Today we welcome guest blogger Jenny Kobiela-Mondor, assistant director at the Eckhart Public Library.

I’ve worked at Eckhart Public Library for almost seven years, and for more than a third of that time, our library has been coping, in one way or another, with really tough situations.

I’ve worked at Eckhart Public Library for almost seven years, and for more than a third of that time, our library has been coping, in one way or another, with really tough situations.

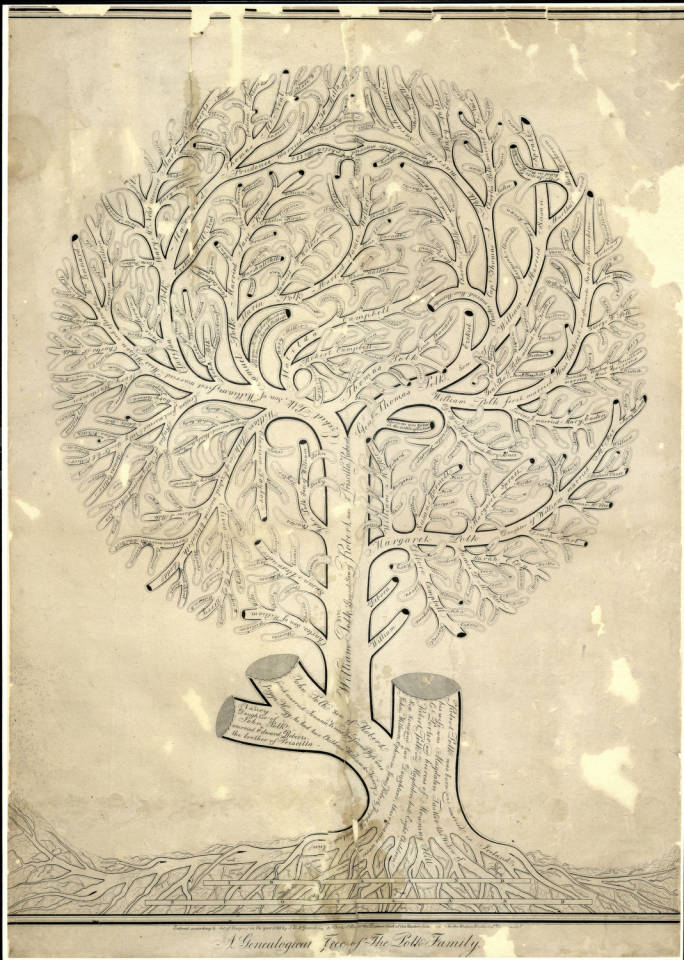

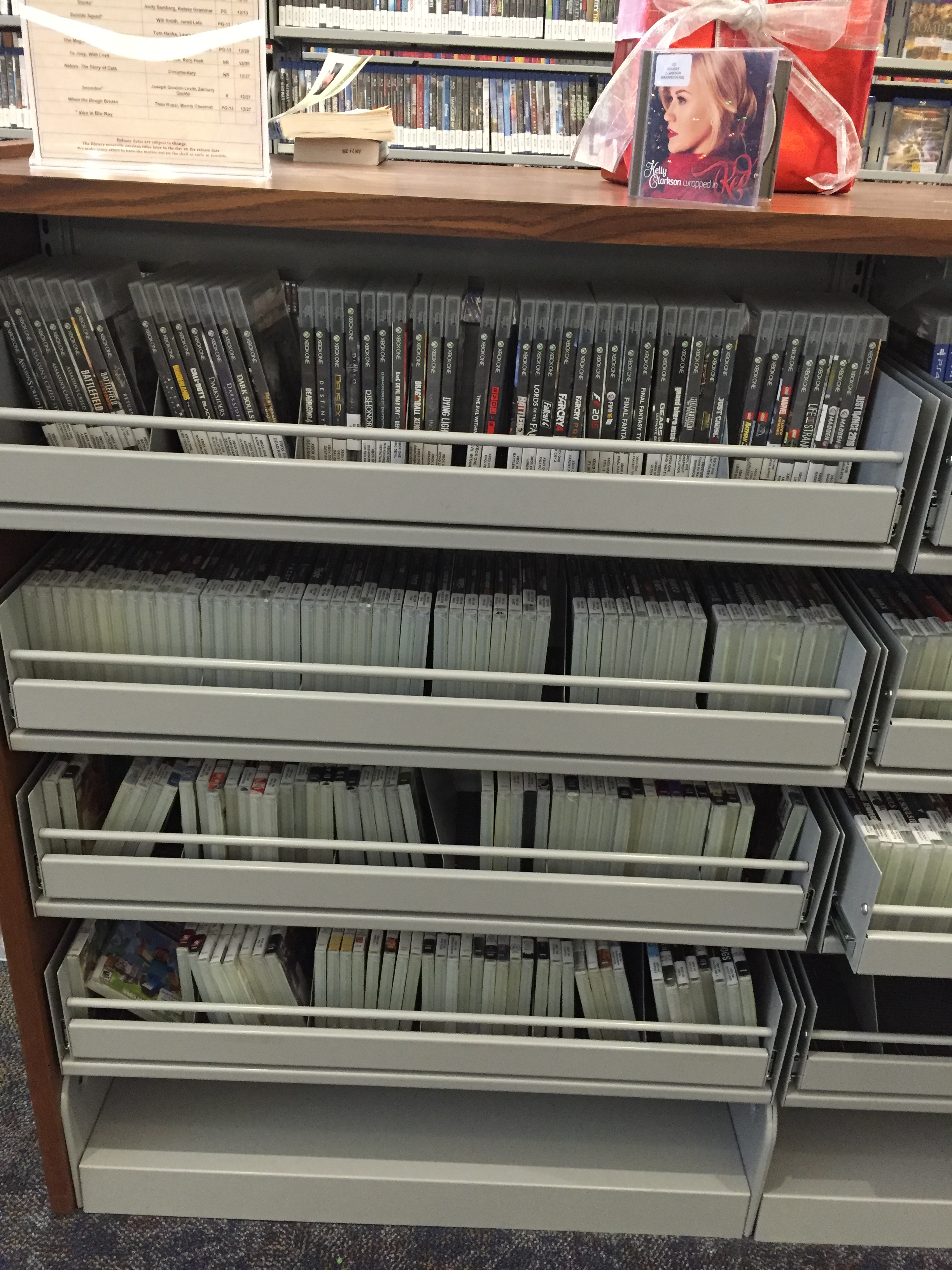

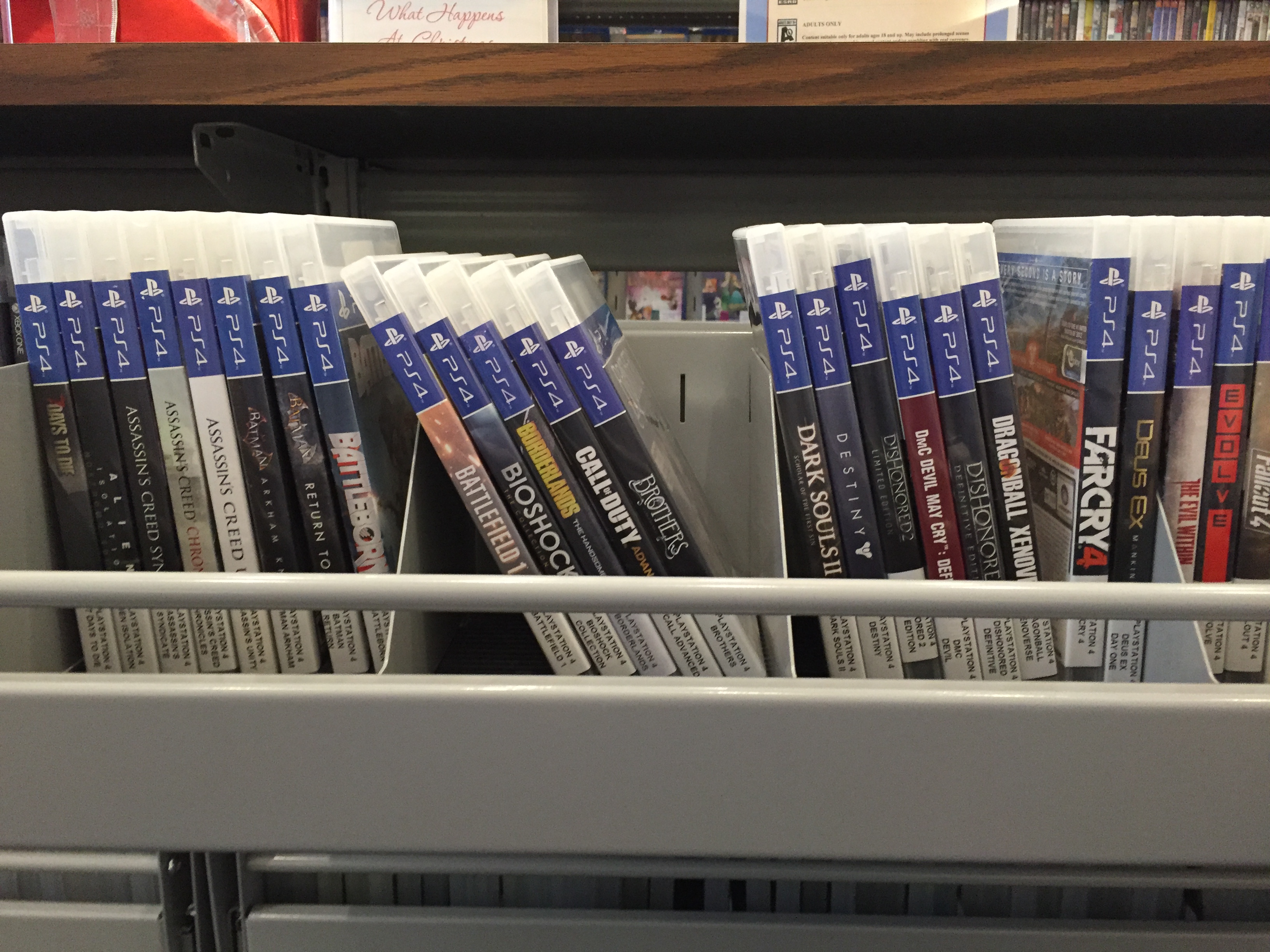

Early in the morning on July 2, 2017, someone threw a large mortar-style firework in the book drop connected to our Main Library building, starting a fire that destroyed the interior of the building, including every single book and DVD we had there, artwork, furniture, computers and more. We spent 987 days with our Main Library building closed, operating out of our Teen Library and Genealogy Center buildings, as well as a storefront we rented. On March 15, we reopened the Main Library to the public, and were opened for service for a whopping 12 hours before we closed due to COVID-19.

To say that the past 1,000 days have been tough is an understatement. However, during these difficult years, I’ve learned some great techniques for coping – and even thriving – through tough times!

Slow down, you move too fast

The instinct when an emergency happens is to act. And, it’s true – there will be urgent matters. For example, only a few hours after our incredible firefighters had put out the fire, our director, Janelle Graber, went in and grabbed important financial documents from her office. When we decided to close for the COVID-19 pandemic, we had to notify staff and patrons as soon as possible. But once a situation has been stabilized, put the slow clock on and try to be as calm and methodical as possible in your response. Take time to sit down and make a plan. It will feel wrong, because you will absolutely want to do something tangible to try to make the situation better, but it’s not helpful to rush around without a plan, or with only a vague plan.

Throw a pity party!

