the Chili Queens of San Antonio did.

Food can be about survival, too. Michael W. Twitty explored his family’s experience of slavery through food.

Sometimes the recipes and the food are a clue in family history, as it was for Cuban-American, Genie Milgrom.

What will your family foodways tell you about your family history?

Books about foodways in the Indiana State Library’s collection to explore:

“Dellinger family : American history and cookbook,” ISLG 929.2 D357M

“Keaton Mills family cemetery, Egeria: an era: family stories and cookbook,” ISLG 929.2 M657MA

“Weesner family favorites: a recollection of old and new recipes,” ISLG 929.2 W3983R

“The cooking gene: A Journey Through African American Culinary History in the Old South Twitty,” Michael W., available as an e-book

“Historical Indiana cookbook,” ISLI 641.5 K72H

“Farm fixin’s: food, fare & folklore from the pioneer village,” ISLI 641.5 F233

“Aspic and old lace: ten decades of cooking, fashion, and social history,” ISLI 641.5 B295

“Pennsylvania Dutch cookbook of fine old recipes: compiled from tried and tested recipes made famous and handed down by the early Dutch settlers in Pennsylvania,” ISLM TX721 .P46 1971

“Quaker cooking and quotes,” ISLI 641.5 B655q

“Cooking from quilt country: hearty recipes from Amish and Mennonite kitchens,” ISLI 641.5 A215C

“The Catholic cookbook; traditional feast and fast day recipes,” ISLM 641.5 K21C

“Consuming passions being an historic inquiry into certain English appetites,” ISLM TX645 .P84 1971

“Rappite cookbook,” ISLO 641.5 no. 29

Online Sources about foodways to explore:

Jellied Eels

What the Irish Ate Before Potatoes

Is Corned Beef Really Irish?

Medieval Cookery

The Sifter A Tool For Food History Research

Historic Cookbooks on line

Generations of Handwritten Mexican Cookbooks Are Now Online

Mexican Cookbook Collection

Recetas: Cooking in the Time of Coronavirus

This blog post is by Angi Porter, Genealogy Division librarian.