When times are tough, some of us try to put on a brave face. It’s important, particularly if you’re in a leadership role, not to seem like you’re losing it when something bad happens, but it’s also vital to feel your feelings of grief, anger, fear or whatever else you’re feeling. One of my favorite techniques for working through those feelings is one that my mom has used over the years, particularly when she’s had tough medical issues such as cancer – I throw myself a pity party! When I start to feel like I want to cry, or rant, or pout – or all three at once – I look at the clock and give myself 15 minutes to do just that. It’s very cathartic to give yourself permission to feel whatever you’re feeling, and it’s helpful to have a time limit to avoid getting into an unhelpful cycle of grief or anger. If you’re in a leadership position, make sure your staff also has access to the tools to help work through their feelings – whether that’s bringing in someone who specializes in grief, someone to lead a meditation or relaxation session or just a sympathetic ear. That was something we missed in the immediate aftermath of the fire, and it made it harder for all of us to move forward.

Flex your flexibility muscles

Being flexible is absolutely essential when dealing with an emergency or a tough situation. Making plans is very important, of course, but those plans must be able to change when the situation warrants it. Especially in an emergency situation, flexibility will get you far. As we got ready for our reopening and realized how the COVID-19 pandemic would affect it, we had to scale back our celebration, figure out how to protect the staff and patrons, and prepare for the possibility of closing the library completely. Everybody needs to be poised to be ready to react to changing situations.

Communication is key

Honestly, communication is always key in an organization, but there’s no time that it’s more important than in a difficult situation. Our management team struggled with wanting to have solid answers after the fire, and sometimes that caused us to wait until all of the pieces were in place before we told the rest of the library team what was going on. However, in such a scary situation, some information is better than no information. Members of your team don’t necessarily need every detail, nor do they need a constant trickle of information, but updates, even updates that are simply, “We’re not sure what the next step is, but we’re working on it,” are soothing. Remember, too, that communication is a two-way street. Library leadership need to listen to what staff are saying, and try not to get defensive if staff are confused or upset. Sometimes they just need to know that a leader in your organization knows what’s going on. And if you’re not part of that decision-making process, have patience for the people who are. Remember that everybody, at all levels of the organization, is stressed out and trying to figure out what to do.

Call in the cavalry!

No matter how amazing your library is, you can’t do this alone. And don’t feel like you need to! Call on your partners, volunteers and advocates to help out! After the fire, we needed places to meet and to hold programming. Our Community Foundation building became a home-away-from-home, particularly for meetings during those early days. Our grand finale of our Summer Reading Program was two weeks after the fire, and we were able to switch it to a local park, borrow lawn games from other libraries and have partner organizations bring games and activities. Talk to your supporters about what they can do for you, and what they can do to boost morale at your library. Even something as simple as a batch of chocolate chip cookies from a friends group member or $5 gift cards to your local coffee shop for staff can go a long way to making things look brighter in a dark time.

Take a break

During a tough time, your coworkers and patrons need you for the long haul. That means that your mental and physical health is extremely important. It can be hard for those of us who are passionate about our libraries to take a vacation, or sometimes even just a lunch break, in the midst of a difficult situation, but burnout is real and exhaustion can make you sick – and that doesn’t help your organization, your coworkers or your patrons! Everybody needs time to recharge, so don’t be afraid to take the time that you need. You’ll end up being more productive and better able to deal with challenges when you’re well-rested and healthy.

Always look on the bright side of life!

Our biggest challenges can sometimes also lead to unexpected wins. After our fire, we were able to sit down and really consider what our patrons need from a 21st century library. We had been starting to work on weeding, and suddenly we were able to work on building an incredible collection. Even the COVID-19 pandemic has allowed us to expand virtual programming, work on professional development, and bring more attention to our digital collection. You don’t have to be relentlessly positive – again, it’s good to spend some time grieving or worrying – but there are silver linings to nearly every difficult situation.

And finally …

Hang in there! This is an incredible and unprecedented challenge, but Indiana libraries – and libraries all over the country – are doing an amazing job responding! You’ve got this!

This post was written by Jenny Kobiela-Mondor, assistant Director at the Eckhart Public Library.